Beanless brews can cut deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions dramatically – but what will happen to workers in traditional coffee-growing regions?

Supported by

Nadra Nittle

Sat 16 Oct 2021

Heiko Rischer isn’t quite sure how to describe the taste of lab-grown coffee. This summer he sampled one of the first batches in the world produced from cell cultures rather than coffee beans.

“To describe it is difficult but, for me, it was in between a coffee and a black tea,” said Rischer, head of plant biotechnology at the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, which developed the coffee. “It depends really on the roasting grade, and this was a bit of a lighter roast, so it had a little bit more of a tea-like sensation.”

Rischer couldn’t swallow the coffee, as this cellular agriculture innovation is not yet approved for public consumption. Instead, he swirled the liquid around in his mouth and spit it out. He predicts that VTT’s lab-grown coffee could get regulatory approval in Europe and the US in about four years’ time, paving the way for a commercialized product that could have a much lower climate impact than conventional coffee.

The coffee industry is both a contributor to the climate crisis and very vulnerable to its effects. Rising demand for coffee has been linked to deforestation in developing nations, damaging biodiversity and releasing carbon emissions. At the same time, coffee producers are struggling with the impacts of more extreme weather, from frosts to droughts. It’s estimated that half of the land used to grow coffee could be unproductive by 2050 due to the climate crisis.

In response to the industry’s challenges, companies and scientists are trying to develop and commercialize coffee made without coffee beans.

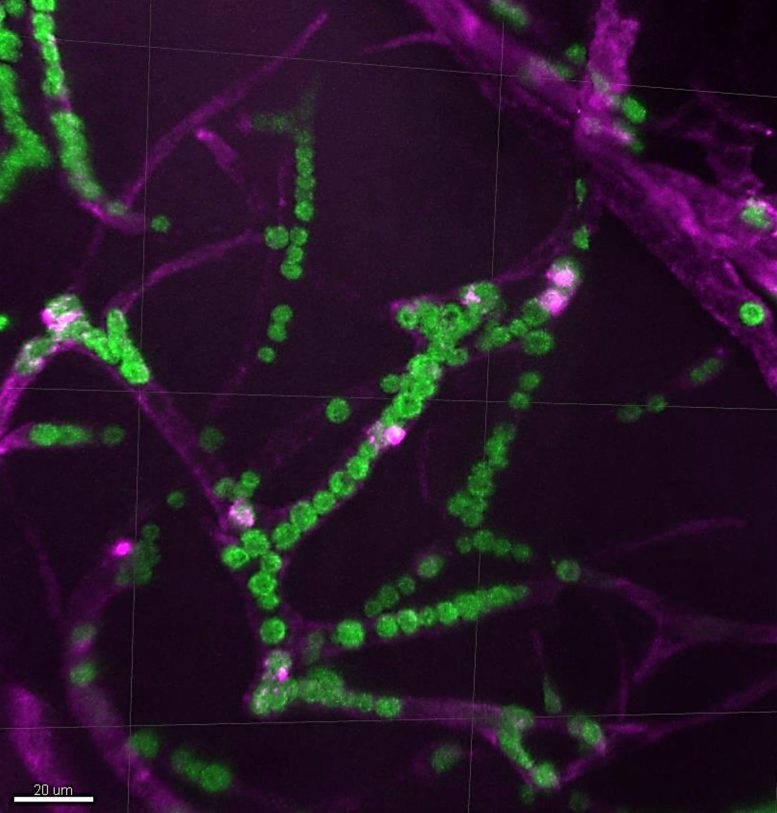

VTT’s coffee is grown by floating cell cultures in bioreactors filled with a nutrient. The process requires no pesticides and has a much lower water footprint, said Rischer, and because the coffee can be produced in local markets, it cuts transport emissions. The company is working on a life cycle analysis of the process. “Once we have those figures, we will be able to show that the environmental impact will be much lower than what we have with conventional cultivation,” Rischer said.

American startups are also working on beanless coffee. In September, Seattle-based Atomo Coffee released what it called the world’s first “molecular coffee” in a one-day online pop-up, charging $5.99 a can.

The startup, which has raised $11.5m, makes its coffee by converting the compounds from plant waste into the same compounds contained in green coffee. Ingredients, including date seed extracts, chicory root, grape skin as well as caffeine, are roasted, ground and brewed. This method results in 93% lower carbon emissions and 94% less water use than conventional coffee production, as well as no deforestation, according to Atomo.

“The industry has known about the deleterious effects of coffee farming for a long time, whether we’re talking deforestation or major water usage,” said Atomo’s co-founder Jarret Stopforth. “[Before starting Atomo] I was thinking to myself, ‘There’s got to be a better way to do this.’”

Atomo’s facility can produce about 1,000 servings of coffee a day. The goal is to increase that to 10,000 servings a day over the next 12 months, said Stopforth, and in two years to move into a facility that can produce 30m servings of coffee a year. Stopforth says that Atomo will start the initial phase of the new factory build within the next three months.

Alternative coffee companies like Atomo not only have the potential to help tackle the climate crisis but to benefit the industry generally, said Sylvain Charlebois, a professor in food distribution and policy at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Take arabica beans, said Charlebois. “You need specific climatic patterns, and it’s much better if you’re more in control in a laboratory environment than just trying to rely on Mother Nature.” Technology can help stabilize production and make it more predictable, he said.

But it’s unclear how many people would be willing to give up conventional coffee for one of its beanless counterparts. A 2019 survey by Dalhousie University found that 72% of Canadians say they would not drink lab-grown coffee.

Maricel Saenz, founder and CEO of San Francisco-based Compound Foods said she was working to “reinvent” coffee and to show people why doing so matters. Compound Foods, which has secured $4.5m in seed funding, says it recreates coffee farm production in the lab. The startup uses microbes and fermentation technology to grow a variety of flavors and aromas, Saenz said.

Preliminary results from a carbon life cycle analysis indicate that the company’s coffee produces a tenth of the greenhouse gas emissions and water use of traditional coffee, Saenz said. She plans to introduce her product by late 2022 and expects pricing to be similar to specialty coffees. “As we improve our processes, we aim to decrease our prices,” she said.

As the population grows and pressure increases on natural resources, Saenz said, “we need to be producing food in more efficient ways, using a lot of the biotechnology and fermentation tools that are now at our disposal.”

But Daniele Giovannucci, president and co-founder of the Committee on Sustainability Assessment, a consortium that focuses on agricultural sustainability, is concerned that scaling up lab-grown coffee could affect the livelihoods of the millions of workers in the traditional coffee industry, especially in countries such as Ethiopia where coffee is central to the economy. “What’s going to happen to all these people?” Giovannucci asked. “What are they going to do, because this is a key cash crop?”

There’s a risk, he said, that lab-grown coffee could create significant socio-economic problems that could drive even greater climate change effects. “It is not clear if, in the end, its net effect may worsen global sustainability, along with many millions of lives.”

Saenz, who is from Costa Rica, a coffee-exporting country, said, “I know many coffee producers, so it’s something that I definitely worry about.” But, she added, “the number one threat that coffee farmers have today is climate change” – whether that’s heat that disrupts ripening times, or unexpected frosts as Brazil experienced in the summer, which severely damaged crops.

Saenz said her company will collaborate with non-profits to support small coffee farmers transitioning to more sustainable agricultural practices, including providing training and crop insurance.

While lab-grown coffee shows real promise, said Charlebois, the politics should not be underestimated, especially as so many farmers depend on conventional methods of producing crops and many of them live in developing economies. “Scalability is not an issue for lab-grown coffee,” he said, “but regulations and general acceptance of the technology will be greater challenges.”