Abortion, race, gender: State Republicans wage culture wars

2021/8/2

©Stateline.orgPEW RESEARCH

In this photo from May 29, 2021, protesters hold up signs at a demonstration outside the Texas state capitol in Austin, Texas. - Sergio Flores/Getty Images North America/TNS

Not since the Supreme Court legalized abortion nationwide in 1973 has there been a year in which states approved so many abortion restrictions.

Since January, there have been a record 97 new laws limiting abortion enacted in 19 states, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a research and policy organization that supports abortion rights. While a handful of states also enacted laws designed to protect and expand access to abortion and other health care for pregnant women, the state restrictions far outnumbered them.

As a result, the gap between women’s access to abortion in some states as opposed to others has never been wider.

In addition to abortion, legislatures waded into other social issues during this year’s sessions. Republicans in many states pushed bills restricting transgender youth’s access to school sports and medical treatment for gender transition. They also sought to place limits on classroom discussions of systemic racism, vilifying a decades-old body of scholarship known as critical race theory.

Politics drove that rush of legislation, even as lawmakers faced pressing COVID-19 health and budget issues.

Republicans were emboldened in the 23 states where they control the governorship and both houses of the legislature. Other factors include a newly conservative U.S. Supreme Court, GOP backlash over former President Donald Trump’s reelection loss and a tidal wave of social media campaigns and commentary aimed at galvanizing conservatives by playing up divisive cultural issues.

James Henson, director of the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas at Austin, said the cultural issues play not only to Republican voters generally, but especially to the GOP conservative base, a much smaller subset who have outsized power in primaries. Lawmakers are aware that these voters hold the key to their elections, he said.

“If talking about cultural issues turns their key, [Republican lawmakers] are going to want to vote on those issues … and claim credit for fighting the fights on issues that are important to those voters,” he said in a phone interview. “Abortions, guns, sexualized issues.

“They are very big overarching issues, critical to these voters,” he said. “Not that they generate overall majority support in the electorate, or that they gin up so-called culture wars — it’s a function of the political,” he said, pointing out that while he is most familiar with Texas politics, the trends apply in other states as well.

There are currently 23 statehouses where Republicans hold the governorship and both houses in the legislature, a “trifecta,” according to Ballotpedia. These are where most of the conservative social issue legislation, including abortion, transgender and critical race theory laws, have been written this year.

There are 15 Democratic trifectas. A few of those states, including Colorado, Hawaii and New Mexico, have enacted laws designed to protect abortion rights if the Supreme Court overturns or significantly weakens Roe v. Wade.

Abortion laws

In June, the Supreme Court agreed to take a case on the constitutionality of a Mississippi law passed in 2018 that largely bars abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy. With a new 6-3 conservative majority on the high court, anti-abortion advocates see a chance to change federal law. Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch in a July court filing urged the justices to overturn Roe v. Wade.

Recent Montana measures typify the variety of abortion limits enacted nationwide.

Montana this year enacted a ban on abortions after 20 weeks past a woman’s last menstrual period; a requirement that pregnant women be offered the chance to see the fetus via ultrasound before they are allowed to have an abortion; a mandate for clinics to report extra data to the state, including history on prior pregnancies; prescribed procedures in the unlikely event of a failed abortion; and a ban on medical personnel using telemedicine to prescribe a medication abortion — the use of two drugs to terminate pregnancies up to the 10th week.

Elizabeth Nash, state issues expert at the Guttmacher Institute, said the 2020 elections shifted state legislatures more to the right, “and that opened the door for more abortion restrictions and bans. The other piece is that the Supreme Court is now solidly anti-abortion and that signaled to state legislators that the court would be more open to more restrictions on abortion.”

The COVID-19 health emergency led to a new twist on abortion restrictions — laws making it harder to prescribe medication abortions remotely. With the pandemic came a turn toward telemedicine instead of in-person visits that risked spread of the coronavirus. But some legislators, including those in Montana, sought to curb access to medication abortions by banning telehealth prescriptions and mailing of the drugs.

“Medication abortion can be provided safely and easily through teleheath,” Nash said. “There’s always some new twist on abortion restrictions. And this year the new twist is medication abortions.”

Montana lawmakers argued that prescribing abortion pills remotely could harm women if there were complications and they needed to seek emergency treatment. Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte signed the various bills, ending a string of vetoes in past years by former Democratic governors.

The biggest factor in the bills’ success?

“Gianforte won,” said Katie Glenn, counsel at the anti-abortion rights group Americans United for Life. “Montana had divided government for 16 years. In 2020, it got unified government.”

Montana state Rep. John Fuller, a Republican, said in a phone interview that he was pleased at the result.

“I made the argument on the floor regarding abortion,” he said, adding that he considers a fetus a “person” entitled to constitutional protections. “I have a belief that no unborn person can be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.”

Republicans in New Hampshire, too, secured a trifecta in 2020, leading to GOP Gov. Chris Sununu’s signing of a bill into law to prohibit abortions after 24 weeks beyond a woman’s last menstrual period.

New Hampshire also enacted a law mandating ultrasound of the uterus before a woman can have an abortion.

Transgender laws

Montana’s Fuller also took the lead in that state on a law requiring high school athletes to play on teams corresponding to the gender they were assigned at birth.

Fuller, a former high school teacher and wrestling, soccer and cross-country coach, argued that allowing transgender girls to compete on girls teams gives them an unfair advantage. But LGBTQ advocates say barring transgender kids from school sports would jeopardize their mental and physical health and increase their isolation.

Nationwide, eight bills prohibiting trans athletes from competing on teams with their chosen gender have been enacted, said Cathryn M. Oakley, state legislative director and senior counsel at the Human Rights Campaign, a group championing gay and lesbian rights. Those bills were in Arkansas, Montana, South Dakota, Oklahoma, Tennessee and North Dakota.

Oakley said one of the most sweeping laws was in Arkansas, which enacted a statute that prohibits trans youth from accessing surgery or hormonal treatment for gender transition. The bill was vetoed by Gov. Asa Hutchinson, a Republican, but the veto was overridden by the GOP-led legislature. A court injunction has prevented the law from taking effect, and the legal wrangling has just begun.

South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem, a Republican, at first vetoed a bill that would have banned transgender women and girls from female high school sports. But under pressure from the right, Noem, who may be considering a presidential run, backtracked and issued an executive order to impose the ban.

Oakley suggested that as gay, lesbian and transgender people become more accepted by Americans, and same-sex marriage is legal across the country, anti-gay lawmakers are looking for other sexual identity-based issues to confront.

“It’s harder to get people swept up in anti-LGBT rhetoric,” she said in a phone interview.

“Opinion is favoring not only LGBT folks but also trans folks as well.” Therefore, she said, the attention has turned to trans kids.

“The problem is the rhetoric: ‘Every trans girl who wants to play sports is taking an opportunity away from a cis girl who wants to play sports.’” Not true, she said.

But that is exactly Fuller’s argument. He pointed to a formerly male runner, now a trans female, who won the women’s mile race at the 2020 NCAA’s Division I Collegiate Conference Championship. “That took a championship away from a female,” he said. NCAA rules allow trans people to compete in competitions corresponding to their gender identity if they have been taking hormones to alter their gender for at least a year.

Critical race theory

Another flashpoint in the culture wars this year in state legislatures has been critical race theory, a vein of scholarship that studies racism at the systemic level, examining how policies, laws and court decisions can perpetuate racism even if they are ostensibly neutral or fair. Opponents argue that discussing race’s impact on society perpetuates racial divisions.

Eight states — Arizona, Idaho, Iowa, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas — this year enacted bans on teaching the topic in public schools despite no evidence that it is being taught in any public school.

Rashawn Ray, a David M. Rubenstein Fellow at the Brookings Institution think tank, who conducted a survey of the state actions, says the laws are designed as a “rebuke to changing American culture.”

According to Ray’s research, the laws mostly ban discussion, training or course orientation that portray the United States as inherently racist, as well as discussions about bias, privilege, discrimination and oppression. “Critical race theory wants us to take a social historical viewpoint on racism, and how it impacts our institutions,” he said.

Ray, who is also a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, said those concepts are generally too complex for most public school students and are more likely to be broached at the college level. Nonetheless, the debate is likely to have a chilling effect on teachers, he said.

He said teachers may be reluctant to try to explain the concept to students “because they could lose their jobs. Those are the problems.”

In New Hampshire, a conservative group called1776 Action launched a multimedia campaign calling for passage of an anti-critical race theory bill. Among its supporters, 1776 Action lists former HUD Secretary Ben Carson and former House Speaker Newt Gingrich. The bill was batted around in the legislature and eventually folded into the state’s budget.

After first saying he wouldn’t ban the teaching of critical race theory, Sununu signed the budget into law in late June, with the provision. His public statements put him on both sides of the issue. He said he didn’t necessarily believe in the tenets of critical race theory and was worried about raising free speech issues but would sign the bill anyway.

Shortly thereafter, more than half the members of his Council on Diversity and Inclusion quit.

“You signed into law a provision that aims to censor conversations essential to advancing equity and inclusion in our state, specifically for those within our public education systems, and all state employees,” the Council members wrote in their resignation letter. “Given your willingness to sign this damaging provision and make it law, we are no longer able to serve as your advisors.”

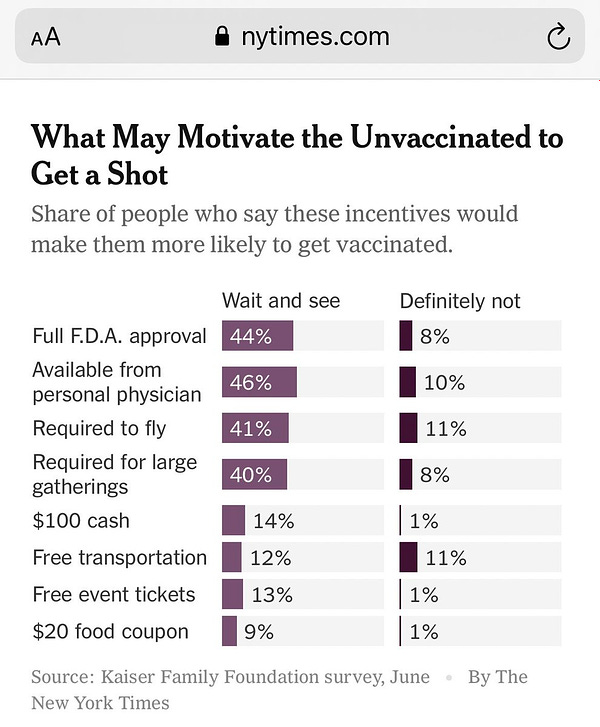

Ken Klippenstein @kenklippensteinPeople who say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if they got $100 cash: 14% People who say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if it was required to fly: 41%

Ken Klippenstein @kenklippensteinPeople who say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if they got $100 cash: 14% People who say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if it was required to fly: 41%

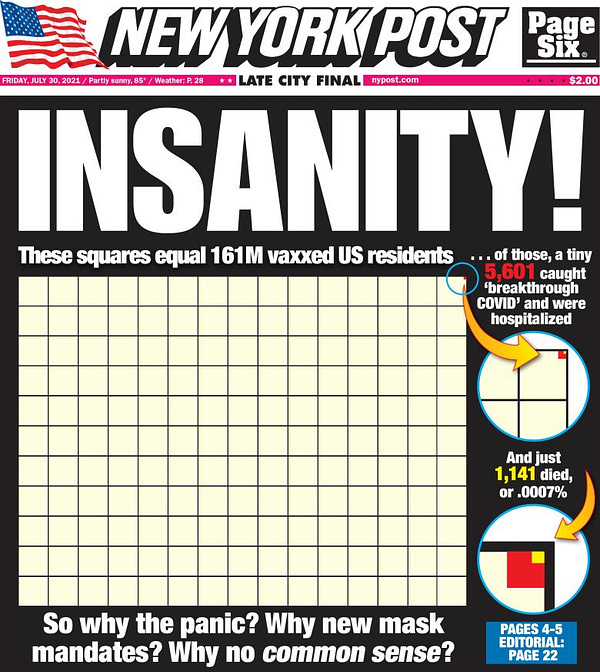

Tom Gara @tomgaraTowards a Murdochian pro-vaccine populism

Tom Gara @tomgaraTowards a Murdochian pro-vaccine populism