Military aid for Ukraine falls despite new Nato PURL initiative – Statista

As European policy makers and defence industry leaders came together on October 13 to discuss current and upcoming challenges at the fifth European Defence & Security Conference in Brussels, the Kiel Institute for the World Economy published the latest update of its Ukraine Support Tracker, Statista reports.

The researchers, who have been tracking aid to Ukraine since Russia’s invasion in February 2022, found that military aid to Ukraine dropped sharply in July and August compared to previous months, despite the implementation of the Nato PURL (Prioritized Ukraine Requirements List) initiative.

The program, devised by Nato Secretary General Mark Rutte and US President Donald Trump in July, enables Nato allies to fund the acquisition of “ready-to-use” weapons from US stockpiles for Ukraine, potentially fast-tracking the supply of urgently needed military equipment to the country. By August, eight Nato countries, namely Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Latvia, the Netherlands and Sweden had made use of the new mechanism, providing a total of €1.9bn in funding. And yet, total military aid to Ukraine declined significantly in July and August, falling 43% compared to the monthly average in the first six months of 2025.

In the first half of 2025, Europe had ramped up its contributions significantly to make up for the suspension of US military aid. This momentum didn’t carry into July and August, however, when European aid fell more than 50%, even when accounting for Europe’s contributions to the Nato PURL program. “The decline in military aid in July and August is surprising,” Christoph Trebesch, head of the Ukraine Support Tracker and Research Director at the Kiel Institute, said in a statement. “The overall level of financial and humanitarian support has remained comparatively stable – even in the absence of US contributions,” Trebesch noted. “It is now crucial that this stability extends to military support as well, as Ukraine relies on it to sustain its defence efforts on the ground.”

The US cannot deplete its own stockpile of Tomahawk cruise missiles by supplying them to Ukraine, President Donald Trump said at a press conference on October 16 following a phone conversation with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

"We need Tomahawks for the US too. We have a lot of them, but we need them," he said, reports TASS.

"I mean, we can't deplete our country. So, you know, they're very vital, they're very powerful, they're very accurate, they're very good, but we need them too, so I don't know what we can do about that," Trump added.

He also confirmed that he would meet with Putin in Budapest next week for a second face-to-face meeting.

The remarks come amid renewed pressure from Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy for Washington to authorise the transfer of Tomahawk missiles and boost deliveries of air defence munitions including Patriot air defence systems. Trump, however, indicated that any such decision would require further consultation with Moscow.

“I did actually say, “Would you mind if I gave a couple of 1,000 Tomahawks to your opposition?” I did say that to him. I said it just that way,” Trump said sarcastically when asked whether Putin had objected to the potential transfer. “What do you think he's going to say? “Please sell Tomahawks”?”

Trump described the missiles as “a vicious, offensive, incredibly destructive weapon,” adding: “Nobody wants Tomahawk shot at him.”

Putin, for his part, has warned that the deployment of Tomahawks in Ukraine would mark a dangerous escalation.

“They cannot be used without the direct involvement of US military personnel,” he said, according to TASS, cautioning that such a move would represent “a qualitatively new phase of escalation, including in relations between Russia and the United States.”

The Kremlin has gone further, stating that any launch of a Tomahawk missile toward Russian territory would be treated as a potential nuclear first strike, given that the cruise missiles are capable of carrying nuclear warheads and it would be “impossible to determine” the payload in flight. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said Russia would respond “accordingly” if such missiles were supplied to Ukraine.

Trump also signalled a pause in the imposition of new sanctions on Russia at the press conference. Although legislation to target Russian energy exports and other key sectors has been drafted and awaits Senate approval, the president indicated it would not move forward in the immediate term.

"I'm not against anything. I'm just saying, it may not be perfect timing," Trump said.

Despite repeatedly stating he would increase pressure on the Kremlin, Trump has yet to authorise any new sanctions in Russia since taking office. At the same time the US has sent no money and the delivery of US weapons to Ukraine has fallen to nothing in the last few months.

Ukraine shifts tactics amid aid uncertainty

Over the last months Ukraine has changed tactics and has been targeting Russian refineries, reducing production by between 10%-30% according to analyst estimates and causing a fuel crisis in Russia.

Ukraine has been using its improved long-range drones and has developed its own Flamingo cruise missile but is desperate for more and more powerful missiles to increase the damage.

“In fact, our strikes have had a greater impact than the sanctions. That's just mathematical truth,” said Kyrylo Budanov, head of Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence, speaking at the Kyiv International Economic Forum on October 16.

“We have inflicted far more direct damage to the Russian Federation's profits than any economic measures imposed so far.” Budanov said Ukraine’s long-range capabilities now rely almost entirely on domestic production, adding: “Of course, we always want more, but it exists. It's our domestic production that has allowed us to use our forces and means in the way we see fit.”

The fall in oil revenues has already impacted the Russian budget and sent the budget deficit soaring, but as bne IntelliNews reported, Ukraine’s budget is in equal trouble as Europe scrambles to find some $65bn to finance Ukraine’s war through to 2026.

However, Budanov warned that without further sanctions or external pressure, Moscow can sustain its war effort “for quite a long time.”

Trump and Putin plan talks in Hungary

Trump also announced plans to meet Vladimir Putin in Budapest, Hungary, to discuss efforts to end the war in Ukraine, a second meeting following the Alaska summit on August 15.

“At the conclusion of the call, we agreed that there will be a meeting of our High Level Advisors, next week,” Trump posted on Truth Social. “A meeting location is to be determined. President Putin and I will then meet in an agreed upon location, Budapest, Hungary, to see if we can bring this “inglorious” war, between Russia and Ukraine, to an end.” Trump said that Secretary of State Marco Rubio would lead the initial US delegation.

Hungary, a Nato member led by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, has drawn criticism from EU allies for its stance on Russia and democratic backsliding. Orbán is seen as a key ally of Trump and a possible host for the proposed summit.

Both the Kremlin and the Trump administration have admitted that the two presidents discussed more than just the war in Ukraine during their meeting in Anchorage. bne IntelliNews sources in Washington say that various business deals are on the table and Trump has made it clear from the start that he is interested in doing business with Russia.

The details of the various deals remains unclear, but is known to include allowing ExxonMobil back into the Sakhalin-1 oil project and the joint exploration and exploitation of various critical minerals and rare earth metals (REMs) deposits. The possibility of lifting some aviation sanctions was also discussed that would allow Boeing to restart the sale of parts for the Russian fleet to resume in return for giving the US access to Russia’s virtual monopoly over titanium production – an essential input for plane-makers.

Indeed, as bne IntelliNews reported, Trump’s entire foreign policy is driven by a minerals diplomacy where he has attempted to tie access to minerals to almost all the peace deals he has cut in the last nine months in an attempt to break China’s monopoly over the sector. In this drive, Russia is the big prize as it is home to a cornucopia of raw materials, second only to those found in China.

Trump confirmed that he would also meet President Zelenskiy at the White House on October 17. “President Zelenskiy and I will be meeting tomorrow, in the Oval Office, where we will discuss my conversation with President Putin, and much more,” he said. “I believe great progress was made with today’s telephone conversation.”

Trump downplays hopes he will supply Ukraine with Tomahawks in talks with Zelensky

US President Donald Trump said Friday it was likely too soon to send Tomahawk missiles to Ukraine, suggesting the war with Russia could end without them, as he met President Volodymyr Zelensky at the White House a day after agreeing to a new summit with Vladimir Putin.

Issued on: 17/10/2025

By:

FRANCE 24

Video by:

Monte FRANCIS

01:44

Zelensky, who came to the White House to push for the long-range US-made weapons, said however that he would be ready to swap "thousands" of Ukrainian drones in exchange for Tomahawks.

The US president's reluctant stance came a day after he and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed in a call to hold a new summit in the Hungarian capital Budapest.

Watch more The Debate: The Tomahawks are coming?

"Hopefully we'll be able to get the war over with without thinking about Tomahawks," Trump told journalists including an AFP reporter as the two leaders met at the White House.

Supplying Ukraine with the powerful missiles despite Putin's warnings against doing so "could mean big escalation. It could mean a lot of bad things can happen."

Trump added that he believed Putin, whom he met in Alaska in August in a summit that failed to produce a breakthrough, "wants to end the war".

Tomahawks for Ukraine: Game changing weapon or leverage over Moscow?

Fresh off the Gaza ceasefire deal, Donald Trump is about to meet with Volodymyr Zelenskyy to discuss the possibility of selling Tomahawk missiles to Ukraine. Both Washington and Kyiv believe it may bring Vladimir Putin to the negotiating table.

Russia has again ramped up its attacks on Ukraine’s energy grid as the weather became noticeably colder, just as Moscow did every autumn since its full-scale invasion in February 2022.

Although Ukraine’s air defence has improved significantly and is now capable of intercepting most of the deadly drones Russia launches daily in droves, Kyiv is hoping for something beyond the additional support it requested from partners.

Ukraine has asked for something strategically crucial to its goals: long-range missiles to strike Russia’s launching pads instead of remaining limited to intercepting hundreds of drones and tens of missiles once they already reach Ukrainian skies.

Fresh off the Gaza ceasefire deal, US President Donald Trump suggested on Tuesday that he might allow the sale of Tomahawk missiles to Ukraine. They would give Kyiv the ability to hit deeper into Russia’s rear and make those strikes more powerful and precise.

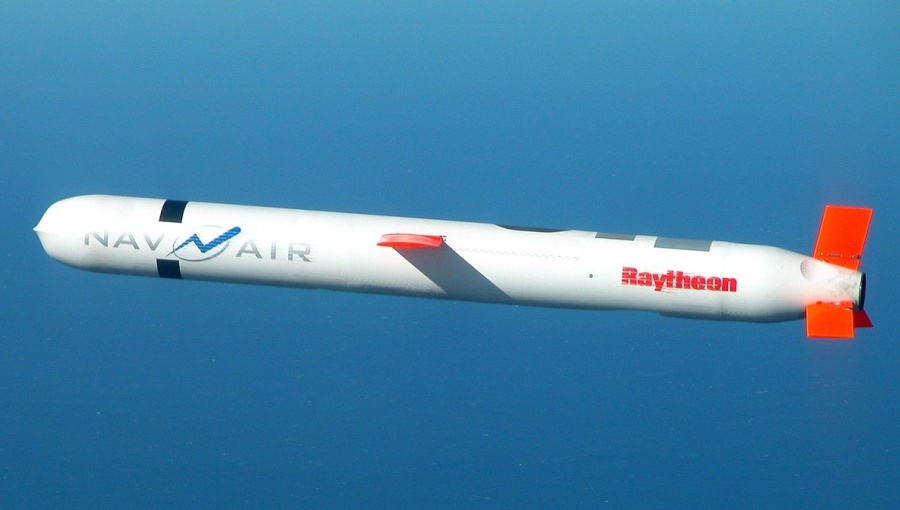

A key part of the US arsenal, Tomahawk missiles have an operational range of 1,600 to 2,500 kilometres and a powerful warhead weighing 400 to 450 kilograms. For the moment, Ukraine relies on Western-supplied missiles, such as Storm Shadow, which have a limited range of about 250 kilometres.

For anything beyond this, Kyiv is utilising its domestically produced drones and drone-like missiles, such as the Palianytsia, but their warhead payload is restricted to 50-100 kilograms.

As Trump and his Ukrainian counterpart Volodymyr Zelenskyy prepare to meet in Washington on Friday, the issue of Tomahawks is high on the agenda, if not at the top.

“He would like to have Tomahawks,” Trump said of Zelenskyy. “We have a lot of Tomahawks.”

Euronews sources among Ukrainian officials said Kyiv is doing its best to outline to Washington why it needs Tomahawk missiles, what long-range weapons the country already has, and what Ukraine is lacking, and that this will be discussed at the White House on Friday.

'Their tech is saving lives'

The Ukrainian delegation is already in the US ahead of the Trump-Zelenskyy meeting.

Head of Zelenskyy’s office, Andriy Yermak, together with the Prime Minister, Yulia Svyrydenko, and other Ukrainian officials, has met the US defence companies Lockheed Martin and Raytheon.

Raytheon is the producer of Tomahawk missiles.

“Their tech is saving lives: F-16s and advanced air defence systems are shielding Ukrainian skies”, Yermak said in a post on X. "Their offensive solutions strongly support our forces on the frontline,” he added.

Without mentioning Tomahawk missiles, Yermak said this cooperation with Ukraine keeps growing.

“Each downed Russian missile or destroyed enemy command post proves the quality of US weapons and the professionalism of our troops,” he explained.

The US-based Institute for the Study of War think tank (ISW) has assessed that there are at least 1,945 Russian military facilities within range of the 2,500-kilometre variant Tomahawk and at least 1,655 within range of the 1,600-kilometre variant.

“Ukraine likely can significantly degrade Russia’s frontline battlefield performance by targeting a vulnerable subset of rear support areas that sustain and support Russia’s frontline operations,” the ISW analysis said.

Trump’s leverage over Moscow

The possibility of Ukraine getting Tomahawk missiles triggered worry and sabre-rattling from Moscow.

The Kremlin said it is causing “extreme concern” in Russia, adding that the war is entering what spokeseperson Dmitry Peskov called a “dramatic moment in terms of the fact that tensions are escalating from all sides.”

Former Russian President Dmitry Medvedev threatened the US and Trump personally with a nuclear response.

“It’s been said a hundred times, in a manner understandable even to the star-spangled man, that it’s impossible to distinguish a nuclear Tomahawk missile from a conventional one in flight," Medvedev said.

“The delivery of these missiles could end badly for everyone. And most of all, for Trump himself.”

But for Trump, there is one more critical aspect regarding the possibility of sending Tomahawk missiles to Ukraine.

Euronews sources among Ukrainian officials confirmed that Kyiv's argument to convince the White House to send Tomahawk missiles is that they remain game changers and among the most important levers of influence on Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The US president suggested over the past several days that the mere threat of this could force Putin to the negotiating table. Trump also said he planned to talk directly with the Russian president about the subject.

“If this war doesn’t get settled, I may send Tomahawks,” Trump said.

“A Tomahawk is an incredible weapon. And Russia does not need that. If the war is not settled, we may do it. We may not. But we may do it.”

Zelensky congratulated Trump on his recent Middle East peace deal in Gaza and said he hoped he would do the same for Ukraine. "I hope that President Trump can manage it," he said.

Ukraine has been lobbying Washington for Tomahawks for weeks, arguing that the missiles could help put pressure on Russia to end its brutal three-and-a-half year invasion.

Zelensky, meeting Trump in Washington for the third time since the US president's return to power, suggested that "the United States has Tomahawks and other missiles, very strong missiles, but they can have our 1,000s of drones."

Kyiv has made extensive use of drones since Russia invaded in February 2022.

On the eve of Zelensky's visit, Putin warned Trump in their call against delivering the weapons, saying it could escalate the war and jeopardise peace talks.

Trump said the United States had to be careful to not "deplete" its own supplies of Tomahawks, which have a range of over 1,600 kilometres (1,000 miles).

Diplomatic talks on ending Russia's invasion have stalled since the Alaska summit.

The Kremlin said Friday that "many questions" needed resolving before Putin and Trump could meet, including who would be on each negotiating team.

But it brushed off suggestions Putin would have difficulty flying over European airspace.

Hungary said it would ensure Putin could enter and "hold successful talks" with the US despite an International Criminal Court (ICC) arrest warrant against him for alleged war crimes.

Trump frustrations

Since the start of his second term, Trump's position on the Ukraine war has shifted dramatically back and forth.

Initially Trump and Putin reached out to each other as the US leader derided Zelensky as a "dictator without elections".

Tensions came to a head in February, when Trump accused his Ukrainian counterpart of "not having the cards" in a rancorous televised meeting at the Oval Office.

Relations between the two have since warmed as Trump has expressed growing frustration with Putin.

But Trump has kept a channel of dialogue open with Putin, saying that they "get along".

The US leader has repeatedly changed his position on sanctions and other steps against Russia following calls with the Russian president.

Putin ordered a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, describing it as a "special military operation" to demilitarise the country and prevent the expansion of NATO.

Kyiv and its European allies say the war is an illegal land grab that has resulted in tens of thousands of civilian and military casualties and widespread destruction.

Russia now occupies around a fifth of Ukrainian territory – much of it ravaged by fighting. On Friday the Russian defence ministry announced it had captured three villages in Ukraine's Dnipropetrovsk and Kharkiv regions.

(FRANCE 24 with AFP)

American Missiles And Russian Dachas: Tomahawk And The Future Of Stability And Deterrence In Europe – Analysis

A tomahawk cruise missile launches from the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Shoup.

October 18, 2025

Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Aaron Stein and Sam Lair

(FPRI) — The Tomahawk cruise missile is a near perfect machine. Its development followed advances in guidance and turbofan engine technology in the 1970s. It has been tested for decades. And it has been upgraded and augmented for the same amount of time. The missile’s accuracy has always been a source of concern in Moscow, where its deployment in Europe in a ground-launched variant in the 1980s helped spur agreement on the elimination of this class of weapons, only for the erosion of arms control to once again be deployed within ground launch range of Russian targets.

A former Soviet Premier put it best in the days before the Cuban Missile Crisis. In response to the deployment of Jupiter missiles in Turkey, Nikita Khrushchev complained on a trip to the Black Sea that “[He] could see US missiles in Turkey aimed at [his] dacha.”

Soviet and then Russian fears about American encirclement are as old as the missile age. The major concern, as Khrushchev so elegantly put it, is that the United States can put a missile through the window of a Russian dacha in 10 minutes or less. These concerns were first centered on fears of a nuclear first strike, but with changes to both US doctrine and technology over the past 40-years, are now centered on American conventional overmatch: the idea that a US first strike could be aimed at the Russian leadership and, with continued advances in missile defense and precision strike, could eventually be used to negate Russia’s nuclear deterrent.

President Vladimir Putin cautioned against such missile deployments before his invasion of Ukraine in 2022. In November 2021, he warned “If some kind of strike systems appear on the territory of Ukraine, the flight time to Moscow will be 7-10 minutes …” If this sounds familiar, it is because it is the same argument Khrushchev made more than four decades ago. And it is the same argument Russian leaders are now making about the potential introduction of Tomahawk cruise missiles into Ukraine.

There are ample reasons for the United States to provide Ukraine with longer-range weapons. Russia is using its advantage in these longer-range systems to punish Kyiv and Ukrainian infrastructure. Ukraine is not winning the war. It is in a defensive position along the front and, therefore, lacks leverage over Moscow in any future negotiation for a favorable ceasefire. However, it would be unwise to summarily dismiss Russian concerns about Tomahawk or to assume, as President Donald Trump has suggested, that Moscow is a “paper tiger.

It is not. The Russian leadership has probed NATO’s eastern defenses with drones to some tactical success. It has the capability to strike targets anywhere in Europe. It has chosen not to because it has been deterred. Regardless, it is worth taking Russian leaders at their word about concerns over decapitation strikes. We think they really are afraid. While the risk of conflict spilling over the border remains low, any such move that crosses a stated Russian red line requires some deliberation. It also requires thinking how Moscow may react, and then doing things proactively to defend NATO’s exposed and porous eastern front from an inevitable Russian reaction to the introduction of Tomahawk.

A good way to think about this is to revisit the 1980s. There was a time when the United States had Tomahawk in Europe, and used the deployment of this weapon and others to reach agreement with the Soviet Union on their elimination.

Revisiting Euromissiles and Ground Launched Missiles in Europe

Russian opposition to the deployment of ground-launched Tomahawk missiles in Europe has deep roots, grounded in the fear of decapitation strikes against leadership. During the Euromissile crisis of the late 1970s and early 1980s, the deployment of nuclear-armed American Pershing-II ballistic missile and the Gryphon ground-launched variant of the Tomahawk caused profound consternation among Soviet leadership who worried about the short flight times in the European theater. The Pershing-II was a particular problem. It could reach Moscow in a handful of minutes. Soviet strategists also were concerned by the Gryphon’s mobility, difficulty of detection, and accuracy—a combination that made it ideal for a first strike weapon. While the Tomahawk was removed from the continent by the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, the missile continued to generate fear and uncertainty for Russian leaders. It can be launched from submarines and aircraft, preserving a key American advantage in fires that Moscow never really liked.

The issue of ground-launched Tomahawks reemerged during the Obama administration. It was part of the controversy over the European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA), a missile defense concept designed to defend European allies from a future long-range Iranian missile threat, beginning with deployments of Aegis guided-missile destroyers in the Mediterranean and culminating with the construction of Aegis Ashore missile defense sites in Romania and Poland. The MK-41 launch system is designed for multiple different missiles, including the Tomahawk. This makes perfect sense. The space on ships is limited. Therefore, you want a one size-fits-all approach to launching weapons. The EPAA simply moved much of that system ashore, MK-41 launcher and all.

Perhaps in an act of projection, Russian leaders have repeatedly suggested the United States could covertly redeploy long-range cruise missiles to Europe by arming the Aegis Ashore sites with Tomahawks. The MK-41 vertical launch system that the Aegis Ashore site would use to store and launch SM-3 interceptors could theoretically house Tomahawks, as both the SM-3 and the Tomahawk are launched out of the strike variant of the VLS launcher. However, the Aegis Ashore system lacks the requisite software, fire control hardware, and support equipment to plan and launch Tomahawk strikes. In 2022 the United States reportedly offered to allow Russia the opportunity to inspect Aegis Ashore sites to verify the absence of Tomahawks in the launchers.

Russia has always had an issue with the range restrictions in the INF Treaty. The agreement eliminated the missiles Moscow had once allotted to strike targets in Europe. Russia, in turn, sought ways to—at first—circumvent the agreement by testing the RS-26 to a range to comply with both the INF and New START treaties. It did so with a light payload. After declaring the road-mobile missile as New START compliant, Moscow swapped out the payload, decreasing the range, and giving its leaders the option to deploy what was (and is) a medium-range missile for targets in Europe. It is now using this missile, rechristened as Oreshnik, to strike Ukraine and to signal to Europe that it can use it to strike anywhere on the continent with either nuclear or conventional payloads.

The Russian military also just simply violated the INF treaty. They developed the SSC-8 Screwdriver/9M729 for the Iskander system. This is a ground-launched cruise missile, most probably modelled on the Kalibr missiles they deploy on both naval and long-range aviation platforms. Throughout this period, however, the Russian leadership remained preoccupied with the Aegis Ashore sites in Europe. Indeed, the ideal weapons to strike these sites in Europe is a medium-range missile.

The tensions over these missiles reached a crescendo in 2019. After years of hints and leaked reports about Russian INF violation, the United States began indicating it would withdraw from the INF treaty. In response, Putin gave a speech in which he stated the Aegis Ashore sites were “fit” for deploying Tomahawks that could reach Moscow in 10-12 minutes. Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov echoed those concerns about short flight times of INF-range cruise missiles in an interview. While the stationary Aegis Ashore sites mean such a capability wouldn’t be mobile, these comments indicate Russian leadership now saw the shorter flight times of cruise missiles launched from eastern Europe as an issue, exacerbating the longstanding Russian and Soviet concerns about the Tomahawk’s accuracy and ability to evade detection.

Moscow has sought to obscure their part in the INF treaty’s collapse. They intermittently offer to enter again into negotiations for a deployment moratorium, albeit without ever acknowledging that it was their decision-making that killed the agreement. This is a decision that they may come to regret. And it also raises a serious set of broader questions about strategic stability in Europe, which may become more salient if the Trump administration does indeed export Tomahawk to Ukraine and deploys similar systems in Europe (and in Asia with ranges that can hold targets in Russia at risk).

Russian Regret

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the specter of the Gryphon has returned for the Russian strategic planners. It has come in two forms, both carrying conventional warheads—a key difference from the Cold War.

The first is the US Army’s Typhon missile system. When the United States finally decided to abrogate the INF treaty in August of 2019, they did so by launching a Tomahawk from a MK-41 VLS cell on a trailer. This launcher was not originally a rigorously developed weapon system. The duct tape used to help strap the launcher on the trailer for the first test launch was clearly visible in photos released by the Department of Defense. Despite its rugged beginnings, the Army has built on the concept and produced Typhon—four MK-41 vertical launch cells carried in a 40-foot ISO container that launch the Tomahawk and the SM-6 ballistic missile. The mobile Typhon is also called the Mid-Range Capability and has been deployed for training exercises with American allies in the Philippines and Australia. The United States has decided to station an Army Multi-Domain Task Force in Wiesbaden, Germany. Starting in 2026, this will feature periodic deployments of a long-range fires capability, such as the Typhon system. Second, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has asked the United States for transfers of Tomahawk missiles to help repel the Russian invasion, a decision Trump is considering, according to Vice President J.D. Vance.

While the precise range of the Tomahawk depends on the variant and the flight path, such a transfer would give the Ukrainians a long-range precision strike option with enough range to target Moscow and much of the rest of European Russia. Keith Kellogg, the US special envoy to Ukraine, suggested that with the Tomahawk’s ability to hit deep into Russia, “There are no such things as sanctuaries,” hinting they could threaten leadership. Beyond the deployment of “destabilizing missile capabilities” which pose a “strategic threat” to their backyard, it is clear the Russians continue to worry INF range systems, including Tomahawks, could be used for decapitating strikes.

The Russian leadership may even see the conventional nature of the missiles being deployed to Germany and potentially Ukraine as lowering the threshold for such strikes. Nevertheless, it seems ground-launched Tomahawks are returning to Europe, carrying with them a host of dangers for the Russians. The deployment of US-operated missiles in Germany and, potentially, a different Tomahawk ground launcher in Ukraine is deeply ironic. Russia violated the INF treaty to gain advantages for prosecuting a hypothetical war in Europe. Those violations, however, eventually prompted a withdrawal and ushered in this new reality for the leadership in Moscow. The implications for strategic stability are a bit more difficult to discern. In some respects, the United States and NATO are simply matching a capability Moscow has developed and deployed. Yet, the potential to push that capability to the Russian border would be an outcome Moscow has sought to stop and dissuade for the duration of the war.

How might Russia respond? Various Russian officials have suggested a myriad of responses, ranging from increased hybrid attacks to striking the Polish airport where arms deliveries to Ukraine are collected for distribution. For much of the war, Russian threats have been empty. However, this red line may be one step too far. A direct attack on NATO is unlikely. Russia does not appear to have the appetite for conflict with a more powerful foe. The reality, of course, is that European NATO members—and the United States—have no appetite for war either. This is why Russia’s so-called “hybrid war” tactics can be so effective. They are provocative, yes, but not that provocative. They can prompt concern and anxiety in Europe. And Russia could then try and leverage fear to extract concessions, or split consensus about the future of Ukraine in Europe and North America.

It would be prudent to pair any such deployment with increased vigilance on NATO’s eastern front, perhaps increasing the capabilities of air and naval assets deployed as part of Baltic Sentry. Thinking beyond tactics, the return of missiles is certain to prompt anxiety in Russia. Deterrence has worked thus far in the conflict and is probably going to prevent direct confrontation between the world’s largest nuclear power and the world’s only nuclear-armed alliance. However, Tomahawk and missiles on Russian borders have always been a major irritant for the leadership in Moscow, so there are ample reasons to believe that any such deployment will ignite the Russian leadership’s anxiety about dying, prompting moves to make Europe pay a price for making Moscow’s elite uncomfortable.

About the authors:

Sam Lair is a Fellow in the National Security Program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI) and a Research Associate on the Open-Source Intelligence Team at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies.

Source: This article was published at FPRI

Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

Founded in 1955, FPRI (http://www.fpri.org/) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization devoted to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the development of policies that advance U.S. national interests and seeks to add perspective to events by fitting them into the larger historical and cultural context of internation

No comments:

Post a Comment