The Politics of Pushing the US to Become a “Christian Nation”

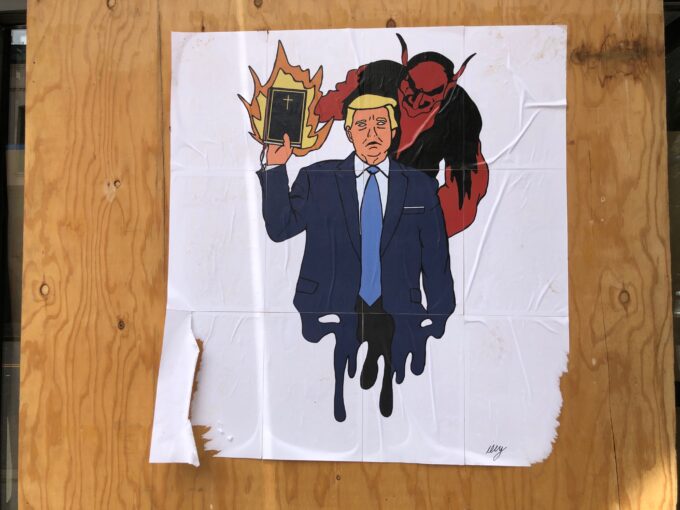

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

Last month, a small brick was removed from our Constitutional wall that separates the state and church. The New York Times’s investigative reporters reported in July 2025 that the Internal Revenue Service carved out an exemption from what is referred to as Congress’s 1954 Johnson Amendment in nonprofit law, which bans nonprofits from endorsing candidates.

The IRS joined plaintiffs in asking a federal judge to block this and all future administrations from enforcing the ban, specifically that churches endorse candidates from the pulpit. This exemption did not extend to other non-profit organizations.

The IRS decision responds to efforts, like those of the right-wing Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF) over the past fifteen years, to challenge the constitutionality of this law in court based on the constitutional right to free speech. They proclaim that they are “protecting their God-given right to speak freely and live out their faith, threatened by radical activists in government, education, and the wider culture who would subvert the God-designed role for families.”

Current House Speaker, Rep. Mike Johnson, a former senior legal counsel with the ADF, said in 2008, “I think we would defend that as a constitutional right to free speech” in advocating that pastors be able to endorse candidates from their pulpits. However, Diane Yentel, president of the National Council of Nonprofits, representing 30,000 of them, believed that this IRS ruling was “not about religion or free speech, but about radically altering campaign finance laws.” Yentel warned that allowing tax-exempt groups to endorse candidates could lead to “opening the floodgates for political operatives to funnel money to their preferred candidates.” Meanwhile, they can receive generous tax breaks by contributing to churches whose views may be shared by only a portion of the voters.

Lloyd Hitoshi Mayer, a law professor at the University of Notre Dame, has studied how churches are regulated in their political activities. He believes that the IRS’s decision will encourage future politicians to promote religious objectives because, “It also says to all candidates and parties, ‘Hey, time to recruit some churches.’”

IRS’s court action weakens the principle of “separation of church and state,” which is attributed to Thomas Jefferson by many, including Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black. He wrote in Everson v. Board of Education (1947) that, “In the words of Thomas Jefferson, the clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect a wall of separation between church and state.”

America’s history is marked by ongoing tension between spiritual and secular forces that shape how a democratic republic should function to serve the needs and protect the freedoms of all citizens. This tension stems from the principles embodied in our Constitution.

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution includes two clauses that must be balanced. The Establishment Clause states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,” and its second clause is the Free Exercise Clause, which says that “Congress shall make no law … prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”The second clause is used by conservative religious leaders and many Republicans to advocate for allowing religions to play a significant role in passing laws that are promoted as protecting families and fostering a healthy spiritual environment.

These laws promote their beliefs while ignoring those of other citizens who do not share them. Consequently, some citizens could be punished for breaking what essentially is a religious law, not a secular law meant to protect everyone’s freedoms.There are many instances of laws being passed. One of the less burdensome ones was the Blue Laws, which banned the sale of alcohol on Sundays. However, there are others that are simply unenforceable because most citizens do not agree with them.

Passing the Eighteenth Amendment and Congress enacting the Volstead Act, which imposed Prohibition on all citizens, is a prime example of religious fervor demanding adherence to a noble virtue. Due to organized efforts by the religiously driven Anti-Saloon League and allied Protestant and Catholic churches, Congress overwhelmingly ratified the Eighteenth Amendment with a 68 percent supermajority in the House of Representatives and 76 percent support in the Senate. Toward the end of the 13-year Prohibition, with the passage of the new 21st Constitutional Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment, there was widespread public alcohol consumption. Although public safety was the utmost objective of the Prohibition, more deaths occurred during it than before it began or after it ended.

One hundred years later, another major religious-led effort is underway to ban abortions. This law is unlikely to be widely enforced unless law enforcement increases its arrests. In the case of prohibiting abortions, the public opposes this move even more than banning public alcohol consumption. In both scenarios, religious beliefs and political opinions have been and continue to be protected as free expression from pulpits. However, endorsing candidates for public office from the pulpit might be seen as a form of religious instruction, which blurs the boundary between church and state.

Demarcating the authority of the church from the state has been a long-standing issue, dating back to the country’s founding. Only four of the original 13 colonies were established on the principle of complete religious freedom, with no official state church. Although this process was gradual, religious tolerance allowed the practice of various Christian denominations and some Jewish communities. However, public funds were used to support churches in most of the colonies.

Following European tradition, some of the early state constitutions required officeholders or voters to take an oath affirming their adherence to the major principles of the established church in their state. This practice was rejected when the founders wrote Article 6 of the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits taking such oaths to secure a national office.

While the Constitution clearly states that no religious practice can be mandated as a law applicable to everyone, there have been accommodations made to officially recognize certain religious practices and to tolerate religious expression in public spaces. Some of the earliest examples include adopting Christmas as a federal holiday since 1870 and the use of the Bible for presidents to take their oath of office, with only two not doing so.

This approach is known as accommodationism, which claims that the First Amendment can promote a beneficial relationship between religion and government. What some considered to go beyond mere accommodation was when Congress made significant changes in the 1950s.

A reference to God was introduced into the Pledge of Allegiance: “… the Republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” The national motto E pluribus unum (“Out of many, one”), which appeared on the dollar bill and our Great Seal of the United States, was replaced with “In God We Trust.” This change was challenged in court as a violation of the Constitution, but the Supreme Court ruled that it would be considered ceremonial deism , not religious in nature.

These changes stemmed from the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS)’s 6 to 3 decision in Zorach v. Clauson (1952), which supported accommodationism by stating that the nation’s “institutions presuppose a Supreme Being” and that government recognition of God does not amount to establishing a state church, which the Constitution forbids. As a result, SCOTUS has leaned toward adopting a key principle of accommodationism, interpreting the First Amendment as allowing government actions that promote religion, but not religious institutions.

One of the three dissenting Justices was Hugo Black, who is considered one of the strongest advocates for interpreting the Constitution through the conservative legal theories of textualism and originalism. In this instance, these theories were used to oppose the “liberal” theory of accommodationism, which would allow the government to be “friendly” with religion.

The question is, does accommodationism allow some religions, especially those with the most voters, to fund candidates who promote their religious beliefs? If so, doesn’t that make a church congregation act like a political party? Where is the wall that separates church and state?

This situation should lead citizens to question whether President Trump’s statements, along with those of his cabinet secretaries and Republican Congressional members, reflect the beliefs of a particular religion or if they represent those of a secular democratic government. The first restricts citizenship; the second broadens it to include everyone.

Often, Trump-appointed public officials refer to the Christian God, not just any deity. Are they promoting Christian beliefs or democratic principles? Are they redefining democracy’s freedoms as existing within a Christian society? If so, what happens to those who are not Christians in that society? Or to Christians who do not practice their faith? Here are two examples from public officials in the Trump administration to consider when answering those questions.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth reposted a CNN video on X that examined the beliefs of Doug Wilson, cofounder of the Communion of Reformed Evangelical Churches (CREC). CREC promotes his views, as stated in the CNN report: “I’d like to see the nation be a Christian nation, and I’d like to see the world be a Christian world.” The Pentagon chief spokesman said Hegseth is “a proud member of a church” affiliated with CREC, and he “very much appreciates many of Mr. Wilson’s writings and teachings.”

But does Hegseth cross the line from simply promoting belief in a single deity to acting as an acolyte of the Christian God? For instance, he uses taxpayers’ money to hold Christian prayer services inside a government building during working hours. If you want to get promoted by Hegseth, don’t you think you’d show up and be seen as a good Christian?

Meanwhile, Secretary Kristi Noem is framing her Department of Homeland Security’s actions as following the directives of the Bible. Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons from Interfaith Alliance points out DHS videos that boast of their mass deportation efforts using Bible verses. “As images of helicopters and tactical agents ominously scroll, the narrator says: ‘Then I heard the voice of the Lord saying, ‘Whom shall I send? And who will go for us?’ And I said, ‘Here am I; send me.'”

Does using text from the Bible suggest that the government is acting on God’s will? Isn’t this a religious belief? How does this align with a secular democratic government that isn’t dependent on approval from any church or religious book? These statements and actions from the Trump Administration should raise concerns among all citizens, regardless of their religion.

Once a republican government adopts the language, symbols, and beliefs of a religion, it becomes easy to take the next step: claiming that its authority comes from God. This signals the end of democracy because then the nation’s leaders determine what God wants from all of us.

That is why the founders of our republic aimed to separate church and state—to prevent the rise of another divine king. If a leader or political party claims they are accountable to God, aren’t they really most accountable to those who had the power to place them in office?

Today, billionaires, with their vast wealth, hold the most power to influence who leads the republic. As they collaborate with large religious groups, it is evident that this alliance of mutual expediency advances public policies that primarily benefit their interests, rather than those of the general public. Citizens need to ask themselves with this alliance guiding our nation—how will it end?

Trump: Make America White Again

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

Donald Trump successfully championed anti-immigrant hysteria during his 2024 (re)election campaign … and it worked. Once in office, immigration became the leading political issue of Trump’s presidency.

The Department of Homeland Security’s claims a record arrests and deportations since Trump took office. In an April 28, 2025, press release, it claimed that immigration arrests and deportations had “already surpassed the entirety of Fiscal Year 2024 [numbers], and we’re just 100 days into this administration.”

Trump’s border czar, Tom Homan, stated in late May 2025 that the administration had deported around 200,000 people over four months; the Department of Homeland Security reported over 207,000 deportations as of June 11, 2025. The New York Times indicate over 200,000 deportations since Trump’s return to office.

Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) reports that the Trump administration recorded fewer than 932,000 deportations; other sources suggest a figure closer to 1.5 million deportations.

TRAC reports that “deportations during a similar period [February-May 2024] under President Joe Biden’s administration” 257,000 people were deported. Pres. Barack Obama deported 3 million noncitizens over his two terms in office. This is, according to one source, “more than any other president in American history.”

In comparison, Pres. George Bush removed about 870,000 people; Pres. Bill Clinton, about 2 million; and Trump about 1.2 million people during his first term.

Trump, like many presidents and politicians before him, knowns that foreign and foreign-born Americans are a perfect target. And U.S. history is the history of targeting the other as the enemy, often resulting in deportations and/or forced migrations.

+++

Americas were divided over slavery, not only whether it was immoral if not illegal, but whether to expand it from the South to the new states in the West (e.g., Kansas). A decade before the Civil War started, the abolitionists were divided over what to do with the slave population, especially when they were freed. In 1854, future president Abraham Lincoln gave a speech in Peoria, IL, arguing:

“I should not know what to do as to the existing institution [of slavery]. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia, to their own native land.”

When in office in 1861, he ordered a secret trip to the isthmus of Chiriqui in the northern part of today’s Panama to assess the viability of relocating former slaves. The land was owned by Ambrose Thompson, a wealthy shipbuilder from Philadelphia, who proposed it as a refuge for freed slaves. As one source notes, “The slaves would work in the abundant coal mines on his property, the coal would be sold to the Navy, and the profits would go to the freed slaves to further build up their new land.”

Most insightful, Zaakir Tameez, a recent Yale Law School graduate, is quoted by New York Times op-ed writer Jamelle Bouie:

The colonization movement proposed abolishing slavery or winding it down over a period and then effectively deporting formerly enslaved people to Africa. The colonization societies could not imagine white and Black people living as equals in this country or African Americans being a political body in this country. So their proposal was just to mass deport them.

Before there were attacks on Mexican and Mexican Americans, Chinese immigrants were singled out. In the spring of 1882, Congress passed — and Pres. Chester A. Arthur signed — the Chinese Exclusion Act. It banned Chinese immigrating from to the U.S. for ten years.

In the wake of California’s gold rush, thousand of Chinese people immigrated to the U.S. seeking a better life. Michael Luo, writing in The New Yorkers, notes that by 1880, “the Chinese population in the country exceeded a hundred and five thousand.” He adds, by “the mid eighteen-eighties, during probably the peak of vigilantism, at least a hundred and sixty-eight communities forced their Chinese residents to leave. In one particularly horrific episode, in 1885, white miners in Rock Springs, in the Wyoming Territory, massacred at least twenty-eight Chinese miners and drove out several hundred others.”

Singling out still other immigrants, the U.S. undertook a series of select deportations as part of what’s recalled as the Palmer Raids conducted in November 1919 and January 1920. Adam Hochschild, writing in The New Yorker, noted, it was “the country’s first mass deportation of political dissidents in the twentieth century.”

Pres. Woodrow Wilson ordered the U.S. Department of Justice to capture and arrest suspected radicals, especially anarchists and communists, and deport them. Palmer’s agents, led by J. Edgar Hoover, arrested nearly 10,000 people in seventy cities and deported nearly 600 people, including the anarchist Emma Goldman.

Trump’s rage against Mexican migrants is not the first of such campaign against Mexicans and Mexican Americans. During the Depression, Pres. Herbert Hoover’s provocative slogan, “American jobs for real Americans,” kicked off a spate of local legislations banning employment of anyone of Mexican descent. The majority of deportations occurred between 1930 and 1933 as police descended on workplaces, parks, hospitals and social clubs, arresting and dumping people across the border in trains and buses.

As the Guardian reports, “Nearly 2 million Mexican Americans, more than half U.S. citizens, were deported without due process. Families were torn apart, and many children never again saw their deported parents.” Deportations took place in border states like California and Texas as well as heartland states like Michigan, Colorado, Illinois, Ohio and New York.

If deportation is one way to force unwanted people from the U.S., blocking immigrants is a way of keeping such people out. In June 1939, the German ocean liner St. Louis and its 937 passengers, almost all Jewish, were turned away from the port of Miami, forcing the ship to return to Europe; more than a quarter died in the Holocaust.

As the Smithsonian magazine reminds readers, Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt “repeated the unproven claims from his advisers that some Jewish refugees had been coerced to spy for the Nazis.” It then quotes FDR:

“Not all of them are voluntary spies. It is rather a horrible story, but in some of the other countries that refugees out of Germany have gone to, especially Jewish refugees, they found a number of definitely proven spies.”

The belief that refugees posed a serious threat to national security was not limited to FDR but was shared by the State Department and the FBI. Immigration restrictions tightened as the refugee crisis worsened. As the Smithsonian notes, “Wartime measures demanded special scrutiny of anyone with relatives in Nazi territories—even relatives in concentration camps.”

+++

What Trump and many others forget, America was never a “white” nation.

When the first Europeans, be they Spanish in St. Augustine, FL; the Dutch carrying enslaved Africans to Jamestown around 1619; or the English in New England, arrived in what is today’s American, the country was already populated with indigenous peoples. Enormous efforts were made to irradicate the Native peoples including horrendous wars, mass displacements and forced colonization on reservations. Native peoples didn’t receive citizenship until 1924.

Often forgotten, at the time of the Revolution, the total population was approximately 2.6 million, of which 566,000 were of African descent and 90 percent were enslaved. As of 2024, the U.S. was a multi-racial, multi-ethnic society of 332 million people. It was a mixture of non-Hispanic whites = 58.4 percent; Hispanic/Latinos = 19.5 percent; Blacks = 13.7 percent; Asians = 6.4 percent;

Native American/Alaskans = 1.3 percent; and Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders = 0.3 percent.

In just two decades – in 2045 – the U.S. will become “minority majority” nation. During that year, whites will comprise only 49.7 percent of the population.

This well may be freaking out Trump and other white nationalists. He inherited more than money and a real-estate business from his father, Fred Trump. Father Trump, like his son, did not serve during war – in Trump senior’s case, WW-II — but made a fortune from the postwar housing boom. Few remember that in 1927, Trump the elder was arrested with six other racists at a Ku Klux Klan rally in Queens, NY. Senior Trump, 21 at the time, was a long-time racialist and, like his son, a real-estate conman.

On Memorial Day 1927, supporters of Mussolini’s Italian fascism and Klansmen rioted in the Bronx, killing two Italian men. In Queens, 1,000 white-robed Klansmen marched through Trump’s Jamaica neighborhood, and he was busted. The white nationalist confronted 100 policemen and, as a local report claimed, “staged a free-for-all.” Trump senior reportedly wore a Klan robe and, while arrested, no charges were brought against him.

Marx once noted, “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce.” But what if history repeats itself a third or fourth time?

No comments:

Post a Comment