HYDROCARBONS A SUNSET INDUSTRY

Big Oil hits brakes on search for new fossil fuels

© Reuters/Christian Hartmann FILE PHOTO:

The sun sets behind a pump-jack outside Saint-Fiacre

LONDON (Reuters) - Top oil and gas companies sharply slowed their search for new fossil fuel resources last year, data shows, as lower energy prices due to the coronavirus crisis triggered spending cuts.

Acquisitions of new onshore and offshore exploration licences for the top five Western energy giants dropped to the lowest in at least five years, data from Oslo-based consultancy Rystad Energy showed.

The number of exploration licensing rounds dropped last year due to the epidemic while companies including Exxon Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell and France's Total also reduced spending, Rystad Energy analyst Palzor Shenga said.

"Acquiring additional leases comes with a cost and it demands some work commitments to be fulfilled. Hence, companies would not want to pile up on additional acreages in their non-core areas of operations," Shenga said.

LONDON (Reuters) - Top oil and gas companies sharply slowed their search for new fossil fuel resources last year, data shows, as lower energy prices due to the coronavirus crisis triggered spending cuts.

Acquisitions of new onshore and offshore exploration licences for the top five Western energy giants dropped to the lowest in at least five years, data from Oslo-based consultancy Rystad Energy showed.

The number of exploration licensing rounds dropped last year due to the epidemic while companies including Exxon Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell and France's Total also reduced spending, Rystad Energy analyst Palzor Shenga said.

"Acquiring additional leases comes with a cost and it demands some work commitments to be fulfilled. Hence, companies would not want to pile up on additional acreages in their non-core areas of operations," Shenga said.

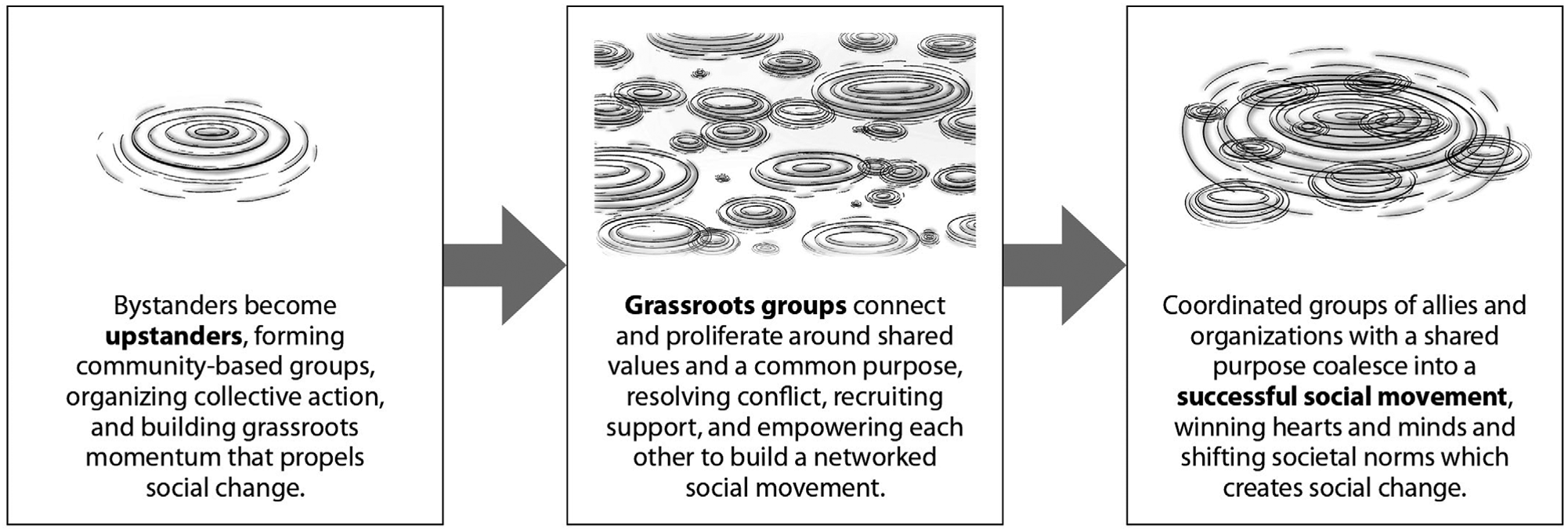

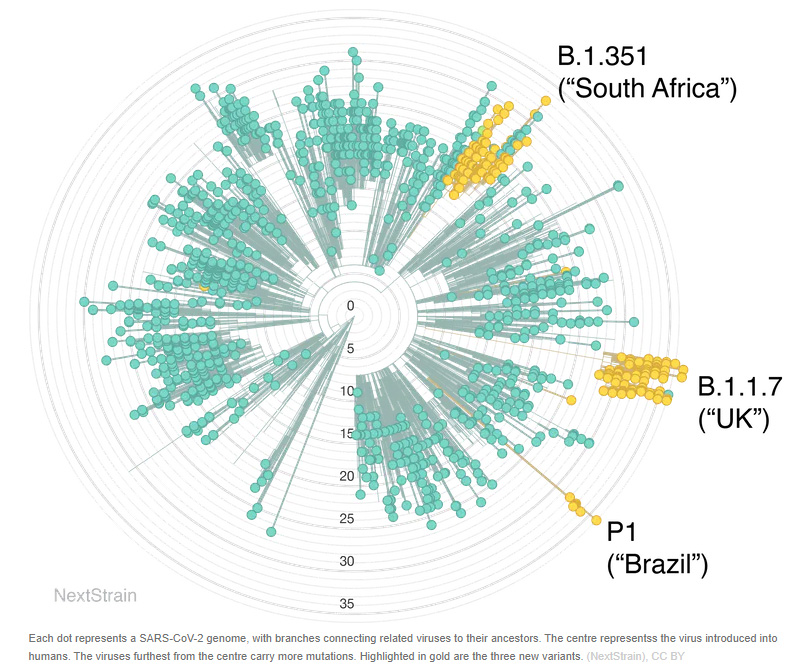

Slowing exploration

Oil majors sharply slowed down acquisitions of oil and gas exploration acreage in 2020

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

X

6636

11666

ExxonMobil

7049

60859

16780

62297

17012

18447

Total

15201

33983

22084

60758

16912

14480

Eni

6952

63950

12128

35094

11434

11730

Shell

10435

4203

52880

51630

11657

5396

BP

11158

10062

19208

16646

2979

1065

Chevron

6255

13327

5941

9955

11666

GRAPHIC: Slowing exploration -

https://graphics.reuters.com/OIL-EXPLORATION/azgpolnldvd/index.html

Of the five companies, BP saw by far the largest drop in new acreage acquisition in 2020. Bernard Looney, who became BP's CEO in February, outlined a strategy to reduce oil output by 40% or 1 million barrels per day by 2030. BP has rapidly scaled back its exploration team in recent months.

Exxon, the largest U.S. energy company, acquired the largest acreage in 2020 in the group, with 63% in three blocks in Angola, according to Rystad Energy.

Total was second with two large blocks acquired in Angola and Oman.

Acquiring exploration acreage means companies can search for oil and gas. If new resources are discovered in sufficient volumes, the companies need to decide whether to develop them, a costly process that can take years.

As a result, the drop in exploration activity could lead to a supply gap in the second half of the decade, analysts said.

(Graphic: Oil majors' spending - https://graphics.reuters.com/OILMAJORS-CAPEX/jznvnqwzdpl/index.html)

(Reporting by Ron Bousso; Editing by Alexander Smith)

Of the five companies, BP saw by far the largest drop in new acreage acquisition in 2020. Bernard Looney, who became BP's CEO in February, outlined a strategy to reduce oil output by 40% or 1 million barrels per day by 2030. BP has rapidly scaled back its exploration team in recent months.

Exxon, the largest U.S. energy company, acquired the largest acreage in 2020 in the group, with 63% in three blocks in Angola, according to Rystad Energy.

Total was second with two large blocks acquired in Angola and Oman.

Acquiring exploration acreage means companies can search for oil and gas. If new resources are discovered in sufficient volumes, the companies need to decide whether to develop them, a costly process that can take years.

As a result, the drop in exploration activity could lead to a supply gap in the second half of the decade, analysts said.

(Graphic: Oil majors' spending - https://graphics.reuters.com/OILMAJORS-CAPEX/jznvnqwzdpl/index.html)

(Reporting by Ron Bousso; Editing by Alexander Smith)