The worldwide race to make solar power more efficient

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

One of the few parts of the UK economy to have a good April was solar power,

The Met Office says it has probably been the sunniest April on record and the solar power industry reported its highest ever production of electricity (9.68GW) in the UK at 12:30 on Monday 20 April.

With 16 solar panels on his roof Brian McCallion, from Northern Ireland, has been one of those benefitting from the good weather.

"We have had them for about five years, and we save about £1,000 per year," says Mr McCallion, who lives in Strabane, just by the border.

"If they were more efficient we could save more," he says, "and maybe invest in batteries to store it."

BRIAN MCCALLION

BRIAN MCCALLION

That efficiency might be coming. There is a worldwide race, from San Francisco to Shenzhen, to make a more efficient solar cell.

Today's average commercial solar panel converts 17-19% of the light energy hitting it to electricity. This is up from 12% just 10 years ago. But what if we could boost this to 30%?

More efficient solar cells mean we could get much more than today's 2.4% of global electricity supply from the sun.

Solar is already the world's fastest growing energy technology. Ten years ago, there were only 20 gigawatts of installed solar capacity globally - one gigawatt being roughly the output of a single large power station. For context, New York City, with 8.4 million people uses about 12 gigawatt-hours of electricity a day.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

By the end of last year, the world's installed solar power had jumped to about 600 gigawatts.

Even with the disruption caused by Covid-19, we will probably add 105 gigawatts of solar capacity worldwide this year, forecasts London-based research company, IHS Markit.

Most solar cells are made from wafer-thin slices of silicon crystals, 70% of which are made in China and Taiwan.

- The stealthy drones that fly like insects

- The secret chemical cocktails behind coronavirus testing

- Computer games: More than a lockdown distraction

- Coronavirus threatens the next generation of smartphones

- 'The phone slipped into the bath': Conference call tales

But wafer-based crystalline silicon is bumping pretty close to its theoretical maximum efficiency.

The Shockley-Queisser limit marks the maximum efficiency for a solar cell made from just one material, and for silicon this is about 32%.

However, combining six different materials into what is called a multi-junction cell can push efficiency as high as 47%.

Another way to break through this limit, is to use lenses to magnify the sunlight falling on the solar cell, an approach called concentrated solar.

But this is an expensive way to produce electricity, and is mainly useful on satellites.

"Not anything you would see on anybody's roof in the next decade," laughs Dr Nancy Haegel, director of materials science at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

The fastest improving solar technology is called perovskites - named after Count Lev Alekseevich von Perovski, a 19th Century Russian mineralogist.

These have a particular crystal structure that is good for solar absorption. Thin films, around 300 nanometres (much thinner than a human hair) can be made inexpensively from solutions - allowing them to be easily applied as a coating to buildings, cars or even clothing.

Perovskites also work better than silicon at lower lighting intensities, on cloudy days or for indoors.

You can print them using an inkjet printer, says Dr Konrad Wojciechowski, scientific director at Saule Technologies, based in Oxford and Warsaw. "Paint on a substrate, and you have a photovoltaic device," he says.

With such a cheap, flexible, and efficient material, you could apply it to street furniture to power free smartphone charging, public wifi, and air quality sensors, he explains.

He's been working with the Swedish construction firm Skanska to apply perovskite layers in building panels.

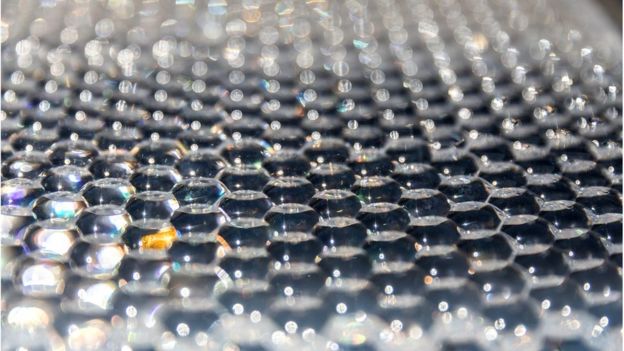

INSOLIGHT

INSOLIGHT

According to Max Hoerantner, co-founder of Swift Solar, a San Francisco start-up, there are only about 10 start-up firms in the world working on perovskite technology.

Oxford PV, a university spin-off, says it reached 28% efficiency with a commercial perovskite-based solar cell in late 2018, and will have an annual 250-megawatt production line running this year.

Both Oxford PV and Swift Solar make tandem solar cells - these are silicon panels which also have a thin perovskite film layer.

Since they're made from two materials, they get to break through the Shockley-Queisser limit.

The silicon absorbs the red band of the visible light spectrum, and the perovskite the blue bit, giving the tandem bigger efficiency than either material alone.

One challenge is when "you work with a material that's only been around since 2012, it's very hard to show it will last for 25 years," says Dr Hoerantner.

INSOLIGHT

INSOLIGHT

Insolight, a Swiss startup, has taken a different tack - embedding a grid of hexagonal lenses in a solar panel's protective glass, thus concentrating light 200 times.

To follow the sun's motion, the cell array shifts horizontally by a few millimetres throughout the day. It is a bid to make concentrated solar cheap.

"The architecture of these conventional concentrated photovoltaics is very costly. What we've done is miniaturise the sun tracking mechanism and integrate it within the module," says Insolight's chief business officer David Schuppisser.

"We've done it in a cheaper way [that] you can deploy anywhere you can deploy a conventional solar panel," he says.

The Universidad Politécnica de Madrid's solar energy institute measured Insolight's current model as having an efficiency of 29%. It is now working on a module that is hoped to reach 32% efficiency.

Current silicon technology is not quite dead, though, and there are approaches to make tiny, quick wins in efficiency. One is to add an extra layer to a cell's back to reflect unabsorbed light back through it a second time. This improves efficiency by 1-2%.

Another is to add an outside layer, which lessens losses that occur where silicon touches the metal contacts. It's only a "small tweak", says Xiaojing Sun, a solar analyst Wood Mackenzie research - adding 0.5-1% in efficiency - but she says these changes mean manufacturers only need to make small alterations to their production lines.

From such small gains - to the use of concentrated solar and perovskites - solar tech is in a race to raise efficiency and push down costs.

"Spanning this magical number 30%, this is where the solar cell industry could really make a very big difference," says Swift Solar's Max Hoerantner.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/ef/b0/efb0a152-6e68-4777-b148-a78747464260/babe-ruth-social-media-dimensions.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/f0/06/f0066459-8cd6-486a-ac4d-e3491bb593a3/gettyimages-96357907.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/6f/fc/6ffcea0f-ea5a-445b-b683-e584bdbd0227/gettyimages-549921185.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/ca/65/ca6548ad-cd01-4175-a609-60b51438e3c9/gettyimages-530858858.jpg)

:focal(1939x998:1940x999)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/0f/a5/0fa5489c-dc4e-495d-a55a-f9854f3ada53/ludington_wreckage_1.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/ac/8a/ac8a1886-28af-4a93-b854-5c7e3b2421b7/ludington_wreckage_3.jpg)

Cardboard coffins have been distributed amid a huge number of deaths

Cardboard coffins have been distributed amid a huge number of deaths

:focal(800x579:801x580)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/60/92/60928cf9-9287-47ec-9e53-e520b0d93e3a/herbert2.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/9b/38/9b389d15-186e-472d-8113-58cd29d2b500/herbert_spencer_5.jpg)