Climate breakdown means conditions that wrought devastation across Great Plains could return to region

AND ACROSS THE UKRAINE WHICH IS WRONGLY CALLED THE HOLODOMOR SINCE THE FAMINE WAS NOT MAN MADE BUT NATURAL RESULTING FROM THESE SAME CONDITIONS OCCURRING ACROSS THE PALLISER PLAIN ALSO WERE OCCURRING ACROSS THE SIBERIAN PLAIN.

Fiona Harvey Environment correspondent

Mon 18 May 2020

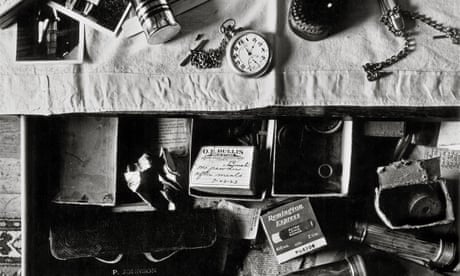

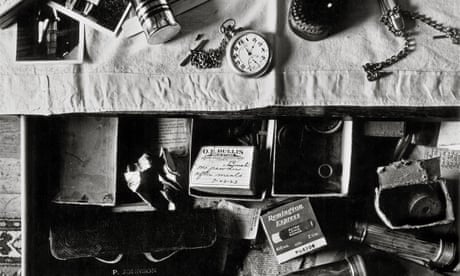

Abandoned farm buildings and machinery in the dust bowl caused by poor farming technique, as seen in May 1935. Photograph: Dorothea Lange/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

THE FAMOUS DOROTHEA LANGE

THE FAMOUS DOROTHEA LANGE

The agricultural conditions known as a “dust bowl”, which helped propel mass migration among drought-stricken farmers in the US during the great depression of the 1930s, are now more than twice as likely to reoccur in the region, because of climate breakdown, new research has found.

Dust bowl conditions in the 1930s wrought devastation across the US agricultural heartlands of the Great Plains, which run through the middle of the continental US stretching from Montana to Texas. The conditions are caused by a combination of heatwaves, drought and farming practices, replacing the native prairie vegetation.

Those conditions occurred in the 1930s, when they exacerbated the woes that farmers were already experiencing because of the wider economy, after two record-breaking heatwaves in 1934 and 1936, which are still the hottest US summers on record.

The dust bowl wanderer – in pictures

Such conditions could be expected to occur naturally only rarely – about once a century. But with rising concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, dust bowl conditions are likely to become much more frequent events.

They are now at least two and a half times more likely to occur, with a frequency probability of about once in 40 years, according to projections by an international group of scientists published on Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

If global temperatures rise by more than 2C (a rise of 3.6F) above pre-industrial levels, such heatwaves will become one-in-20-year events in the region, according to the study’s authors.

“Even highly industrialised parts of the world are vulnerable to extreme heat and drought,” said Friederike Otto, co-author of the study and acting director of the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford. “This is an important reminder that if we do not want events like the dust bowl, we need to get to net zero [greenhouse gas emissions] very soon,” she said.

Farming has changed in the region since the 1930s, with more widespread use of crop irrigation. But much of that relies on groundwater, which is also being severely depleted.

Huge fields, which encourage soil erosion; the tendency towards growing monocultures – vast areas given over to a single crop, such as maize or wheat; and a lack of natural vegetation all contribute to the creation of dust bowl conditions.

“If you don’t have trees anywhere, it’s much harder to keep water in the ground,” Otto said. “What crops you grow and how large the fields are have an effect on how the ground is able to hold water.”

Huge open fields with few borders have long been favoured by farmers as they are more efficient for mechanised tilling and harvesting. But in recent years some farmers have changed their practices to better conserve the soil, particularly after severe droughts in 2017.

Tim Cowan, lead author and research fellow at the University of Southern Queensland, said the study concentrated on the impacts of temperature rises but that land management would have a big impact too. However, improving land management could not remedy the damage done by the climate emergency. “Even though you have better practices in cropping now, the rises in temperature reduce those benefits, so there would still be a negative impact,” he said.

The researchers also found that there was a small but detectable impact from greenhouse gases on the dust bowl conditions of the 1930s.

Gabi Hegerl, co-author, and professor of climate system science at the University of Edinburgh, said: “With summer heat extremes expected to intensify over the US throughout this century, it is likely that the 1930s records will be broken in the near future.”

The climate model used by the researchers, developed at Oxford, runs on the personal computers of volunteers from around the world.

Dust bowl conditions in the 1930s wrought devastation across the US agricultural heartlands of the Great Plains, which run through the middle of the continental US stretching from Montana to Texas. The conditions are caused by a combination of heatwaves, drought and farming practices, replacing the native prairie vegetation.

Those conditions occurred in the 1930s, when they exacerbated the woes that farmers were already experiencing because of the wider economy, after two record-breaking heatwaves in 1934 and 1936, which are still the hottest US summers on record.

The dust bowl wanderer – in pictures

Such conditions could be expected to occur naturally only rarely – about once a century. But with rising concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, dust bowl conditions are likely to become much more frequent events.

They are now at least two and a half times more likely to occur, with a frequency probability of about once in 40 years, according to projections by an international group of scientists published on Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

If global temperatures rise by more than 2C (a rise of 3.6F) above pre-industrial levels, such heatwaves will become one-in-20-year events in the region, according to the study’s authors.

“Even highly industrialised parts of the world are vulnerable to extreme heat and drought,” said Friederike Otto, co-author of the study and acting director of the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford. “This is an important reminder that if we do not want events like the dust bowl, we need to get to net zero [greenhouse gas emissions] very soon,” she said.

Farming has changed in the region since the 1930s, with more widespread use of crop irrigation. But much of that relies on groundwater, which is also being severely depleted.

Huge fields, which encourage soil erosion; the tendency towards growing monocultures – vast areas given over to a single crop, such as maize or wheat; and a lack of natural vegetation all contribute to the creation of dust bowl conditions.

“If you don’t have trees anywhere, it’s much harder to keep water in the ground,” Otto said. “What crops you grow and how large the fields are have an effect on how the ground is able to hold water.”

Huge open fields with few borders have long been favoured by farmers as they are more efficient for mechanised tilling and harvesting. But in recent years some farmers have changed their practices to better conserve the soil, particularly after severe droughts in 2017.

Tim Cowan, lead author and research fellow at the University of Southern Queensland, said the study concentrated on the impacts of temperature rises but that land management would have a big impact too. However, improving land management could not remedy the damage done by the climate emergency. “Even though you have better practices in cropping now, the rises in temperature reduce those benefits, so there would still be a negative impact,” he said.

The researchers also found that there was a small but detectable impact from greenhouse gases on the dust bowl conditions of the 1930s.

Gabi Hegerl, co-author, and professor of climate system science at the University of Edinburgh, said: “With summer heat extremes expected to intensify over the US throughout this century, it is likely that the 1930s records will be broken in the near future.”

The climate model used by the researchers, developed at Oxford, runs on the personal computers of volunteers from around the world.