Carney and Thucydides at Davos

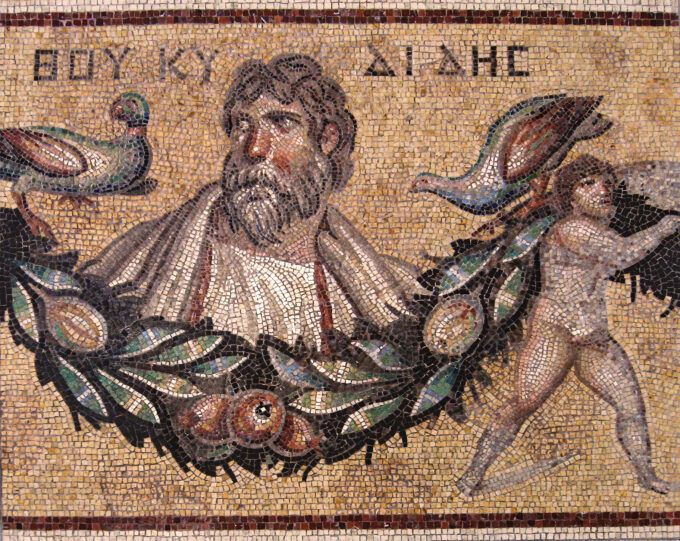

Thucydides Mosaic from Jerash, Jordan, Roman, 3rd century AD at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin – Public Domain

You gotta love a speech that opens with Thucydides.

For those of us steeped in the ideas of George Kennan, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s call for “value-based realism” and a “third way” of middle powers at the Davos Summit, sounded too good to be true. On its face, it was a great speech, a call to arms with Canada in the lead. Carney is being hailed as “Churchillian” and the “new leader of the Free World,” his speech, “historic”—one for the books. But how realistic is his realist prescription? Let’s hope that he understands the implications of his1 Thucydides quote.

At last, I thought, a national leader who speaks my language. Carney blew the lid off of the “rules-based international order” that gave us 80 years of undeclared wars of choice, dozens of regime change efforts, and the de facto imperialism, disparities, and wage slavery of economic globalization. He spoke of not going back, of a “rupture” with a past that he called out as the emperor’s new clothes enabled by the “go along to get along” compliance of second-tier nations. He shamed European nations for their fealty and offered a plausible-sounding middle way of “greater strategic autonomy” for middle nations based on a diversified scheme of “principled pragmatism” and a “variable geometry” of alliances. A brave man, I thought, an honest and rational man—a man with a plan.

Shattering the possibility of a return to the recent past of middle-powers subservience, he starkly heralded the arrival of the new world order we already knew was here and stood up to the U.S. administration without mentioning names. Since Davos, he has reaffirmed his position. And yet Carney seems unaware of a powerful internal contradiction in his vision that could scuttle it: Realism is based in part on the idea of bilateral agreements of independent sovereign nations acting unfettered in their own interests. But in order to be effective, the middle powers would presumably have to band together into an aggregated great power through multilateral agreements tailored to the interests of its constituent nations. He also spoke of linking the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) with the European Union (EU), which sounds like the very apotheosis of multilateralism.

Under the neoliberal world order, multilateralism had been a part of the problem, yet in order for Carney’s plan to work, middle nations would have to comprise one of the poles of the emerging multipolar world by becoming a united front conglomerate speaking with a single voice. This is because there is safety and power in numbers, and by definition, middle powers fill the gap between great powers and the lesser powers. They tend to be technologically advanced with prominent middle classes, but are smaller than the monster nations. Too small to “go it alone,” they would have to enter into a multilateral pacts of “variable geometry,” depending the agreement and its signatories. Such a league would also, by the Prime Minister’s account, act as a brake on hegemonic rivalries. Medium-sized nations would also have to do business with the monster nations as sovereign states (as witnessed by Canada’s new “strategic partnership” with China), even though Carney admits that great powers typically have the advantage.

Someone who has already identified this problem of middle states acting as unencumbered sovereigns, is the University of Chicago professor and standard-bearer of neorealism, John Mearsheimer. Mearsheimer’s school of offensive realism, holds that the direction and nature of the global order is determined by the competition of great powers, and not by leagues of middle-tier nations. The question is whether or not Mearsheimer is right in this overarching observation.

I prefer Kennan’s brand of realism based on intuition, a broad, deep, and nuanced understanding of history, culture, and human nature, to the determinism of Mearsheimer (to be fair, Mearsheimer’s vision is also based on a profound historical understanding). If Mearsheimer was merely saying that the world tends to be governed by the rivalries of great powers, I would tend to agree with him. If he was saying that great powers act most effectively when they act in the moderate and rational furtherance of their perceived interests, or that they usually do (or do not at their own peril), then I would also agree with him. If by contrast, he is asserting a law-like “hidden hand” phenomenon at work, like the physical constants of physics, then I say that his view is too mechanistic, too historicist for the real (read: chaotic) world. As Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., a realist in the law, observes in a different context that “General propositions do not decide concrete cases.” Piecemeal problem-solving is preferable to grandiose meta theories.

That said, and in spite of his broader views, I have found that Mearsheimer is usually spot on in his proximate analyses of events large and small (his 2014 Foreign Affairs article, Why the Ukraine Crisis is the West’s Fault,” predicting a war with Russia over Ukraine in response to the eastward expansion of NATO, has proved prescient, as have his analyses of events in Ukraine since the Russian invasion). But the central tenet of objective realism is too deterministic and does violence to the complexities of a disorderly world based on power struggles that are guided, not only by reason and interest, but also on ideology/eschatology, “morality,” human caprice, and irrationality. Error is frequently a driver of events, and history is as much of sequence of screwups as successes. The human world is not governed by mechanistic principles or “laws” of history, but by currents and tendencies, which may be strong or weak. Human interaction is both a randomizing factor as well as an ordering principle, and history takes on a will of its own that is beyond human intentions.

But let us assume for a moment that Mearsheimer’s historical Newtonianism holds true in this instance—that middle nations cannot run the table as individual players or as brokers of consolidated power. This would mean that they would have to act collectively as a league of sort of powerful states. As retired Colonel Douglas Macgregor recently observed, NATO—that great pact of middling vassal states—was (and is) too diverse in its interests and agendas to function effectively: “NATO remained exactly what it was: a chorus of competing voices that could not agree on much of anything.” The impotence of the NATO’s “limited liability partnership” in respect to the Russo-Ukrainian War, is just a recent example of Macgregor’s point (on a side note, Carney’s ”coalition of the willing”—which is willing to fight to the last Ukrainian—sounds a lot like the phenomenon he is criticizing, but let that go). Macgregor’s criticisms of an overly-diverse military alliance may find parallel in economic alliances of self-interested middle powers a la Carey.

The question then is whether or not Mearsheimer’s great powers principle and Macgregor’s observation on the inverse relationship of nation interest diversity and efficacy, apply to the present case and whether great powers geopolitics will preclude Carney’s prescription. In the words of the Zen master in the parable from Charlie Wilson’s War, “We’ll see.”

The Thucydides Trap

Carney’s Thucydides quote that “The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must,” must be taken in the context of another famous quote by the Greek historian on the cause of the Peloponnesian War: “The growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Sparta, made war inevitable.”

This illustrates another dynamic at play in the world—another inverse relationship—that is sometimes called the “Thucydides Trap” (or as I used to call it: the Problem of the Declining Hegemon). It refers to the inherent danger of periods in which a waning hegemon is confronted with a rising or reinvigorated hegemon, and tends to support Mearsheimer’s position. In Greece in 431 BC, the rising power was Athens and the declining power was Sparta. In the first half of the 20th century, the declining hegemon was the British Empire and the rising powers were Germany and Japan (and the US as an industrial trading partner of Britain). This was also the period of the World Wars.

Today the declining hegemon is the United States. As it slides into political decadence and senescence, we can only imagine where the Lear-like policies at home and abroad will lead. The primary rising power is China, in cooperation with Russia, Iran, and perhaps India. These powers would have competed with the West for the favor and resources of the Global South as the Earth’s biosphere continues to degrade. But now Carney has made a unified Western alliance problematic by encouraging its intermediate constituent states to peal off from the occidental pole.

With the help of erratic U.S. policies, the West could split, with modern, technologically-advanced nations like Canada and Australia poised to go their own way or as leaders of “variable geometry” alliances of similarly-situated nations. But will it work? After all, the most subservient client states of the United States—those of Western Europe—appear to have stood up to the U.S. over Greenland. But was this a one-off? Was the rhetoric over Greenland a bridge too far, even for Western Europe? With an American president who seems content to abandon Europe, could Canada realistically position itself as the senior partner of the NATO alliance? We’ll see.

We know of Canada’s new trade treaty with China, but as a general program, we need details of what the third way is and how it is supposed to work. Would the middle nations compete or cooperate or would they adhere to one of the oldest realist tenets of all: nations compete when they must and cooperate when they can. Would they band around one of the poles of the great powers, and if so, how would what would be a new approach? Would Carney’s third way provide the basis for a BRICS-like league for middle powers? Would it be a balancing factor or a potential spoiler in the competition of great powers? We need more answers on how the new way will work if we are to assess if it will work.

If I had to guess, I would say that Carney’s middle way will not fully materialize in the way he would like, and that the tenet of Thucydides he quoted, if extrapolated, will hold true, that in terms of power, middle nation are just better versions of lesser powers, and diverging interests will undermine any effort for them to assert themselves en masse as a collective great power. Another possibility is that the differing interests of middle powers will form an elaborate, overlapping, kaleidoscopic array of ever-shifting alliances and “buyers’ clubs” depending on the specifics of interests and threats in question. Whether such a busy system of alliances will work is anybody’s guess.

A final possibility is that Carney and Canada will lead the charge and nobody will follow. When Theodore Roosevelt gave the initial order to attack the Spanish forces on Kettle Hill, only five men followed because they could not hear him over the din of battle. The difference is that everybody heard Carney at Davos. To be fair, Roosevelt and his men took Kettle and San Juan Hills (at the cost of one fifth of the regiment). Is Carney a new Churchill or TR? We’ll see.

The world order is shifting with abrupt ruptures from the past and a United States that appears to have taken the Madman Theory of foreign policy taken to a chaotic extreme. With China on the ascendance, and the U.S. in what appears to be in a state of steep and perhaps permanent decline, which will win the the Global South? Let’s hope that the middle nations of the West and Pacific rim will embrace Carney’s proposal, and that combinations of them can allow their members to punch above their weight as a force for stability and sanity in the world.

Of course the overarching question is whether or not an increasingly volatile U.S. can navigate the new geopolitical seas in peace. Russia has shown great restraint vis-a-vis Western meddling in the proxy war on its front doorstep. Likewise, the Western Pacific, where Mearsheimer and others believe a great powers struggle with China might be in the offing in the future, is currently pacific. By contrast, as Macgregor asks, “Who has stopped, boarded, and seized a [foreign-flagged] commercial vessel? We have.”

Conclusion

The emerging world order, like a great Shakespearean tragedy, denotes a crisis-within-a-crisis: a shift of power away from the United States as other powers rise and allies are driven away. This shift exists within the greater crises of the environment. If the world is to effectively address these existential crises, it will require a critical mass of great, medium, and lesser powers cooperation. As I have written elsewhere, the world can no longer afford the infantile rivalries of the Great Game. The problem with the Great Game is the game itself.[1]

It is a tall order for a great speech, even one beginning with Thucydides, to launch a new geopolitical era. And if successful in doing so, there is no guarantee that the new order will play out anything like the way the author intended. Given the greater crises that loom above humankind and which now threaten us all, what would be the impact of Carney’s middle prong of the new world order? If it materializes, it could provide a source of moderation and balance in the world. Or it could be just another axis in a balkanizing world order at a time when greater cooperation is needed. We can hope for the best, but should not expect it. We shall see.

NOTES

1. See Michael F. Duggan, “Realism and Regionalism: The United States in a Multipolar World,” Chicago Journal of Foreign Policy, April 24, 2024. ↑

No comments:

Post a Comment