By Trygve Skogseth

Last updated on34 minutes ago

When Leif Rohlin walked into the locker room for a Saturday training session, the police were there. They told him that his friend and former team-mate had been killed in the street, not far from where he lived.

Rohlin, who had won Olympic ice hockey gold with Sweden the year before and would later play in the NHL, says he can't remember the exact words officers used on that March morning in 1995.

He can't remember whether it was there in the locker room that he learned just how brutal the killing had been, that his friend had been stabbed 64 times.

He can't remember where he was when he first heard that it was a man with ties to a neo-Nazi group who had been arrested, or that police suspected his friend had been killed after making a pass at the man.

What Rohlin does remember is that training got pushed back an hour.

Vasteras had a decisive play-off game the following day. He remembers that there was a minute of silence before the whistle, and that they were soundly beaten.

"It was completely absurd," Rohlin says now. "There were a couple of us out on the ice that knew him well. I think playing the game wouldn't be on the table had it happened today. We would have been given some breathing space."

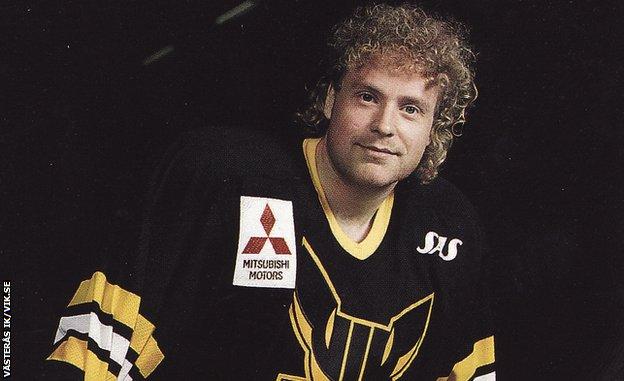

More than two decades have passed since the tragic death of 29-year-old ice hockey player Peter Karlsson. Friends and activists are still angered by the events that followed.

Karlsson never made it home from a Friday night out in spring 1995.

According to court documents, the 19-year-old man who confessed to killing him was a member of a local skinhead group with ties to the neo-Nazi movement. In the three rounds of court cases that followed Karlsson's death - eventually it went all the way to Sweden's supreme court - the defendant maintained that what happened was not premeditated, that he had been "provoked".

He claimed that he bumped into Karlsson on his way back from a night out in Vasteras, a town about an hour's drive west of Stockholm. He said they walked in the same direction for a while, before Karlsson told him he thought he was attractive and forced himself on him by grabbing his head.

In the minutes that followed, the man stabbed Karlsson in his chest, head, face and back. He was left so brutally injured that one of the first police officers on the scene, a man who had coached him as a youth player, didn't recognise him.

There were no witnesses to what happened that night. The court had to rely heavily on the testimony of the defendant, who said that he was stricken by rage and panic. When searching his home, the police had found pamphlets with anti-gay propaganda.

But despite this, and the brutal use of force, the supreme court upheld the original verdict; it was manslaughter, rather than murder. The killer was sentenced to eight years in prison

The morning after Karlsson's death, the phone rang at the home of Sweden's national ice hockey team manager, Curt Lundmark. He took the call sitting at his kitchen table, just up the road from where Karlsson had grown up.

Lundmark had led Sweden to their legendary first Olympic gold medal at the Lillehammer Winter Olympics of 1994. Before that, he had coached Karlsson as a youth player in Vasteras for the better part of a decade.

"I just sat there in shock, trying to process what I had heard," he says.

"Peter was the kind of guy who, if he saw you were home, he'd stop by and take the time to strike up a conversation. The type who made everyone around him smile."

Lundmark followed the case closely as it made its way through the Swedish justice system. To this day, the way Karlsson was portrayed in the courtroom bothers him. He has always believed that the verdict was wrong.

"I don't think the courts got to hear enough about what type of guy Peter actually was," he says, adding that they would have a hard time finding anyone in Vasteras who wouldn't describe him as harmless.

"They just relied on the story that his killer told them."

Dennis Martinsson, an assistant professor and expert in criminal law at Stockholm University, is of the same opinion. In his view, details such as the anti-gay literature found at the killer's home were not given proper consideration either.

But he says that there has been real progress in recognising hate crimes against minorities in Sweden

In the 1980s and 1990s, the country saw a series of killings of gay men. Facundo Unia, a gay rights activist in Stockholm, covered some of these as a journalist. He believes that the so-called 'gay panic' defence proved an effective way for many defendants to get more lenient sentencing for what he considers to have been hate crimes.

That legal strategy - where defendants argue they were provoked by an unwanted same-sex sexual advance - is still admissible in many parts of the world. According to a 2021 report by the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law in the United States, "gay and trans panic defences remain available in most states".

In the UK, the tactic is thought to have declined since 2003, when the Crown Prosecution Service published guidance on its "proactive approach" towards "homophobic or transphobic crime".

In Unia's opinion, the general sentiment towards gay people in the '90s meant there was less sympathy for the victims in these cases, leading the court to go easier on the perpetrators.

"There is an attitude of 'that gay guy came on to me, I just had to get rid of him' in these defences," Unia says.

Walking up the quiet residential street where Karlsson was killed, not far from Vasteras city centre, his former team-mate Rohlin points towards an empty spot in front of one of the houses.

"There used to be a plaque commemorating what happened right here. I don't know why they took it down," he sighs.

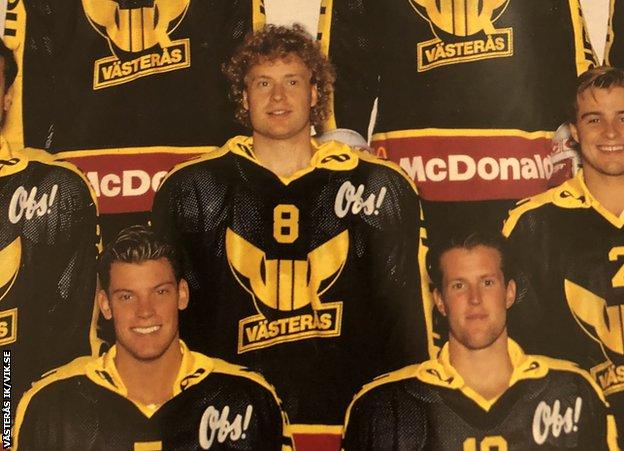

Karlsson belonged to a generation of young players from Vasteras who would go on to make a big impact on Swedish ice hockey. Three of those who claimed Olympic gold at the Lillehammer Games of 1994 were friends and former team-mates.

"It was a terrible call to get," says Patrick Juhlin, who learned the news of Karlsson's death while playing for the Philadelphia Flyers in the NHL.

"The first question is just why and how such a thing could have happened. It ended up being quite a few phone calls."

Karlsson was a couple of years older than both Juhlin and Rohlin. When they joined the youth development team in Vasteras, he was one of the players they looked up to.

"He was the first guy you'd invite to a party," Rohlin says. "There was never even an inch of bad intention in that guy. He was just joy and cheer all the way through."

In the months following Karlsson's death, Rohlin kept himself busy preparing for the World Championship that Sweden was about to host. Lundmark, the coach, instructed his team to not read the evening papers or watch the extensive coverage the killing was getting.

"I figured it was best to try to put it behind us and focus on the game as best we could," he says. In the middle of the team's preparations, he left with three of his players to attend Karlsson's funeral in a packed church in Vasteras.

For Karlsson's friends, the press reports that he had been killed after making a pass at another man came as a shock. Karlsson was not openly gay. According to court documents, he had discussed being gay with a couple of guests at the nightclub he had been at the night before he was stabbed. As for his friends, it was not something he ever brought up.

"If he was gay, and he just never felt able to talk to us about it, that pains me," Rohlin says.

"It's tragic in and of itself. We would have pretty deep conversations. That he wouldn't have told us feels unbelievable, given the way we knew each other."

Karlsson's team-mates have now long retired from professional ice hockey. Standing in front of a small grey tombstone in a graveyard outside Vasteras, Rohlin says his friend's death still troubles him enormously, 26 years on.

He adds: "If the verdict had been 12 or 24 years in prison, it wouldn't really matter much either way.

"It won't bring Peter back."