Closing Nuclear Reactors Means Big Improvements in Local Infant Health

Aerial view of the Consumers Power Company of Michigan’s Palisades Plant Unit 1. Photo: Department of Energy.

Not long ago, the U.S. nuclear power industry was in freefall. Only two reactors had been ordered since 1978, meaning the existing reactors were aging. Old mechanical parts require costly maintenance; and rather than pay for these upgrades, nuclear plant owners chose to shut reactors (13 out of 104 in the U.S. closed from 2013-2022). Many more closings seemed imminent, as two-thirds of reactors had operated more than 40 years, the expected lifespan. The dream that nuclear power would dominate the U.S. electrical market with 1,200 reactors was ending.

But just recently, industry and government combined to postpone nuclear power’s sundown. State governments took the first step; legislatures in five states passed laws giving billions of dollars to bail out utilities, and keep old reactors operating. The federal government then passed the Inflation Reduction Act, which included pledges of up to $135 billion for keeping old reactors open, and supporting new ones.

The mantra of pro-nuclear forces was nuclear power was “green” and “emission-free” – and would address climate change. But that mantra is not based in fact. The processes of developing uranium for reactors (mining, milling, enrichment, fabrication, and purification) consume large amounts of greenhouse gases. And reactors are NOT “emission-free” as they routinely release over 100 highly toxic radioactive chemicals – the same found in atom bomb explosions – into the air and water.

Federal regulators helped keep the nuclear dream alive by rubber-stamping applications to extend licenses beyond the original 40 years. Currently, 12 reactors are approved to operate up to 80 years, and dozens more applications are expected. An 80-year-old reactor means staggering amounts of highly radioactive waste stored at each site, and the growing chance of a catastrophic meltdown.

Preserving antiquated reactors was the original focus of a nuclear revival. A never-attempted strategy to restart closed reactors has also surfaced. Proposed restarts include:

Palisades: Palisades, in western Michigan, closed in 2022 after 51 years; it only supplied 5% of the state’s electricity. But enormous (mostly federal) government pledges of support led Holtec International to apply for restart, which may be granted as soon as late 2025.

Three Mile Island: The largest U.S. reactor meltdown destroyed one of the plant’s reactors in 1979; its other unit closed in 2019 after 45 years. Constellation Energy recently signed an agreement to restart the reactor in 2028, to power Microsoft’s AI operations.

Duane Arnold: Iowa’s only reactor, which generated only 8% of the state’s electricity, closed in 2020 after 46 years. Several months ago, NextEra Energy filed a licensing change request to federal regulators, with a goal of restarting the plant in 2028.

Still another aspect of an envisioned nuclear revival focuses on building Small Modular Reactors. Proponents claim SMRs would be speedier to build, cheaper, more efficient, and cleaner than larger reactors of the past. But these claims are unproven, and proposed SMRs at several sites have thus far been scrapped due to spiraling cost estimates.

Discussion of nuclear power’s future has been mostly about costs. The 1954 prediction by federal official Lewis Strauss that nuclear reactors would produce energy “too cheap to meter” has failed miserably, as nuclear is now much more costly than wind, and solar power. The most crucial reactor issue – health hazards – has been largely ignored by industry and government.

Numerous articles and reports have documented rising rates of cancer near reactors (www.radiation.org). But recent reactor shutdowns and their proposed restart have raised another issue – does shutdown (and the end of routine radioactive exposures) mean improved health?

A 2002 journal article showed local infant deaths fell more sharply than the U.S. decline near eight closed nuclear plants two years after closing (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12071357/). Infants are more susceptible to radiation effects than adults, and any reduction in exposure after shutdown suggests health of infants would be most likely to improve.

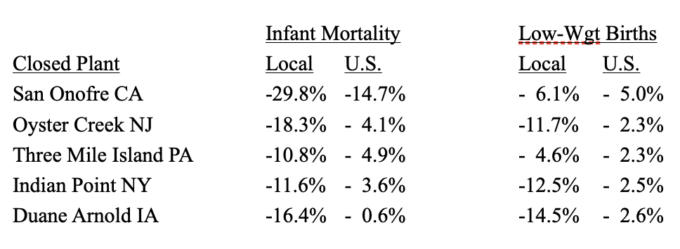

A review of CDC data updates this study for recently-closed plants, including some slated for restart. The table below shows the decline in infant death rates (< 1 year) and low-weight births under 3.3 pounds, in the five years before/after shutdown, for the local county(ies) and the U.S.

Near each closed plant, the local reduction was larger than the nation’s for both infant deaths and low-weight births. Some gaps are especially large, amounting to hundreds more healthy infants.

Palisades is the reactor in line to be the first to restart after permanent shutdown. In the last five years of operation (2018-2022), 15 babies of mothers living in Van Buren County MI, where the reactor is located, died. But in the 2½ years after, only four infants died, a decline of almost 50%.

Restart of closed reactors, or startup of new ones, must address health risks. Evidence of infant health improvements near closed reactors suggests no such actions be taken, and funds to prop up nuclear power instead be allotted for safe, renewable, less costly energy sources such as wind and solar.

A Bad Supreme Court Decision Paves the Way for Radioactive Waste Storage in the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico

Photograph Source: Sam Saunders from Bristol – CC BY-SA 2.0

The great problem with nuclear energy, hidden from the public as often as possible by the federal government and special interests, is the quantities of radioactive waste nuclear reactors produce.

Nearly 100,000 tons of spent nuclear fuel rods are stored at the sites of 92 open and 42 closed nuclear power plants in the country and about 2,000 tons a year are added to the piles. Plans for a permanent federal storage site at Yucca Mountain in Nevada are mired in controversy and effective opposition. Two private firms have proposed storage sites in the Permian Basin, one in Texas, the other 40 miles away in New Mexico. One sits directly on top of the Oglala Aquifer, which provides water for millions in eight states from South Dakota to west Texas and New Mexico; the other sits immediately adjacent to the aquifer. In plain language, the Nuclear Waste Policy Act allows storage of nuclear waste either at nuclear reactor sites or at sites owned by the federal government. Environmental groups believe there is a high probability that the federal government will change the designations from temporary to permanent sites after their 40-year licenses expire.

Ninety percent of nuclear reactors are in the eastern half of the nation; the two proposed sites would generate up to 10,000 trips by road, rail or waterway of highly radioactive cargo called by residents along their routes things like “Mobile Chornobyl,” “Floating Fukushima,” “Dirty Bomb on Wheels,” and “Mobile X-ray Machine That Can’t Be Turned Off.”

In the words of Haul No!, an indigenous group based in Albuquerque, “The Southwest is under attack! Nuclear colonialism, via this push for new development of both energy and weapons, is threatening our communities…”

The U.S. Supreme Court decided on June 18 that the Texas storage project, presented as a temporary site, could receive nuclear reactor waste despite the language of the federal nuclear waste act. This decision paves the way for the further development of the New Mexico site.

The state of Texas and a large Permian Basin landowner had sued the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and the NRC appealed the federal Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision in favor of the state. Six justices, Kavanaugh, Roberts, Sotomayor, Kagan, Barrett, and Jackson voted to reverse the appeals court’s decision; Gorsuch, Alito, and Thomas dissented.

Associate Justice Kavanaugh wrote the majority opinion, arguing that Texas and the landowner lacked standing to bring the suit, ignoring entirely the substance of the case, whether nuclear waste could be stored on a privately owned site against the words and meaning of the act.

Associate Justice Gorsuch, son of Reagan Era EPA Administrator Anne Gorsuch, argued at length and cogently that these sites violated the law and were environmentally dangerous.

Kevin Kamps, Beyond Nuclear’s radioactive waste specialist, said: “Even though SCOTUS has upheld the NRC license for ISP’s dump, we still hope to stop it, and Holtec’s dump as well, from going forward. After all, we were previously able to stop a very similar dump of Holtec’s and the nuclear power industry’s from going forward in Utah, on the Skull Valley Goshutes Indian Reservation, despite NRC having licensed it, and the federal courts having upheld that NRC license as well.”

Beyond Nuclear also announced that it would continue legal action against the New Mexico site: “We have raised the right issues in the right court,” said Diane Curran, co-counsel for Beyond Nuclear. “We look forward to resuming our litigation in the D.C. Circuit, where we will demonstrate that the law unequivocally prohibits Holtec’s private storage of federally owned spent fuel.”

Both Elan Musk’s DOGE boys and Trump’s executive orders this year have significantly weakened the NRC’s ability to function effectively. These actions are part of a campaign that began several years ago to reopen and develop new uranium mines on the Colorado Plateau, reopen and develop new uranium processing mills in the West, successful legislation to make it illegal for nuclear reactor operators to buy Russian uranium processed for reactor use, and a new generation of nuclear warheads, among other developments in the nuclear industry. But staff damage can be repaired by later administrations and executive orders can be fought in court or reversed by later administrations.

No comments:

Post a Comment