Implications of powerful DNA-altering technology are too important to be left to scientists and politicians: researchers

by Science in Public

Citizen assemblies are ideal for probing the complexities of genome editing.

Credit: Alice Mollon

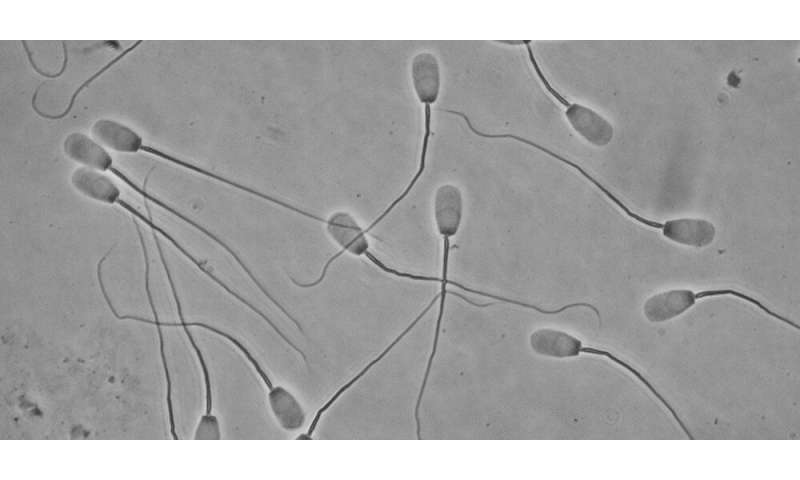

Designer babies, mutant mozzies and frankenfoods: These are the images that often spring to mind when people think of genome editing.

The practice, which alters an organism's DNA in ways that could be inherited by subsequent generations, is both more complex and less dramatic than the popular tropes suggest.

However, its implications are so profound that a growing group of experts believe it is too important a matter to be left only to scientists, doctors and politicians.

Writing in the journal Science, 25 leading researchers from across the globe call for the creation of national and global citizens' assemblies made up of lay-people to be tasked with considering the ethical and social impacts of this emerging science.

The authors come from a broad range of disciplines, including governance, law, bioethics, and genetics.

The immense potential, and threat, of gene editing was vividly demonstrated in 2018, when geneticist He Jiankui announced he had used the technology to create two genetically altered babies.

Dr. He was eventually jailed by Chinese authorities, but his rogue work threw crucial questions about gene-editing humans firmly into the spotlight. How should this technology be used—and who should make those decisions?

The questions go well beyond our own species. Gene editing potentially offers a way to change mosquitoes and wipe out malaria, to boost crop resilience and reduce starvation, or to produce pigs full of organs easily transplanted into humans.

It can also can potentially prevent conditions such as sickle cell disease, cystic fibrosis and even some forms of cancer.

But every good promise, at least in the popular imagination, is mirrored by a bad one: accidentally mutated disease-carrying insects, sterile crops, new treatment-resistant illnesses—and babies engineered for super-strength or musicality.

These implications are so important, believe researchers led by Professor John Dryzek, head of Australia's Center for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance at the University of Canberra, they should be examined not just by those in the field, but by the general public: teachers, plumbers, butchers, bakers and candlestick-makers.

Dryzek and colleagues believe that citizens' assemblies—groups of lay-people tasked with diving deep into the ethical and moral issues thrown up by genome editing—will provide a valuable guide for scientists, doctors and politicians around the world.

"The promise, perils and pitfalls of this emerging technology are so profound that the implications of how and why it is practiced should not be left to experts," Dryzek said.

In the Science paper, the researchers say their proposed global assembly should comprise at least 100 people—none of whom would be scientists, policy-makers or activists working in the field.

The international meeting will take place after several national versions have been conducted. Events in the US, UK, Australia and China are already planned and fully funded by organizations including the Kettering Foundation, National Institutes of Health, the Australian Government Medical Research Future Fund Genomics Health Futures Mission, and the Wellcome Genome Campus.

Projects in Belgium, France, Germany, Brazil and South Africa are also well advanced.

"The fact that they are made up of citizens with no history of activism on an issue means they are good at reflecting upon the relative weight of different values and principles," Professor Dryzek said.

"Think of how we trust juries in court cases to reach good judgements. Deliberation is a particularly good way to harness the wisdom of crowds, as it enables participants to piece together the different bits of information that they hold in constructive and considered fashion."

Citizen-based deliberations are not unusual, as recent plebiscites in Ireland and Australia illustrate. However, the global assembly would be significantly different.

"The issues to be discussed in this assembly are different from the types of issues examined in other forums of this nature—for example, whether same sex marriage should be legalized," said co-author Dianne Nicol, professor of law at the University of Tasmania.

"I don't think the goal of the citizens' assembly should be to answer questions of whether heritable genome editing should be prohibited globally. Rather, it should be about better understanding community concerns and expectations."

It will also be about social justice, added Professor Baogang He, chair of international studies at Australia's Deakin University.

"A global citizens' assembly will help to develop moral and political regulation on genome editing experiments, and to ensure fair access to the technologies," he said.

"It will help global civil society guard against ill use of genome editing for the interest of a few."

Co-author Herve Chneiweiss, Director of UNESCO's International Bioethics Committee and member of the WHO Expert Advisory Committee on the Governance of Human Genome Editing, said the selection process for the global assembly must reflect differences rather than geopolitics.

"Too many people would make a real deliberation impossible, not enough should make it inefficient," he said.

"Our goal should be to be representative. Thus it is not a Senate where each state would get one vote, whatever the number of its population. The '100' should represent the diversity of cultures and origins."

Another co-author, genetic counselor Professor Anna Middleton from Society and Ethics Research, Wellcome Genome Campus in the UK, said new gene-altering practices will eventually impact the whole world.

"For technologies such as genome editing it is crucial to understand social impact," she said.

"The whole globe has the potential to be affected by this, so we must seek representation from as many public audiences as possible across the world."

Professor Dryzek said funding for the global assembly was already well advanced, with funders including the Australian Research Council already on board. He hoped the interest generated by the Science paper would provide a pathway to more.

The planning process and eventually the assembly itself is being recorded by Emmy Award-winning Australian documentary-makers Genepool Productions.

"This is not about providing a speakers platform, rather a thinkers pool," said Genepool creative director and co-author Sonya Pemberton.

"The researchers have come up with a powerful and people-focussed approach to examining a world-changing technology. Capturing this world-first event on film, I hope, will preserve the historic occasion, amplify the global conversation, and provide a template for citizen deliberation on other, equally important matters."

Explore further Report: Heritable genome editing technology is not yet ready for clinical use

Designer babies, mutant mozzies and frankenfoods: These are the images that often spring to mind when people think of genome editing.

The practice, which alters an organism's DNA in ways that could be inherited by subsequent generations, is both more complex and less dramatic than the popular tropes suggest.

However, its implications are so profound that a growing group of experts believe it is too important a matter to be left only to scientists, doctors and politicians.

Writing in the journal Science, 25 leading researchers from across the globe call for the creation of national and global citizens' assemblies made up of lay-people to be tasked with considering the ethical and social impacts of this emerging science.

The authors come from a broad range of disciplines, including governance, law, bioethics, and genetics.

The immense potential, and threat, of gene editing was vividly demonstrated in 2018, when geneticist He Jiankui announced he had used the technology to create two genetically altered babies.

Dr. He was eventually jailed by Chinese authorities, but his rogue work threw crucial questions about gene-editing humans firmly into the spotlight. How should this technology be used—and who should make those decisions?

The questions go well beyond our own species. Gene editing potentially offers a way to change mosquitoes and wipe out malaria, to boost crop resilience and reduce starvation, or to produce pigs full of organs easily transplanted into humans.

It can also can potentially prevent conditions such as sickle cell disease, cystic fibrosis and even some forms of cancer.

But every good promise, at least in the popular imagination, is mirrored by a bad one: accidentally mutated disease-carrying insects, sterile crops, new treatment-resistant illnesses—and babies engineered for super-strength or musicality.

These implications are so important, believe researchers led by Professor John Dryzek, head of Australia's Center for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance at the University of Canberra, they should be examined not just by those in the field, but by the general public: teachers, plumbers, butchers, bakers and candlestick-makers.

Dryzek and colleagues believe that citizens' assemblies—groups of lay-people tasked with diving deep into the ethical and moral issues thrown up by genome editing—will provide a valuable guide for scientists, doctors and politicians around the world.

"The promise, perils and pitfalls of this emerging technology are so profound that the implications of how and why it is practiced should not be left to experts," Dryzek said.

In the Science paper, the researchers say their proposed global assembly should comprise at least 100 people—none of whom would be scientists, policy-makers or activists working in the field.

The international meeting will take place after several national versions have been conducted. Events in the US, UK, Australia and China are already planned and fully funded by organizations including the Kettering Foundation, National Institutes of Health, the Australian Government Medical Research Future Fund Genomics Health Futures Mission, and the Wellcome Genome Campus.

Projects in Belgium, France, Germany, Brazil and South Africa are also well advanced.

"The fact that they are made up of citizens with no history of activism on an issue means they are good at reflecting upon the relative weight of different values and principles," Professor Dryzek said.

"Think of how we trust juries in court cases to reach good judgements. Deliberation is a particularly good way to harness the wisdom of crowds, as it enables participants to piece together the different bits of information that they hold in constructive and considered fashion."

Citizen-based deliberations are not unusual, as recent plebiscites in Ireland and Australia illustrate. However, the global assembly would be significantly different.

"The issues to be discussed in this assembly are different from the types of issues examined in other forums of this nature—for example, whether same sex marriage should be legalized," said co-author Dianne Nicol, professor of law at the University of Tasmania.

"I don't think the goal of the citizens' assembly should be to answer questions of whether heritable genome editing should be prohibited globally. Rather, it should be about better understanding community concerns and expectations."

It will also be about social justice, added Professor Baogang He, chair of international studies at Australia's Deakin University.

"A global citizens' assembly will help to develop moral and political regulation on genome editing experiments, and to ensure fair access to the technologies," he said.

"It will help global civil society guard against ill use of genome editing for the interest of a few."

Co-author Herve Chneiweiss, Director of UNESCO's International Bioethics Committee and member of the WHO Expert Advisory Committee on the Governance of Human Genome Editing, said the selection process for the global assembly must reflect differences rather than geopolitics.

"Too many people would make a real deliberation impossible, not enough should make it inefficient," he said.

"Our goal should be to be representative. Thus it is not a Senate where each state would get one vote, whatever the number of its population. The '100' should represent the diversity of cultures and origins."

Another co-author, genetic counselor Professor Anna Middleton from Society and Ethics Research, Wellcome Genome Campus in the UK, said new gene-altering practices will eventually impact the whole world.

"For technologies such as genome editing it is crucial to understand social impact," she said.

"The whole globe has the potential to be affected by this, so we must seek representation from as many public audiences as possible across the world."

Professor Dryzek said funding for the global assembly was already well advanced, with funders including the Australian Research Council already on board. He hoped the interest generated by the Science paper would provide a pathway to more.

The planning process and eventually the assembly itself is being recorded by Emmy Award-winning Australian documentary-makers Genepool Productions.

"This is not about providing a speakers platform, rather a thinkers pool," said Genepool creative director and co-author Sonya Pemberton.

"The researchers have come up with a powerful and people-focussed approach to examining a world-changing technology. Capturing this world-first event on film, I hope, will preserve the historic occasion, amplify the global conversation, and provide a template for citizen deliberation on other, equally important matters."

Explore further Report: Heritable genome editing technology is not yet ready for clinical use

More information: J.S. Dryzek el al., "Global citizen deliberation on genome editing," Science (2020). science.sciencemag.org/cgi/doi … 1126/science.abb5931

Journal information: Science

Provided by Science in Public

Day one of the mesocosm experiments within the state-of-art experimental wetland facility at Western Sydney University’s Hawkesbury campus - a carp carcass is added to the water. Credit: Ricky Spencer and Claudia Santori.

Day one of the mesocosm experiments within the state-of-art experimental wetland facility at Western Sydney University’s Hawkesbury campus - a carp carcass is added to the water. Credit: Ricky Spencer and Claudia Santori.