GREEN CAPITALI$M

Legal Ease: Towards a green taxonomy

Before the pandemic forced a shift in focus, sustainable investment and the EU’s green agenda was one of the most discussed topics in financial services – and fast becoming an area of fundamental focus for governments and regulatory bodies.

Before the pandemic forced a shift in focus, sustainable investment and the EU’s green agenda was one of the most discussed topics in financial services – and fast becoming an area of fundamental focus for governments and regulatory bodies.

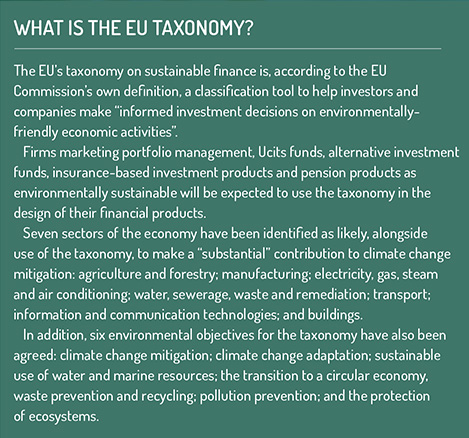

To meet climate targets and transition to an environmentally sustainable economic model, the European Commission had indicated that the EU faced an investment gap. Attracting private capital to the activities that have the highest impact on climate was considered key. It stated: “A shift of capital flows towards more sustainable economic activities has to be underpinned by a shared understanding of what ‘sustainable’ means. A unified EU classification system – or taxonomy – will provide clarity on which activities can be considered ‘sustainable’. It is at this stage the most important and urgent action of this action plan.”

In other words, you cannot mobilise investments towards a greening of the EU before you understand what is green and what is not. This set the scene for a vast and ambitious initiative – to create a way to assess activities and determine whether they are environmentally sustainable.

Political agreement has since been reached on the wording of a regulation on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment – the taxonomy regulation. This is making its way through the European Parliament and is expected to come into force in the summer. The regulation sets out the criteria that needs to be met before an activity can be considered “environmentally sustainable”. It must contribute substantially to one or more environmental objectives or be an enabling activity (‘E’), it must do no significant harm to any environmental objective (‘DNSH’), it must be carried out in compliance with certain minimum social safeguards (‘S’), and it must comply with technical screening criteria.

These are yet to be developed, but will effectively define what it means to “substantially contribute” and “DNSH” to an environmental objective, with the first criteria expected to cover the most urgent environmental objectives: climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation.

The overall regime will require fund managers (among others) to disclose information, including on how and to what extent the investments in their funds support economic activities that meet the criteria for environmental sustainability. And for funds that do not invest in taxonomy-compliant activities, they will essentially need to state that the relevant investments do not take into account the taxonomy regulation.

The EU and member states will have to apply the taxonomy when they adopt measures setting out requirements for financial products or bonds made available as environmentally sustainable. And certain large companies will be subject to related disclosure requirements. However, significant questions remain. Notably, the Commission says an extra €260 billion in investments is needed per year to finance the EU’s green agenda – but it is clear that none of the initiatives announced so far will be sufficient to “move the needle” on that.

Last December, Commission president Ursula von der Leyen described the EU’s Green Deal as “Europe’s man-on-the-moon moment”. The taxonomy regulation will represent a step towards that. Whether it is too little too late remains to be seen.

By Tamara Cizeika, Counsel at Allen & Overy

Sustainable investing: Reaching for a green gold standard

Hopes are high that a landmark EU agreement on how to classify green finance will reduce greenwashing and boost sustainable investing. But, asks Mark Latham, how much difference will the new taxonomy make?

Hopes are high that a landmark EU agreement on how to classify green finance will reduce greenwashing and boost sustainable investing. But, asks Mark Latham, how much difference will the new taxonomy make?

After months of negotiations between EU member states and the European Parliament, agreement was reached in December on what has been called the world’s first regulatory benchmark for green financial products.

The European Commission is hoping that the long-awaited “taxonomy for sustainable finance” will stimulate billions of euros in investment to help the now 27-member bloc achieve its aim of becoming the first continent to reach climate neutrality by 2050.

In the absence of any common minimum legal standards, asset managers have until now largely been free to self-certify and market funds as being environmentally friendly, leaving many investors confused as to what they were actually buying.

A report on greenwashing from London-based wealth manager SCM Direct, published in November, found that definitions of ‘ethical’, ‘socially responsible’ or ‘sustainable’ investing are so loose that funds can effectively invest in whatever stocks they want.

Until the taxonomy – which will cover bonds as well as shares – starts coming into force over the next couple of years, the only independent check on firms’ claims on how sustainable their funds really are will continue to come from ratings agencies, which have over the past decade cashed in on growing demand for ESG scores.

But, while around $3 trillion (€2.7 trillion) of institutional assets globally now track ESG scores, ratings agencies’ role in certifying the green credentials of firms has been criticised for a lack of correlation between the methodologies used to create the ESG scores.

More teeth

Once the taxonomy becomes mandatory, the principal role of checking the green claims of fund houses is likely to move from ratings agencies to national regulators and will gain more teeth in the process. Retail financial products that reach the highest green standards – likely to include investments in clean energy and renewable technologies, for example – will be awarded an eco-label.

Ama Seery, sustainability specialist at Janus Henderson, which manages $374.8 billion in assets, says that the taxonomy is a “welcome first step”, but should have gone further to include not just environmental factors but also social and governance issues.

“Calling it sustainability legislation and then not actually considering all the pillars of sustainable development doesn’t seem right,” she says. “For truly sustainable development to happen, you have to have a balance of all three.”

The taxonomy will help to reduce greenwashing but is unlikely to eliminate it, she says, as clear-cut definitions of ‘transitional’ fuels were sidestepped following lobbying from France and some Eastern European countries. “As a result, we may still see some greenwashing with regards to holdings that are oil and gas-based.”

She adds: “The taxonomy will provide legal definitions of pollution control, so there are lots of areas where it will become against the law to market yourself as doing certain things while not meeting the definitions. This legislation is quite clear that if you have things in your portfolio that are doing environmental harm, then you are not actually a sustainable investment fund.”

From a commercial point of view, Janus Henderson welcomes the legislation, saying it will help flush out investment firms who misclassify and mis-sell ethical investments.

“Greenwashing was bringing firms who were doing this right into disrepute and making all of us look like liars,” says Seery.

Teething troubles

Julie Moret, global head of ESG at $698 billion asset manager Franklin Templeton, frets that there could be short-term teething problems over the application of the taxonomy.

She also questions whether the taxonomy will lead to the reallocation of capital flows towards more sustainable investment activities.

Like Seery, Moret believes that the remit of the taxonomy will eventually have to be broadened to include social and governance factors (the S and the G of ESG). “From an investment decision-maker’s perspective, you look at these elements holistically. You don’t want to just look at the environmental element but want to find out what it took to produce that particular product,” she explains. “That means looking at the whole lifecycle of the product and its global supply chain, which includes corporate governance issues, to understand how each of those components are sustainable.”

Jenn-Hui Tan, global head of stewardship and sustainable investing at $339.2 billion Fidelity International, says that, beyond reducing greenwashing, the taxonomy will benefit the asset management industry by “creating a common language for investors, regulators and companies”.

He says: “One of the challenges of sustainable investing is that inherently ambiguous concepts are used around ESG investing and, until now, there has been a degree of subjectivity in their interpretation.

“We do need a workable definition of what is environmentally sustainable and what is not, but we also have to recognise that a lot of companies are on a transition pathway from an unsustainable to a sustainable business and some companies are at an early stage of that.”

He adds: “As investors, we don’t just want to invest in firms with the highest standards; we want to invest in firms that have an improving trajectory towards those standards and we want to engage with them and help them along.”

Like many of those interviewed for this piece, Leon Saunders Calvert, head of sustainable investing at financial data provider Refinitiv and Lipper Fund Analytics, believes that the taxonomy is “an important step in the process” but doesn’t think it will “solve everything related to sustainability and regulation”.

“This regulation by itself will take some adapting to by the industry,” he says. “For firms to report their revenues according to this taxonomy is not a small thing. There is now a burden on corporates which previously didn’t exist and it will take time, money, cost and a level of expertise and talent which perhaps doesn’t exist today, which firms will have to adapt to.”

Unlike other commentators, Saunders Calvert doesn’t believe that social and governance issues should, at least at this stage, have been included in the taxonomy. “It’s not that the S and G are unimportant, but ESG is a rather awkward bundling together of a lot of disparate and separate issues. We should focus on solving one problem at a time rather than assuming that we have to solve all problems in one go,” he says.

American initiatives

The EU’s move towards establishing a common language for sustainable investing has coincided with a similar push towards greener investing in the US. Last month BlackRock, the world’s largest fund manager, which has been criticised for failing to use its clout to tackle climate change, published recommendations on the terminology of sustainable investing.

It also said it would double the number of sustainability-focused exchange-traded funds it offers to 150 and that it would increase its sustainable assets tenfold to $1 trillion by 2030.

The €7 trillion New York-based firm also pledged, along with other investment firms such as HSBC Global Asset Management, to pressure oil giants and other large industrial and consumer firms to take greater account of their environmental impact.

The move came just days after BlackRock’s chief executive, Larry Fink, used his annual letter to corporations to warn of the increased market risk of climate change and wrote that sustainable investments that take climate change into account will, sooner rather than later, deliver better returns.

Signs of a sea change in attitudes towards ethical investing at a global level became apparent in 2018 when the United Nation’s responsible investment body, the Principles for Responsible Investment, placed one in ten of the signatories to its standards on a watchlist for failing to demonstrate even a minimum standard of responsible investment.

The need for global standards of transparency is stressed by the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, a San Francisco-based non-profit organisation that sets financial reporting standards with a focus on sustainability.

The board’s chief executive, Janine Guillot, says that greater consistency of terminology in the sustainable investing space is needed along with “a need to standardise language around corporate disclosure, product design and labelling in the investment process”.

The board’s chief executive, Janine Guillot, says that greater consistency of terminology in the sustainable investing space is needed along with “a need to standardise language around corporate disclosure, product design and labelling in the investment process”.

She says: “A collective effort across all market participants is needed to ensure investors have the tools and capabilities necessary to achieve their financial goals.

“I think that the direction of travel is positive, but we are still in a messy phase. The good news is that everyone is working toward the same goal, which is how to get more sustainable growth.”

Stanislas Pottier, chief responsible investment officer at Amundi, says in dynamic areas such as sustainable technology, it is important that the taxonomy is efficient and flexible enough to encompass new developments.

“If you are too precise with boxes that are too tiny, then we run the risk of excluding new innovations, so I would tend to prefer a framework that is not too rigid,” he says.

This article first appeared in Funds Europe in February 2020

© 2020 funds europe

Green finance for SMEs to offer “higher yields” for institutions

Amundi is jointly backing a programme to help smaller and medium-sized businesses access green finance and says the debt investments involved will lead to higher yields for investors.

Amundi is jointly backing a programme to help smaller and medium-sized businesses access green finance and says the debt investments involved will lead to higher yields for investors.

The Paris-based asset manager is partnering with the European Investment Bank (EIB), which issued the world’s first green bond in 2007.

Amundi says the partnership will enable smaller companies to access green finance in contrast to the growing green bond market, which has mainly developed by way of issuances from sovereign, quasi-sovereign and large corporate issuers.

The Green Credit Continuum investment programme, as it is called, has three components:

- The creation of a diversified fund that will invest in green high yield corporate bonds, green private debt and green securitised debt.

- In parallel, a scientific committee of green finance experts will be formed to define and promote environmental guidelines for these three markets in line with international best practice and legislation derived from the European Commission action plan on financing sustainable growth.

- A green deal network will be put in place to source deals and projects.

The goal of the agreement is to create several funds based on this model and to help establish market standards. It aims to raise €1 billion within three years, including a €60 million initial commitment by the EIB.

Ambroise Fayolle, EIB vice-president said a “significant financing gap persists and huge potential is still waiting to be tapped in some green debt segments”.

Amundi chief executive Yves Perrier, said: “[The programme] offers a particularly innovative investment solution to institutional investors wishing to help finance the energy transition and diversify their sources of yield in a low interest rate environment.”

He said the programme would combating global warming.

Amundi and the EIB said to meet its climate commitments under the Paris Agreement and finance the associated energy transition, Europe is missing an estimated €180 billion in financing a year until 2030. To reach this level of investment, green finance “must mobilise all of the debt capital markets”.

©2019 funds europe

ESG appears to be passing the scrutiny test with more investors perceiving performance merits.

ESG appears to be passing the scrutiny test with more investors perceiving performance merits. Asset managers see governance as their central ESG factor - but environment and social issues are gaining importance, research shows.

Asset managers see governance as their central ESG factor - but environment and social issues are gaining importance, research shows. Millennial investors who would abandon their ideals surrounding sustainable investing would want a return of 21% to “offset any guilt”.

Millennial investors who would abandon their ideals surrounding sustainable investing would want a return of 21% to “offset any guilt”. Legal & General Investment Management says it will hold a “far more extensive” number of companies to account over climate change.

Legal & General Investment Management says it will hold a “far more extensive” number of companies to account over climate change.  High carbon emitting companies have been called on by investment management firms to commit to a net zero future by setting science-based targets.

High carbon emitting companies have been called on by investment management firms to commit to a net zero future by setting science-based targets.