As queens or captains, women deftly operated ships across the Red Sea and Mediterranean 2,000 years ago.

BY SARAH DURN

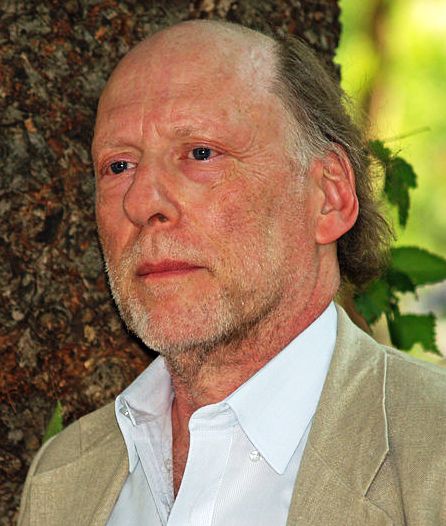

Archaeologist Carrie Atkins has found more than 20 references to female merchants scattered in millennia-old receipts, tax documents, and temple inscriptions. DEA/ICAS94/GETTY IMAGES

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

AROUND THE YEAR 200, TWO Roman women, Ailia Isidora and Ailia Olympias, walked through the impressive temple gates at Medamound, a temple complex outside of Luxor, Egypt. Their arms were heavy with an offering to the goddess Leto. They had just returned from a successful voyage across the Red Sea and were coming to thank their patroness. In the recorded dedication, we hear their voices echo back to us millennia later. They described themselves as “distinguished matrons, Red Sea ship owners and merchants.”

Ailia Isidora and Ailia Olympias weren’t the only female merchants in antiquity, says Carrie Atkins, an archaeology professor at the University of Toronto who has uncovered more than 20 references to female merchants in the early centuries of the Roman Republic. While some of these women were passive shipowners, others were heavily involved in the financing, managing, and perhaps even sailing of these merchant vessels. Even though Roman law dictated that a woman needed a male guardian’s approval to own property or basically do anything beyond the home, many of these female merchants acted without a man overseeing their every action. Atlas Obscura talked with Atkins about the little-known role of female merchants in the ancient world, a woman named Sarapias, and why her story and those of others like her have so often been overlooked

Were you surprised the first time you found evidence of female merchants?

I don’t really remember my reaction to it except thinking, “Wow!” I knew from other sources that women owned property. So when I started seeing that women owned ships, it wasn’t that surprising. But when I started digging into the actual tax receipts and [temple] inscriptions [like Ailia Isidora and Ailia Olympias’s] to see how involved they were, that’s what surprised me.

How involved were women in mercantile trade? Would they have sailed their own ships?

The agency of female merchants runs the gamut from passive owners of ships to those individuals who were actively participating in trade. We have individuals like Cleopatra I, the owner of at least one ship, and Cleopatra II, who owned at least six ships. Other individuals would be the captains and would arrange for cargo and take on those various middleman roles. Other individuals, like the two women [Ailia Isidora and Ailia Olympias] that put up this dedication, were really counting themselves as the merchants, as the ones who were engaging actively here in trade.

Were female merchants exceptional in antiquity?

I should say that I’m working here from probably 20 to 25 references. So when you think about all the evidence we have [that is, the hundreds of references to male merchants], this does seem rather exceptional. However, with that said, female merchants fit the models of references to males. So there’s nothing in these tax receipts, in these inscriptions, that really calls attention to the fact that they’re women.

For me, the takeaway here is the fact that female merchants could exist and weren’t singled out as something that’s special or remarkable means perhaps that’s the way it was looked on in antiquity. It wasn’t necessarily common, but it wasn’t something that was taboo or extra special to the degree that people go out of the way to comment on it.

Is there a female merchant that particularly grabbed your attention?

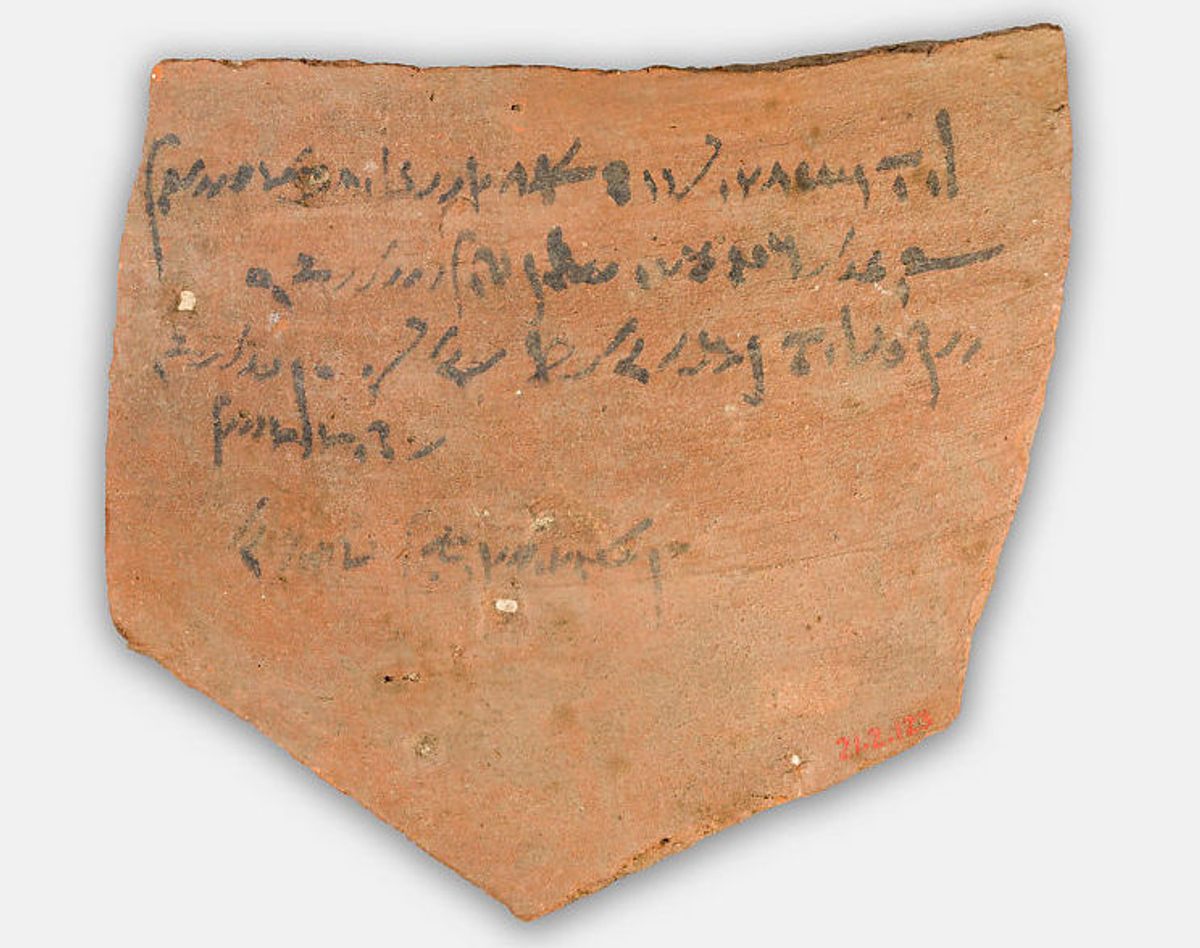

The one that I find really interesting is this reference to a woman by the name of Sarapias living in the second or third century. We have mention of her on a tax receipt, and it’s her first-person voice on the receipt as the one who’s arranging for this cargo of wheat aboard. Her brother was the captain or the helmsman of the ship. For many of these [references to female merchants], we don’t necessarily on the tax receipt have their voice. It’s somebody else who’s writing it. But for this, it’s her saying, “I was the one who arranged for this cargo of wheat.” Sometimes you’ll have a mention that so and so transcribed this or wrote this on behalf of the individual. Here I don’t think there’s any mention of somebody doing that. So likely she would have been the one writing this.

And so when I read that, that just completely engaged me, because this is a woman who’s speaking to us through the sources.

Why do you think female merchants in this period or more broadly in history are not well understood?

I think it is our perspective on history. Right now, we’re trying to look beyond male-dominant sources and look for individuals who are underrepresented in antiquity. I think this is one of those examples where really interrogating the sources allows us to have a different perspective that scholars may not have had in the past.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.