Another byproduct of the pandemic: paranoia

The COVID-19 pandemic increased our feelings of paranoia, particularly in states where wearing masks was mandated, a new Yale study has shown. That heightened paranoia was particularly acute in states where adherence to mask mandates was low, the researchers report July 27 in the journal Nature Human Behaviour.

Increased feelings of paranoia were also associated with greater acceptance of conspiracy theories, the researchers found.

"Our psychology is massively impacted by the state of the world around us," said Phil Corlett, associate professor of psychology and senior author of the study. "From a policy standpoint, it is clear that if a government sets rules, it is important that they are enforced and people are supported for complying. Otherwise they may feel betrayed and act erratically."

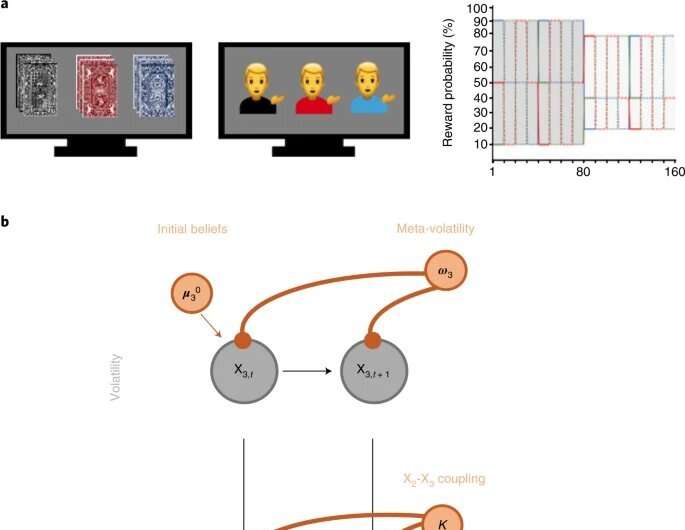

Corlett and his colleagues were already studying the role uncertainty plays in the development of paranoia in individuals as the pandemic began in early 2020. In those early experiments, the Yale team measured the volatility of peoples' choices during a simple card game in which rules could suddenly change, provoking a rise in paranoia for participants. Some people literally thought the deck was stacked against them and changed their choices frequently, even when similar choices had led to beneficial outcomes previously.

"We continued to gather data through lockdown and into reopening," Corlett said. "It was one of those rare, serendipitous incidences where we were able to study what happens when the world changes rapidly and unpredictably."

The baseline data collected on paranoia revealed the psychological impact of the pandemic.

Using online surveys and the same card games, the researchers found increased levels of paranoia and choice volatility among the general population. They also investigated the effect of public health policy choices on peoples' sentiments in states where masks were mandated and those where masks were simply recommended. In their analysis they also evaluated prior research on regional differences in how strongly people feel about following rules.

Paranoia and erratic choice behavior were higher in states where masks were mandated than in those that had looser restrictions. But scores were highest in areas where adherence to the rules were the lowest and where some people felt most strongly that rules should be followed.

"Essentially people got paranoid when there was a rule and people were not following it," Corlett said.

The researchers also found that people who were more paranoid were more likely to endorse conspiracies about mask-wearing and potential vaccines, as well as the QAnon conspiracy theory, which posits, among other ideas, that the government is protecting politicians and Hollywood entertainers who are running pedophile rings across the country.

Corlett said there are many historical precedents for a rise in conspiracy theories during times of trauma, from a prevalent belief that medieval bubonic plague outbreaks were caused by Jews poisoning well water to the "9/11 Truth" movement which contended that the 2001 terror attacks were orchestrated by the U.S. government.

"In times of trauma and great change, sadly, we have a tendency to blame another group," he said.