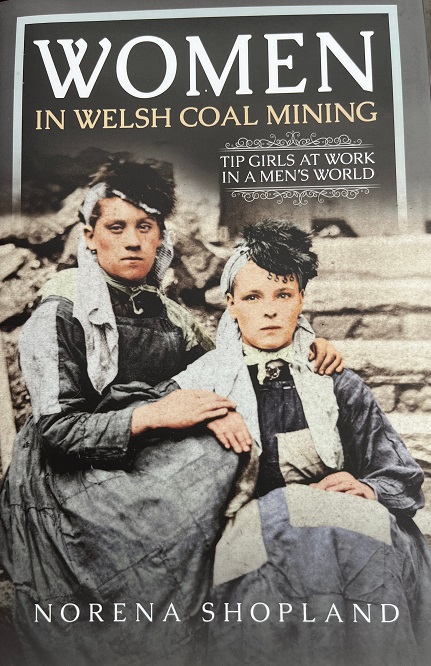

Women in Welsh Coal Mining

Norena Shopland

When 19-year-old Ann Bowcot from Dowlais was interviewed for the 1842 Children’s Employment report, she told the investigators that when she started work at the mines she was so small she had to be carried on her father’s shoulders to work.

She was not alone. It was common to see men carrying small children in the dark hours before dawn to the mine, where they would descend and remain most of the day.

Society was appalled, and demanded something be done.

The 1833 Factory Act had restricted the employment of children but why, people were asking, had this Act not been applied to other industries such as mining – so the government ordered an investigation.

As investigators studied the children, they were equally horrified to find women working underground close to men, in the dark, wearing little due to the heat and crowded space, smoking, swearing, and behaving like men, so the report was expanded to include women. The subsequent 1842 Act banned boys under ten and all females from working underground.

The ban however, did not start to take effect for several decades because there were so few inspectors that employers simply ignored the laws but finally, women were moved to the pit brow where they would pull and push the trams of coal, often the weight of a small car, off the pit head, empty it, break up large chunks of coal, clean and pack it ready for sale.

Other jobs included sweeping the roads of constant dust, or oiling trams that needed to be tipped over to get to the wheels and could result in injuries or death.

Grime

The Tip Girls as they were familiarly known in Wales, were covered in dust and grime, so for a touch of individuality they would wear colourful head scarfs to keep the dust from their hair or, a unique feature of the Welsh women, fancy hats decorated with feathers, buttons and bows and some even dared to wear trousers, something fiercely disapproved of by society.

Critics came out in force and, rather like those on social media today, felt emboldened to criticise tip girls calling them unsexed, hideous hermaphrodites, or immoral and that they should get back to being domestic servants or factory workers, despite few of these jobs available in the valleys of south Wales.

Nevertheless, the critics continued, particularly as the publicity had turned the tip girls into visitor attractions and journalists, authors, photographers, sketch artists, or tourists would turn up to talk to or simply stare at the women.

Eventually MPs started asking questions in the House of Commons as to whether females should be allowed to continue in what society (mostly men) deemed highly inappropriate work – hardly anyone asked the women what they wanted.

All these attitudes came to a head in 1886 when the government announced they were preparing a new Mines Bill and would once again, consider banning women working in the coal and iron industries – people began to take sides.

In April a large and ‘enthusiastic meeting of colliers, labourers, women, and girls, employed in and about collieries, was held at the Temperance-hall, Tredegar, to protest against the proposed abolition or female labour at the pit’s mouth.’

The South Wales Echo reporting that one of the speakers (no women were allowed to speak) remarked that ‘there is no question that the work done by women and girls at the pit’s mouth is far healthier, more moral, and in every way superior to the work in which thousands of women and children are employed in cotton and kindred factories.’

They highlighted the difficulties that would be faced by ‘the large mass of widows and others who were now engaged about the collieries in employment they had followed from their childhood …

No other door would be open to then; except to the workhouse.’ The motion to support the women was carried unanimously.

Mine owners

As many MPs were mine owners, or had shares in mines, they voted to allow women to carry on working as they were often paid a fraction of men’s wages, but the criticism continued.

The women continued to fight back.

In 1887, the Pit Brow Lasses of Lancashire, joined by women from other mining districts, decided to march on Westminster to appeal directly to the Home Secretary to leave them alone and let them work in peace.

They marched through the streets of London in their working costumes, gawped at by the crowds who watched them, and once again, no ban was forthcoming. But in 1911 they had to do it all again, and marched on Westminster begging to be left alone.

The situation limped along in this manner until the introduction of new machinery which cut the number of working women, but they persevered through the First World War until the last woman finished in 1966.

The last Welsh woman was possibly Martha Richards who died aged 93 in 1974, the last woman to have worked in the Stepaside Pits, Pembrokeshire.

Women moved to supportive roles, caring, catering, and administrative, and occasionally posed as wives and family members in photos amid hordes of men until the late twentieth century when UK laws lifted many restrictions on women’s employment – but gender employment and pay gaps persist.

Following the Employment Act 1989, women are now allowed to work underground, but few do so.

Now for the first time, these remarkable women’s stories are told in my book Women in Welsh Coal Mining: Tip Girls at work in a men’s world (Pen and Sword Books, 2023).

Although women in Welsh coal mining were in a minority compared to men, their work was vital and it is important that we celebrate them and their determination to withstand the constant, but unfounded and unfair criticism.

Women’s history still lags a long way behind that of men, so we must keep uncovering and writing about them because at the end of the day it is not women’s history, it is simply history.

You can buy Women in Welsh Coal Mining: Tip Girls at work in a men’s world here…….

No comments:

Post a Comment