Lockdown measures have stopped many protesters from going outside. So they're getting creative.

Christopher Miller BuzzFeed News Contributor Posted on April 25, 2020

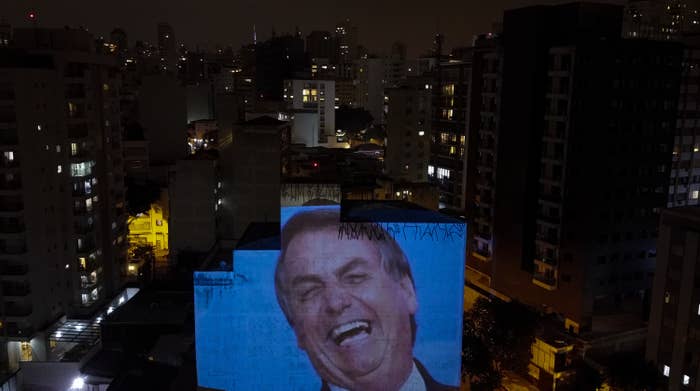

Miguel Schincariol / Getty Images

Images of the president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, projected onto a wall in protest at his handling of the pandemic.

How do you protest against the government if coronavirus lockdown measures mean you can’t go outside?

Simple.

Drop a pin.

By sticking thousands of pins embedded with protest messages onto online maps, Russians who are angry about lost jobs and lack of financial aid from the government were able to make themselves be heard by authorities and each other.

Using Yandex.Maps and Yandex.Navigator mobile apps — the Russian version of Google Maps — the virtual protesters dropped their first pins in front of government buildings in the southwestern Russian city of Rostov-on-Don on Monday. But it wasn’t long before more appeared outside government buildings and politically symbolic locations in Moscow and St. Petersburg, Yekaterinburg and Nizhny Novgorod, and even in the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk, according to local media reports. Their numbers quickly grew from hundreds to thousands protesting together across Russia.

Their beef? The impact of sweeping safety measures imposed in an attempt to stop the novel coronavirus outbreak in Russia, which as of Friday evening had recorded 68,622 cases and 615 deaths, according to government data. (The death toll remains low compared to other countries with a similar number of cases.) Because of those measures, which include orders to self-isolate at home — and, in the case of Moscow and Rostov on Don, the need to apply for special permits to leave home or else face a hefty fine and possible arrest — the demonstrators did not physically gather on the cities’ streets and squares, so they did it virtually.

Most of the participants demanded that Russian authorities introduce an official state of emergency, which would provide citizens with social assistance from the government, or else lift restrictions preventing people from going to work. Thousands of comments appeared on the apps over the course of the sprawling digital protests.

“No money to pay off loans! What are we supposed to do?” read one protest message posted in Rostov on Don that was seen by Global Voices, which covered the digital demonstrations and aggregated local media reports. “OK, so cancel taxes, loans, and so on,” and “declare a state of emergency or stop restrictions on people,” read others.

Дон-ТР@VestiDonTR

#ростов В Ростове устроили виртуальный митинг из-за введения новых пропусков https://t.co/HfKYtz2GFt01:19 PM - 20 Apr 2020

Reply Retweet Favorite

A virtual protest is being held in Rostov due to the introduction of new restrictions.

Watching as the protests spread, Alexander Plushchev, a popular blogger, asked followers on his Telegram channel, “I feel that by this evening, digital rallies will have taken over the whole country. Don’t those in the Kremlin get that?”

If 2019 was the year of the street protest, of tear gas and rubber bullets, 2020 might be the year the street protest died, or perhaps fell into a deep sleep, and went online.

“Before the coronavirus, there were quite dynamic public protests in so many different places, especially in the past six months, in Iran and in Hong Kong, in Moscow last summer … All over the world,” said Rachel Denber, deputy director of the Europe and Central Asia division at Human Rights Watch (HRW).

The deadly coronavirus pandemic has disrupted months-long protest movements across the world. Streets and squares in cities have gone eerily quiet.

Yet, as with the Russian protesters, some civil society activists and protest movement leaders are coming up with creative solutions to voice their discontent in this new era of social distancing and national lockdown orders.

Amnesty Hungary@AmnestyHungary

In #Poland the parliament will soon vote on two new laws - one to restrict #abortion, the other to ban #SexEducation We cannot take the streets, so we'll #ProtestAtHome @amnestyPL #NieSkladamyParasolek #StrajkKobiet @elzbietawitek @MorawieckiM @RyszardTerlecki08:37 AM - 15 Apr 2020

In neighboring Ukraine, for example, protesters held a Zoom conference call against the government’s decision to cut state funding to cultural programs. In Poland, protesters published photographs and posters on social media in support of women’s rights and against proposed laws to restrict abortion and ban sex education. Activists in Chile projected videos of demonstrations and of victims of state repression on public buildings.

There are some who push the physical boundaries of protesting in this moment of limits. In Brazil people expressed their anger at President Jair Bolsonaro’s controversial handling of the pandemic by banging pots and pans together while hanging out of their windows and stepping out onto their balconies. In Sao Paolo some protesters projected a picture of him laughing onto buildings to show their disgust. And in Hong Kong, a newly formed union born out of the pro-democracy movement that has been interrupted by the coronavirus went on strike to demand a ban on entries from mainland China to stop the spread of the virus.

Iavor Rangelov, an assistant professorial research fellow focused on human rights and security, transitional justice and civil society at the London School of Economics and Political Science, told BuzzFeed News that in many ways the current lockdown is accelerating trends that first appeared before the coronavirus

“The push by governments of different stripes to restrict the space for protest and social mobilization is one example,” he said. Another, he added, had forced activists to start doing more campaigning and organizing online.

Whether these protest methods can be effective and will sustain the larger movements remains to be seen and likely depends on how long governments keep measures restricting access to public spaces in place.

If the new, pandemic-inspired protest methods do turn out to be effective, Rangelov said it may lead governments to further restrict digital spaces. But this could have unforeseen consequences too.

“That carries more risks for activists but also for governments, when all ‘valves’ for protest get closed down the pressure builds up and may trigger much more disruptive and destabilizing forms of protests,” he said.

“Social movements that have been mobilizing around inequalities and injustices feel vindicated as the pandemic has exacerbated many of them and made them more visible. They are also frustrated that they can’t take full advantage of the opening to mobilize around these issues as much as they feel they should, especially offline.”

He added: “What will be important to watch is how broader society responds to some of their ideas and agendas that until recently were seen as marginal and utopian, but now seem possible.”

Amir Levy / Getty Images

Israelis protest under coronavirus restrictions on April 19, 2020.

Alexander Clarkson, a lecturer in European and international studies at King’s College London, said that we tend to overestimate the extent to which any single event leads to some radical change in protest movements.

“Lockdowns may in the long term ... change the way in which social movements think about things. Or, I actually think public health will become a dimension of protest movements established in preexisting causes in which it wasn’t,” he said. “I have more doubts about it being fundamentally transformative in the way social movements operate. As the lockdowns loosen, movements will come out into the streets increasingly and they’ll just go back to using these old tools they always did.”

Perhaps a sign of that came last weekend, when thousands of Israelis stood six feet apart in Tel Aviv’s Rabin Square to protest what they felt was the erosion of democracy under the current government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

In several US cities, people unhappy with state-ordered shutdowns have also flouted federal recommendations and opted for the more traditional method of protest: gathering in public. And they have done so with support from President Donald Trump, who urged supporters to “liberate” states that have imposed public safety measures.

Meanwhile, two dozen nurses from National Nurses United stood at a safe distance from each other in protest outside the White House on Tuesday. They demanded more personal protective equipment for themselves and others on the front line of the pandemic.

“The digital protest is just a means of expressing yourself at a moment in time because other means are not there,” Clarkson said.

If serious change in the context of protests is to emerge from the pandemic, Clarkson thinks it will come from the side of law enforcement. “People are talking about social movements changing, I think it will be policing that could change.”

“In an environment where, if the state is trying to do track-and-tracing, trying to maintain social distancing, trying to police and monitor a whole range of new potential infractions, and then on top of that deal with [protesters] … we may see states becoming even more brutal,” Clarkson said.

In a sign that Russia is unlikely to tolerate either, Yandex — which has come under increasing influence from the government — began digitally dispersing the online protesters by deleting their protest messages almost as quickly as they appeared.

Олег Степанов@olsnov

Прямо сейчас Яндекс разгоняет «несогласованный митинг» против Путина на Красной площади! Москвичи оставляют сотни комментариев, но администраторы их мгновенно удаляют. Попробуйте сами https://t.co/RCrZAqosdp01:26 PM - 20 Apr 2020

Right now Yandex is dispersing an “unsanctioned protest” against Putin on Red Square! Muscovites are posting hundreds of comments, but administrators are instantly deleting them. Try for yourself.

Christopher Miller is a Kyiv-based American journalist and editor.

Contact Christopher Miller at millerjchristopher@gmail.com.

Drop a pin.

By sticking thousands of pins embedded with protest messages onto online maps, Russians who are angry about lost jobs and lack of financial aid from the government were able to make themselves be heard by authorities and each other.

Using Yandex.Maps and Yandex.Navigator mobile apps — the Russian version of Google Maps — the virtual protesters dropped their first pins in front of government buildings in the southwestern Russian city of Rostov-on-Don on Monday. But it wasn’t long before more appeared outside government buildings and politically symbolic locations in Moscow and St. Petersburg, Yekaterinburg and Nizhny Novgorod, and even in the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk, according to local media reports. Their numbers quickly grew from hundreds to thousands protesting together across Russia.

Their beef? The impact of sweeping safety measures imposed in an attempt to stop the novel coronavirus outbreak in Russia, which as of Friday evening had recorded 68,622 cases and 615 deaths, according to government data. (The death toll remains low compared to other countries with a similar number of cases.) Because of those measures, which include orders to self-isolate at home — and, in the case of Moscow and Rostov on Don, the need to apply for special permits to leave home or else face a hefty fine and possible arrest — the demonstrators did not physically gather on the cities’ streets and squares, so they did it virtually.

Most of the participants demanded that Russian authorities introduce an official state of emergency, which would provide citizens with social assistance from the government, or else lift restrictions preventing people from going to work. Thousands of comments appeared on the apps over the course of the sprawling digital protests.

“No money to pay off loans! What are we supposed to do?” read one protest message posted in Rostov on Don that was seen by Global Voices, which covered the digital demonstrations and aggregated local media reports. “OK, so cancel taxes, loans, and so on,” and “declare a state of emergency or stop restrictions on people,” read others.

Дон-ТР@VestiDonTR

#ростов В Ростове устроили виртуальный митинг из-за введения новых пропусков https://t.co/HfKYtz2GFt01:19 PM - 20 Apr 2020

Reply Retweet Favorite

A virtual protest is being held in Rostov due to the introduction of new restrictions.

Watching as the protests spread, Alexander Plushchev, a popular blogger, asked followers on his Telegram channel, “I feel that by this evening, digital rallies will have taken over the whole country. Don’t those in the Kremlin get that?”

If 2019 was the year of the street protest, of tear gas and rubber bullets, 2020 might be the year the street protest died, or perhaps fell into a deep sleep, and went online.

“Before the coronavirus, there were quite dynamic public protests in so many different places, especially in the past six months, in Iran and in Hong Kong, in Moscow last summer … All over the world,” said Rachel Denber, deputy director of the Europe and Central Asia division at Human Rights Watch (HRW).

The deadly coronavirus pandemic has disrupted months-long protest movements across the world. Streets and squares in cities have gone eerily quiet.

Yet, as with the Russian protesters, some civil society activists and protest movement leaders are coming up with creative solutions to voice their discontent in this new era of social distancing and national lockdown orders.

Amnesty Hungary@AmnestyHungary

In #Poland the parliament will soon vote on two new laws - one to restrict #abortion, the other to ban #SexEducation We cannot take the streets, so we'll #ProtestAtHome @amnestyPL #NieSkladamyParasolek #StrajkKobiet @elzbietawitek @MorawieckiM @RyszardTerlecki08:37 AM - 15 Apr 2020

In neighboring Ukraine, for example, protesters held a Zoom conference call against the government’s decision to cut state funding to cultural programs. In Poland, protesters published photographs and posters on social media in support of women’s rights and against proposed laws to restrict abortion and ban sex education. Activists in Chile projected videos of demonstrations and of victims of state repression on public buildings.

There are some who push the physical boundaries of protesting in this moment of limits. In Brazil people expressed their anger at President Jair Bolsonaro’s controversial handling of the pandemic by banging pots and pans together while hanging out of their windows and stepping out onto their balconies. In Sao Paolo some protesters projected a picture of him laughing onto buildings to show their disgust. And in Hong Kong, a newly formed union born out of the pro-democracy movement that has been interrupted by the coronavirus went on strike to demand a ban on entries from mainland China to stop the spread of the virus.

Iavor Rangelov, an assistant professorial research fellow focused on human rights and security, transitional justice and civil society at the London School of Economics and Political Science, told BuzzFeed News that in many ways the current lockdown is accelerating trends that first appeared before the coronavirus

“The push by governments of different stripes to restrict the space for protest and social mobilization is one example,” he said. Another, he added, had forced activists to start doing more campaigning and organizing online.

Whether these protest methods can be effective and will sustain the larger movements remains to be seen and likely depends on how long governments keep measures restricting access to public spaces in place.

If the new, pandemic-inspired protest methods do turn out to be effective, Rangelov said it may lead governments to further restrict digital spaces. But this could have unforeseen consequences too.

“That carries more risks for activists but also for governments, when all ‘valves’ for protest get closed down the pressure builds up and may trigger much more disruptive and destabilizing forms of protests,” he said.

“Social movements that have been mobilizing around inequalities and injustices feel vindicated as the pandemic has exacerbated many of them and made them more visible. They are also frustrated that they can’t take full advantage of the opening to mobilize around these issues as much as they feel they should, especially offline.”

He added: “What will be important to watch is how broader society responds to some of their ideas and agendas that until recently were seen as marginal and utopian, but now seem possible.”

Amir Levy / Getty Images

Israelis protest under coronavirus restrictions on April 19, 2020.

Alexander Clarkson, a lecturer in European and international studies at King’s College London, said that we tend to overestimate the extent to which any single event leads to some radical change in protest movements.

“Lockdowns may in the long term ... change the way in which social movements think about things. Or, I actually think public health will become a dimension of protest movements established in preexisting causes in which it wasn’t,” he said. “I have more doubts about it being fundamentally transformative in the way social movements operate. As the lockdowns loosen, movements will come out into the streets increasingly and they’ll just go back to using these old tools they always did.”

Perhaps a sign of that came last weekend, when thousands of Israelis stood six feet apart in Tel Aviv’s Rabin Square to protest what they felt was the erosion of democracy under the current government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

In several US cities, people unhappy with state-ordered shutdowns have also flouted federal recommendations and opted for the more traditional method of protest: gathering in public. And they have done so with support from President Donald Trump, who urged supporters to “liberate” states that have imposed public safety measures.

Meanwhile, two dozen nurses from National Nurses United stood at a safe distance from each other in protest outside the White House on Tuesday. They demanded more personal protective equipment for themselves and others on the front line of the pandemic.

“The digital protest is just a means of expressing yourself at a moment in time because other means are not there,” Clarkson said.

If serious change in the context of protests is to emerge from the pandemic, Clarkson thinks it will come from the side of law enforcement. “People are talking about social movements changing, I think it will be policing that could change.”

“In an environment where, if the state is trying to do track-and-tracing, trying to maintain social distancing, trying to police and monitor a whole range of new potential infractions, and then on top of that deal with [protesters] … we may see states becoming even more brutal,” Clarkson said.

In a sign that Russia is unlikely to tolerate either, Yandex — which has come under increasing influence from the government — began digitally dispersing the online protesters by deleting their protest messages almost as quickly as they appeared.

Олег Степанов@olsnov

Прямо сейчас Яндекс разгоняет «несогласованный митинг» против Путина на Красной площади! Москвичи оставляют сотни комментариев, но администраторы их мгновенно удаляют. Попробуйте сами https://t.co/RCrZAqosdp01:26 PM - 20 Apr 2020

Right now Yandex is dispersing an “unsanctioned protest” against Putin on Red Square! Muscovites are posting hundreds of comments, but administrators are instantly deleting them. Try for yourself.

Christopher Miller is a Kyiv-based American journalist and editor.

Contact Christopher Miller at millerjchristopher@gmail.com.