Simple, fuel-efficient rocket engine could enable cheaper, lighter spacecraft

It takes a lot of fuel to launch something into space. Sending NASA's Space Shuttle into orbit required more than 3.5 million pounds of fuel, which is about 15 times heavier than a blue whale.

But a new type of engine—called a rotating detonation engine—promises to make rockets not only more fuel-efficient but also more lightweight and less complicated to construct. There's just one problem: Right now this engine is too unpredictable to be used in an actual rocket.

Researchers at the University of Washington have developed a mathematical model that describes how these engines work. With this information, engineers can, for the first time, develop tests to improve these engines and make them more stable. The team published these findings Jan. 10 in Physical Review E.

"The rotating detonation engine field is still in its infancy. We have tons of data about these engines, but we don't understand what is going on," said lead author James Koch, a UW doctoral student in aeronautics and astronautics. "I tried to recast our results by looking at pattern formations instead of asking an engineering question—such as how to get the highest performing engine—and then boom, it turned out that it works."

A conventional rocket engine works by burning propellant and then pushing it out of the back of the engine to create thrust.

"A rotating detonation engine takes a different approach to how it combusts propellant," Koch said. "It's made of concentric cylinders. Propellant flows in the gap between the cylinders, and, after ignition, the rapid heat release forms a shock wave, a strong pulse of gas with significantly higher pressure and temperature that is moving faster than the speed of sound.

"This combustion process is literally a detonation—an explosion—but behind this initial start-up phase, we see a number of stable combustion pulses form that continue to consume available propellant. This produces high pressure and temperature that drives exhaust out the back of the engine at high speeds, which can generate thrust."

Conventional engines use a lot of machinery to direct and control the combustion reaction so that it generates the work needed to propel the engine. But in a rotating detonation engine, the shock wave naturally does everything without needing additional help from engine parts.

"The combustion-driven shocks naturally compress the flow as they travel around the combustion chamber," Koch said. "The downside of that is that these detonations have a mind of their own. Once you detonate something, it just goes. It's so violent."

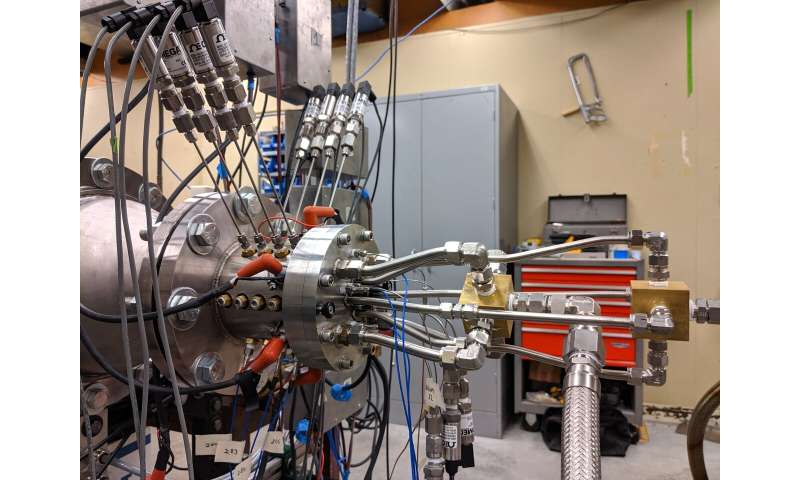

To try to be able to describe how these engines work, the researchers first developed an experimental rotating detonation engine where they could control different parameters, such as the size of the gap between the cylinders. Then they recorded the combustion processes with a high-speed camera. Each experiment took only 0.5 seconds to complete, but the researchers recorded these experiments at 240,000 frames per second so they could see what was happening in slow motion.

From there, the researchers developed a mathematical model to mimic what they saw in the videos.

"This is the only model in the literature currently capable of describing the diverse and complex dynamics of these rotating detonation engines that we observe in experiments," said co-author J. Nathan Kutz, a UW professor of applied mathematics.

The model allowed the researchers to determine for the first time whether an engine of this type would be stable or unstable. It also allowed them to assess how well a specific engine was performing.

"This new approach is different from conventional wisdom in the field, and its broad applications and new insights were a complete surprise to me," said co-author Carl Knowlen, a UW research associate professor in aeronautics and astronautics.

Right now the model is not quite ready for engineers to use.

"My goal here was solely to reproduce the behavior of the pulses we saw—to make sure that the model output is similar to our experimental results," Koch said. "I have identified the dominant physics and how they interplay. Now I can take what I've done here and make it quantitative. From there we can talk about how to make a better engine."

More information: James Koch et al, Mode-locked rotating detonation waves: Experiments and a model equation, Physical Review E (2020). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevE.101.013106