Polio was almost eradicated. This year it staged a comeback

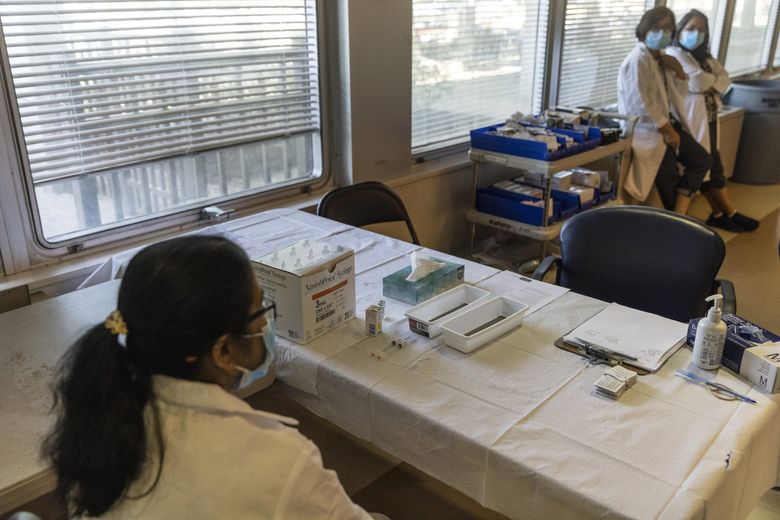

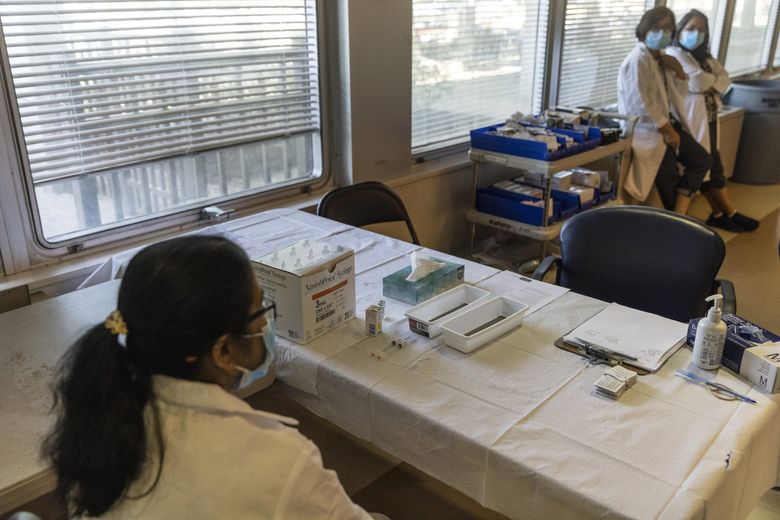

A pop-up polio vaccination site set up by county health department in Pomona, New York, July 22. Public health officials had a simple message on Monday for parents concerned by the discovery of poliovirus in New York City... (Victor J. Blue / The New York Times)More

By Apoorva Mandavilli

The New York Times

Aug. 19, 2022

At the beginning of this year, there was a thrum of excitement among global health experts: Eradication of polio, a centuries-old foe that has paralyzed legions of children around the globe, seemed tantalizingly close.

Pakistan, one of only two countries where wild poliovirus still circulates, had not recorded cases in more than a year. Afghanistan had reported only four.

But eradication is an uncompromising goal. The virus must disappear from every part of the world and stay gone, regardless of wars, political disinterest, funding gaps or conspiracy theories. New signs of the virus in a single country can derail the effort.

In polio’s case, there were several ominous setbacks.

Malawi in February announced its first case in 30 years, a 3-year-old girl who became paralyzed after infection with a virus that appeared to be from Pakistan. Pakistan itself went on to report 14 cases, eight of them in a single month last spring.

In March, Israel reported its first case since 1988. Then, in June, British authorities declared an “incident of national concern” when they discovered the virus in sewage. By the time New York City detected the virus in wastewater last week, polio eradication seemed as elusive as ever.

“It’s a poignant and stark reminder that polio-free countries are not really polio-risk free,” said Dr. Ananda Bandyopadhyay, deputy director for polio at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the largest supporter of polio eradication efforts.

The virus is always “a plane ride away,” he added.

Polio is a highly contagious and sometimes deadly enemy, capable of ravaging the nervous system and causing paralysis within hours. Those who recover could relapse and become seriously ill years later.

The virus multiplies in the intestine for weeks and could spread through feces or contaminated food or water — for example, when an infected child uses the toilet, neglects washing hands and then touches food.

For decades, the virus terrorized families, causing paralysis among more than 15,000 American children each year and hundreds of thousands more worldwide. Its retreat is a triumph of vaccination. After the first vaccine arrived in 1955, the number of cases dropped precipitously, and by 1979, the United States was declared polio-free.

Although the United States and Britain have high immunization rates, they also have pockets of low immunity that allow the virus to flourish. In those communities, all unvaccinated people — not just children — are at risk. If polio continues to spread in the United States for a year, the country may lose its polio-free status under World Health Organization guidelines.

Aid organizations first aspired to eradicate polio in 1988 and poured billions of dollars into the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, a consortium of six partners, including the Gates Foundation, WHO, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Despite the recent cases, the progress is unmistakable: Global cases of polio have fallen by 99% — from 350,000 cases of paralysis in 1988 to about 240 so far this year.

That success “is both a miraculous thing and a thing that’s taken way, way longer than people expected,” Bill Gates, who has taken a pointed interest in polio, said in an interview in February. “Eradications are super hard, and they rarely should be undertaken.”

Ending polio has been particularly challenging.

There are three strains of the wild poliovirus. Type 2 was declared eradicated in 2015, and Type 3 in 2019. Only Type 1 poliovirus remains at large, and only in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Immunization for polio can be done in one of two ways. The injected vaccine used in the United States and most rich countries contains killed virus, is powerfully protective against illness but doesn’t prevent the vaccinated from spreading the virus to others.

Mass vaccination campaigns rely on the oral polio vaccine, which delivers weakened virus in just a few drops on the tongue. The oral vaccine is inexpensive, easy to administer and can prevent infected people from spreading the virus to others, a method better suited to extinguishing outbreaks.

But it has one paradoxical flaw: Vaccinated children can shed the weakened virus in feces, and from there, it can sometimes find its way back into people, occasionally setting off a chain of infections in communities with low immunization rates.

If the weakened virus circulates for long enough, it can slowly mutate back into a more virulent form that can cause paralysis.

Even as wild poliovirus has been on the decline, so-called vaccine-derived polio has been on the upswing. Cases tripled between 2018 and 2019, and again between 2019 and 2020. Between January 2020 and this past April, 33 countries reported a total of nearly 1,900 cases of paralysis from vaccine-derived polio.

The samples found in London sewage, in Israel and in New York are all vaccine-derived virus. They carry the same genetic fingerprint, suggesting that the virus may have been circulating undetected for about a year somewhere in the world.

Eradicating polio would require wiping out the vaccine-derived type, not just the few remaining hot spots of wild virus. “We definitely need to stop all polio transmission, whether wild poliovirus or whether circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus,” said John Vertefeuille, who heads polio eradication at the CDC.

Vaccine-derived polio has become more prevalent because the oral vaccine in use now protects against only Types 1 and 3 of the virus. In 2016, buoyed by the seeming eradication of Type 2 virus, the WHO withdrew it from the oral vaccine. That move left the world increasingly vulnerable to outbreaks of residual Type 2 virus.

At the same time, global health organizations shifted away from maintaining nimble teams that can swiftly stamp out outbreaks to strengthening health care systems overall. Regions that struggle to contain polio tend to have other public health problems, such as poor nutrition, poor access to safe drinking water and other infectious disease outbreaks.

But the response to an outbreak of polio — or to other infectious diseases such as COVID-19 or monkeypox — requires dedicated teams and programs, said Kimberly Thompson, a health care economist whose work focuses on polio eradication.

The WHO has not delivered on that goal for decades, “but there is no accountability for performance,” Thompson said. Likewise, countries that receive funding for polio are rarely held responsible for diverting the money to other programs, she added.

As a result of the dismantling of outbreak teams, the response to vaccine-derived polio has often been sluggish and inefficient.

“The speed and the quality of the responses will have to go up in order for us to stop these outbreaks,” Vertefeuille said.

A pop-up polio vaccination site set up by county health department in Pomona, New York, July 22. Public health officials had a simple message on Monday for parents concerned by the discovery of poliovirus in New York City... (Victor J. Blue / The New York Times)More

By Apoorva Mandavilli

The New York Times

Aug. 19, 2022

At the beginning of this year, there was a thrum of excitement among global health experts: Eradication of polio, a centuries-old foe that has paralyzed legions of children around the globe, seemed tantalizingly close.

Pakistan, one of only two countries where wild poliovirus still circulates, had not recorded cases in more than a year. Afghanistan had reported only four.

But eradication is an uncompromising goal. The virus must disappear from every part of the world and stay gone, regardless of wars, political disinterest, funding gaps or conspiracy theories. New signs of the virus in a single country can derail the effort.

In polio’s case, there were several ominous setbacks.

Malawi in February announced its first case in 30 years, a 3-year-old girl who became paralyzed after infection with a virus that appeared to be from Pakistan. Pakistan itself went on to report 14 cases, eight of them in a single month last spring.

In March, Israel reported its first case since 1988. Then, in June, British authorities declared an “incident of national concern” when they discovered the virus in sewage. By the time New York City detected the virus in wastewater last week, polio eradication seemed as elusive as ever.

“It’s a poignant and stark reminder that polio-free countries are not really polio-risk free,” said Dr. Ananda Bandyopadhyay, deputy director for polio at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the largest supporter of polio eradication efforts.

The virus is always “a plane ride away,” he added.

Polio is a highly contagious and sometimes deadly enemy, capable of ravaging the nervous system and causing paralysis within hours. Those who recover could relapse and become seriously ill years later.

The virus multiplies in the intestine for weeks and could spread through feces or contaminated food or water — for example, when an infected child uses the toilet, neglects washing hands and then touches food.

For decades, the virus terrorized families, causing paralysis among more than 15,000 American children each year and hundreds of thousands more worldwide. Its retreat is a triumph of vaccination. After the first vaccine arrived in 1955, the number of cases dropped precipitously, and by 1979, the United States was declared polio-free.

Although the United States and Britain have high immunization rates, they also have pockets of low immunity that allow the virus to flourish. In those communities, all unvaccinated people — not just children — are at risk. If polio continues to spread in the United States for a year, the country may lose its polio-free status under World Health Organization guidelines.

Aid organizations first aspired to eradicate polio in 1988 and poured billions of dollars into the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, a consortium of six partners, including the Gates Foundation, WHO, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Despite the recent cases, the progress is unmistakable: Global cases of polio have fallen by 99% — from 350,000 cases of paralysis in 1988 to about 240 so far this year.

That success “is both a miraculous thing and a thing that’s taken way, way longer than people expected,” Bill Gates, who has taken a pointed interest in polio, said in an interview in February. “Eradications are super hard, and they rarely should be undertaken.”

Ending polio has been particularly challenging.

There are three strains of the wild poliovirus. Type 2 was declared eradicated in 2015, and Type 3 in 2019. Only Type 1 poliovirus remains at large, and only in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Immunization for polio can be done in one of two ways. The injected vaccine used in the United States and most rich countries contains killed virus, is powerfully protective against illness but doesn’t prevent the vaccinated from spreading the virus to others.

Mass vaccination campaigns rely on the oral polio vaccine, which delivers weakened virus in just a few drops on the tongue. The oral vaccine is inexpensive, easy to administer and can prevent infected people from spreading the virus to others, a method better suited to extinguishing outbreaks.

But it has one paradoxical flaw: Vaccinated children can shed the weakened virus in feces, and from there, it can sometimes find its way back into people, occasionally setting off a chain of infections in communities with low immunization rates.

If the weakened virus circulates for long enough, it can slowly mutate back into a more virulent form that can cause paralysis.

Even as wild poliovirus has been on the decline, so-called vaccine-derived polio has been on the upswing. Cases tripled between 2018 and 2019, and again between 2019 and 2020. Between January 2020 and this past April, 33 countries reported a total of nearly 1,900 cases of paralysis from vaccine-derived polio.

The samples found in London sewage, in Israel and in New York are all vaccine-derived virus. They carry the same genetic fingerprint, suggesting that the virus may have been circulating undetected for about a year somewhere in the world.

Eradicating polio would require wiping out the vaccine-derived type, not just the few remaining hot spots of wild virus. “We definitely need to stop all polio transmission, whether wild poliovirus or whether circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus,” said John Vertefeuille, who heads polio eradication at the CDC.

Vaccine-derived polio has become more prevalent because the oral vaccine in use now protects against only Types 1 and 3 of the virus. In 2016, buoyed by the seeming eradication of Type 2 virus, the WHO withdrew it from the oral vaccine. That move left the world increasingly vulnerable to outbreaks of residual Type 2 virus.

At the same time, global health organizations shifted away from maintaining nimble teams that can swiftly stamp out outbreaks to strengthening health care systems overall. Regions that struggle to contain polio tend to have other public health problems, such as poor nutrition, poor access to safe drinking water and other infectious disease outbreaks.

But the response to an outbreak of polio — or to other infectious diseases such as COVID-19 or monkeypox — requires dedicated teams and programs, said Kimberly Thompson, a health care economist whose work focuses on polio eradication.

The WHO has not delivered on that goal for decades, “but there is no accountability for performance,” Thompson said. Likewise, countries that receive funding for polio are rarely held responsible for diverting the money to other programs, she added.

As a result of the dismantling of outbreak teams, the response to vaccine-derived polio has often been sluggish and inefficient.

“The speed and the quality of the responses will have to go up in order for us to stop these outbreaks,” Vertefeuille said.

No comments:

Post a Comment