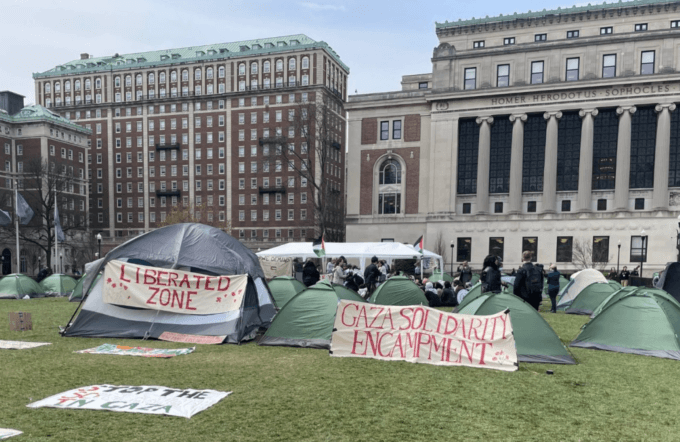

Columbia, NYU, The New School…MIT, Tufts, Emerson… Berkeley, Chicago, Chapel Hill… Everywhere…

I went to MIT, class of 1969, so I was a Senior in 1968. It is now 2024 not the late sixties, but rebellion for change is again in the air. I think it is just getting revved up. I can feel it. I’ll bet you can feel it too. And maybe, hopefully, it will not crescendo any time soon but will instead persist. And perhaps, hopefully, it will seek more than immediate changes. And maybe, and I think I can feel this too, it will be much smarter than we were back then, back in 1968.

The rebellious events at Columbia last week have spurred rebellions of students and sometimes others at a rapidly enlarging community of campuses, including at my personally much-despised alma mater, MIT. [Note, I am not unbiased about campus rebellion or about MIT. The former undergirds mass change, over and over. Have at it. The latter is an instance of elite, academic, grossly rotten business as usual. When I was president of MIT’s student body, during steadily growing and intensifying rebellion, among the epithets I used for MIT was “Dachau on the Charles” because of its war research. Some on campus were too literal or too dense to see why I named it thus. For them, I would acknowledge the main difference, which was that MIT’s victims were not local, like Dachau’s—no, MIT’s victims way back then were half a torn-up world away in Vietnam enduring American carpet bombing. And regarding Dachau, MIT’s victims were not hanging like burned out lightbulbs in MIT’s corridors nor lying breathless like fish out of water gassed in MIT’s labs. And now, 56 years later, MIT’s current victims are way off in Gaza enduring Israeli carpet bombing (but with American bombs). They are not being forcefully exiled from MIT’s classes, dorms, playing fields, and clinic—not yet, anyway. My point: history sometimes repeats, sometimes with ironic differences, sometimes with healthy differences.

One 1968 over-used, more hippie than political, and pretty stupid if catchy slogan was “don’t trust anyone over thirty” (except maybe Chomsky). I doubt that this time that slogan will reemerge much less change to “don’t trust anyone under seventy” so I hesitate to even write this reaction. Okay, hesitation finished. Being old may not bring wisdom but it doesn’t have to stifle solidarity. Decades have passed. Wrinkles have proliferated. But I actually remember MIT better than anywhere I ever lived before or since. So I can’t stop my elderly self from commenting.

Context 1: This past October, in response to decades of Israeli occupation, denigration, usurpation, and plentiful murder, Hamas orchestrated an escape from their open-air prison, and then raged and ravaged, including against civilians, and took hostages too.

The perpetrators’ anger was understandable, I think, and even warranted. Those colonized should not celebrate their colonizers. The perpetrators’ actions were also understandable, depending on your perspective and your capacity for objectivity. But the perpetrators’ actions were certainly not ethically justified or strategically wise. Hamas’s actions were instead stupidity and terroristic. But that was not because the jail breakers were militantly combative. Occupied peoples have a right to be—indeed ought to be—militantly combative. The colonized have a right to invade the colonizer. Not vice versa.

Context 2: Israel’s IDF has responded ever since. It claims its actions are justified by Hamas’ actions: Hamas struck first. Hamas killed innocent Israelis. We Israelis have to defend ourselves. We have to make them reap what they sowed. We have to assault the entirety of Gaza with some of the most intensive bombing per acre ever unleashed on anyone, anywhere—at least by other than the U.S. We must incinerate infrastructure. We must demolish homes, hospitals, schools, and basically anything that’s there to be hit. The U.S. in Vietnam said “anything that flies against everything that moves.” We Israelis learned from and adapted our benefactor’s ways. Thank you home of the brave. Thank you land of the free. But your Kissinger was too tame. We say, “anything that flies against everything.” Yes, you heard us right, everything. More, we intentionally, overtly, proclaim it out loud, as our stated policy, that we have to starve them all. We welcome the ensuing deaths. Deaths and destruction are our point. Die or leave is our message. And like our benefactor, we are good at what we do, which is why much of Gaza is already uninhabitable. It is why kids have their limbs amputated in bombed out hospitals—without anesthesia, their parents already permanently dead. It is why preventable, curable diseases spread with our blessing. Kill the vermin or at least to make them leave. And so we block medicine, food, and water to defend ourselves. Of course we do. We aren’t half-hearted about this. “Anything that destroys and kills against everything that exists wherever Hamas hides.” So what would happen if Hamas rented a safe house in Berlin or, more likely, New York? Even if he was a little too tame, Kissinger is our hero. If he couldn’t do it, we can.

Context 3: The U.S. government provides virtually endless supplies of bombs and any sought surveillance, and arguably just as important, the U.S. protects Israel from the UN and any other opposition. Those in Washington and on Wall Street literally cheerlead and celebrate Israel’s actions, even as some serious cracks spread.

Context 4: Many people who watch Israel’s horrifying actions unfold wring their hands, but stay silent. Some who watch root for the IDF, mostly that’s Israeli citizens, but also some in the U.S., Germany, and various other places. At worst some who root for the IDF say, “okay, bomb the hospitals and everyone in them. Get to it. Kids too. Extinguish the Vermin, babies and all. Nuke them if you have to.” Others sincerely bemoan the excess but keep quiet about it. No unseemly public pronouncements or displays for them. Then there are also others, a whole lot of others, increasingly many others, who will answer, if asked, “this is barbaric. This is terrorism. This should stop now.” And then, of those, some even express their disgust really loudly. Some chant it, some march and demonstrate it. Some pitch tents for it. And some may soon move inside from the campus courtyards to occupy offices and then buildings, too—all for Palestine. And, yes, it is true that some—but I bet very few—genocide protestors occasionally scream nasty, ill-chosen things not just wrong but also counter productive to their efforts. I suspect the few who do that, with their passion boiling over while they fear they may be risking their academic lives do it not least because Israeli and U.S. media and school administrators tell them that if you protest Zionism, if you protest genocide, you are anti-Semitic. What crap. So, they wonder, okay how are we supposed to demonstrate that we are not anti-Semitic but instead anti-anti-Semitic? “Say that, just that way” the authorities intone. “We do, but you refuse to hear us.” “Okay, then chant ‘we are Zionist. We support genocide,’” the authorities reply. “We’ll hear that.” Yes, that would work, administrators would hear that. But the students won’t say that. And neither should anyone else say that. And the students will be heard.

Back in 1965, in my Freshman year of college, I was a member of Alpha Epsilon Pi one of the campus’s Jewish fraternities, or I was up until when I demonstratively quit during the first week of my Sophomore year. But here’s the odd current thing. Somehow, lately, my name got onto a mailing list of AEPi alumni so I have, very recently, received a flurry of emails from ex-brothers sent to other ex-brothers. The precipitant for the flurry was an invitation to get together in Cambridge during the fifty-fifth anniversary of the class of 1969. After the first invitation, there came a round of discussion by various AEPi alumni, spurred by one brother who wrote he would love to come to break bread with his fraternity brothers, but in protest over what in his view was MIT President Kornbluth’s horrible hesitance to protect Jewish students from what this brother saw as grotesque anti-semitism, he would not come to the reunion. This is a very well educated and presumably humane and caring guy. His sentiment and his outrage at students supporting Palestine was then seconded and thirded, a few times over, with escalating whining about the plight of Jews at MIT but with barely a sincere, intelligent word about Palestinians at MIT or Palestinians anywhere else like, oh, say, in Gaza. Are there courses on head-in-the-sand hypocrisy at MIT? I found some of the contents of some of my ex- brothers’ inter-communications blindingly nauseating. And I take for granted you who are admirably and courageously protesting at MIT (and elsewhere) have already encountered similar and worse head-in-the-sand hypocritical castigation. Certainly those at Columbia have. Certainly you all will again, repeatedly.

Meanwhile, by way of offering something that may possibly prove useful, I think some of those who criticize you or who call for your expulsion (like some of my one-time fraternity brothers) will argue that decades of Israel’s terror did not justify Hamas’s few days of anti-civilian actions, yet somehow Hamas’s few days of anti-civilian actions do justify Israel’s now six month genocidal bombardment of everything and starvation of everyone in Gaza. They will tell you, utterly blind to their own illogic, that you are supporting terror. They may even say you are committing terror. Call them illogical, hypocritical, incredibly ignorant, or whatever you wish, but please say all that to yourself, in your own mind, if you must utter it at all. Please don’t rail that at them. Don’t curse them. Don’t ridicule them. That was our biggest mistake in 1968. My point is, please work to make them your allies, maybe not all of them, but most. Hit them with evidence. Hit them with logic. Hit them with reasoning. And hells bells, hit them with morality (but not holier than thou moralism). And also listen to them. Also address their words. Even sympathize with them. Don’t compromise, but sympathize. You have likely already seen all the dysfunctional, dismissive, and self-corrupting behavior they manifest and in all likelihood there is more to come. But please don’t mimic it. I am ashamed to say—but actually happy to report—that too often I and my movement allies did mimic their hostility. We did get tribal against our critics. Provoked, we did leave our reasoning behind. We did get holier than thou at them. And for all that we did accomplish, those choices were not only not helpful they were largely responsible for us not accomplishing much more than we did. The good news, the happy side, is that you can do better. Be militant for sure. Get to the heart of things, by all means. We did that much too. And fifty-six years later you have to deal with fascist fanaticism. For bequeathing you that, I/we apologize. So do better than us. Don’t repulse who should become and who can become allied with you. We repulsed too many, you don’t have to. Don’t only rebel, organize!

A lot of people are comparing now to 1968. That year was tumultuous. We were inspired. We were hot. But here comes this year and it is moving faster, no less. That year the left that I and so many others lived and breathed was mighty. We were courageous, but we also had too little understanding of how to win. Don’t emulate us. Transcend us.

That year’s election was Nixon versus Humphrey. Trump is way worse than Nixon. Biden is like Humphrey, and I even think somewhat better. That year’s Democratic Convention was in Chicago. So is this year’s. That year, in Chicago, the Sixties went wild in the streets. And Nixon won. And that event was part of why fifty-six years later you face fascist fundamentalism. This year, in Chicago, what? If there is a lesson from 1968 to apply, the movement must persist, but simultaneously Trump must lose. That means Biden—or someone else?—must win. And, of course, the emerging mass uprisings must persist and diversify and broaden in focus and reach. And hey, on your campuses, again do better than us. Fight to divest but also fight to structurally change them so their decision makers—which should be you—never again invest in genocide, war, and indeed suppression and oppression of any kind. Tomorrow is the first day of a long, long potentially incredibly liberating future. But one day is but one day. Persist.

This piece first appeared on ZNet.