Colombia’s battle against Amazon deforestation: ‘The jungle is disappearing’

In a fiery speech at the UN General Assembly, Colombia’s first leftwing president did not mince his words about the destruction of the Amazon rainforest, 6 per cent of which lies within his country’s borders.

“Destroying the jungle, the Amazon, has become the slogan followed by states and businessmen,” said Gustavo Petro, who took office last month after campaigning on a platform of social and environmental justice.

In front of world leaders at the UN on Tuesday, he blamed the war on drugs and rich countries’ thirst for natural resources for the increasing rate of forest loss and called for a global fund to protect the Amazon, as well as debt-for-nature swaps that Bogotá could use to invest in environmental projects.

“The jungle is disappearing with all its life,” he said.

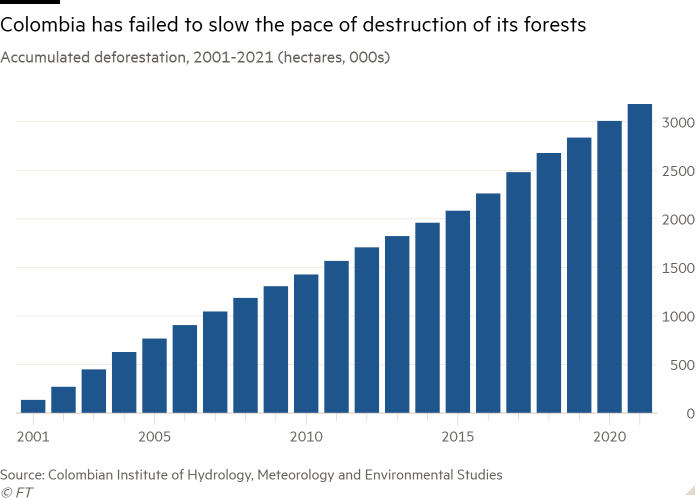

Colombia lost more than 174,000 hectares of woodland in 2021 — an area 30 times the size of Manhattan — with illegal clearances fuelling the surge. It was the country’s worst year for deforestation since 2018 and the second year in a row that the amount of land lost had increased, putting the country’s climate mitigation targets, indigenous communities and countless species of flora and fauna at risk.

Petro’s strategy to tackle deforestation would target land grabbers who cut down the forest to turn it into cattle ranching land that can be sold off, said Susana Muhamad, the country’s new environment minister.

“We will tackle the drivers of deforestation and not only those who are cutting down the trees,” said Muhamad, a prominent environmental activist. “It’s illegal land grabbing and that’s where we will apply a strategy determined by the armed forces.”

In the past two decades, Colombia has lost 3.1mn hectares of forest, 1.8mn of which are in the Amazon, a crucial absorber of carbon dioxide emissions and one of the world’s most biodiverse habitats. The first three-quarters of this year saw an increase of 11 per cent of forest loss in the Colombian Amazon compared with the same period last year, according to Ideam, the country’s environmental agency.

Muhamad said the government would prosecute those who fund land grabbing and would aim to improve the traceability of Colombian beef, 80 per cent of which is of uncertain origin. Other catalysts of deforestation include agriculture, logging, unauthorised construction, mining projects and coca production.

Up to 2014, large swaths of Colombia’s woodlands were in the hands of guerrillas and paramilitary groups and off-limits even to the most intrepid chainsaw-wielding loggers. But that changed when the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), the country’s largest guerrilla group, agreed to a ceasefire that paved the way for a 2016 peace deal.

“Once Farc lost de facto control of its territories, we saw deforestation increase quickly,” said Bram Ebus, author of a 2021 report on Colombian deforestation for the International Crisis Group. “Other non-state armed groups filled the void left by Farc. The state never showed up and wasn’t able to protect its own forests.”

Muhamad said that fully implementing the 2016 peace accord would pave the way for rural development programmes that boost eco-tourism and reforestation. “In the end, it will be more profitable to be with the rule of law than to be involved in illegal economies,” the minister said.

In 2019, Iván Duque’s conservative government launched Operation Artemisa, tasking the military with going after those responsible for deforestation. Last year, the government passed legislation making it easier to prosecute people for deforestation, with jail sentences of up to 15 years. Smallholder farmers, however, complain that the operation has targeted them unfairly.

Germany, Norway and the UK in 2019 offered Colombia combined financial incentives of up to $260mn if the country could show a sustained reduction in deforestation and emissions by 2025. But after the increase in destroyed woodland over the past couple of years, the country risks missing out on that money.

The state’s next goals are to reduce forest loss to 100,000 hectares a year by 2025 and to zero by 2030. But Margarita Flórez, head of Ambiente y Sociedad, a Colombian environmental NGO, said “it’s very unlikely” that the final target, which was agreed at last year’s COP26 climate summit, would be met.

“It takes just one day to destroy a hectare of rainforest with a chainsaw,” Carlos Correa, former environment minister under Duque, told the Financial Times just days after leaving office. “But it takes 25 years to restore it.”

Deforestation can have a devastating effect on indigenous and rural communities. Isaac Paez, who grows plantains on a small plot of land in Cartagena del Chiará, a deforestation hotspot in southern Colombia, said he and other people in his community who have opposed unregulated cattle ranching had received threats from armed groups.

“Ever since the 2016 peace agreement, deforestation has been on the rise here,” said Paez. “Unless we put a stop to large-scale cattle farming, it’s going to continue.”

Colombia was by far the most dangerous country in the world for land and environmental defenders in 2020, according to Global Witness, an international NGO. Of the 227 killings the organisation recorded worldwide, over a quarter were in Colombia.

Ole Reidar Bergum, a Norwegian diplomat who left Colombia last month after nearly five years as his embassy’s counsellor for climate and forests, said six people he knew personally were killed defending indigenous rights and the environment.

“You really think, ‘there’s no future here’, but then you stop and think about what these people were fighting for: their individual struggles,” he said. “And that’s when you think, ‘No! this fight has to go on’.”