From Frozen Periphery to Strategic Corridor

For much of modern history, the Arctic Ocean was a geographic afterthought—too remote, too frozen, and too unpredictable to matter for global commerce. Today, that perception is changing. As climate conditions evolve and geopolitical fault lines reshape global trade, the Northern Sea Route (NSR) along Russia’s Arctic coast is emerging as a strategic alternative for states willing to tolerate risk in exchange for leverage. No country has embraced this calculation more deliberately than China.

In 2025, Chinese shipping operators completed a record number of container voyages through the NSR, marking a clear departure from earlier years when Arctic transits were largely symbolic or experimental. This was not a publicity stunt or a one-off response to congestion elsewhere. It was the outcome of a sustained effort to turn the Arctic from an abstract future option into a usable, if seasonal, component of China’s global logistics strategy.

The Economic Logic of Distance and Time

At first glance, the appeal of the NSR is straightforward. The passage significantly shortens the distance between northern Chinese ports and northern Europe compared with the traditional route through the Indian Ocean and the Suez Canal. In ideal conditions, the Arctic path can reduce sailing time by up to two weeks. For shipping companies operating on thin margins and tight schedules, that difference matters. Shorter voyages mean lower fuel consumption, faster asset turnover, and potentially lower emissions per container.

Yet geography alone does not explain China’s growing interest. The commercial advantages, while real, are insufficient to justify the political and operational risks of Arctic navigation. The deeper logic lies elsewhere.

Strategic Vulnerability and the Search for Diversification

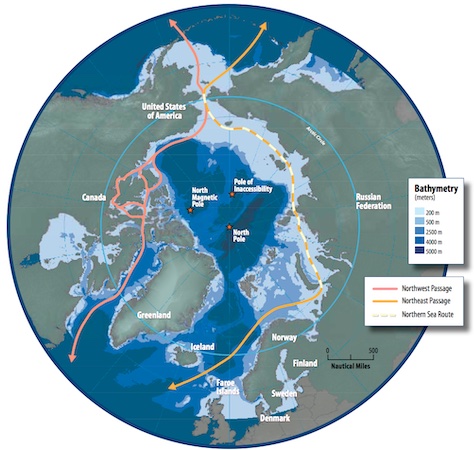

Map of the Arctic region showing the Northern Sea Route, in the context of the Northeast Passage, and Northwest Passage. Credit: Arctic Council, Wikipedia Commons

Map of the Arctic region showing the Northern Sea Route, in the context of the Northeast Passage, and Northwest Passage. Credit: Arctic Council, Wikipedia CommonsOver the past decade, Beijing has become increasingly uneasy about its reliance on maritime chokepoints controlled or influenced by rival powers. The Strait of Malacca, the South China Sea, and the Suez Canal all sit within regions where political instability, military competition, or conflict can rapidly disrupt trade. The recent crisis in the Red Sea showed just how quickly a localised conflict can reverberate through global supply chains

From this perspective, the NSR functions not merely as a transit route but as a mechanism for economic diversification, representing a strategic consideration in Beijing’s long-term trade and security planning. Chinese officials have even referred to it as the Arctic ‘Golden Waterway’ (黄金水道, huangjin shuidao), with some in China estimating that its use could generate cost savings of up to $120 billion each year. Even if it operates only part of the year, the route provides China with an alternative corridor geographically distant from many of the world’s most volatile maritime flashpoints. In an era defined by strategic hedging, that alone gives the Arctic route outsized importance.

Building Experience Where Others Hesitate

China’s Arctic engagement has been methodical, not rushed. Over the past several years, Chinese shipping firms—many with close state ties—have steadily accumulated experience navigating ice-prone waters. Each voyage has added to a growing body of operational knowledge: how to time departures, how to co-operate with Russian icebreakers, how hulls and engines perform in extreme cold, and how Arctic weather patterns disrupt schedules. While Western shipping companies have largely stayed away, Chinese operators have quietly built a learning advantage.

This absence of Western competitors is not accidental. Sanctions, regulatory uncertainty, environmental concerns, and reputational risk have made many European and North American firms reluctant to engage with a route so tightly controlled by Russia. For China, however, this hesitation has created opportunity. With fewer players involved, Beijing gains disproportionate influence over emerging norms and practices, even without formal authority in the Arctic.

Partnership with Russia: Enabler and Constraint

That influence is exercised through partnership with Russia, the primary gatekeeper of the NSR. Moscow considers the corridor part of its internal waters and enforces a regulatory regime requiring foreign vessels to seek permission, pay fees, and often accept icebreaker escorts. For China, cooperation with Russia is both enabling and constraining. It grants access to a route otherwise unusable, but this does not imply that Russia’s control of the NSR is absolute, uncontested, or universally recognised; China’s Arctic ambitions remain subject to broader geopolitical dynamics as well as Moscow’s political and economic fortunes.

This relationship has deepened as Russia has turned eastward in response to Western sanctions. Chinese cargo volumes, investment, and technological collaboration help sustain Russia’s Arctic infrastructure ambitions, from port development to icebreaker fleets. In return, China gains predictable access to the route and a role in shaping its commercial future. The arrangement is pragmatic rather than sentimental, rooted in overlapping interests rather than trust.

Operational and Environmental Constraints

Despite its growing use, the NSR remains a demanding environment. Ice conditions are improving on average, but variability remains high. A single storm or cold snap can close sections of the route with little warning. Search-and-rescue infrastructure is sparse, and emergency response times are long. Insurance premiums remain elevated, reflecting limited historical data and the high potential costs of accidents in remote waters. For now, these constraints ensure that Arctic shipping supplements rather than replaces established routes.

Environmental concerns add another layer of complexity. The irony of Arctic shipping is that it exists because of climate change, yet it risks accelerating environmental damage in one of the world’s most fragile ecosystems. Increased vessel traffic raises the likelihood of fuel spills, black carbon emissions, and disruptions to marine life. These concerns resonate strongly in Western policy debates and contribute to reluctance among Western firms to participate. China, while acknowledging environmental risks, has shown greater willingness to proceed incrementally rather than wait for consensus.

The Polar Silk Road (PSR) and Strategic Presence

Strategically, China frames its Arctic engagement under the banner of the Polar Silk Road, an extension of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) into the high Arctic. The PSR is China’s Arctic adaptation of the BRI, emphasising shipping routes, resource access, and scientific collaboration in a region where it holds no territorial claims. Unlike conventional BRI corridors, which rely on land or traditional maritime passages, the PSR leverages the NSR and other Arctic maritime paths as seasonal, high-risk trade channels that offer shorter connections between East Asia and Europe. Conceptually, it is part of China’s broader ‘Silk Road’ framework, now spanning multiple domains—land, sea, digital, and polar—reflecting an integrated vision of global connectivity.

This framing highlights connectivity, development, and cooperation, while also serving an additional, less overt function. Regular use of the NSR can normalise China’s presence in a region where it lacks territorial claims, though it considers itself a ‘Near-Arctic State’. Over time, operational presence may translate into political influence, particularly in governance forums where practical experience carries weight.

The implications extend beyond shipping. The Arctic is increasingly a theatre of great-power competition, fraught with new tensions and uncertainties, intersecting with questions of energy access, military mobility, and technological infrastructure. Perhaps nothing illustrates the volatility and unpredictability of Arctic security more clearly than the Trump administration’s rhetorically aggressive posture toward Greenland and the question of acquisition or annexation by military means—a posture that prompted several European countries to deploy military forces in response, even against a longstanding ally. While China’s Arctic activities remain commercial in form, they inevitably intersect with broader strategic issues and calculations as the region becomes more accessible and increasingly contested.

A Contingency, Not a Replacement

For global trade, the rise of the NSR does not herald a sudden re-routing of commerce away from traditional canals. Volumes remain modest, and the route’s seasonality limits its reliability. Conversely, its increasing utilisation signals a world in which trade routes can no longer be assumed secure or uncontested. They are actively diversified, politicised, and integrated into national security strategies.

China’s Arctic push reflects this reality: the NSR is not a replacement for the Suez Canal, but a strategic option in a fractured world. For China—a country with an extensive coastline, yet whose access is constrained by maritime chokepoints and Western-aligned states—alternative routes such as the NSR provide strategic flexibility. Beyond the Arctic, China remains exposed to other critical maritime bottlenecks that could disrupt the flow of essential commodities, including the Strait of Hormuz, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, and the Strait of Malacca (key chokepoints along the Red Sea and Indian Ocean).

Each successful voyage strengthens the NSR, shifting the Arctic from an experimental theatre to a viable contingency. The NSR remains harsh, risky, and dependent on cooperation with Russia—but it is no longer theoretical. As climate, commerce, and competition converge, China’s steady advance into Arctic shipping suggests that the future of global trade may be colder, more complex, and increasingly contested than the routes that came before.

Scott N. Romaniuk

Dr. Scott N. Romaniuk is a Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Contemporary Asia Studies, Corvinus Institute for Advanced Studies (CIAS), Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary.

No comments:

Post a Comment