The Cult of Ideology vs. The Cult of Personality

The most important clashes aren’t between right and left but within right and left

| 10 |

Do you ever read an idea and feel enlightened and envious at the same time? You simultaneously think, “Aha! That’s insightful,” and “Dang! I’ve been sniffing around this concept and haven’t quite nailed it like he did.” In this instance, it’s a concept that helps explain both the deep dysfunction of our political system and the deep discomfort that so many people of good will—on both sides of our political spectrum—feel with our political culture.

It’s summed up in this tweet by a sharp lawyer I follow who tweets under the name “A.G. Hamilton.”

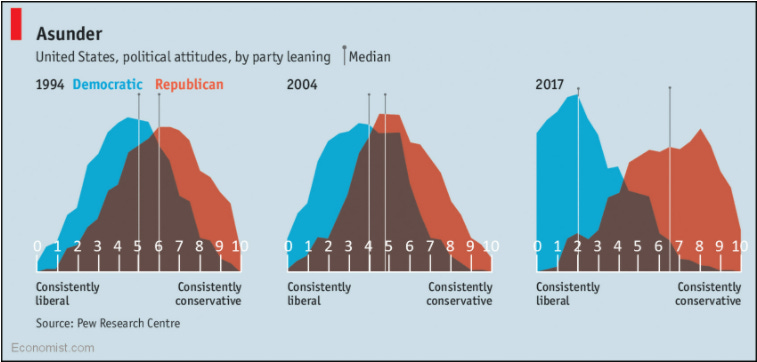

If you click on the tweet you can read his entire thread, but his point rests on two key and obvious trends. First, the Democratic Party has moved quite decisively to the left, and the median Democrat has moved far more to the left than the median Republican has moved to the right. This chart, recently made famous in a column by progressive writer Kevin Drum, illustrates the point nicely:

And as millions upon millions of Americans have moved collectively to the left—especially when those Americans are disproportionately clustered in like-minded urban enclaves—they have become increasingly intolerant of dissent. Although there are signs that at least some of the cancel culture fever is breaking, I like what Drum says to those who refute its existence:

And for God’s sake, please don't insult my intelligence by pretending that wokeness and cancel culture are all just figments of the conservative imagination. Sure, they overreact to this stuff, but it really exists, it really is a liberal invention, and it really does make even moderate conservatives feel like their entire lives are being held up to a spotlight and found wanting.

Yup. Exactly. We can disagree about the extent of American cancel culture—or whether any given event qualifies—but to deny its existence is to engage in willful partisan blindness.

Lots of folks on the right forwarded around and commented on Drum’s post last summer (it was provocatively titled, “If you hate the culture wars, blame liberals”). Thoughtful conservatives asked their progressive friends to look at the data and examine whether their movement was becoming unacceptably extreme, fueled by the kind of radicalizing frenzy that we so often see from ideologically homogeneous communities.

In fact, as I wrote in my most recent book, Divided We Fall, this phenomenon was explained and predicted by Cass Sunstein almost a generation ago. In a 1999 paper called “The Law of Group Polarization,” he explains that when like-minded people gather, they tend to grow more extreme. Or, here’s how he put it in more academic language:

In a striking empirical regularity, deliberation tends to move groups, and the individuals who compose them, toward a more extreme point in the direction indicated by their own predeliberation judgments. For example, people who are opposed to the minimum wage are likely, after talking to each other, to be still more opposed; people who tend to support gun control are likely, after discussion, to support gun control with considerable enthusiasm; people who believe that global warming is a serious problem are likely, after discussion, to insist on severe measures to prevent global warming.

“This general phenomenon—group polarization—has many implications for economic, political, and legal institutions,” He wrote. “It helps to explain extremism, ‘radicalization,’ cultural shifts, and the behavior of political parties and religious organizations; it is closely connected to current concerns about the consequences of the Internet.” (Emphasis added.)

Remember, this was written in 1999, before The Facebook was a gleam in Mark Zuckerberg’s eye.

But Hamilton’s tweet captures something that Drum’s chart doesn’t—the nature of radicalization on the right. Any fair reading of the right’s ideology would include the phrase “deeply confused.” After all, where does disproportionate resistance to vaccines come from? That wasn’t even on the right-wing radar before 2020, and to the extent that conservatives cared, they mainly saw it as a product of the crunchy, green weird left, not the populist right.

Right-wing ideology is so up for grabs that it’s hard to know “the right’s” position on everything from the size and role of government, the First Amendment (for example, it’s somewhat fashionable now for Republican governors to sign obviously unconstitutional bills regulating corporate speech), and foreign policy. After all, the right’s top cable host is now openly echoing the Kremlin’s line in its looming conflict with Ukraine.

The right’s cult is different. Hamilton calls it a cult of personality. That can imply “Trump,” but I think it’s deeper (and Hamilton notes that it’s deeper). It’s a cult of a certain type of personality, one that is relentlessly, personally, and often punitively aggressive. The aggression is mandatory. The ideology is malleable.

And don’t think for a moment that this began with Trump. He both channeled and amplified a pre-existing tsunami of outrage and animosity. Years back, well before I entered the world of journalism full-time, I spent considerable time, energy, and effort trying to help Mitt Romney win the presidency. My wife and I formed a group called “Evangelicals for Mitt” designed to help persuade my fellow Evangelicals that the Mormon former governor of Massachusetts was the best man for the world’s most difficult job.

In our conversations we emphasized his integrity, his decency, and his competence. Talk about missing your audience—turns out that each of those virtues turned out to be less important than pugilism or aggression.

But even then, the message from much of the grassroots was clear. Hit harder. No, hit even harder. Lack of aggression was perceived as lack of effort, a lack of a will to win. Mitt’s primary competitors weren’t necessarily more conservative than him, but they were more aggressive.

What we now call “Trumpism” is really Trump’s imprint on an impulse that pre-existed Trump and is likely to persist well past his presidency. If you pay little attention to talk radio, you’re likely missing the extent of devotion to the cult of aggression.

The same thing goes for the top-rated television shows and websites. The same personality characteristics persist. It’s pugilists almost all the way down. Reasoned voices are hard to find. And when I say “pugilists,” there is almost no limit to the rhetoric. In a recent New Yorker profile of Dan Bongino—one of social media’s most prominent right-wing voices—Evan Osnos quotes him as describing “insane leftists” as people who “wish death on me and everyone else from COVID, because they’re legitimately crazy satanic demon people.”

That’s absurd rhetoric. Just absurd. But words like “evil,” “satanic,” and “demonic” are routinely thrown around to describe political opponents. Write something that the Trump right disagrees with (especially on matters of race), and you’re “loathsome,” “despicable,” and “odious.” I oughta know, those words were written about me.

Hamilton optimistically argues that the right will be less difficult to reform because the cult of personality is driven by the search for a “winner.” Change the identity of the winner, and you change the nature of the cult. I hope he’s right. While I don’t like the cult concept in general, I could at least sip the Kool-Aid in a cult of Sasse, but I’m dumping out the entire glass of Trump.

Unfortunately, however, there is now evidence that parts of the right might “move on” from Trump by becoming more aggressive than Trump. Alex Jones (don’t laugh, he has a huge following) has threatened to turn on Trump for pushing the COVID vaccine. Candace Owens (again, another person with a huge following) has also sharply disagreed with Trump on vaccines, suggesting Trump is too old to follow the latest “independent research.”

Most notably, Florida governor Ron DeSantis, arguably the leading contender for post-Trump Republican leadership has triggered a feud with Trump by being evasive about his vaccine status and criticizing the president’s early handling of the pandemic as too draconian. And don’t forget he recently signed a bill in Brandon, Florida—an obvious nod to the right-wing “Let’s go Brandon” slur.

The existence of these two cults does much to explain why so many Americans feel so deeply alienated and conflicted about American politics. They explain why so many of us should feel alienated and conflicted. You can take the most thoughtful and committed Christian socialist or progressive (and I know more than a few), and even those folks who might welcome greater awareness of systemic injustice and profound income inequality are deeply chagrined at the package-deal ethics that come with increasing extremism.

“Do I really have to affirm that a man can get pregnant, or that there are no true biological distinctions between men and women?”

“Do I have to support taxpayer funding of abortions?”

“Do I have to forsake race consciousness (awareness of the profound and systemic injustice) for a kind of intolerant race essentialism that seems to not just speak profoundly untrue things but also violates the civil rights of American citizens?”

At the same time, you can take the most thoughtful and committed Christian pro-life and religious liberty activist, a person who has spent their entire life seeking uphold and advance values of decency, integrity, and fidelity and face the following questions:

“Do I really have to move on from, minimize, or rationalize a violent effort to overturn a presidential election?”

“Should I keep my thoughts about a lifesaving vaccine to myself to avoid fracturing my political coalition even when people I know and love are dying tragic and needless deaths?”

“Is even the idea that this nation bears responsibility for addressing the continued consequences of centuries of racist oppression too ‘woke’ to speak?”

“Is loving my enemies now naïve? Does exhibiting the fruits of the spirit—even in politics—mark me as weak?”

When mutual animosity escalates—and when that gap between red and blue in the chart above widens—the temptation to overlook these internal fault lines can become overpowering. Indeed, the primary reason why 2019’s “against David-Frenchism” essay (which argued that my classical liberal philosophy and personal manner were uniquely problematic to the new right) went viral wasn’t because of its attack on the classical liberalism of the American founding. That’s still a fringe idea that would shock Republican Americans who revere the founders and the founding documents.

No, it was the attack on decency and civility as “secondary values.” Here was a Christian rationalizing the sidelining of clear and unequivocal biblical commands—commands written when political enemies were far more deadly and the church far more vulnerable than it is today.

The most important cultural clashes in America in the present moment aren’t between right and left but rather within right and left. They’re aimed at arresting the present trends that render public life increasingly miserable and our union increasingly fragile.

And here’s where the hope lies. There is evidence of increasing awareness on the left that the movement has simply gone too far. From London Breed’s crackdown on crime in San Francisco to Eric Adams’s election in New York City, there is increasing evidence that regular voters are starting to reject the dangerous extremes. “Defund the Police” is a dead slogan, relegated back to isolated corners of Twitter and small parts of the academy.

And what of the right? I keep going back to the spiritually and culturally consequential 2021 Southern Baptist Convention. At a crucial moment when a “conservative” movement that all too often mirrored aggression and pugilism of the political right tried to seize control of the SBC, other conservatives (this was no moderate v. conservative contest) answered that they, in the words of former SBC president J.D. Greear, are “great commission Baptists. We have political leanings. But we are not the party of the elephant or the donkey. We are the people of the lamb.”

They elected as president Ed Litton, a man known as a pastor, not a culture warrior, and who has engaged in faithful and consistent efforts at racial reconciliation.

We can and should find purpose and meaning in our discontent, in our sense that we don’t truly “fit” with either of America’s most aggressive political and cultural factions. It’s that discontent, given voice and put into practice, that can rescue us from the cults of ideology and personality, the movements that are ripping our families, our communities, and our nation apart.

One more thing …

I originally envisioned the Good Faith podcast as an extension of the discussions in this newsletter, but the podcast comes out before I write, so that’s not always going to work. This week is no exception. Curtis and I take a hard look at why pastors are leaving churches, what that says about us, what that says about the church, and what we can do about it.

Please listen to the whole thing. Curtis is a former pastor, and his story about why he left the pulpit echoes powerfully with pastors who write to me almost every day.

One last thing …

I’ve shared this song before, but I think it’s particularly salient this week, mainly because of the first line—“I’m done trusting in what’s sinking. These boats weren’t built for me.” These political movements that command our loyalty and commitment? Those boats weren’t built for us.