Washington’s Cult of the Bomb

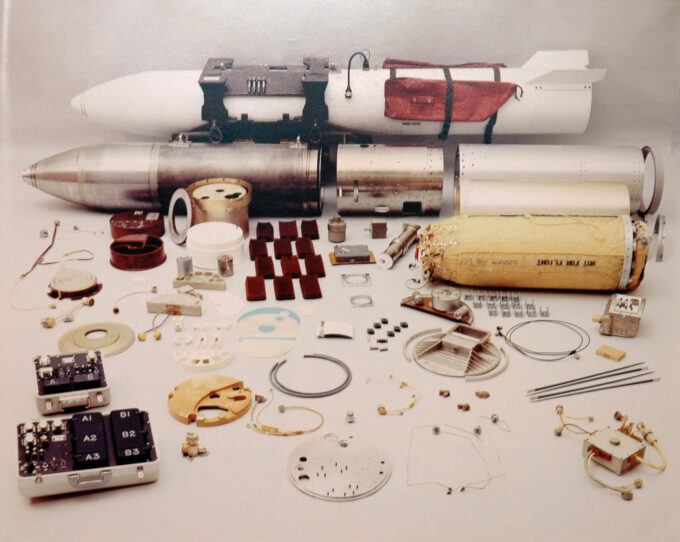

Components of a U.S. B83 thermonuclear weapon. Photograph Source: Chuck Hansen – Public Domain

The first of the bombs used against Japan, the one that flattened Hiroshima, produced a blast equivalent to about 15,000 tons of TNT and killed tens of thousands of innocent people in minutes. Fast-forward to the ‘70s: the United States’ B83 bomb “is by far the most destructive weapon in the US nuclear arsenal,” capable of producing an explosion about 80 times stronger than the one used against Hiroshima. And we have seen nuclear weapons even more fathomlessly destructive: the Soviet Union produced a weapon, called Tsar Bomba, whose “detonation was astronomically powerful—over 1,570 times more powerful, in fact, than the combined two bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Today’s nuclear bombs do not operate the way that the “fat man” bombs of WW2 did, but use bombs like those as triggering devices to set off much larger explosions. It’s important for us to understand that a nuclear exchange today could well end human civilization. It could even end human life altogether. Given the power of today’s nuclear weapons and the capacity to compound that power using modern delivery systems, we are in totally uncharted territory. Anyone who says that the destruction could be controlled or hemmed in is lying: as we will discuss, even much smaller and less sophisticated weapons consistently produced explosions that are far larger than expected. The nuclear warheads of our time belong in a different category conceptually from those the U.S. government used on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. Today’s bombs are qualitatively different in their destructive power.

Among the most remarkable, if little-known, defining features of American nuclear testing has been the consistent inability of supposed experts to accurately predict the power or consequences, in either the short or long term, of the explosions. In the short term, the blasts were consistently larger and more damaging than expected, with larger radiuses, more fallout, and higher TNT equivalents. In the long term, so-called experts have consistently (and I think, given the surrounding facts, quite intentionally) under-stated and under-counted the health consequences associated with the nuclear fallout associated with the explosions. From where I sit, it seems nuclear weapons have now embodied a quasi-religious or cultic death fetish, and I think this has seeped into politics and ideology in a number of ways. This stands to reason. With God long dead, with politics uglier and more nihilistic by the day, billionaires more delusional by the second, it is easy to understand the sadistic tendency to crank your neck and watch the crash. For a person like Trump – and to be sure, many American presidents fall into the same category; indeed an American president is the only one to have committed those unthinkable atrocities – the only thing left is abstract power, pure, destructive power, loosed from any rational thought or humane impulse. I think this kind of death-drive is a very real and tangible feature of our culture in America today.

Everyone is scared of Trump with the nuclear button, as they well should be, but few among our elite chattering classes care to tell you the whole truth. All of Washington, across both parties, has been thoroughly invested in aestheticizing and fetishizing nuclear weapons for decades. It has been an active and explicit goal of the U.S. government to help prosecute and manage this campaign. Billions of dollars have gone to these efforts, through cultural and museum practices, through curatorial choices and “educational” materials for children on just how darn cool the Manhattan Project was. I understand that you’re not supposed to discuss this in the West. Look, we can enjoy Christopher Nolan movies, and we can assume “our leaders” mean well, but we are all actively fetishizing nuclear weapons, and thus fascinating over the extinction of humanity. I can recall some several years back, a friend of mine among the Pueblo peoples sent me a presser from the Los Alamos Study Group, which was very much appreciated at the time and remains so. The Group’s director, Greg Mello, had spoken with real clarity on this, our culture’s nuclear death fetish, in a response to the dedication of an incredibly vulgar and tone-deaf, nearly full-sized recreation of the tower used in the Trinity test:

This exhibit fetishizes utter destruction. Lifting up the Trinity “Gadget,” the first plutonium bomb, is visually akin to a nuclear Black Mass. It celebrates the inversion of human values, which was the principal moral and political inheritance of the Manhattan Project. It celebrates a death cult.

I couldn’t say it any better than Mello. The way we have approached this topic points to a cultural sickness or moral atrophy, and that naturally leads to these attitudes we see amongst the powerful. They are downright cavalier on the topic, which evinces either their ignorance or their insanity. As a middle-aged American, I have heard no shortage of intelligence-insulting nonsense from politicians of both parties, but there has never been anything quite like the idea of a “tactical” nuclear weapon. If you know anything about how these weapons work in real life, there is no way to sustain this warped notion. The difference between “strategic” and “tactical” nuclear weapons would break down almost immediately in real life, that is, assuming that it is even a real distinction in theory. Given the power of today’s nuclear weapons, it makes no practical sense to talk to this and can only serve to expose us to more danger.

The fiction that there are any low-yield nuclear weapons only encourages miscalculations and exchanges. Annie Jacobsen’s book contains a good discussion of how the structure of the system favors mistakes that could lead to the firing of a nuclear weapon. This is the height of today’s rational irrationality in Adorno/Horkheimer’s terms, the absolutely batty idea that we could start lobbing “low-yield” nukes at each other as a tactical option. The reality is that these “tactical” weapons are capable of producing blasts well in excess of the fat man style bombs used against Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Today’s technologies permit dial-a-yield functionality, meaning you can decide how many innocent people you want to kill like you’re playing a video game. Some of today’s variable yield “tactical” bombs can give you several times a Hiroshima explosion. But I guess we just expect that they’ll dial the tactical ones back to just one Hiroshima each use. Or something? Submarines are towing these weapons around day and night, all the time (and that’s to say nothing of the strategic big guns). Testing them was a very bad idea in the ‘50s, and it is an even more ill-fated idea today. Everyone, everywhere, of any political spectrum or style should speak with one voice on the question of nuclear weapons. It is not a question at all. It can’t be on the table in any way, whether it be testing or use in war.

American politicians and public officials of both parties have been virtually silent on the question of nuclear weapons for decades on end, and that is intentional and carefully tended to by staff; when they’re not silent, even the “liberal” ones tend to use their words in support of nuclear build-up and escalatory language in the direction of Washington’s major adversaries. At least prior to Trump, the very few congressional voices for peace and a more sane, diplomatic foreign policy have been smeared as unserious and insufficiently committed to national security. That is, our politics is completely lost on this issue and all of its major institutional incentive structures point the country’s leaders in exactly the wrong direction. My own professional experiences confirm that many people on the Hill and in Beltway policy circles still harbor deep misunderstandings and false beliefs about the power of nuclear weapons in practical, real-world terms; the probabilities around their own survival; the long-term global climatic and temperature consequences of any exchange; the possibility of civilizational collapse; the number of people who will starve, etc. Thus the nuclear cult is not even conservative in any valid sense of that, charitably, trying to carry on with practices that have worked in the past. It is rather the insane collective death worship that made the Soviets produce the horror of the Tsar Bomba, and that compelled us to — like children torturing a bug or blowing things up for no reason — torment the people of the South Pacific with successive tests during Operation Castle. We have not reckoned with this as an American people and society, and that is to our shame. There are so many of these stories that need to be told. I don’t know where to start, but it’s a lot worse than I thought before I took a look.

If we had responsible and scientifically literate leaders (and this really is both parties in the U.S.), we would approach this differently domestically and in diplomatic terms. With respect to our nuclear obligations abroad, Trump is turning up the volume on longstanding U.S. practices of doing whatever the hell we want and readily disregarding agreed-to treaty terms. As an aside, the reason I am so careful to point out the duplicity and shamelessness of the British is because our ruling class gets its whole style of “diplomacy” from this skullduggery. And I don’t think it’s a very good or effective way to be a global citizen – and I know I’m very naive and silly to think Americans should care. But as good and diligent students of history, as careful people, we know that what goes up must come down. And so global citizenship remains important, as it has been through the ages.

But Donald Trump insists upon unilateral prerogative. Sound familiar? We are having the same debate we were having during the unfortunate George W. Bush era; there are two different registers of unilateral power working here I think, and they are related but distinct. We have been having a longstanding conversation about unilateral power as executive power within the U.S. government; and about unilateral power in terms of the U.S. making decisions at the planetary scale while accepting no input from anyone else. So Trump only makes it explicit again, though I am not downplaying the danger. From the evidence of his public remarks, Trump is attracted to the topic of nuclear weapons and nuclear wars. Americans like them, too, whether admitting it or not. But as bad as war is, if we must continue to do it, we have to stay here and go no further.

To my mind, nothing in international law is more clear than that any use of a nuclear weapon is illegal, impermissible, and a war crime. Nuclear blasts necessarily kill innocent civilians and needlessly incapacitate medical infrastructure – they literally vaporize everything in a radius that could today go out for miles. International courts like the ICJ have provided totally incoherent and substantively incorrect guidance on this precisely because they do not understand the factual situation, which has nothing to do with the law. (This is why I’ve always been with Richard Posner on the importance of facts in cases. We could avoid most of our strange and unnecessary legal curiosities with more attention to and understanding of what is actually happening, but I’ll save that rant.) The point is that it is impossible, here in the world of flesh and blood, to use a nuclear weapon and yet provide what international law requires for protection of civilian lives, children, etc. It is not possible and it never was, even in 1945. As we’ve discussed, many of the United States’ most renowned military men (including Dwight Eisenhower) strongly opposed the use of nuclear weapons as dishonorable in their bringing civilians into the mess unnecessarily and wantonly. It was the political system that first required and demanded the bomb. The most honorable generals and admirals looked on nuclear weapons with horror and disgust, as they would child-killers. We don’t have much of that kind of quaint ethical sensibility today, at least not in the political class (to be sure, it remains widespread amongst regular people.

What very few today recognize is that these cultural features come only at the end of a collapsing spiral of cultural differentiation and meaning. The billionaires who believe they will be able to escape into space may be surprised by how quickly a nuclear exchange destroys even the most basic infrastructures, to say nothing of high tech. Nothing will be far enough underground, nowhere close. As in other ways, today’s global ideologies are alike in their most important and fundamental features. And in the discourse about state capitalism, we can see how they are all converging. It is remarkable to watch how MAGA state capitalism and Communist Party state capitalism are converging before our eyes; the global ideal is this marriage of the state and capital, and it is now more openly acknowledged that the state not only is a capitalist, but must be one. This is the conversation today amongst both government officials and the billionaires of our country: how can the U.S. government not be in the game when the Chinese are starting new investment funds and participating in the market in this very active and intentional way in the direction of the Party’s ends?

Once the bombs stop flying, if anyone is alive, they will be living in a nightmare, no matter where they are in the world. Global temperatures will plummet as the soot and dust spread and block the sunlight. Many crops could yield one-tenth of what they had before. There will be chaos, like even those in the most war-torn parts of the world can’t imagine, because there will be no plausible hope for aid, as even the “richest” people fight and kill to survive. Our leaders just plain aren’t being serious in the way they talk about nuclear weapons. Given our track record on predictions around blast yield and overall harm (for example, vastly underestimating after-the-fact harm from medical issues associated with exposure to radiation), it is highly likely that even our current worst-case scenarios underestimate the harms from a nuclear war. The good news is that all countries and all human beings share in this risk equally, whether they realize it or not. The old term says the truth: mutually-assured destruction. Every country should challenge each other to reduce their nuclear arms. We have done this. There are fewer today than during the height of the Cold War. This competition would be a bonanza for humanity and its long-term prospects. Show us how responsible you can be.

We have to stress the failure of our predictive power because this is the thing the technocratic class hangs its hat on, and I think this returns us again to the dialectic of enlightenment. There is some kind of epistemic failure or contradiction here obviously, because scientific-bureaucratic rationality has not been able to accurately represent this phenomenon. And it can’t contain it. As mentioned above, it is the political that’s driving nuclear death-worship. To this point, I don’t think a factual reminder is enough for everyone, not if their nuclear death religion is the driver. And that is still most national-level politicians in our country; these folks are supposed to be in the reasonable center of something. That’s the depth of the rot in our political language. We all participate in it. The work of Jean Baudrillard speaks directly to this moment:

The scandal is that experts have calculated that a state of emergency declared on the basis of a prediction of seismic activity would trigger off a panic whose consequences would be more disastrous than the catastrophe itself. Here again we are fully in the midst of derision: in the absence of a real catastrophe it is quite possible to trigger one off by simulation, equivalent to the former, and which can be substituted for it. One wonders if this is not what fuels the fantasies of the “experts” – which is exactly the case within the nuclear domain: isn’t every system of prevention and deterrence a virtual locus of catastrophe? Designed to thwart catastrophe, it materializes all of its consequences in the immediate present. Since we cannot count on chance to bring about a catastrophe, we must find an equivalent programmed into the defense system.

The End of New START and the Enduring Nuclear Nightmare

On February 5th, with the expiration of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or New START, the only bilateral arms control treaty left between the United States and Russia, we are guaranteed to find ourselves ever closer to the edge of a perilous precipice. The renewed arms race that seems likely to take place could plunge the world, once and for all, into the nuclear abyss. This crisis is neither sudden nor surprising, but the predictable culmination of a truth that has haunted us for nearly 80 years: humanity has long been living on borrowed time.

In such a context, you might think that our collective survival instinct has proven remarkably poor, which is, at least to a certain extent, understandable. After all, if we had allowed ourselves to feel the full weight of the nuclear threat we’ve faced all these years, we might indeed have collapsed under it. Instead, we continue to drift forward with a sense of muted dread, unwilling (or simply unable) to respond to the nuclear nightmare. In a world already armed with thousands of omnicidal weapons, such fatalism — part suicidal nihilism and part homicidal complacency — becomes a form of violence in its own right.

Given such indifference, we risk not only our own lives but also the lives of all those who would come after us. As Jonathan Schell observed decades ago, both genocide and nuclear war are distinct from other forms of mass atrocity in that they serve as “crimes against the future.” And as Robert Jay Lifton once warned, what makes nuclear war so singularly horrifying is that it would constitute “genocide in its terminal form,” a destruction so absolute as to render the earth unlivable and irrevocably reverse the very process of creation.

Yet for many, the absence of such a nuclear holocaust, 80 years after the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, is taken as proof that such a catastrophe is, in fact, unthinkable and will never happen. These days, to invoke the specter of annihilation is to be dismissed as alarmist, while to argue for the abolition of such weaponry is considered naïve. As it happens, though, the opposite is true. It’s the height of naïveté to believe that a global system built on the supposed security of nuclear weapons can endure indefinitely.

That much should be obvious by now. In truth, we’ve clung to the faith that rational heads will prevail for far too long. Such thinking has sustained a minimalist global nonproliferation regime aimed at preventing the further spread of nuclear weapons to so-called terrorist states like Iraq, Libya, and North Korea (which now indeed has a nuclear arsenal). Yet, today, it should be all too clear that the states with nuclear weapons are, and have long been, the true rogue states.

A nuclear-armed Israel has, after all, been committing genocide in Gaza and has bombed many of its neighbors. Russia continues to devastate Ukraine, which relinquished its nuclear arsenal in 1994, and its leader, Vladimir Putin, has threatened to use nuclear weapons there. And a Washington led by a brazen authoritarian deranged by power, who has declared that he doesn’t “need international law,” has stripped away the fragile façade of a rules-based global order.

Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, and the leaders of the seven other nuclear-armed states possess the unilateral capacity to destroy the world, a power no country should be allowed to wield. Yet even now, there is still time to avert catastrophe. But to chart a reasonable path forward, it’s necessary to look back eight decades and ask why the world failed to ban the bomb at a moment when the dangerous future we now inhabit was already clearly foreseeable.

Every City is Hiroshima

With Hiroshima and Nagasaki still smoldering ruins, people everywhere confronted a rupture so profound that it seemed to inaugurate a new historical era, one that might well be the last. As news of the atomic bombings spread, a grim consensus took shape that technological “progress” had outpaced political and moral restraint. Journalist Norman Cousins captured the zeitgeist when he wrote that “modern man is obsolete, a self-made anachronism becoming more incongruous by the minute.” Human beings had clearly fashioned themselves into vengeful gods and the specter of Armageddon was no longer a matter of theology but a creation of modern civilization.

In the United States, of course, a majority of Americans greeted the initial reports of the atomic bombings of those two Japanese cities in a celebratory fashion, convinced that such unprecedented weapons would bring a swift, victorious end to a brutal war. For many, that relief was inseparable from a lingering desire for retribution. In announcing the first atomic attack, President Harry Truman himself declared that the Japanese “have been repaid many fold” for their strike on Pearl Harbor, which inaugurated the official American entry into World War II. Yet triumph quickly gave way to a more somber reckoning.

As the scale of devastation came into fuller view, the psychological fallout radiated far beyond Japan. The New York Herald Tribune captured a growing unease when it editorialized that “one forgets the effect on Japan or on the course of the war as one senses the foundations of one’s own universe trembling a little… it is as if we had put our hands upon the levers of a power too strange, too terrible, too unpredictable in all its possible consequences for any rejoicing over the immediate consequences of its employment.”

Some critics of the bombings would soon begin to frame their concerns in explicitly moral terms, posing the question: Who had we become? Historian Lewis Mumford, for example, argued that the attacks represented the culmination of a society unmoored from any ethical foundations and nothing short of “the visible insanity of a civilization that has ceased to worship life and obey the laws of life.” Religious leaders voiced similar concern. The Christian Century magazine typically condemned the bombings as “a crime against God and humanity which strikes at the very basis of moral existence.”

As the apocalyptic imagination took hold, others turned to a more self-interested but no less urgent question: what will happen to us? Newspapers across the country began running stories on what a Hiroshima-sized bomb would do to their downtowns. Yet Philip Morrison, one of the few scientists to witness both the initial Trinity Test of the atomic bomb and Hiroshima after the bombing, warned that even such terrifying projections underestimated the danger.

Deaths in the hundreds of thousands were, he insisted, far too optimistic. “The bombs will never again, as in Japan, come in ones or twos. They will come in hundreds, even in thousands.” And given the effect of radiation, those who made “remarkable escapes,” the “lucky” ones, would die all the same. Imagining a prospective strike on New York City, he wrote of the survivors who “died in the hospitals of Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Rochester, and Saint Louis in the three weeks following the bombing. They died of unstoppable internal hemorrhages… of slow oozing of the blood into the flesh.” Ultimately, he concluded, “If the bomb gets out of hand, if we do not learn to live together… there is only one sure future. The cities of men on earth will perish.”

One World or None

Morrison wrote that account as part of a broader effort, led by former Manhattan Project scientists who had helped create the bomb, to alert the public to the newfound danger they themselves had helped unleash. That campaign culminated in the January 1946 book One World or None (and a short film). The scientists had largely come to believe that, if the public had their consciousness raised about the implications of the bomb, a task for which they felt uniquely responsible and equipped, then public opinion might shift in ways that could make policies capable of averting catastrophe politically possible.

Scientists like Niels Bohr began calling on their colleagues to face “the great task lying ahead,” while urging them to be “prepared to assist in any way… in bringing about an outcome of the present crisis of humanity worthy of the ideals for which science through the ages has stood.” Accepting such newfound social responsibility felt unavoidable, even if so many of those scientists wished to simply return to their prewar pursuits in the insulated university laboratories they once inhabited.

As physicist Joseph Rotblat observed, among the many forms of collateral damage inflicted by the bomb was the destruction of “the ivory towers in which scientists had been sheltering.” In the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that rupture propelled them into public life on an unprecedented scale. The once-firm boundary between science and politics began to blur as formerly quiet and aloof researchers spoke to the press, delivered public lectures, published widely circulated articles, and lobbied members of Congress in an effort to secure some control over atomic energy.

Among them was J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos Laboratory where the bomb was created, who warned that, “if atomic bombs are to be added as new weapons to the arsenals of a warring world… then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and Hiroshima,” a statement that left some officials perplexed. Former Vice President Henry Wallace, who had known Oppenheimer as both the director of Los Alamos and someone who had directly sanctioned the bombings, recalled that “he seemed to feel that the destruction of the entire human race was imminent,” adding, “the guilt consciousness of the atomic bomb scientists is one of the most astounding things I have ever seen.”

Yet the scientists pressed ahead in their frantic effort to avert future catastrophe by preventing a nuclear arms race. They insisted that there was no doubt the Soviet Union and other powers would acquire the weapon, that any hope of a prolonged atomic monopoly was delusional, and that espionage was incidental to such a reality, since the fundamental scientific principles needed to build an atomic bomb had been established by 1940. And with Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the secret that a functioning bomb was possible was obviously out.

They argued that there would be no effective defense against a devastating atomic attack and that the U.S., as a highly urbanized society, was uniquely vulnerable to such “city killer” weapons. With vast, exposed coastlines, they warned that such a bomb, not yet capable of being delivered by a missile, could simply be smuggled into one of the nation’s ports and lie dormant there for years. For the scientists, the implications were unmistakable. The age of national sovereignty had ended. The world had become too dangerous for national chauvinism, which, if humanity were to survive, had to give way to a new architecture of international cooperation.

Teaching Us to Love the Bomb

Such activism had its intended effects. Many Americans became more fearful and wanted arms control. By late 1945, a majority of the public consistently supported some form of international control over such weaponry and the abolition of the manufacturing of them. And for a brief moment, such a possibility seemed within reach. The first resolution passed by the new United Nations in January 1946 called for exactly that. The publication of John Hersey’s Hiroshima first as a full issue of the New Yorker and then as a book, with its intense portrayal of life and death in that Japanese city, further shifted public sentiment toward abolition.

Yet as such hopes crystallized at the United Nations, the two global superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, were already preparing for a future nuclear war. Washington continued to expand its stockpile of atomic weaponry, while Moscow accelerated its work creating such weaponry, detonating its initial atomic test four years after the world first met that terrifying new weapon. That Soviet test, followed by the Korean War, helped extinguish the early promise of an international response to such weaponry, a collapse aided by deliberate efforts in Washington to ensure that the United States grew its atomic arsenal.

In that effort, former Secretary of War Henry Stimson was coaxed out of retirement by President Truman’s advisers who urged him to write one final, “definitive” account defending the bombings to neutralize growing opposition. As Harvard president and government-aligned scientist James Conant explained to Stimson, officials in Washington feared that they were losing the ideological battle. They were particularly concerned that mounting anti-nuclear sentiment would prove persuasive “among the type of person that goes into teaching,” shaping a generation less inclined to regard their decision as morally legitimate.

Stimson’s article, published in Harper’s Magazine in February 1947, helped cement the official narrative: that the bomb was a last resort rooted in military necessity that saved half a million American lives and required neither regret nor moral examination. In that way, the opportunity to ban the bomb before the arms race took off was squandered not because the public failed to recognize the threat, but because the government refused to heed the will of its people. Instead, it sought to secure power through nuclear weapons, driven by a paranoid fear of Moscow that became a self-fulfilling prophecy. What followed were decades of preemptive escalation, the continued spread of such weaponry globally, and, at its height, a global arsenal of more than 60,000 nuclear warheads by 1985.

Forty years later, in a world where nine countries — the U.S., Russia, China, France, Great Britain, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea — already have nuclear weapons (more than 12,000 of them), there can be little doubt that, as things are now going, there will be both more countries and more weapons to come.

Such a global arms race must, however, be ended before it ends the human race. The question is no longer what is politically possible, but what is virtually guaranteed if we refuse to pursue the “impossible.” Nuclear weapons are human creations and what is made by us can be dismantled by us. Whether that happens in time is, of course, the question that now should confront everyone, everywhere, and one that history, if there is anyone around to write or to read it, will not excuse us for failing to answer.

This piece first appeared on TomDispatch.

Trump’s Destruction of Diplomacy and Disarmament

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

In one year, Donald Trump has managed to disarm Congress and put our Constitution on life support. The separation of powers has been breached, and our checks and balances have been compromised. Trump’s latest victims are diplomacy and disarmament, a tragedy that few Americans understand. Last week’s tragic demise of the New START Treaty is the latest marker in the decline of the United States.

I’m writing this disarmament obituary from my own experiences earning a PhD in diplomatic history at Indiana University, analyzing Soviet policy at the Central Intelligence Agency for 25 years, and serving on the U.S. delegation as an intelligence advisor at the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks in Vienna, Austria in 1972, when the SALT Treaty and the ABM Treaty were finally completed. This is a tragedy for the national security interests of the United States as well as the entire global community.

The expiration of the New START Treaty will create a dangerous and costly international environment that could lead such non-nuclear states as Japan, South Korea, Turkey, and Poland to seek their own nuclear weapons. The fact that we only have nine nuclear powers is a testament to the success of the Non-Proliferation Treaty that was negotiated in 1968 and 1969 due to Soviet fears of Germany gaining access to nuclear weapons.

Nuclear weapons have returned to the international chessboard with a vengeance as the three greatest nuclear weapons states—the United States, Russia, and China—are devoting vast resources to strengthening and modernizing their nuclear inventories. This nuclear race is taking place despite the vast overkill capabilities that each of them posses.

It’s important to remember that when New START gained ratification in 2010, it was done with a legitimately bipartisan vote of 71 to 21. Today, a similar ratification process would receive virtually no positive votes from the Republicans and possibly several negative votes from the Democrats. It is ironic that one of the strongest congressional voices for arms control and disarmament, Lee Hamilton from Indiana, died on the same day as the expiry of New START.

With the exception of George W. Bush and Donald Trump, who followed the advice of John Bolton and excelled at abrogating arms control agreements, every president over the past 80 years has recognized the value of reducing armaments, particularly nuclear arms. President John F. Kennedy was courageous in taking on the Pentagon and the Department of Defense in pursuing the Partial Test Ban Treaty; President Richard Nixon pursued SALT and the ABM Treaty; even Ronald Reagan came around to appreciate the value of arms control and promoted the INF Treaty that destroyed an entire class of missile systems. Barack Obama did his thesis at Columbia University on arms control, and considered New START one of his greatest accomplishments.

In view of the difficulty and complexity of disarmament negotiations generally, I cannot imagine the Trump administration being capable of dealing with arms control challenges. We already know from Trump’s handling of our European allies and NATO generally that the diplomacy of international negotiations is beyond his capabilities. The fact that sensitive matters dealing with Russia and Ukraine as well as with Israel and Palestine are being mishandled in the hands of two real estate billionaires—Steve Wytkoff and Jared Kushner—is dispositive. The failures of Secretary of State and National Security Advisor Marco Rubio have neutralized the important roles of the Department of State and the National Security Council in dealing with sensitive international issues.

Of course, if you believe that such diplomatic gimmicks as the Board of Peace for Gaza will produce stability, then you will have a different point of view. These are truly tragic times.

Why Not Another Half Trillion Dollars for War?

Normally, when one develops all the symptoms of a disease, the response ought not to be exacerbating the disease, but seeking to cure it. Approaches to healthcare in the United States have gone off the rails, of course, but think about the disease of military spending.

What are some of the symptoms we’ve suffered recently? Wars, bombings, threats of wars, kidnappings of foreign presidents, arming of distant genocides, attempts to take over or control various countries, hatred, resentment, terrorism, wounded veterans, militarized police, militarized culture, militarized borders, militarized occupations of U.S. cities by masked thugs who might shoot you in the face, erosion of the rule of law, corruption of morality, environmental devastation, mass homelessness and refugee crises, endangerment of public safety, impoverishment, loss of civil liberties, exacerbation of bigotry and xenophobia, insuperable impediments to urgently needed international cooperation, and the greatest risk we’ve ever had of nuclear apocalypse.

And what we’ve lost by not spending even some fraction of the trillion dollar military budget on useful things has caused more deaths and more injuries than those directly caused by the militarism. Spending on wars means not spending on the environment, on education, on healthcare, on housing, on transportation, on infrastructure — and that means death and suffering on a massive scale.

The United States government spends by far the most money in the world on its military. Even ICE, it’s domestic paramilitary, costs more than the military of most countries. Adding another half trillion to the trillion-dollar annual military budget is unspeakable madness. Already, per capita, the U.S. government spends more on its war machine than any other except Israel, whose war machine is of course heavily subsidized by the U.S. government. This latest insane proposal from Washington, however, will place both U.S. military spending and U.S. per capita military spending far above and off any chart on which the rest of the world could appear — and that is despite the fact that U.S. military spending is used to pressure other governments of every sort to increase their military spending as well. The profiteers’ products are often found on both sides of a war.

In fact, the ludicrous new fashion of measuring military spending as a percentage of an economy is an attempt to find some measure by which U.S. war spending can be made to seem reasonable — reasonable, however, only to someone who has blindly accepted the notion that maximizing military spending without limit is a public service, a philanthropic enterprise, rather than a disease.

If impoverishing our future generations, dooming them to environmental catastrophe, and training them to create conflict and to view escalated violence as the solution to conflict is not a disease, what is?

The failure of any member of the United States Congress to take every possible step to block the spending of another dime on the so-called “homeland security” military aimed at the United States itself, or on the military aimed at the other 96% of humanity, is the most immoral failure that could be engaged in at this time.

- First published by World BEYOND War.

No comments:

Post a Comment