Draft designs for a planned Nicolas Roeg sci-fi movie in 1979 finally see the light of day

Dalya Alberge Sun 18 Oct 2020

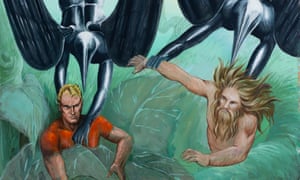

Artwork for the abandoned film depicts Flash Gordon confronting Ming the Merciless on top of the emperor’s royal spaceship. Photograph: StudioCanal/King Features Inc

Flash Gordon fans worldwide can only imagine what might have been. Futuristic artwork – including lots of phallic imagery – that was created for an aborted 1979 feature film about the cult spaceman superhero and his intergalactic adventures is to be published for the first time.

The production was to have been directed by one of Britain’s foremost film-makers, the late Nicolas Roeg, who had made Don’t Look Now, a horror story starring Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland, and The Man Who Fell to Earth, the arthouse science fiction drama starring David Bowie as an alien.

His Flash Gordon film would have starred Debbie Harry, lead singer of the American band Blondie, as Princess Aura, the seductive daughter of Ming the Merciless, the tyrannical dictator, who would have been played by Hollywood movie star Keith Carradine.

Flash Gordon fans worldwide can only imagine what might have been. Futuristic artwork – including lots of phallic imagery – that was created for an aborted 1979 feature film about the cult spaceman superhero and his intergalactic adventures is to be published for the first time.

The production was to have been directed by one of Britain’s foremost film-makers, the late Nicolas Roeg, who had made Don’t Look Now, a horror story starring Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland, and The Man Who Fell to Earth, the arthouse science fiction drama starring David Bowie as an alien.

His Flash Gordon film would have starred Debbie Harry, lead singer of the American band Blondie, as Princess Aura, the seductive daughter of Ming the Merciless, the tyrannical dictator, who would have been played by Hollywood movie star Keith Carradine.

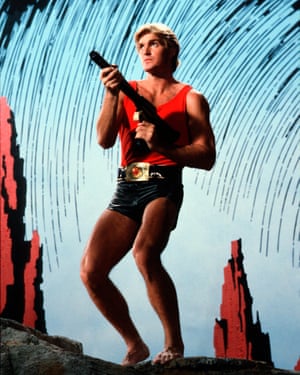

Sam J Jones as Flash Gordon in Mike Hodges’s 1980 film. Photograph: Alamy

But the production was abandoned before Roeg had cast his superhero after he fell out with its producer, Dino De Laurentiis, the movie mogul who made Barbarella, a 1968 science-fiction comic adaptation that turned Jane Fonda into a sex symbol. De Laurentiis had dreamed of three Flash Gordon films. He only made one, the 1980 version directed by Mike Hodges, which became a cult favourite, with huge conventions worldwide despite disappointing reviews.

The film has now been restored by StudioCanal to mark December’s 40th anniversary of its original release.

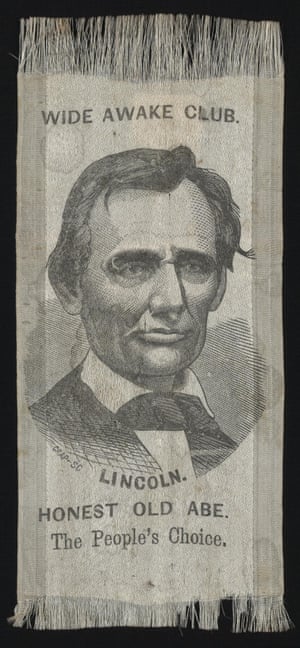

Flash Gordon was originally created by Alex Raymond, the American artist. In 1933, publisher King Features asked him and writer Don Moore to create a rival to the 1929 comic strip Buck Rogers. Flash Gordon made his newspaper debut in 1934 and became an instant hit, read by more than 50 million people a week in 130 newspapers worldwide.

John Walsh, a film-maker and author, has retrieved about 40 designs for the Roeg version from the British Film Institute (BFI) archives: “It’s public knowledge that Roeg worked on the film’s development. What hasn’t been seen is its artwork.”

Walsh will feature the artwork in his forthcoming book, Flash Gordon: The Official Story of the Film, to be published on 20 November.

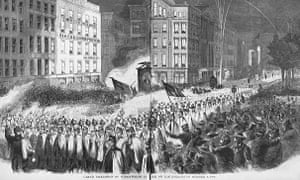

One image depicts Flash Gordon confronting Ming for a sword fight on top of the emperor’s royal spaceship. “It is a vast sequence that could not have been realised using 1970s technology,” Walsh said. “This image has more of the flourish of the original Raymond comic strips from the 1930s.”

The artwork was created by the production designer, Ferdinando Scarfiotti, who went on to win an Oscar for The Last Emperor in 1987.

But most of the imagery suggests a very different film, Walsh said: “It would have been a much more sexually explicit sci-fi romp. Dino chose Roeg, who died in 2018, because he’d worked on The Man Who Fell to Earth, which is science fiction and a very good film, but it’s as far from comic strip melodrama as you could get.”

Ferdinando Scarfiotti’s vision of Arboria dwarfed the actors with giant vegetation and trees. Photograph: StudioCanal/BFI

Of the artwork, he said: “Everything’s quite organic. They look like plants… Ming’s spaceship is the most conventional of the designs, but most of the spaceships are a cross between phallic imagery and orchid flowers, reflecting a more adult tone based on the sexualised imagery of the 1930s strip.

“I interviewed John Richardson, who had worked on its special effects for four months before De Laurentiis pulled the plug. He said, I asked Nic one day ‘what do you see Ming’s spaceship looking like?’ He replied, ‘I see it like a heaving, mucus-covered placenta’ [though that] differs from the design shown.

“Richardson was taken aback because he was expecting something that had much more of a 1930s Chrysler motor look to it.

“Instead, Roeg was taking it in a completely opposite organic direction. In a sense, Dino was right to pull the plug.”