INDIANAPOLIS (AP) — Cara Berg Raunick watched with bafflement as Indiana’s Republican legislators took less than two weeks to debate and pass an abortion ban that the governor signed quickly into law.

The women’s health nurse practitioner from Indianapolis was struck by just how frequently faith was cited in the arguments as reason to ban the medical practice. But Berg Raunick, who is Jewish, said those views go against her beliefs.

To her, a pregnant woman’s health and life is paramount, and she disagreed with legislators’ assertions that life begins at conception, calling that a “Christian definition.”

“That is a religious and values-based comment,” said Berg Raunick. “A fetus is potential life, and that is worthy of great respect and is not to be taken lightly, but it does not supersede the life and health of the mother, period.”

Arguments like this were central to an Indiana lawsuit filed in September against the state’s abortion ban, which is on hold amid multiple legal challenges. On Dec. 2, a judge ruled the ban violates the state’s religious freedom law, signed by then-Republican Gov. Mike Pence in 2015.

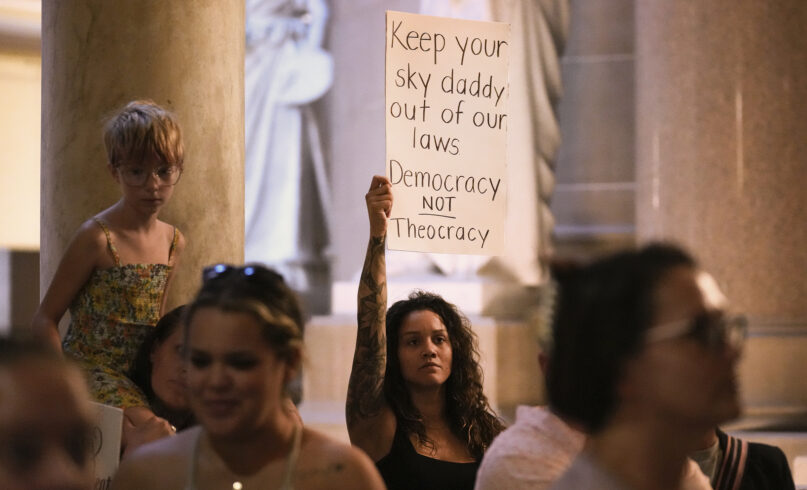

Critics of religious freedoms laws often argue they are used to discriminate against LGBTQ people and only protect a conservative Christian worldview. But following the U.S. Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade in June, religious abortion-rights supporters are using these laws to protect access to abortion and defend their beliefs.

The Dobbs v. Jackson ruling left abortion rights up to the states. As a result, lower courts in at least five states, including Indiana, have issued rulings in abortion-related religious freedom lawsuits.

There is a “huge diversity of the kinds of claims being made” in these cases, said Elizabeth Reiner Platt, who studies religion and abortion rights as director of Columbia University’s Law, Rights and Religion Project. The religious freedom complaints are among 34 post-Roe lawsuits filed against 19 states’ abortion bans, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

For some, abortion access can be a way to exercise one’s religion, Platt said. Other lawsuits challenge the bans under constitutional clauses that say the government is “establishing” a religion, imposing a law on residents who do not share that belief.

In the Indiana case, lawyers for five anonymous women — who are Jewish, Muslim and spiritual — and advocacy group Hoosier Jews for Choice have argued the state’s ban infringes on their beliefs. Their lawsuit specifically highlights the Jewish teaching that a fetus becomes a living person at birth and that Jewish law prioritizes the mother’s life and health.

The Indiana attorney general’s office this month appealed a ruling siding with the women and asked the state Supreme Court to consider the case. In January, the Indiana justices are already scheduled to hear another abortion ban challenge on the grounds it violates the state constitution’s individual rights protections.

Meanwhile, in Kentucky, three Jewish women are arguing the state’s ban violates their religious rights under the state’s constitution and religious freedom law. They say in a lawsuit, which has been removed to federal court, that Kentucky’s Republican-dominated legislature “imposed sectarian theology” by prohibiting nearly all abortions. The ban remains in effect while the Kentucky Supreme Court considers a separate case challenging the law.

For those wanting to end abortion bans, lawsuits arguing state governments are establishing a religion via the bans could be more effective than ones arguing for the free exercise of religion, said Elizabeth Sepper, a University of Texas at Austin law professor. The former would apply to more people, she said.

“If an abortion ban violates either a state establishment clause or the federal establishment clause, then the entirety of the statute comes down,” Sepper said.

Some state lawsuits use both arguments, such as a case filed by Planned Parenthood that in July successfully blocked Utah’s ban. The law is on hold pending a decision from its state Supreme Court.

That same month, a lawsuit partly based on Wyoming’s religious-liberty clause blocked the state’s abortion ban. The Wyoming high court said Dec. 21 it would not weigh in on the state’s new abortion ban for now.

Elsewhere, Florida religious leaders in June cited the state’s religious rights law and state constitution’s privacy protections in multiple lawsuits against their state’s 15-week abortion ban. A request to hear an appeal of the ban, which remains in effect, rests before the Florida Supreme Court.

Amid the legal machinations, abortion access remains a divisive issue among the nation’s faithful. In June, clergy across the U.S. reflected that divide and its nuances as they rearranged worship plans to provide religious context — and competing messages — after Roe was overturned.

Across the U.S., few voters in religious groups say abortion should always be illegal, according to AP VoteCast, a sweeping survey of the midterm electorate. But religious groups differ in their level of support for abortion.

While Protestants in general are closely divided over whether abortion should generally be legal, most white evangelical Protestants — about 7 in 10 — say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. Similarly, about 7 in 10 Mormon voters say abortion should be generally be illegal.

By comparison, 6 in 10 Catholic voters, about 8 in 10 Jewish voters and close to 9 in 10 religious unaffiliated voters say abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

An array of religious beliefs were on display during Indiana’s summer legislative debate, which ultimately resulted in the state becoming the first in the U.S. to enact tighter abortion restrictions after Dobbs. The state law displeased both abortion-rights advocates, who say it goes too far, and anti-abortion activists, who said it didn’t go far enough.

State Rep. Ann Vermilion, who opposed the ban, condemned her fellow Republicans that called women “murderers” for getting an abortion.

“The Lord’s promise is for grace and kindness,” Vermilion said. “He would not be jumping to condemn these women.”

Dr. Kay Eigenbrod, an Indianapolis obstetrician-gynecologist who attended Indiana Right to Life’s “Love them Both” rally during the debate, said in a July interview that, because of her Catholic upbringing, she supports a complete abortion ban without exceptions.

“Women just don’t have to turn to abortion for any reason,” she said. “We as a society just need to be better about supporting them both.”

Months later, Berg Raunick, a member of Hoosier Jews for Choice but not involved in the lawsuit, hopes lawmakers will continue to value religious freedom.

“That has to mean protecting all religions, not just Christianity, and not just the majority,” she said. “Now, we sort of wait and see how how true that is.”

___

AP writer Hannah Fingerhut contributed to this report from Washington, D.C. Arleigh Rodgers is a corps member for the Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues. Follow her on Twitter at https://twitter.com/arleighrodgers

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)