JUST LIKE THE IWW WAS A HUNDRED YEARS AGO,

POLICE BRUTALITY

HAS BEEN AROUND A LONG TIME

The Justice Department Campaign Against the IWW, 1917-1920

by Steven Parfitt

IWW picnic to raise funds for "class war prisoners," Seattle, July 20, 1919. UW Libraries, Labor Archives and Special Collections. (click to enlarge)

IWW picnic to raise funds for "class war prisoners," Seattle, July 20, 1919. UW Libraries, Labor Archives and Special Collections. (click to enlarge)

The Palmer Raids are usually remembered as the high water mark of the First Red Scare. Under the leadership of A. Mitchell Palmer, Woodrow Wilson’s Attorney General from 1919 to 1921, the Bureau of Investigation launched raids in November 1919 and January 1920 against anarchists, members of the new Communist and Communist Labor Parties, and others seen as supporters of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. Hundreds of foreign nationals were deported to Soviet Russia with the help of immigration officials from the Department of Labor. The Palmer Raids have been immortalised in literature and cinema. They launched the career of J. Edgar Hoover, then only twenty-four but a rising star within the Bureau of Investigation. They also launched the Bureau as the federal government’s first line of defence against Bolshevism in particular and left-wing radicalism in general.

All the attention given to the Palmer raids, however, has obscured the first great use of the Bureau of Investigation several years earlier against a domestic enemy: the Industrial Workers of the World. On September 5, 1917, agents of the Bureau of Investigation, in conjunction with local law enforcement, raided every office of the IWW across the United States within the space of twenty four hours, with possibly the widest-ranging search warrant in US history. They took five tons of material from the national headquarters of the IWW in Chicago alone, and took tons more from 48 local offices and the homes of leading Wobblies (IWW members). Federal agents seized everything from office furniture to paper clips. The District Attorney for Detroit complained to Thomas Gregory, Attorney General from 1914 to 1919, that it ‘became necessary to procure wagons to haul the stuff’ removed from the home of only one Wobbly, Herman Richter.[1]

Steven Parfitt is a Teaching Associate at the Universities of Nottingham and Loughborough and Associate Lecturer at University of Derby in the UK. He is author of Knights Across the Atlantic: The Knights of Labor in Britain and Ireland, forthcoming in 2016 with Liverpool University Press. He has written articles on American, British and global labour and social history (including the IWW) in journals including Labor, International Review of Social History and Labour History Review, and is currently working on a global history of the Knights of Labor. He can be reached at spar232@aucklanduni.ac.nz .

Some government officials claimed that the seized material ‘was sought by the government as evidence tending to connect I.W.W. leaders with the German war office.’ The District Attorney for Philadelphia hinted at other motivations when he described the September raids as done ‘very largely to put the I.W.W. out of business.’[2] Justice Department officials then used the captured documentation to prosecute more than a hundred IWW leaders at Chicago. The Chicago trial became one of the largest show trials held outside Stalin’s Russia. The defendants were all found guilty, after less than an hour’s deliberation by the jury, of more than 10,000 individual violations of federal law. Fifteen of them received twenty-year prison sentences, and though some of these sentences were later commuted the raids, trials, and other repression hamstrung the IWW at one of the most promising times in its history. This essay concerns the September raids, the trial that followed, and the elaborate mix of censorship, propaganda and other methods that federal agents used to secure the conviction of the Chicago defendants. It is, in other words, the story of an unprecedented attack by the federal government against a political movement on more or less explicitly political grounds.

Raids, Censorship and Surveillance

The reasons behind the federal government’s campaign against the IWW stretched back almost to the foundation of the IWW in 1905, but the immediate cause of that campaign lay in the wider war in Europe. When the United States entered the First World War in April, 1917, the IWW became one of the leading voices against the conflict. IWW organisers roamed the United States and established powerful branches in two crucial wartime industries in particular – copper mining and lumber. They did so in the context of an industrial boom, stimulated by the demand for war material from the United States and Allied governments. That boom brought unemployment down from 15% in 1914 to 8% in 1917 and, at the same time, encouraged a wave of unrest across the entire country that broke all records for industrial conflict.[3] Three thousand strikes took place between April and November 1917.[4] Business and government leaders worried that these battles might hamper if not completely disrupt the war effort, and the Wilson Administration moved to grant concessions to unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor in return for industrial peace. The IWW, the most radical, anti-war and uncompromising section of the American labor movement, was marked out for repression instead.

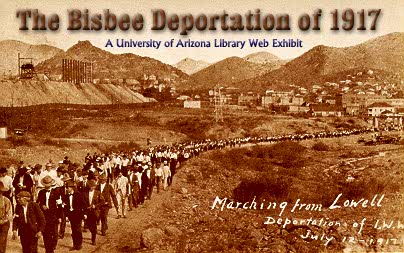

That repression came from several quarters. Employers, particularly the Phelps Dodge Corporation, which owned a string of copper mines in Arizona, were not about to let the Wobblies lead their employees on strike. In July 1917, after IWW locals called strikes at Phelps Dodge mines in Bisbee and Jerome, Arizona, the company and biddable sheriffs struck back. On July 10, mine supervisors and vigilantes rounded up more than a hundred men in Jerome and deported 67 of them to Needles, California. On July 12, the local sheriff and a posse of more than 2,200 men rounded up more than a thousand suspected IWWs at Bisbee and left them in the desert 200 miles beyond the city limits, in cattle cars helpfully provided by the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad. A kind of corporate-vigilante axis got to work on the Wobblies in other parts of the country as well. In August 1917, masked men broke into the hotel room of an IWW organiser, Frank Little, in Butte, Montana. They hanged him from a railroad trestle and left a warning to other labor agitators on his body. Little had arrived in the town to support miners on strike against the Anaconda Mining Company, and the company was almost certainly implicated in his murder.

The military joined the anti-IWW crusade in earnest. The War Department claimed that during hostilities its soldiers put down twenty-nine revolts, most of which actually referred to strikes called by the IWW. Lawmakers gave army units the power to use force in defence of anything that state governors declared a “public utility.” In practice this meant that, as Robert Goldstein writes, military personnel ‘began a massive program of strike-breaking, including raids on IWW headquarters, breaking up meetings, arresting and detaining hundreds of strikers under military authority without any declaration of war, and instituting a general reign of terror against the IWW.’[5] Military Intelligence, which grew from 2 to 1300 employees from the beginning to the end of the war, contained a domestic counter-intelligence service, MI-4, which spent a large fraction of its resources in spying on and disrupting IWW branches across the United States. This included the Plant Protection Service, made up of informants at all the major munition plants in the country that kept tabs on the political activities of their co-workers and paid particularly close attention to the doings of the IWW.[6]

The Justice Department went farthest of all in their repression of the Wobblies. The Bureau of Investigation, founded in 1908, had only 141 employees in 1914. As war loomed the Bureau rapidly increased its force of special agents, quintupling them between 1916 and mid-1918. They could also draw on the services of 150,000 volunteer patriots grouped into the American Protective League, which acted as an auxiliary to the Bureau’s more reliable and effective force of special agents. Attorney General Gregory did not boast idly when he claimed, in the Justice Department’s annual report for 1918, that ‘it is safe to say that never in its history has this country been so thoroughly policed as at the present time.’[7] Once Congress voted to declare war on Germany in April 1917 the Justice Department turned to the IWW as Enemy No.1. Congress also provided the main legislative weapon that the Department used against the IWW: the Espionage Act.

It is easy to see why the Espionage Act has re-emerged as the weapon of choice for Attorney Generals in the Bush and Obama Administrations against whistle-blowers like Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning. Passed in June 1917, the Act contained provisions that prosecutors could use in almost any conceivable contingency. It demanded harsh sentences for causing or attempting to cause ‘insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, refusal of duty, in the military or naval forces of the United States,’ and allowed for conspiracy charges for this crime. The Act further allowed the Post Office Department to restrict from the mails any material ‘advocating or urging treason, insurrection or resistance to any law of the U.S.’[8] William Fitts, a senior attorney working for the Justice Department, quickly noted the relevance of the Act to the Department’s campaign against the Wobblies. Along with several presidential proclamations and congressional resolutions the Act contained, as he later wrote to a colleague in July 1918, ‘the only statutes known to this Department which bear upon the activities of the I.W.W.’[9]

The Department soon acted on this enormous expansion of their legal powers. A memorandum from Assistant Attorney General Charles Warren to all Justice Department attorneys and agents on July 16 urged the use of every possible means to build up a complete picture of the IWW organisation, its plans and its leadership.[10] In September, the Los Angeles Times claimed that ‘for many weeks past, the activities of Industrial Workers of the World leaders have been under close scrutiny of the department’s bureau of investigation. Scores of field workers, chiefly in the West and Middle West, have devoted their undivided attention to alleged attempts on the part of leaders to embarrass the government in the conduct of the war by strikes and other disturbances called in the name of labor.’[11]

That report appeared just after the Bureau of Investigation conducted the September raids. They did so, as we saw at the start of this essay, partly to paralyse the IWW and partly to build up a more detailed picture of their activities. The raids certainly deprived the Wobblies of all the bureaucratic tools needed to run a national movement, from the pens, pencils and typewriters needed to write out reports and correspondence to the desks used to write them on, and the filing cabinets intended to catalogue and store them. The raids also netted the Justice Department an enormous volume of internal correspondence, mailing lists and other valuable information.

Attorneys scoured through the captured material and quickly drew up an indictment of 166 leading Wobblies that charged them with violating provisions of the Espionage Act, various presidential proclamations, and a number of other congressional resolutions and federal statutes. Taken together, the New York Times claimed, the Justice Department charged the defendants with ‘‘the crime nearest to treason within the definition of the criminal code.’[12] They proved these charges with a series of “overt acts,” which consisted, as Philip S. Foner has described it, ‘entirely of official statements, policy declarations, newspaper articles, and personal expressions of opinion in private and organization correspondence.’[13] This novel definition of an overt act certainly rested on shaky constitutional grounds. Perhaps realising this, the Justice Department put together an impressive collection of attorneys to bring the prosecution to a successful finish. The Chicago Daily Tribune declared that ‘the array of legal talent now in Chicago working on these cases is perhaps the greatest which the government has called together since the famous “Beef Trust” case.’[14]

While the lawyers put together their case the Bureau of Investigation directed Special Agent George N. Murdock to arrange and classify the great mass of material captured in September. Murdock’s work must rank as one of the great bureaucratic triumphs of the FBI’s history. He drew up lists, arranged in alphabetical order, of all the newspapers, stickers and pamphlets captured during the raids. He compiled a dossier on each individual defendant, using seized correspondence, and listed and annotated the wide range of minute books, mailing lists, convention proceedings, account books and financial statements taken by federal agents. Murdock even made an “Incomplete Inventory Office Furniture,” giving historians an unrivalled view upon the table, chair and desk situation that Wobblies faced in the summer of 1917.[15] On a more serious note, Murdock’s labors allowed the Justice Department to build up a very sophisticated picture of the IWW’s finances, the number and names of its members, and its organising activities and plans. This knowledge allowed the Department to refine its indictment of the 166 defendants at Chicago and prepare new legal assaults against other Wobblies.

The federal campaign against the IWW did not stop there. The Espionage Act, along with the power to raid and indict subversives of various kinds, also gave the government the power to deny the use of the US Postal Service to publications and correspondence deemed harmful to the war effort. Justice Department officials began by harassing the IWW defence campaign and threatening foreign-born Wobblies with immigration proceedings.[16] With the date of the Chicago trial set for April 1918, the prosecution decided to prevent the IWW from using the postal service to send out their newspapers, circulate defence literature, or even solicit contributions through the post for their defence fund.

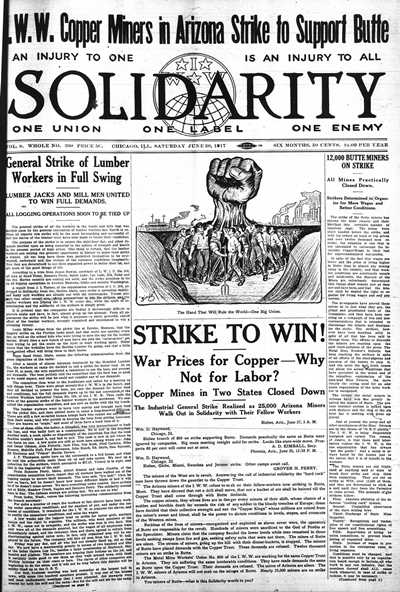

In this June 30, 1917 issue, Solidarity avoided outright opposition to the war mobilization while promoting lumber and copper strikes that the government claimed hurt the war effort. Click to see maps and details about IWW newspapers.

In this June 30, 1917 issue, Solidarity avoided outright opposition to the war mobilization while promoting lumber and copper strikes that the government claimed hurt the war effort. Click to see maps and details about IWW newspapers.

Prosecutors had a reliable friend in Postmaster-General Albert Burleson, a Texan who was no friend of organised labor. Burleson ordered the Solicitor General of the Post Office, W.H. Lamar, to decide whether IWW material was fit to pass through the mails.[17] That order had predictable results. Lamar banned the IWW’s two main publications, Solidarity and Industrial Worker, as well as all IWW defence bulletins and most of the organisation’s other correspondence. In one notable instance he declared that an IWW resolution against sabotage could not pass through the Postal Service on the grounds that it used the word sabotage. Burleson reported to Congress in 1919 that all of the items that the IWW deposited for circulation at the Chicago Post Office ‘was of a questionable character and approximately 99 per cent was of a character prohibited by law.’[18] Indeed, Lamar lamented to the prosecutors that the sheer volume of IWW literature impounded by Post Office inspectors caused ‘congestion’ in the Chicago Post Office![19]

The IWW was not the only victim of Lamar, Burleson and the Justice Department. The Socialist Party was denied the use of the mails for its own publications and circulars. Lamar impounded certain issues of liberal journals like the Nation and threatened the New Republic with similar consequences. He banned a National Civil Liberties Bureau (predecessor of the ACLU) pamphlet that challenged one of his earlier decisions. He banned an Irish-American magazine that quoted Thomas Jefferson in support of Irish independence, on the grounds that it would embarrass America’s wartime ally, Britain. The director of a movie was even arrested under the Espionage Act for depicting a massacre of civilians by British redcoats during the American Revolutionary War. The title of the film, subsequently banned, was The Spirit of ’76.[20]

But the IWW always remained at the front of the censors’ minds. When Carlton Parker, Dean of the Business School at the University of Washington, wrote an article mildly sympathetic to their plight in the December 1917 issue of the Atlantic Monthly, the Justice Department sprang into action. Frank Nebeker, a leading member of the team prosecuting the Wobblies at Chicago and a former attorney for copper mine companies like Anaconda and Phelps Dodge, raged to the Attorney General that Parker’s article had failed to highlight the ‘anti-patriotic, anti-war and essentially criminal’ character of the IWW.[21]Claude Porter, another member of the prosecution team, urged serious action against ‘a propaganda... being organized that has for its object creating public sentiment favourable to the I.W.W. with a view of influencing the verdict of the jury in the Haywood case.’ Nebeker further demanded that anti-IWW censorship be extended to all federal employees. They should not, he told the Attorney General, be allowed to say anything in public that might be construed as sympathetic to the Wobblies.[22]

The IWW received a brief respite from this all-pervasive censorship just before the Chicago trial was due to start. In late March 1918, their defence attorneys attempted to use federal censorship as part of a general attack on the constitutionality of the methods used by the Justice Department to obtain the evidence displayed in their indictment. Attorney General Gregory reassured the prosecution that this was temporary. ‘Move for search warrants demanded by Post Office Department soon as you can safely do so,’ he wrote to them on March 18, ‘without complicating issue respecting the papers in Haywood case.’[23] After that temporary blip the programme of surveillance and censorship went on unabated.

Trials and Lost Opportunities

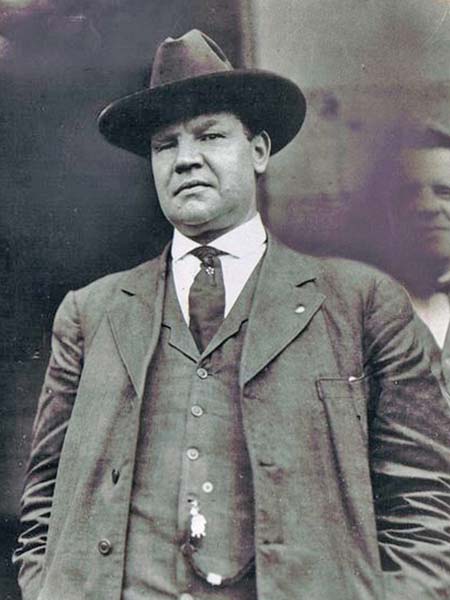

William "Big Bill" Haywood was the lead defendant in the Chicago trial that opened April 1, 1918.

William "Big Bill" Haywood was the lead defendant in the Chicago trial that opened April 1, 1918.

The trial of IWW leaders at Chicago finally began, appropriately enough, on April Fools’ Day, 1918. Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis presided. The 166 defendants, led by their leader, William “Big Bill” Haywood, had been reduced to 113 between September and April, and this number was further reduced when one of the defendants charged with convincing Americans to resist the draft, A.C. Christie, turned up to court in military uniform and on leave from his army unit. Eleven others were also dismissed, leaving 101 defendants in all. The trial almost collapsed at the outset when the court came to choose a jury. Obvious irregularities in that process aided the prosecution. There are suggestions that Attorney General Gregory had privately urged Landis to start the selection procedure all over again after the prosecution quickly used up their challenges on prospective jurors. The selection process was indeed halted, and the existing pool of jurors dismissed, after it was discovered that members of the defence team had approached one of their relatives. The new pool proved more amenable to the prosecution than the first might have been.[24]

The trial lasted for more than four months, from April 1 through to the middle of August. The prosecution made no attempt to prove the charges listed in the indictment. Prosecutors instead read out inflammatory passages from IWW newspapers, circulars and pamphlets to the court. They ‘indicted the organization,’ Melvyn Dubofsky writes, ‘on the basis of its philosophy and its publications.’[25] Guilt by the written word replaced guilt by deed. The defence team did its best under the circumstances. George Vanderveer, the IWW’s principal attorney, brought Wobblies to the witness stand by the score. J.T. “Red” Doran, one of the IWW’s most popular agitators, lightened the mood in the courtroom when he gave testimony in June and illustrated his lecture on political economy with chalk and blackboard. ‘Usually we have questions and literature for sale and collections,’ he finished, to laughter from the court, ‘but I think I can dispense with that today.’[26]

Vanderveer refused to give a closing statement, possibly on the grounds that as the prosecution had not attempted to prove their case there was no point rebutting arguments that had not been made. It probably made no difference to the outcome of the trial. In mid-August, Judge Landis, who had studiously maintained an air of impartiality throughout the proceedings, instructed the jury on how to go about determining guilt or innocence in a case involving more than 10,000 violations of federal law. The jury retired to consider their verdict on August 17.

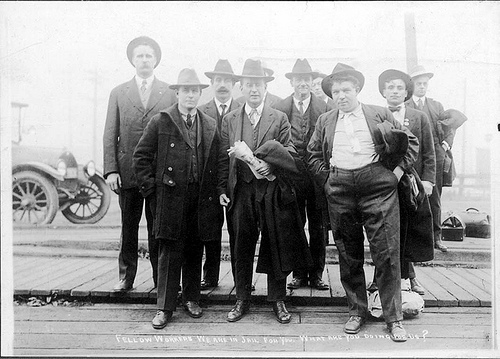

"Fellow workers we are in Jail for you. What are you doing for us?" reads the inscription on this photo of IWW members on their way to prison, probably 1919. UW Libraries, Labor Archives and Special Collections

"Fellow workers we are in Jail for you. What are you doing for us?" reads the inscription on this photo of IWW members on their way to prison, probably 1919. UW Libraries, Labor Archives and Special Collections

They did not make the defendants wait very long. Less than an hour later they returned and found all 101 Wobblies guilty on every charge that the prosecution had thrown at them. The defence was naturally shocked; but on reflection they probably should not have been. The government and press had carefully nurtured a public image of the IWW as anarchist bomb-throwers, pro-German saboteurs and slavish supporters of the Bolshevik Revolution, and the prosecution team had successfully reinforced that image in the minds of the jurors even if they didn’t choose to substantiate the contents of their indictment. The defendants were the kind of people who might do such dastardly things, even if nobody had proved that they had done them; this was probably the line of reasoning that led twelve jurors to find the Wobblies guilty on all counts. On August 31, Judge Landis handed the accused their sentences. Fifteen received the legal maximum of twenty years in jail, thirty-three received ten years, thirty-one received five, eighteen received lesser sentences, and together they incurred more than $2 million in fines. It later transpired than one of them, 19-year-old Ray Fanning, was not even an IWW member. Guilty or not, the defendants were quickly bundled off to the federal prison at Leavenworth, Kansas.[27]

Other trials followed the one at Chicago. More than forty IWWs went on trial at Wichita, Kansas, in December 1919 after two years in prison conditions so poor that some of the defendants died before appearing in court. All surviving defendants were found guilty and were sentenced to between three and nine years.[28] Around twenty Wobblies initially faced similar charges at Sacramento, California, before thirty more joined them after unknown arsonists bombed the Governor’s Mansion. The police then added members of the IWW defence campaign to the indictment. Theodora Pollak, for instance, arrived to pay the bail of some of the IWW defendants. She was promptly robbed of the money by police, arrested, forced to undergo a medical exam usually performed on prostitutes, and locked up with the people she had come to set free. Again, all of the defendants were found guilty and given prison time.[29] IWW members who attended the 1917 convention of the Agricultural Workers’ Industrial Union in Omaha, Nebraska were slightly luckier than the others. They were all arrested on 17 November, 1917, and were released in April 1919 without ever appearing in court.[30]

Wobblies outside prison suffered defeats as well. The mining companies, vigilantes and local, state and federal police conspired to keep them from returning to the copper mine towns of Arizona and Montana. Federal army units entered the lumber camps of the Northwest to remove the IWW’s influence there, and by the end of the war the production of lumber was carried out partly by uniformed soldiers operating under military discipline.[31] The Wilson Administration spared no expense, and left no means untried, in their campaign to root out the Wobblies wherever they happened to raise their heads and organise. Ongoing surveillance, the knowledge gleaned from the material captured in September 1917, and the removal of the entire national leadership to prison made this task much easier. The vast majority of victories that IWWs won against the federal government at this time were moral rather than actual ones. After a year of protests, for instance, an IWW local in Salt Lake City forced the Justice Department to return a typewriter, a waste paper basket and two lead pencils that federal agents had carried away in the September raids.[32]

IWW prisoners just before surrendering at federal penitentiary, Leavenworth, Kansas. UW Libraries, Labor Archives and Special Collections

IWW prisoners just before surrendering at federal penitentiary, Leavenworth, Kansas. UW Libraries, Labor Archives and Special Collections

The “guilty” Wobblies remained in prison during the great strikes of 1919, the Palmer Raids and all the repression of the First Red Scare. They remained there even when the new Republican Administration of Warren G. Harding decided to release Eugene Debs, the four-time presidential candidate for the Socialist Party who had been tried under the Espionage Act for making an anti-war speech in 1918, from jail in 1921. Their cause suffered further when Big Bill Haywood and eight of their other leaders skipped bail and escaped to Soviet Russia in 1921, even as the question of whether the IWW should support or oppose the Bolshevik government divided Wobblies in and out of prison.

Justice Department attorneys exacerbated these splits with an offer to commute the sentences of all IWWs on the condition that they promised to ‘be law-abiding and loyal to the Government of the United States and will not advocate or encourage disloyalty or lawlessness in any form.’[33] Some of the defendants, mentally and physically exhausted by their treatment by the federal government, gave in and made that promise, which essentially prevented them from engaging in IWW activities in the future. The rest refused to surrender in this way and remained behind bars. Eventually, in the mid to late 1920s, the last holdouts were released from jail and the federal government’s wartime suppression of the IWW concluded, more than half a decade after the end of the war.

The raids, trials, censorship and surveillance of the IWW during the First World War did not destroy the organisation, which actually reached its peak membership in the early 1920s and still survives into the present. But the federal campaign against the IWW in wartime deprived it of its entire national leadership, its records and correspondence, and even the tools needed for routine administrative tasks, at a crucial time in its history. There is no way to tell whether, in the absence of this concerted and almost certainly unconstitutional attack by the state against a political movement, the IWW might have ever come close to achieving its aim of a society run by the workers for the workers. They might, at least, have imbedded themselves more deeply within the American labor movement. The federal campaign against the Wobblies certainly made sure that neither outcome ever became possible.

At a time when the Espionage Act has again become the tool of choice for dealing with dissent, and when government surveillance of the people has reached levels undreamt of a century ago, the fate of the IWW during the First World is a cautionary tale that we can still learn from today. We should not take from that tale the lesson that radical movements are always destined to be smashed by state repression. It does mean, however, that these movements must be able to exploit divisions within that state if they wish to survive and get what they want. Lenin once wrote that a revolutionary situation occurred when the lower classes did not want to live in the old way and the upper classes could not continue in the old way. The IWW was a revolutionary movement, with revolutionary aims, but it never found itself during the First World War in a revolutionary situation that it had any chance to exploit. The upper classes were very happy to continue in the old way and used any and all means to preserve it. IWWs found themselves instead in a counter-revolutionary situation, pursued by counter-revolutionary forces. The fact that they survived after the war in any form at all is a tribute to the idealism, the determination, and the militancy of Wobblies across the United States and beyond.

Copyright (c) Steven Parfitt, 2016

[1] “US District Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan to the Attorney General,” October 31, 1917. Note: all correspondence cited here is from Melvyn Dubofsky and Mark Naison (eds), Department of Justice Investigative Files: Part 1, The Industrial Workers of the World (University Publications of America, Frederick MD, 1989).

[2] “Charges of Treason in Warrants Served on the Pacific Coast,” The Washington Post, September 6, 1917.

[3] David Montgomery, “The “New Unionism” and the Transformation of Workers Consciousness in America, 1909-22,” Journal of Social History 7:4 (1974), 513.

[4] Joseph McCartin, Labor’s Great War: The Struggle for Industrial Democracy and the Origins of Modern Labor Relations, 1912-1921 (Chapel Hill, 1997), 39.

[5] Robert Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America From 1870 to the Present (Boston, 1978), 116.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Michael R. Belknap, “The Mechanics of Repression: J. Edgar Hoover, the Bureau of Investigation and the Radicals 1917-1925,” Crime and Social Justice 7 (1977), 50; “1918 Report of the Attorney General,” 14 -15. Note: all congressional reports cited here are sourced from the US Congressional Serial Set (Readex). Available at: http://www.readex.com/content/us-congressional-serial-set-1817-1994.

[8] “The Espionage Act.” Available at: http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/espionageact.htm.

[9] “William C. Fitts to Frank Nebeker,” July 30, 1918.

[10] Melvyn Dubofsky, We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World (Chicago, 1969) p505.

[11] “Government Suppresses "Reds" In Many Cities,” The Los Angeles Times, September 6, 1917.

[12] “I.W.W. Indictments Charge Crime Nearest to Treason,” The New York Times, September 19, 1917.

[13] Philip S. Foner, “United States of America Vs. Wm. D. Haywood, et. al.: The I.W.W. Indictment,” Labor History 11:4 (1970), 505.

[14] “High Official Working Here on I.W.W. Cases,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 28, 1917; “The Daily Bulletin of the IWW Defense News Service,” April 8, 1918. The Beef Trust Case was an antitrust proceeding by the Justice Department against an alleged interstate meat monopoly in 1905.

[15] “Affidavit of George S. Murdock at the Chicago District Court,” March 1918.

[16] Goldstein, Political Repression in America, 118.

[17] For Burleson’s battles against a union whose members fell under the wartime administration of the Post Office Department, the Commercial Telegraphers Union of America, see my essay “Whither Industrial Democracy? The Federal Government and Organized Labour in the Telegraph Industry During the First World War,” Journal of American Studies 48:2 (2014), 517-39.

[18] “1919 Report of the Postmaster General,” 112-3.

[19] “William H. Lamar to William C. Fitts,” March 15, 1918.

[20] For a fuller description of the federal censorship and propaganda campaign against the IWW during the First World War see my essay “Bringing the IWW Back In: Industrial Democracy and the Repression of Radicalism in the United States During the First World War,” Socialist History, 46 (2015).

[21] “Frank Nebeker to the Attorney General,” December 4, 1917.

[22] “Frank Nebeker to the Attorney General,” February 21, 1918.

[23] “Attorney General to Charles F. Clyne,” March 18.

[24] For a fuller account of the trial see Philip Taft, “The Federal Trials of the IWW,” Labor History 3:1 (1962), 57-91.

[25] Dubofsky, We Shall Be All, 435.

[26] Patrick Renshaw, The Wobblies: The Story of Syndicalism in the United States (New York, 1967), 229-30.

[28] Ear Bruce White, “The United States v. C.W. Anderson et al.: The Wichita Case, 1917-1919,” in Joseph Robert Conlin (ed), At the Point of Production: The Local History of the IWW (Westport, CN, 1981), 153-60; Clayton R. Koppes, “The Kansas Trial of the IWW, 1917-1919,” Labor History 16:3 (1975), 342-54.

[30] Dubofsky, We Shall Be All, 442-3; David G. Wagaman, “’Rausch Mit’: The I.W.W. in Nebraska During World War I,” in Joseph Robert Conlin (ed), At the Point of Production: The Local History of the IWW (Westport, CN, 1981), 127-31.

[31] For the army-run union that the government set up in the Western lumber camps see Robert Tyler, “The Government as Union Organizer: The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 47:3 (1960), 434-451.

[32] “Isaac Blair Evans to Attorney General Gregory,” December 18, 1918; “Claude Porter to William V. Ray,” December 26, 1918

[33] “Memorandum for the Attorney General by James Finch,” November 28, 1922.

. Copyright (c) Peter Cole, 2015