WASHINGTON (RNS) — Moments before the assault on the U.S. Capitol began Wednesday (Jan. 6), a mass of Trump supporters gathered at a northwest entrance. They were angry: Footage highlighted the presence of Proud Boys, an organization classified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, who were shouting one of their favorite chants: “F— Antifa!”

As throngs surged toward a barricade manned by a vastly outnumbered handful of police, a white flag appeared above the masses, flapping in the wind: It featured an ichthys — also known as a “Jesus fish” — painted with the colors of the American flag.

Above the symbol, the words: “Proud American Christian.”

It was one of several prominent examples of religious expression that occurred in and around the storming of the Capitol last week, which left five people dead — including a police officer. Before and even during the attack, insurrectionists appealed to faith as both a source of strength as well as justification for their assault on the seat of American democracy.

While not all participants were Christian, their rhetoric often reflected an aggressive, charismatic and hypermasculine form of Christian nationalism — a fusion of God and country that has lashed together disparate pieces of Donald Trump’s religious base.

“A mistake a lot of people have made over the past few years … is to suggest there is some fundamental conflict between evangelicalism and the kind of violence or threat of violence we’re seeing,” said Kristin Kobes Du Mez, a history professor at Calvin University and author of “Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation.”

“For decades now, evangelical devotional life, evangelical preaching and evangelical teaching has found a space to promote this kind of militancy.”

A form of this faith was on display in front of the Capitol the day before the attack, when hundreds of Trump supporters massed near the building for a “Jericho March.” The event’s name was a reference to the biblical account of Israelites besieging the city of Jericho in the Book of Joshua, a religious tale liberal religious activists have also invoked for their own events.

Women blow shofars during the Jericho March on Jan. 5, 2021, in Washington. RNS photo by Jack Jenkins

Trump supporters who gathered in Washington for the Jericho March were encouraged to march around the Capitol, shouting and blowing shofars as a protest against the 2020 presidential election results.

“This is our moment, Lord, this is our moment to take our country back,” declared one woman standing in a prayer circle near the U.S. Supreme Court. “This is our moment to fight … with you as our weapon. You are our fighter.”

A few minutes later, someone could be heard chanting a few feet away: “We fight for God, and God fights for us!”

With other pro-Trump gatherings taking place in the same area, the Jericho March felt less like a distinct event and more like one stage within a larger festival. Jericho March organizers encouraged participants to attend other “Stop the Steal” events, and those in Washington often did not draw firm distinctions between themselves and other Trump supporters.

“There were a bunch of agendas I followed to see how to get here,” said another woman who helped lead the prayer circle.

Some in the crowd left to march around the Capitol — an act others would repeat the day of that attack — following a woman waving a white flag emblazoned with a tree and the slogan “An Appeal To Heaven.” The flag has become a banner for Christian nationalism: First waved during the American Revolution, it is said to be a reference to an argument by British philosopher John Locke, who suggested that — just as the biblical figure Jephthah led the Israelites in battle against Ammon — so too do individuals retain the right to “appeal to heaven” and wage revolution.

Andrew Whitehead, co-author of the book “Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States,” argued such appeals are commonplace in evangelical circles.

“Christian nationalism really tends to draw on kind of an Old Testament narrative, a kind of blood purity and violence where the Christian nation needs to be defended against the outsiders,” Whitehead said, pointing to similar conclusions drawn by Yale sociologist Philip Gorski. “It really is identity-based and tribal, where there’s an us-versus-them.”

Indeed, antagonistic religious imagery was easy to spot at the Capitol raid the next day. One insurrectionist photographed in the building’s rotunda wore military fatigues with a patch on the shoulder that showcased a cross and the words “Armor of God.” Just below was another patch featuring a slogan wrapped around a stylized skull used by the comic book character The Punisher: “God will judge our enemies. We’ll arrange the meeting.”

A Trump supporter carries a Bible outside the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, in Washington. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

One person who claimed to have been among the attackers, 36-year-old West Texas florist Jenny Cudd, posted a video on Facebook discussing how she “charged the Capitol with patriots,” exclaiming “f— yes I’m proud of my actions.” She boasted about “break(ing) down” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office door, and praised other insurrectionists who attempted to overrun state capitols elsewhere.

She concluded her more than 20-minute video with an outline of her religious beliefs.

“To me, God and country are tied — to me they’re one and the same,” she said. “We were founded as a Christian country. And we see how far we have come from that. … We are a godly country, and we are founded on godly principles. And if we do not have our country, nothing else matters.”

Whitehead was shocked by the video, but not surprised. He said Cudd’s explicit fusion of God, country and Trump is a “perfect” example of Christian nationalism, but those who invoked it while storming the Capitol are but an extremist subset of a much larger group — one that doesn’t stop at the boundaries of evangelicalism.

“A little over half of Americans are favorable toward Christian nationalism to some extent,” Whitehead said. “Extremism of any form, whether it’s religious or not, can only really flourish if it’s allowed to. So with 50% of Americans being relatively favorable toward understanding the U.S. as a Christian nation, or even that Christianity should be favored, it creates a situation where those that want to take that view even further can do that.”

There are some evangelicals who are already condemning the faith expressions seen on Capitol Hill. Hundreds of faculty and staff at Wheaton College, an evangelical school, have signed a statement decrying the “blasphemous abuses of Christian symbols” during the attack. In addition, Russell Moore, head of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Center, said the displays reminded him of a “darker reality” at work.

“We can see it in Europe, with neo-Nazis of all stripes carrying crosses as signs of ‘European heritage’ and ‘the triumph of the West,’ and we can see it in these violent white nationalist movements such as those attacking our Capitol,” he told Religion News Service. “The god of QAnon and the Proud Boys and their fellow travelers is not the God of Jesus Christ but the ancient serpent of Eden, which Jesus called ‘a murderer from the beginning.’ The way of Jesus Christ is a very different way from that one.”

But evangelicalism is a tree with many branches. Anthea Butler, associate professor of religion at the University of Pennsylvania, pointed to Jenna Ryan, a real estate broker from Frisco, Texas. Ryan drew widespread attention for posting images of herself on social media next to a broken window at the Capitol with the caption: “If the news doesn’t stop lying about us we’re going to come after their studios next.”

Demonstrators break TV equipment outside the the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, in Washington. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

According to video obtained by The Daily Mail, Ryan also livestreamed herself as she entered the Capitol with other insurrectionists. As she crossed the threshold, she can be heard declaring “Here we are, in the name of Jesus! In the name above all names!”

Butler argued that the orisons of Ryan — who has since released a statement insisting she opposes the violence at the Capitol — are emblematic of Pentecostal or charismatic Christianity, which is both a part of evangelicalism and distinct in important ways. But recent years have seen such distinctions blur: Many of Trump’s faith advisers, such as Florida pastor Paula White, hail from charismatic traditions that place an emphasis on prophecy and “spiritual warfare.”

“To say ‘in the name of Jesus’ — that’s calling protection, but it’s also calling power,” Butler said. “So in other words, ‘Jesus has given us the power to bust into the Capitol.’”

A unsettling appeal to the Almighty was even heard during the attack: According to The Washington Post, when staffers who work for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell barricaded themselves in a room to hide from the rampaging mob, they could hear a woman praying loudly outside the door for “the evil of Congress to be brought to an end.”

Butler said such expressions could be traced back to politicized forms of evangelicalism that started under Billy Graham, but took a turn around 2008 — when that year’s Republican presidential nominee, John McCain, chose evangelical Christian Sarah Palin as his running mate. Over the next few years, multiple versions of faith-fueled politics began to emerge, some feuding with each other.

It was Trump who drew them back together, and loyalty to the president was paramount last week. In another video posted on Twitter, a man near the South side of the Capitol can be seen speaking to onlookers as hundreds stand atop the Capitol steps. While two Christian flags — white banners with a Red Cross in the corner — waved in front of him, he can be heard saying: “Donald Trump coordinated it. We’re his surrogates. He fought for us and we have to fight for him.”

He then glances at the flags before adding what sounds like “Jesus loves us.”

Du Mez said this kind of reverence for Trump is rooted in a similar affinity for masculinity that permeates many religious traditions, including evangelicalism.

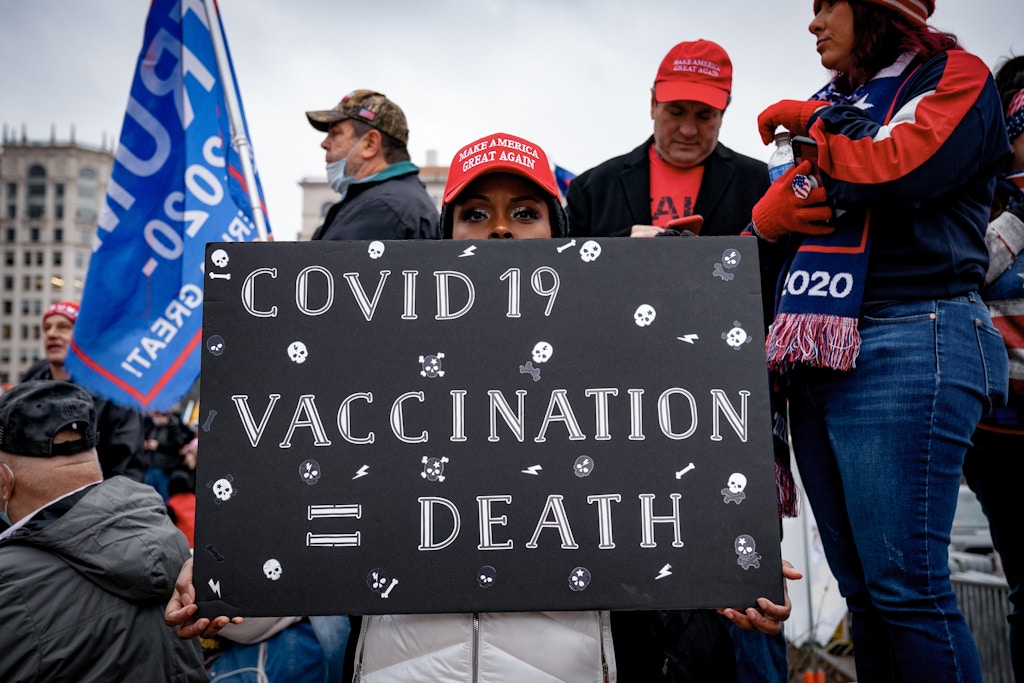

Trump supporters try to break through a police barrier Jan. 6, 2021, at the Capitol in Washington. As Congress prepared to affirm President-elect Joe Biden’s victory, thousands of people gathered to show their support for President Donald Trump and his claims of election fraud. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez)

“In the the last five years, we’ve seen this God and country nationalism coalesce around the figure of Donald Trump,” Du Mez said. “There were a variety of paths to get to this point, but it coalesced in part around this long-standing us-versus-them mentality, this persecution complex, this sense that white evangelicals were particularly vulnerable and therefore needed to not just defend themselves, but that the best defense is a good offense.”

Trump, she said, “is really the perfect figure to stoke these anxieties, to promise to be their strong man, to be their protector. … He’s God’s special defender that God has blessed the country with for this perilous moment.”

All scholars who spoke to RNS said Christian nationalism and hypermasculinity often overlap with forms of white supremacy. Proud Boys leader Enrique Tarrio, for instance, was arrested earlier last week after he and members of his group tore a Black Lives Matter sign from a Washington church in December and burned it in the street. But the Proud Boys who appeared in Washington on Wednesday insisted they drew strength from God: As they approached the Capitol, Proud Boys — some donned in camouflage or military-style helmets, others gripping weapons such as a baseball bat — paused for a moment of prayer.

As they knelt, a man with a bullhorn — his words captured on a livestream — prayed that God would “soften the hearts” of government officials who have “turned harshly away” from God, asking for “reformation and revival.”

He concluded: “We pray that you provide all of us with courage and strength to both represent you and represent our culture well.”

For Du Mez, the prayer was striking precisely because of how normal it seemed.

“It was an evangelical prayer,” she said. “It seemed perfectly natural to all of the Proud Boys in that circle to hear that prayer and to respond. It really signals this enmeshment of white nationalism, violence and a kind of ordinary white evangelicalism.”

Whitehead agreed, and warned that ignoring such dynamics can have dire consequences.

“Christian nationalism really is a threat to pluralistic democratic society, and everybody should take that threat seriously,” he said. “We’ve seen what happens where there’s no proof of voter fraud, yet people go and — under the guise of Christian symbols and symbolism — enact violence against their own country.”

‘

‘