This Was Always Coming – OpEd

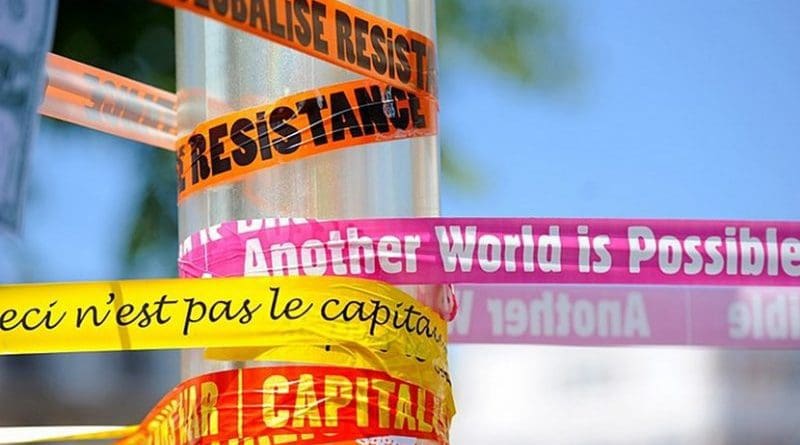

Anti-capitalism and anti-globalization banners. Photo by Guillaume Paumier, Wikimedia Commons.

For decades — or perhaps centuries — collapse has been underway: the fragmentation of social, economic, and political order; the hollowing-out of law at both domestic and international levels; and the unrelenting duplicity and hypocrisy of those in power pushing the boundaries.

Today, chaos reigns: widespread violent extremism, state impunity, acute social divisions, and appalling environmental degradation. It was always going to come to this. Death and destruction are inbuilt.

Structural injustices and destructive behaviours are pushing planetary and socio-economic systems beyond their carrying capacities, toward critical tipping points and potential collapse.

The destruction of civilisation’s architecture, visible all around us, is the inevitable outcome of the poisonous ideology that underpins our age — colonial neoliberalism, coupled with State complacency.

Neoliberalism is inherently divisive and unjust, and therefore incapable of producing peace or social justice. Entwined with imperialism, it functions as the ideological instrument of global domination, suppression, and control.

Emerging in the late 20th century under Thatcher and Reagan, neoliberalism was exported globally through institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, and World Trade Organisation (WTO). Social protections and workers’ rights were dismantled, public industries privatised, and industry deregulated.

Through debt, trade agreements administered via the WTO, and Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), nations in Sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia were subordinated economically and politically to the Global North — extending colonial control through economic and political mechanisms.

At its ideological core, neoliberalism rests on a nihilistic doctrine: that materialism, profit, and individual desire are key human values. Within this reductive worldview, production is organised solely around what is profitable for capital — exploiting labour, resources, and productive assets, enriching imperial and colonial centres rather than meeting human needs or safeguarding the planet.

It is an inhumane, violent system, administered by colonial powers dominated by the US, to the detriment of the poor everywhere and of the natural world.

Colonial neoliberalism builds upon centuries of domination of the Global South by the North. From the 1500s onwards, European powers plundered Africa, Asia, and the Americas, extracting resources and subjugating populations into forced labour for their enrichment.

After the Second World War, the United States took up the reins of exploitation, using economic and military power to assert its will. Hundreds of thousands were killed in suppressive acts of unrelenting violence in Korea, Vietnam, the Congo, and Chile. Through direct actions, coups, and covert operations, economic control and political suppression were used by US administrations of both colours to subjugate these nations.

Today, the same inhumane playbook is being applied in Palestine, where Israel — a Euro-American settler colony and imperial outpost in the Middle East — is, as the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry recently confirmed, carrying out genocide against Palestinians in Gaza, alongside the systematic destruction of Palestinian society and the environment. Hamza Hamouchene describes this as a Holocide: “the total destruction of the social and ecological life in Palestine,” capturing the entwined human and environmental devastation wrought by imperial-colonial systems, in full view, and to the shame of all.

Economic democracy

Whilst Western democracies may allow a degree of political participation, there is no economic democracy. Neoliberalism concentrates economic power in the hands of a tiny few — a number that shrinks year on year, even as their wealth expands. Ordinary people — the 99.9% — have no meaningful control over the economic systems that govern their lives.

The central force driving economic policy and corporate life is the pursuit of profitable returns for capital — a goal almost always prioritised over social needs such as healthcare, education, and affordable housing.

The consequences of this doctrine are manifold: vast inequalities of wealth, income, and opportunity; austerity and crushing debt; weak, dependent governments at the mercy of markets and multinational corporations; inadequate public services; and ongoing environmental destruction, compounded by governmental inaction.

Alongside these structural injustices, the Ideology of Greed and Division promotes a self-perpetuating series of destructive values: selfishness, conformity, and relentless competition are elevated, while cooperation and compassion are marginalised. It fuels divisions of all kinds, and division begets conflict, within individuals, communities, nations, and globally.

The extreme fractures now visible across society — economic, social, political, legal, and ecological — are tearing at the very fabric of life.

This total chaos was always going to happen. This divisive, unjust, and unhealthy way of living, founded on a violent ideology rooted in exploitation, greed, and division, could only lead to this point — and beyond. We may not yet have reached the limit of destruction: a colossal crisis of interrelated failures.

Nowhere is the system’s barbarism clearer than in Palestine, where Israel’s genocide lays bare the vicious logic of empire: impunity for the powerful, the abandonment of international law, unrestrained violence, and the subjugation of truth.

It is a system violent without limits, driven by men obsessed with power and control, that enables figures like Netanyahu — and others, including Trump — to seize power and commit unimaginable crimes.

Graham Peebles

Graham Peebles is an independent writer and charity worker. He set up The Create Trust in 2005 and has run education projects in India, Sri Lanka and Ethiopia where he lived for two years working with acutely disadvantaged children and conducting teacher training programmes. Website: https://grahampeebles.org/