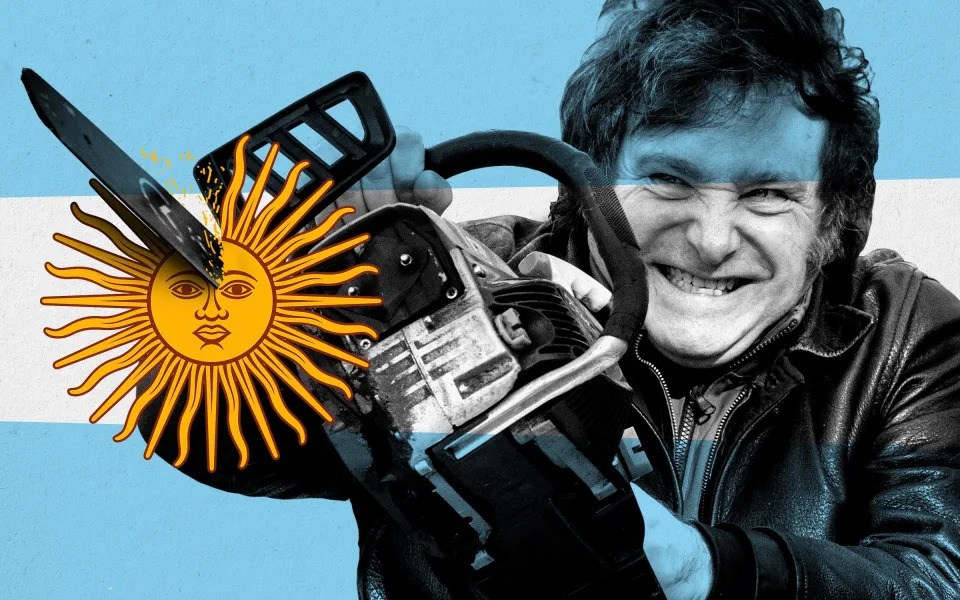

Javier Milei’s extreme experiment in Austrian economics is sailing dangerously close to the wind

Javier Milei has started his libertarian economic experiment to transform Argentina. In a series of dispatches, The Telegraph’s International Economy Editor Ambrose Evans-Pritchard travels through what used to be one of the world’s richest nations to examine whether “shock therapy” can work.

The world’s first and only libertarian experiment in Austrian economics has confounded its critics in one respect. Five months into the most violent fiscal shock ever attempted in a modern developed economy, President Javier Milei remains astoundingly popular.

His poll ratings have hardly moved since he won a landslide victory last November, vowing to take a chainsaw to the deformed Argentine state and chase the eternal Peronist casta from public life. A general strike has been and gone. Nothing seems to hurt him.

“Most analysts in December didn’t think this government would last three months,” said Martin Castellano, Latin America chief at the Institute of International Finance.

Milei has bet everything on crushing inflation by means of a budget surplus, asking the nation to endure a short but violent economic shock in return for sunlit uplands.

“It had to be a tremendously abrupt adjustment. There was no alternative. Weekly wholesale price inflation was running at 17,000pc in December and we were going into hyperinflation,” said the president.

“We had the worst inheritance in Argentina’s history. When a country has a budget deficit of 4pc of GDP, that is a yellow warning. When it’s 8pc, that is a red warning. Ours was 17pc, once you throw in the central bank deficit,” he said.

He can claim a win. The monthly rate is expected to drop below 5pc in May, far sooner than most thought possible. Listed prices are appearing again in groceries. Bread, rice, fruit and vegetables are falling. The food and drinks basket has been flirting with deflation.

His second win is to reach a fiscal surplus, or at least the statistical illusion of a surplus. “This is the only basis to end the hell of inflation once and for all. If the state stops spending more than it brings in, and stops printing, there is no inflation,” he said.

Scratch deeper and the Austrian story starts to unravel. The rhetoric is a blend of Hayek’s Road to Serfdom and Friedman’s Money Mischief but the policies so far are a Latin American stew of state meddling. Plans to abolish the central bank and dollarise the economy have been shelved.

“Milei is doing the opposite of what he said would do. He sold everybody liberalism but he is actually pursuing highly-interventionist policies,” said professor Roberto Cachanovsky, author of the Argentine Syndrome.

Inflation has been repressed by controls and a badly overvalued exchange rate – or, to be precise, thirteen different exchange rates. Buenos Aires is now more expensive than Tokyo. That is not an export-led growth strategy. It is not how tiger economies take off.

Whatever the original intention, the Milei experiment is following a very different course from the German plan of Ludwig Erhard in 1948, which eliminated Nazi and Allied price controls and created a credible Deutsche Mark almost overnight.

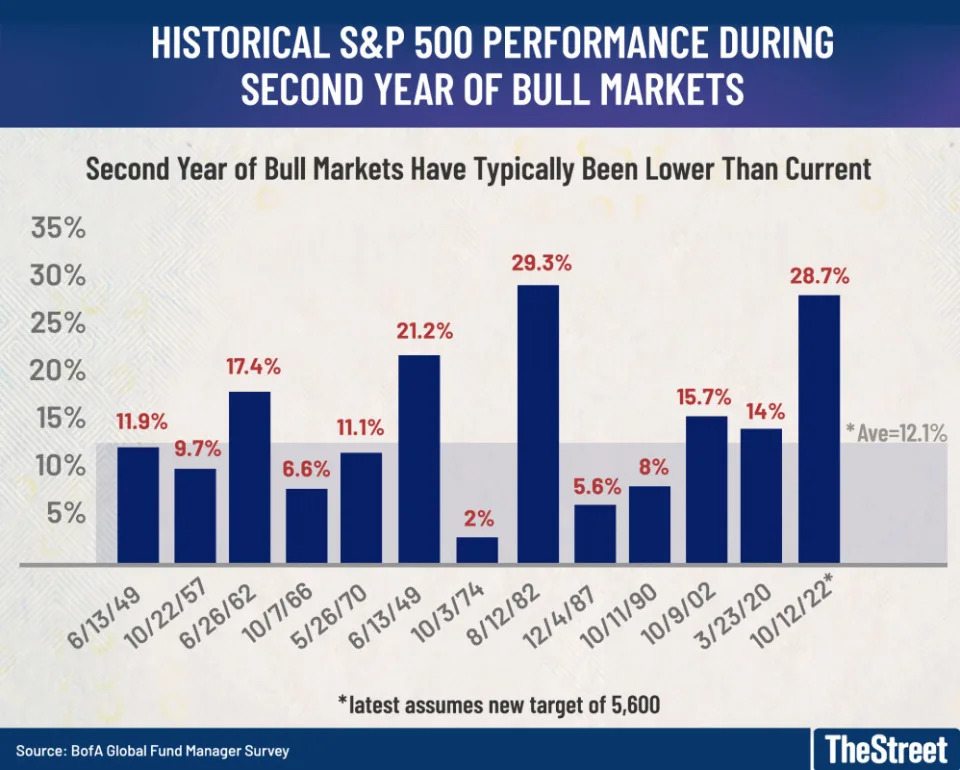

The ‘Argentina trade’ has been a windfall for hedge funds since November. Stanley Druckenmiller, founder of Duquesne Capital, said he took the plunge after hearing Milei’s paeans to raw capitalism in Davos.

“I called up and said ‘give me the five most liquid ADRs [American depository receipt] in Argentina’. I followed the old Soros rule, invest and then investigate. So far it’s been great,” he told CNBC’s Squawk Box.

Portfolio Personal Inversiones says the Merval equity index is up 80pc in dollar terms and the average return on Argentine bonds has been 70pc. Goldman Sachs and UBS warn that the snap-back rally is largely over, code for ‘take your profits and get out’.

“Global investors have given Milei the benefit of the doubt that Argentina may not have to default after all. They were pricing in a 30pc return on debt restructuring and now it is around 48-50pc,” said Claudia Calich, head of emerging markets debt at M&G.

“What he has done on a cash accounting basis is remarkable, so hats off to him. But that alone is not enough to bring boom times. We haven’t seen the recovery in foreign direct investment,” she said.

Indeed not. The Argentine economy is close to cardiac arrest. The industrial collapse in March was hair-raising: cars -24pc, metals and machinery -37pc, furniture -40pc, steel -42pc, and tarmac -69pc.

“Never since they started measuring the data has there ever been such a fall across the board, not even during the pandemic,” said research group Fundar.

This is what happens when you cut off funding for 2,000 public infrastructure projects, cut fiscal transfers to the regions by 98pc, stop paying state debts owed to private contractors, and cut pensions in real terms by two fifths.

“Public works are practically paralysed. We expect 100,000 people to be laid off, and each one of them hits a whole universe of other people,” said Gustavo Weiss, head of the Chamber of Construction.

The recession itself is now shrinking the tax base, causing a 13pc fall in real tax revenues in April. In a fit of libertarian rapture the president chose this moment to urge business leaders to evade taxes if they could get away with it.

“The dodgers are heroes who know how to escape the claws of the state. If you buy dollars on the black market, even better, because then you don’t have to pay a lot of stupid fees,” he said.

Unless the economy hits bottom soon and Argentina starts to feel the rocket thrust of Milei’s V-shaped recovery – so far looking like a stretched U at best – this fiscal overkill could start to become self-defeating, setting off a vicious circle of rising deficits requiring yet further cuts akin to the waterboarding of Greece a decade ago.

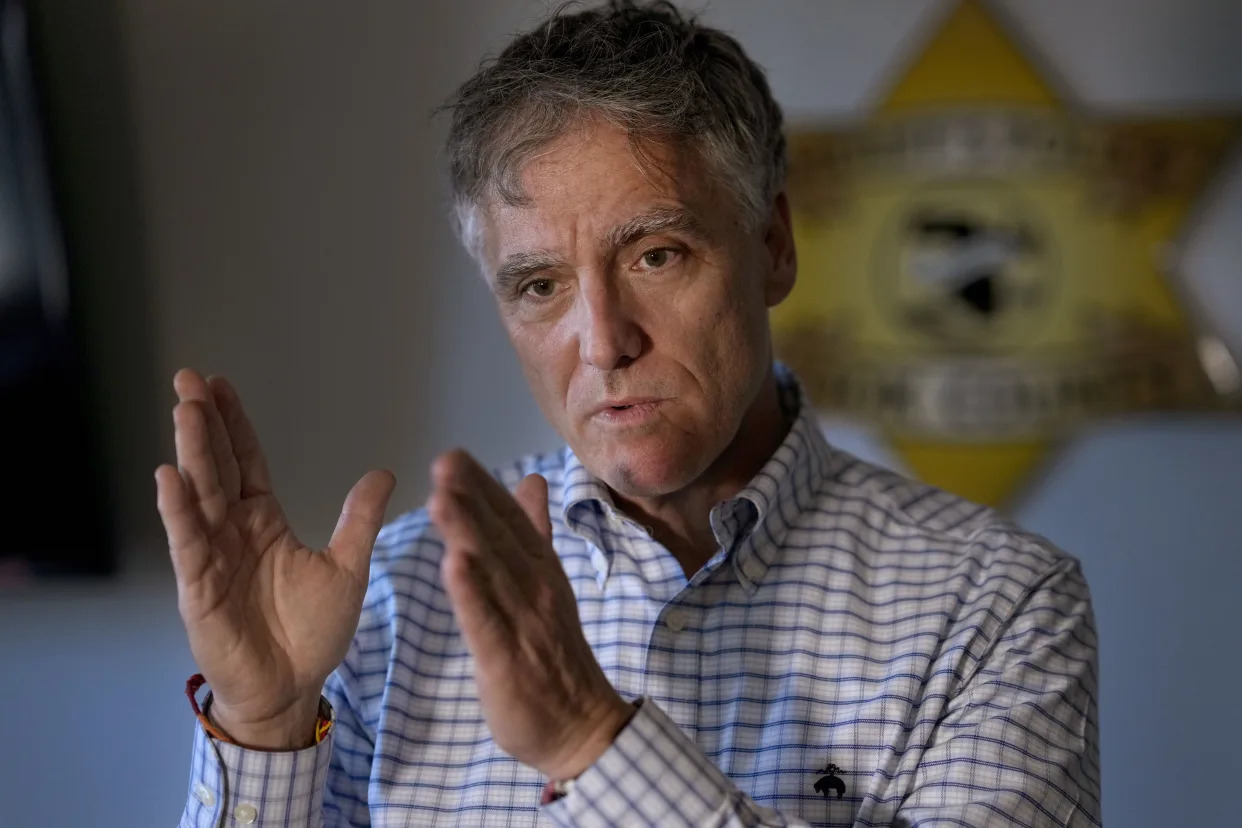

“We’re heading into an economic depression,” said Carlos Rodriguez, a Chicago school monetarist and ex-rector of the Centre of Argentine Macroeconomic Studies.

“There is no economic strategy. The austerity plan is simply not to pay any money to anybody. There has been a brutal reduction in state spending that doesn’t seem to follow any logic. At some point the roads and the trains are going to fail,” he said.

“Milei came out like a rockstar and the people believed him. But his remedies are as old as the hills. If the plan is just to freeze public spending in nominal terms, Milei is going to become the most hated man in the country,” he told La Nacion.

The second danger for Milei is that the exchange rate will blow up in his face. The peso is effectively fixed. A crawling peg slides by at 2pc a month but internal prices have doubled in the meantime.

“All the benefits of the devaluation in December have been eaten away by inflation. Currency overvaluation has always ended in tears in Argentina and I’m not convinced that this is going to be any different,” said Todd Martinez, head of sovereign ratings for Latin America at Fitch.

It is the lesson of the Asian crisis in 1998, and the UK’s ERM crisis in 1992. It is the lesson of Argentina’s own crisis in 2000-2001, which ended in the spectacle of president Fernando de la Rua being lifted from the roof of the Casa Rosada by helicopter as an insurrection gathered below.

“If the government has got any sense it will do what the International Monetary Fund and every economist in Argentina is telling them to do, and start to devalue a little more each day,” said Domingo Cavallo, the economic tsar of the 1990s and survivor of the de la Rua disaster.

“If they fall in love with an overvalued exchange rate, they are going to endanger the competitiveness of every sector of the Argentine economy,” he said.

One can understand why Milei has chosen to buck the market and rig the country’s most important price signal. He inherited a central bank with negative foreign exchange reserves, and a sobering calendar of debt payments, including tranches owed to the IMF and a $4.9bn (£3.9bn) swap loan from China that expires in June. It was deemed too dangerous to open the capital account.

He is now caught in a trap. The peso has decoupled so far from economic fundamentals that markets are already anticipating another large devaluation. Grain farmers are withholding much of the harvest until they receive a better dollar rate. It is a supply strike. Ludwig Erhard would have seen the threat immediately.

“People are voting with their feet. There is an invasion of Argentines in Chile and Brazil buying clothes and shoes because it’s much cheaper there,” said Hector Torres, a former IMF executive director.

“Argentines think in dollars. Nobody is going to believe anything the central bank says until it has been building substantial foreign reserves for at least three or four years,” he said.

The reserves have been rising – chiefly due to the ferocious economic downturn – but are still barely above net zero and may already be levelling out. The longer that Milei holds onto his exchange rate anchor, the worse the next devaluation will have to be, leading to another spike in inflation that will puncture his authority.

Milei’s team have been pleading with the IMF for a new package of $15bn but the Fund has had its fingers burned too many times. Argentina is already the institution’s largest borrower with $32bn of outstanding debt.

“I can say with certainty that my old colleagues at the IMF are not going to lend us $15bn to defend an overvalued exchange rate. It is likely to be a third of that at best. And they don’t want to be blamed for Milei’s shock therapy either. They want quality cuts, not indiscriminate liquidation,” said Torres.

Javier Milei’s free market revolution will remain a pious wish until he learns how to coexist with a hostile congress and with governors from opposing parties in every state. He has been able to cut through some red tape by decree power. The rental market has been opened up.

But decree power cannot be for radical change without provoking a dangerous backlash. Salvador Allende tried pushing through his neo-Marxist revolution in Chile by circumventing parliament, and it ended very badly.

Milei has yet to pass any legislation. He has sent an omnibus law to congress – dedicated “to the delinquents who tell you the state is efficient” – that would in theory give him the legal powers to slash the Argentine state to its 19th Century pre-welfare functions.

“I have 1,000 reforms coming, and after that another 3,000, and if they are passed, Argentina is going to climb 90 points up the global competition league,” he said.

“It is not good enough for me to match Germany. I want us to be like Ireland, that went from being the most miserable country in Europe to a per capita income 50pc higher than the EU average.” he said.

One wants to whisper in his ear that Ireland invested strategically in public education as far back as the 1980s. The Celtic Tiger is a vindication of the policies that he has repudiated in his own country.

Milei has disfunded anything deemed woke. The equalities institute (INADA) and the art and films body (INCAA) have been gutted. The schools, universities, and hospitals are on iron rations.

“You feel like everything is collapsing like a house of cards,” said Marcel Melo, head of the hospital at the University of Buenos Aires.

“We’ve cut surgery by 70pc and we’re down to dealing only with emergencies because we can’t buy basic supplies.”

Previous waves of liberal reform in Argentina – Alfonsin, Menem, Macri – were aimed at shutting down wasteful pockets of the state. The goal was efficiency. They were, if you like, Thacherite.

Milei’s declared war of annihilation against the public sector is of a different character. Nobody knows what is theatre and what is real, or how far he really intends to go.

The practical limit is that Milei lacks the votes to pass his laws, and his game of political chicken against congress can only take him so far.

He is learning in the school of hard knocks that you have to do deals. He has already acquiesced as 60 articles of his labour reform are reduced to 16, with another four more are likely to go in the senate.

My guess is that Milei will in the end adapt to the tactics of his professed idol, Margaret Thatcher, who knew when to fight, and when to yield, and had a healthy respect for the uses of the state. But he will do so only after wasting much of his political capital.

The Argentine economy defies normal economic analysis. It has a thriving underground sector. People stash dollars hidden in the proverbial mattress. The country has bounced time and again from circumstances that would seem to be hopeless through a European or American lens.

The commodity supercycle will lift the Argentine economy off the reefs as it has done through so many cycles before, this time turbo-charged by the shale reserves of Vaca Muerta and the Lithium Triangle in the high Andes.

Once the US Federal Reserve cuts interest rates, a fresh global credit cycle will set off a wave of investment into emerging markets as it always does. Some of this excess global capital will make its way to Argentina, so long as rational policies prevail.

Will anything be left of Milei’s experiment in Austrian economics? Perhaps something, if he plays his cards cleverly. But you don’t change the anthropological DNA of a nation by tilting at windmills.