Colombia’s Oil Industry Faces an Existential Crisis

- Colombia’s proven oil reserves have fallen by over 400 million barrels since 2013, leaving fewer than eight years of production at current rates.

- President Petro’s bans on fracking and new exploration, combined with heavy taxation, have driven away foreign investment and weakened output.

- Without new discoveries or major policy shifts, Colombia risks losing its top export revenue source and destabilizing its economy within the decade.

A lack of oil discoveries is causing Colombia’s economically crucial petroleum reserves and production to deteriorate, sparking speculation that the industry is trapped in a death spiral. President Gustavo Petro’s bid to reduce dependence on fossil fuels by banning oil exploration and hydraulic fracturing is only accelerating the industry’s demise. This is severely impacting government income, exports, and the economy at a time when Bogota is particularly exposed to financial and geopolitical risks. Time is fast running out for Colombia to find more oil reserves while creating an economically sustainable plan to reduce dependence on hydrocarbons.

After peaking at just over 2.4 billion barrels in 2013, the highest level since 1998, Colombia’s proven oil reserves have fallen sharply since then. For 2024, those reserves were calculated to total just over two billion barrels with a relatively short production life of 7.2 years.

Source: Colombia National Hydrocarbon Agency (ANH).

This marks a steep reduction of more than 400 million barrels since 2013, reflecting Colombia's limited exploration success. You see, over the last twenty years, major oil discoveries have been rare, with only two significant finds exceeding 200 million barrels during that period. The risks this poses to Colombia’s oil-dependent economy are exacerbated by the short production life of the country’s proven reserves, with them poised to run out in less than a decade if no new major discoveries are made.

These developments underscore the considerable risks facing Colombia’s hydrocarbon-dependent economy, especially with petroleum being the country’s top export, earning $15 billion during 2024 and generating roughly a tenth of fiscal revenue. Time is running out for Colombia to make the multiple major oil and natural gas discoveries needed to boost reserves and bolster declining fiscal revenues. Although there is significant optimism regarding Colombia’s hydrocarbon potential, the country has experienced limited significant oil discoveries over the past 25 years, which poses ongoing challenges for increasing reserves.

Colombia has not seen any world-class 500 million barrel-plus oil discoveries since the early 1990s. The last was Occidental Petroleum’s 1983 discovery of the 1.1-billion-barrel Caño Limón oilfield. This is the strife-torn nation’s largest ever oil discovery, not only leading to hydrocarbon self-sufficiency but triggering a massive petroleum boom that became what is known as Colombia’s golden age of oil that lasted into the late 1990s. The Andean country’s last world-class discoveries were the 750-million-barrel Cusiana and 510-million-barrel Cupiagua oilfields found by BP in the Orinoquía foothills in 1989 and 1993, respectively.

There has been a dearth of world-class finds ever since. All crude oil discoveries have failed to break the 100-million-barrel mark, with only two exceeding 200 million barrels of recoverable oil resources. These are the 250-million-barrel Akacia and 250-million-barrel Lorito heavy oil discoveries made by Ecopetrol in its 100% owned and operated CPO-09 Block during 2010 and 2018, respectively. The CPO-09 Block, where Ecopetrol acquired the remaining 45% from Spanish energy company Repsol in February 2025 for $452 million, is believed to contain over two billion barrels of crude oil. Although questions linger over whether it is commercially exploitable.

President Petro’s attempts to reduce Colombia’s dependence on petroleum and hike taxes for extractive industries are responsible for falling energy investment. On taking office in August 2022, Petro banned hydraulic fracturing, known as fracking, and ceased awarding new oil exploration contracts. Those policy decisions are among the key reasons for Colombia’s inability to bolster proven oil reserves and declining production, with drillers slashing spending on their operations in the strife-torn country. Indeed, the lack of exploration success over the last 20 years sparked considerable speculation that the future of Colombia’s oil patch rested with fracking.

There are several geological bodies in the Andean country, notably the Cretaceous La Luna formation, a carbonaceous-bituminous limestone and calcareous shale rich in organic matter, which possesses considerable unconventional oil potential. This formation was targeted by Ecopetrol and partner ExxonMobil with the Kale and Platero fracking pilots near the municipality of Puerto Wilches in the Middle Magdalena Valley. Both operations were hugely controversial, with local communities opposed to the projects over fears of environmental damage. It was Petro’s fracking ban that caused those pilots to be scrapped and Exxon to exit Colombia.

Those regulatory changes were followed by tax hikes for extractive industries, including the economically vital oil industry. During November 2022, Petro imposed a levy on oil sales when the international Brent price hit specific thresholds, with oil companies paying an additional 5% tax when prices are $67.30 to $75 per barrel. The levy rises to 10% when prices fall between $75 and $82.20 per barrel and climbs to 15% if the price rises further. In February 2025, Bogota imposed a 1% surcharge on crude oil exports, which was extended beyond the initial 90 days to be in place for a year, with plans to make it permanent, adding to the immense tax burden weighing on oil companies.

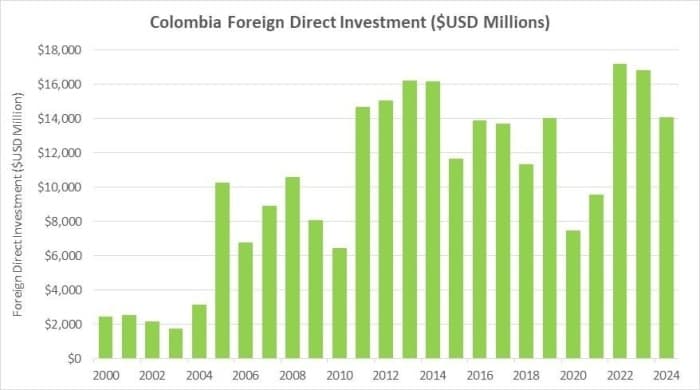

As a result, many foreign oil companies, including Big Oil, have downsized their operations in Colombia, or, like Exxon, chose to exit altogether. This is responsible for a sharp decline in foreign direct investment (FDI). According to central bank data, foreign investment has plummeted over the last decade, as the chart shows. Colombia’s FDI inflows for 2024 totaled $14.1 billion, a sharp decline from the $16.8 billion received a year earlier and 13% less than the $16.2 billion received 10 years earlier.

Source: Central Bank of Colombia.

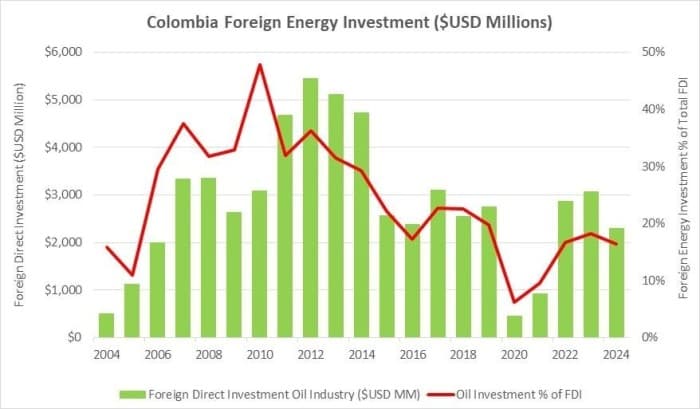

A key reason for the sharp decline in foreign spending on businesses in Colombia is the drop in energy investment. For 2024, Colombia received $2.3 billion of offshore capital, which was invested in the strife-torn country’s energy patch. This was significantly lower than the $3.1 billion of foreign investment directed to the petroleum industry during 2023.

Source: Central Bank of Colombia.

While full-year data for 2025 is yet to be made available, there are signs of an uptick in foreign investment in Colombia’s oil industry. For the first six months of the year $1.5 billion was invested in the hydrocarbon sector compared to $1.3 billion for the same period a year earlier. Whether that trend will continue is questionable because of the headwinds impacting Colombia which are deterring foreign investment. This includes U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to decertify the strife-torn country as a counter-narcotics partner and his escalating feud with President Petro.

These developments, coupled with sharply weaker oil prices and the growing global push to phase out fossil fuels in favor of electric vehicles and renewable sources of energy, mean time is running short for Colombia to discover more oil. Indeed, it will take considerable amounts of capital to fund the tremendous amount of drilling activity required to make the required petroleum discoveries. It is incredibly difficult to attract the required investment, with Bogota refusing to award new exploration contracts while increasing the tax burden faced by oil companies. Surging violence and cocaine production, particularly in the remote regions where Colombia’s oil industry operates, are further deterring foreign energy investment.

By Matthew Smith for Oilprice.com

No comments:

Post a Comment