The Wall Street Journal: The Once & Future Drug War

The following is the direct text of an article that was written by journalists James Marson, Julie Wernau, and David Luhnow for the newspaper The Wall Street Journal and released on January 21, 2022.

During the 50 years the U.S. has battled the narcotics trade, illegal drugs have become more available and potent. But that’s no reason to give up. Governments must adapt and find answers beyond law enforcement.

America’s longest war isn’t the 20-year fight in Afghanistan. That struggle is dwarfed by the War on Drugs, started by President Richard Nixon more than 50 years ago and still raging.

|

| President Nixon after signing a drug bill in Washington, Oct. 27, 1970. PHOTO: ASSOCIATED PRESS |

The drug war—which has relied on both law enforcement and the military, at a cost of untold lives and hundreds of billions of dollars—has fared little better than the Afghan campaign. Since Nixon’s declaration of war in 1971, drug use has soared in the U.S. and globally, the range and potency of available drugs has expanded and the power of criminal narcotics gangs has exploded.

At the current rate, accidental drug overdoses are killing some 100,000 Americans annually, and those deaths have roughly doubled every decade since 1979. Law enforcement is now focused not only on the deadly opioid fentanyl but on a surge of new, stronger methamphetamines, capable of giving users mental disorders in just a few days. In Europe, cocaine seizures have hit record volumes, and Europe may now be a bigger market for cocaine than the U.S., according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

As one popular saying has it: We declared war on drugs—and drugs won.

Many drug policy experts and veterans disagree. They say that the failures of the past half century don’t mean it’s simply time to give up. The rising potency of synthetic drugs makes it even more urgent to keep them off the streets, and growing encampments of drug users in cities like San Francisco and Seattle show that tolerance is no panacea. As drug gangs adapt and globalize, countries need to adopt new approaches to attack supply, curb demand and treat the problem not only as a policing issue but also as a public health crisis. The COVID pandemic may subside, but the drug epidemic endures and is getting worse.

“The drug war failed not because we treated it as a law-enforcement problem but because we only treated it as a law enforcement problem,” says Sam Quinones, a journalist and author of two books on the U.S. drug crisis. Mr. Quinones is wary of “silver bullet” solutions like outright legalization. He advocates a community approach that blends law enforcement, public health and prevention: Call it compassionate prohibition.

Today, drug-trafficking revenues in places like Mexico fund increasingly sophisticated and dangerous gangs that rival the government in firepower, collect their own taxes through widespread extortion, and even run welfare programs to win social support. Organized crime is rising across Europe, leading to gangland hits in once-peaceful countries such as the Netherlands and Belgium. Abundant narco-cash is even flooding into cities never before known as drug havens, from Antwerp to Dubai.

The global spread of synthetic drugs like methamphetamine, fentanyl and synthetic opioids is complicating interdiction—the core of America’s strategy for 50 years.

|

| A Mexican soldier stands guard in a poppy field before it is destroyed in a military operation, Coyuca de Catalan, Mexico April 18, 2017. PHOTO: HENRY ROMERO/REUTERS |

Narcotics once originated in a handful of regions where their source plants could grow: marijuana in Mexico, coca in Colombia, opium poppies for heroin in Afghanistan. They required large-scale agriculture, which governments could target for eradication. The drugs, often bulky, then moved along known trade routes.

That model is changing. The new synthetics can be manufactured almost anywhere, using easily obtainable chemicals. Tiny amounts are enormously powerful and profitable. Those innovations simplify trafficking and undermine policing. All the fentanyl entering the U.S. annually could fit into 15 or 20 cars, says Daniel Ciccarone, a professor of family medicine at the University of California at San Francisco who has researched street-based drug use for two decades. An estimated 200,000 vehicles cross the U.S.-Mexico border daily.

“Trying to stop drugs coming into the U.S. was always a bit like looking for a needle in a haystack. But now the needle is so much smaller,” says Victor Manjarrez, a former high-ranking Border Patrol officer. Mr. Ciccarone goes a step further: “It’s the angel on the head of the pin in the proverbial haystack.”

Not that crop-based drugs are disappearing. Even as cocaine use in the U.S. falls, Colombia produced a record amount of cocaine in 2020, according to the U.N., as traffickers targeted newer markets from Europe to Australia, where cocaine fetches a far higher price than in the U.S.

Globalized commerce using ubiquitous shipping containers also means that drugs can piggyback on legitimate cargo. Cash-rich traffickers are even testing new technologies like drones and building ocean-crossing narco-submarines.

A paradox of the war is that while drugs have claimed far more lives than terrorists, Western societies have changed far less in response to narcotics. Bombings or shootings linked to the drug trade elicit little reaction because people believe drug gangs exist in a vacuum, Belgian Federal Prosecutor Frédéric Van Leeuw recently told France’s Le Monde. “If the person shouted, ‘Allahu akbar!’ it would not be the same.”

|

| A U.S. Customs and Border Protection canine team checks cars for contraband at the border, San Ysidro, Calif., Oct. 2, 2019. PHOTO: SANDY HUFFAKER/AFP/GETTY IMAGES |

The War on Terror changed how we fly, submit to government monitoring and report our finances. The War on Drugs, by contrast, hasn’t even prompted notable changes at cargo ports, where tighter screening would have far less impact on the daily lives of voters and taxpayers than the intrusive security measures introduced since 9/11 at airports, train stations and office buildings.

Meanwhile, many countries that the U.S. relies on in the drug war have grown tired of the mounting body count and pervasive corruption. Since 2006, Mexico’s efforts to tackle cartels by arresting or killing cartel leaders has backfired: New leaders have simply emerged, and power struggles led to an estimated 250,000 dead in drug-fueled violence. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador seems to have largely given up, calling his strategy of not chasing kingpins “hugs, not bullets.”

So what can be done, since every potential solution has major downsides? A first step, say veterans of the cause, is to see it as an ongoing fight to limit damage, not as a war to be won once and for all.

U.S. policy for 50 years has focused on law enforcement. The result: Supply has grown while the American prison population has exploded.

Increasingly, governments are trying to reduce harm from drug use rather than to eradicate it. Advocates for policies and programs that treat substance use more as a chronic disease than a crime say the growing toxicity of drugs is one of the greatest current public health threats. The primary goal, they say, must be saving lives.

|

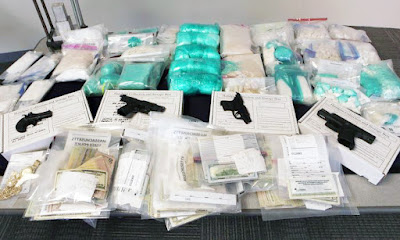

| Guns, drugs and money seized in Boston, Mass, June 20, 2019. PHOTO: NANCY LANE/THE BOSTON HERALD/ASSOCIATED PRESS |

Fentanyl has now killed far more Americans than all U.S. conflicts since World War II combined. In the past decade, it has claimed more than a half million lives, a toll that is growing swiftly. The nation was reporting fewer than 50,000 fatal overdoses as recently as 2014. Nearly half of drugs tested by the DEA contain a potentially fatal dose of the synthetic opioid.

Fentanyl is up to 50 times more powerful than heroin but is far cheaper to manufacture, which makes it lucrative for cartels, boosting their profit margins. They use it as a substitute for heroin powder or press it into black-market oxycodone pills. Fentanyl is now also finding its way into cocaine and party drugs like ecstasy and is even sprayed on marijuana. But what’s good for cartels is often lethal to users.

|

| A man prepares an injection at the OnPoint NYC safe use site in Harlem. Dec. 2021. PHOTO: SCOTT HEINS |

In November, New York City opened the nation’s first overdose prevention centers, where people can consume illegal drugs under supervision. Drug users can have their supply tested for fentanyl and in the event of an overdose, staff can administer the antidote naloxone. The sites can also help with housing, medical care and treatment.

Rhode Island, Massachusetts and San Francisco plan similar centers. The Trump administration challenged them under federal law, but the Biden administration hasn’t said if it will do the same. Absent a federal challenge, more centers are expected.

The Biden administration is the first to name “harm reduction” a priority. The White House Office on National Drug Control Policy, which was often run in the past by former generals and law-enforcement officials, is now led, for the first time, by a physician, Dr. Rahul Gupta.

Some cities are also rethinking how they operate 911 emergency systems. Many drug users, particularly in minority communities, won’t call to report a drug emergency over fears of criminal consequences or police violence. Several cities are testing new formats that involve sending trained mental-health and harm-reduction professionals to such calls alongside police or instead of them.

Europe is also pursuing harm reduction. The U.K., the Netherlands, Austria and others have offered drug testing, often at music events, to reduce the risk of overdosing or poisoning. Switzerland, the U.K., Germany and the Netherlands prescribe heroin to dependent users to cut fatal overdoses and needle sharing.

Portugal has gone further. It decriminalized all drugs in 2001 amid a surge in heroin use and drug-dependent prisoners. Anyone caught with less than a 10-day supply of any drug is sent to a local commission that includes a doctor, lawyer and social worker for treatment. Overdose deaths have fallen from about 360 a year to 63 in 2019.

Health experts can bring fresh approaches. Decades of research have found that programs encouraging users to quit cold-turkey often have worse outcomes than doing nothing. Most U.S. prisons—where some 65% of inmates have a substance-abuse disorder—still use this treatment, which vastly increases chances of a prisoner’s overdose death following release.

Only medication-assisted-therapy—such as treatment with opioid agonists—has been shown to yield better outcomes for drug users, but it is still difficult for many addicts to get access to those medications. Vermont last year decriminalized buprenorphine, a drug that has been found to reduce cravings for addicts but is less potent than methadone or heroin. Funding for such treatments, however, remains a fraction of the broader fight.

Experts also say there is a frustrating lack of data on drug use that could provide answers to basic questions like why dealers or users mix fentanyl with other drugs. In 2013, the U.S. stopped funding a program that surveyed inmates on drug use and helped to identify emerging hot spots as well as new drugs, according to Beau Kilmer, director of the Drug Policy Research Center at Rand Corp.

“Our data infrastructure to monitor this problem is extremely weak,” he says. “With so many people dying, federal agencies and foundations should make this a priority.”

A health-based approach has limits, however, according to Keith Humphreys, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University and an addiction expert. He advocates keeping drugs illegal, noting that legal alcohol and tobacco still kill many more people than illegal drugs. “Do you want tobacco companies to sell fentanyl?” he asks.

|

| A homeless encampment in Venice, Calif., June 30, 2021. PHOTO: FREDERIC J. BROWN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES |

Prof. Humphreys believes that tolerance has helped to feed a growing population of tent encampments often populated by drug users in cities on the West Coast, including Venice Beach, Calif., which some locals jokingly call “Methlehem.”

Removing social or legal disapproval of drug use doesn’t seem to boost recovery, he says. In Oregon, drug users receive a $100 fine that they can get waived by agreeing to a 20-minute call with social services to encourage them to enter a treatment program. Fewer than 1% have sought treatment, he says.

Even in Portugal, lauded as a decriminalization model, drug users face pressure to enter treatment, and there is strong social disapproval of drugs in the socially conservative, largely Catholic country. But that is not the case in freewheeling American port cities like San Francisco, with its long acceptance of drug use.

“The idea of decriminalization arose in the era when drugs were far more forgiving, but that’s no longer the case,” says Mr. Quinones. Many users should be forced to get help, he says, even by putting them in jail—but only if we rethink jails to include treatment pods and 12-step programs. This is being tried in some states hit hard by the drug epidemic, particularly Kentucky.

Policing can also be aimed at harm reduction. Since 2004, the city of High Point, North Carolina, has targeted low-level drug dealers and users by offering them help with housing and employment. The catch: Anyone caught peddling again gets locked up. The vast majority of sellers and users accept help. Other police forces are focusing just on drug users who commit crimes.

Growing social and legal tolerance of drugs dismays people like Mike Vigil, who had a 31-year career in the DEA, including chief of international operations. He acknowledges that interdiction and law enforcement have not solved the problem. But he says that the U.S. has failed to develop a comprehensive strategy, including investing in down-and-out communities where drug use flourishes and trying to reduce future demand through massive, sustained education programs.

Such efforts, experts say, need to go far beyond having a cop occasionally turn up to lecture bored kids on the dangers of drugs and should be woven into the curriculum, including teaching the neuroscience behind addiction. Messages also must be tailored to social media.

“We aren’t going to be able to arrest our way out of this,” says Mr. Vigil. His frustration is widely shared. “The U.S. has never taken the demand side of things seriously,” says former Mexican President Felipe Calderón.

Law enforcement also needs to adapt, tapping intelligence and targeting money flows. Over the last three years, European police hackers infiltrated two encryption services popular among criminals, obtaining hundreds of millions of messages that triggered hundreds of arrests. Artificial intelligence and other technical advances can help. British police identified one trafficker by analyzing fingerprints visible in a photo he sent via an encrypted app of his hand holding a block of Stilton cheese.

But a great deal of work remains, particularly in seizing illegal drug money. A 2017 study by Europol, the European Union’s police agency, estimated that fewer than 10% of suspicious money transactions were being investigated and less than 1% of illegal drug money seized. Now governments are trying to get help from banks, with prosecutors telling the financial institutions where to look for suspicious money, says former Europol director Rob Wainwright.

On the U.S.-Mexico border, American law enforcement officers are working to stop not just drugs going north but also money and weapons going south to fund and arm cartels. “Placing as much focus southbound as we do northbound could help,” says Ray Provencio, acting director at the El Paso port of entry for U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

The U.S. can also shift interdiction strategies, focusing more on helping China to stop exports of precursor chemicals and Mexico to better police the Pacific ports where the chemicals enter. Targeting precursor chemicals is difficult, however, because some are legal and used in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries. Gangs also respond to the banning of certain chemicals by quickly coming up with new formulations that are not yet outlawed.

In some ways, U.S. drug policy needs to return to the era of Nixon, says Prof. Humphreys at Stanford. Although Nixon coined the phrase “war on drugs,” his administration’s strategy was roughly two-thirds prevention and treatment and one third enforcement. “Nixon was much more moderate than is remembered by drug historians,” he says.

Source: James Marson, Julie Wernau, & David Luhnow for The Wall Street Journal