MAIB Cites Mechanical Failures, Modifications, and Crew Response to Fire

The UK’s Marine Accident Investigation Branch issued a report on a 2021 fire aboard a RoRo cargo ship as it was departing the Port of Hull, England. It found a broad series of mechanical failures, improper parts used in non-standard modifications, and a failure by the crew to “follow accepted procedures,” which contributed to the significant damage to the vessel’s auxiliary engine room. However, there was no loss of life, and the vessel was recovered and moved back to the dock despite these issues.

The cargo RoRo Finnmaster (8,800 dwt) was built in 1998 and operated on a regular route between Hull and Helsinki, Finland, for Finnlines, carrying RoRo and containerized cargo. The ship had a crew of 16 aboard and was making its normal departure from Hull when, eight minutes after leaving the dock on September 19, 2021, smoke alarms sounded and a fire was discovered in the auxiliary engine room. The ship was still within the confines of the harbor and, within four minutes, lost all main electrical power and propulsion, leaving it drifting while the crew struggled to put out the fire.

Eleven minutes after the Finnmaster had left the dock, the first of two tugs was alongside, followed by a second one in an additional 11 minutes. They had the ship back alongside a dock approximately 50 minutes after it had cast off. The crew had finally been able to extinguish the fire through a combination of the CO2 system and entering the space with dry powder extinguishers.

(MAIB report)

MAIB found in its investigation that the fire started when one of the auxiliary engines malfunctioned, causing hot exhaust gas to impinge on a flexible hose, which then failed and leaked fuel under pressure onto a hot component. They concluded that the hose had been installed in the fuel system during a modification that “did not meet the required standard” and that it was fitted “in an inappropriate position.” The class society, RINA, had not had oversight or approval for the modification.

Once the fire started, other mechanical failures resulted as they sought to respond to the growing emergency. The emergency generator’s circuit breaker malfunctioned, so it could not be connected to the power supply. The CO2 fire-extinguishing system failed to fully operate due to a defective flexible hose assembly and leaks in the pilot system. The ultrahigh-frequency handheld radio system being used by the engineers failed, cutting off communication to the master on the bridge.

The 167-page report also highlights actions by the crew who attempted to enter the auxiliary engine room with dry powder extinguishers but were forced out by the heat. Some crew remained at their operational stations, and some went to emergency muster stations. The electrician attempted to restore power, but the crew was working with flashlights. Some of them attempted to re-enter the auxiliary engine room when they discovered not all the CO2 bottles had activated. They reported remnants of a small fire and, wearing compressed air breathing apparatus, re-entered and extinguished the fire with a dry powder extinguisher. The report says the crew’s response, affected by the loss of critical safety systems, was “ineffective.”

MAIB made a total of 12 recommendations, split between the Finnish administration as the ship’s flag state, the owners Finnlines, and RINA, the responsible class society. They called for IMO amendments and guidance on the testing of emergency power and radio systems, as well as fire-extinguishing systems. To the shipping company, they recommended revised and updated training, response, and defect reporting procedures. They recommended that RINA make a recommendation to the International Association of Classification Societies for an urgent review into the procedural requirements for service supplies conducting maintenance of fire protection systems, and the guidance on support provided to chief engineers.

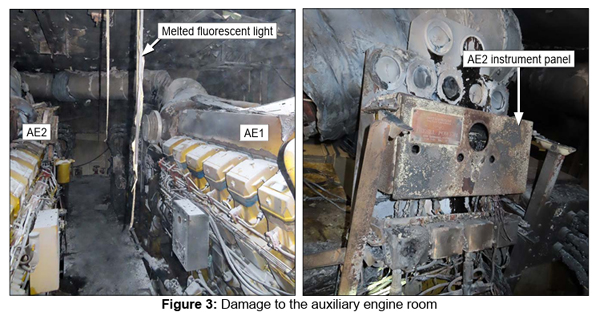

The vessel sustained significant damage to equipment in the auxiliary engine room. The heat from the fire melted plastic components and damaged wiring. Smoke damage, however, was limited largely to the compartment. The ship was repaired but from to Grimaldi the following year. It continues in service managed since 2024 by Balearia.

Iranian crude exports to China from Kpler and Vortexa estimates (CJRC)

Iranian crude exports to China from Kpler and Vortexa estimates (CJRC)