A political history of the Democratic Socialists of America, 1982-2025

[Editor’s note: Cyn Huang, a member of the Bread & Roses caucus inside the Democratic Socialists of America, will be speaking at Ecosocialism 2025, September 5-7, Naarm/Melbourne, Australia. For more information on the conference visit ecosocialism.org.au.]

Republished from The Call. This article is a modified version of an essay that appears in the new book, A User’s Guide to DSA (Labor Power Publications, 2025).

Few members of DSA know much about the history of our organization, but many of us understand how special it is. There is no single other group in the entire country, even including unions, that has a large base of participants with an internal democracy capable of seriously contemplating major political issues and then devising a plan to organize working people to fight for their own interests as a class. Yet even though it is theoretically possible for us to do so in DSA, the American socialist movement is still small and politically immature.

Historically speaking, there are fundamentally two DSAs: pre-Bernie DSA (1982-2014) and post-Bernie DSA (2015-present). Only a tiny portion of DSA members were organized socialists before the Bernie Sanders presidential campaign revitalized the idea of “democratic socialism” in 2015 (myself included), and many active members now only became socialists in the last few years or months. But why did people join DSA instead of any other socialist or “left” organization? What was DSA like before it was flooded with newly-radicalized young people? And how did those new members mold the organization into the DSA we know now?

The before times (1982-2011)

Given that DSA’s modern rebirth is owed to the two presidential campaigns of democratic socialist Bernie Sanders, it’s fitting that DSA is directly descended from the Socialist Party of America, the party line on which Eugene Debs received nearly a million votes in two of his campaigns for president (even while he was in prison for opposing World War I!). DSA was formed in 1982 as a merger of the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC) and the New American Movement (NAM). DSOC was a faction led by Michael Harrington that had split off from the Socialist Party of America, and NAM was founded in 1971 as a non-vanguardist socialist-feminist organization. At DSA’s founding convention in Detroit, it had 6,000 members.

Michael Harrington was the chairman and figurehead of DSA from its inception until his death in 1989. He is known for being a prolific public speaker and touring the country to promote his vision of socialism. Marxist feminist author Barbara Ehrenreich served as co-chair, as did some other high-profile leftists like professor and author Cornel West. Several elected officials were also members of DSA, like Congressman Major Owens, Congressman Ron Dellums, and NYC Mayor David Dinkins (another fitting historical parallel, given Zohran Mamdani’s recent campaign).

What were DSA’s politics at the time? “Democratic socialism” was presented in contrast to communist groups that had strict internal discipline, many of which defended the authoritarian practices of the Soviet Union. DSA was also home to many “labor Zionists” who advocated for a social democratic state of Israel, but at the expense of the rights of Palestinians. Throughout the ‘80s, DSA was heavily involved in solidarity campaigns with Sandinistas in Nicaragua and leftist rebels in El Salvador, and the youth wing was active in the movement against apartheid in South Africa.

Crucially, DSA favored the electoral strategy of “realignment,” meaning using the Democratic Party as a vehicle for working-class power and reforming it from within. This approach stood in contrast to that of Bernie Sanders — who won his race for Congress in 1990 as an Independent and at that time was openly critical of DSA from the left — as well as that of the socialists who formed and led the US Labor Party from 1996-2001. DSA was friendly to prominent labor movement figures and avoided being perceived as intervening in internal union disputes. Although DSA didn’t back Jesse Jackson for president in 1984, DSA was part of the Rainbow Coalition that supported Jackson’s second campaign in ‘88.

The collapse of the Soviet Union culminating in 1991 was a world historic setback that brought on an era of desolation for the international socialist movement. Many socialist and communist groups dissolved or, like DSA, barely stayed above water throughout the ‘90s and 2000s. Although DSA grew to 10,000 paper members, it was not functional in most of the country, particularly due to the loss of a strong, charismatic leader like Harrington. It was the Young Democratic Socialists (DSA’s youth wing, now called YDSA) who were active in many cities and worked with allied groups like Jobs with Justice. From about 2001-2014, YDSA had a skeleton crew who kept the lights on and developed comrades who went on to lead DSA.

Pre-rebirth (2011-2015)

One of those leaders from YDSA was Maria Svart, who served as YDSA Co-Chair and then was a member of the DSA’s National Political Committee (NPC), the highest decision-making body in between conventions. She was hired as National Director in 2011 and was in charge of DSA through the rebirth era.

This period saw the emergence of several forceful popular movements: Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring in 2011, Fight for $15 in 2012, and Black Lives Matter in 2013. Occupy in particular was instrumental in using class-conscious framing (“We are the 99%”) to legitimize social democratic policy demands like taxing the rich. The socialist movement was also gaining steam outside of DSA. Jacobin magazine had just been founded by Bhaskar Sunkara in 2010, which organized local reading groups and helped popularize socialist analysis to the left of DSA’s realignment model. Kshama Sawant was elected to the Seattle City Council in 2013, representing the Trotskyist group Socialist Alternative and serving as a modern model of a socialist politician-as-organizer.

The formation of the Left Caucus in 2014 created the space for more left-wing ideas that challenged some of DSA’s longstanding assumptions. The Left Caucus was an internal group of DSA members who advocated for running candidates as explicit socialists, adhering to a standard program, and leaving the neoliberal Socialist International. They were also friendly to the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel, but explicit anti-Zionism was at that point still difficult to talk about in DSA.

In early 2015, DSA began a campaign to draft Bernie Sanders to run for President called “Run, Bernie, Run.” Across several cities, small groups of DSA members tabled outside events where Bernie spoke and flyered the crowd.

Rebirth (2015-2018)

In April 2015, Bernie Sanders announced he was running for president in the Democratic primary, challenging the presumed front-runner Hillary Clinton. It was widely considered a long-shot campaign. No one knew just how earth-shattering this race would be — including Bernie himself, who first made the announcement with no fanfare to a small audience of journalists, which was comically dull in retrospect.

That summer, Bernie’s popularity skyrocketed, and DSA membership began to grow steadily. Over the next two years, Jacobin reading groups turned into DSA chapters. Online leftist figures like the hosts of the Chapo Trap House podcast (which started in March 2016), Twitter personality “Larry Website,” and Jacobin writers encouraged their followers to join DSA.

As we watched Bernie dare to speak the truth about the billionaire class and then suffer lies and slander from the liberal power-brokers, many left-leaning millennials like me underwent a total paradigm shift. His platform — particularly Medicare for All, free college, and opposition to the finance, war, and fossil fuel industries — raised expectations where Obama had brought them to the floor. Politics became fundamentally re-polarized: it was Bernie against the wealthy elite, and we knew what side we were on.

When Bernie lost, we were devastated, but it seemed like a foregone conclusion that Hillary Clinton would be the next president. Extremely few people in the left-liberal political universe seriously worried that Trump would win. And then he did.

People were panicked and sick with grief. Protests broke out around the country on election night. DSA membership exploded immediately, growing from 8,500 on Election Day to 21,000 by May 2017. I joined in January after I saw a mainstream news article saying all the Bernie supporters were flooding into DSA. For the vast majority of us, this was our first socialist organization. New members had a wide diversity of ideological leanings, from progressive activists and Democratic Party refugees to more hard-left inclinations like anarchists, Maoists, and Leninists, some of whom came from other groups like the International Socialist Organization.

People quickly realized that we were inheriting a loose, decentralized organization where you could mostly just take initiative and do what you wanted. Some people wanted to change that, but there were (and still are) very few DSA members who had been educated in a more centralist model and had the political development or leadership skills to carry it out. Horizontalism was also a particularly popular perspective from both the Occupy Wall Street legacy, as well as a reaction to bad experiences with hard-left democratic centralist groups. This trend fit well with people’s existing inclinations towards individualism that are hegemonic in our liberal culture. Debates arose about what collective discipline we should expect from each other versus the “big tent” nature and member autonomy. At the national level, these debates were heavily influenced by fears among staff and established members that the new wave of members could drive DSA too far off course or even destroy it.

The Trump administration started off with a bang: the “Muslim ban,” which was quickly thwarted by protests at airports and a taxi driver union strike. This proved the potential for popular left-wing resistance to Trump’s agenda, despite the emergence of right-wing groups like QAnon and the Proud Boys.

At the 2017 DSA Convention, the new generation of members officially took over. Delegates passed three proposals that defined DSA as distinct from the liberal #Resistance:

- enshrining DSA’s support for BDS,

- leaving the Socialist International, and

- launching a Medicare for All campaign, which was the first organizing project of the new DSA that coordinated members across chapters.

Echoes of rebirth (2018-2020)

As we got our footing as a movement reborn, the overwhelming sentiment at the time was “anything is possible.” We had just lived through the utter upheaval of political norms, and we saw new breakthroughs all around us. The clearest example of this was in June 2018, when Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC), a millennial Bernie-supporting barista calling herself a democratic socialist, ousted the second most powerful Democrat in Congress, Joe Crowley, in a massive upset victory. (The day she won still holds the record for most new DSA members in a single day.) A few months later, she joined youth activists in the Sunrise Movement who were occupying the office of top Democrat Nancy Pelosi. Bernie supporter Rashida Tlaib also won her primary that year and became the first Palestinian American, and one of the two first Muslim women, along with Ilhan Omar, to ever be elected to Congress. AOC, Rashida, Ilhan, and Representative Ayanna Pressley formed “The Squad,” which, despite its hesitancy to directly confront party leadership, many DSA members respected as the first recognizable left opposition to the Democratic Party establishment in our lifetimes.

Although AOC and Rashida were members of DSA, as an organization we didn’t have any serious claim of ownership or contribution to what The Squad did. AOC and Rashida weren’t active DSA participants, and their victories weren’t really DSA campaigns. The first major truly home-grown DSA electoral victory was Julia Salazar, who won the Democratic primary for New York State Senate in September 2018 (and then won the seat in November). Then in 2019, Chicago DSA ran and won a slate of six democratic socialist Alderpersons on the Chicago City Council. In 2020, New York City DSA ran and won a slate of seven democratic socialists for New York State Assembly (including Zohran Mamdani). Chapters around the country built their electoral programs, passing ballot measures and electing our own members to local office.

This period also saw the historic wave of educators’ strikes set off by the West Virginia illegal wildcat strike in 2018. Oklahoma and Arizona teachers struck in 2018, and teachers in Virginia, Denver, Los Angeles, Oakland, and Chicago struck in 2019, inspiring other #RedForEd educator workplace action around the country. Many of the people organizing and leading these strikes were DSA members or Bernie supporters. Like the new electoral victories, we weren’t just cheering from the sidelines – we were major actors in the site of struggle, both as rank-and-file militants and as active supporters in the DSA-coordinated solidarity campaigns.

The 2019 DSA Convention focused on two core questions:

- Should DSA be a decentralized network of chapters, or is there value in a strong, unified national organization?

- Should DSA orient to people who are already radicalized and the “most marginalized,” or should we orient to the whole working class and those with strategic leverage within it?

By that point, at least seven national caucuses had formed, representing a variety of views across the anti-capitalist left spectrum. Ultimately, the most horizontalist, prefigurative perspectives did not prevail, but many of those same complications and debates persist to this day.

Most of this modern wave of DSA members had only ever engaged with their local chapter rather than the national organization — until we debated the question of endorsing Bernie’s 2020 presidential campaign. Despite his essential role in rebirthing DSA, a sizable minority of members (mainly from the most hard-left and anarchist wings of DSA) balked at the idea of getting involved immediately. Many critics cited process concerns, while some were more upfront about their skepticism of Bernie and his fans’ “reformist” politics or even of electoral campaigns in general. But 76 percent of DSA members in an online membership pollsupported embarking on a “DSA for Bernie” campaign. After Bernie launched his second run, from about March 2019 through March 2020, dozens of chapters were participating in the same thrilling national project simultaneously — canvassing, holding debate watch parties, bringing in new recruits, and developing socialist leaders.

Words simply cannot capture the psychedelic high of optimism we felt when Bernie won the Nevada primary in February 2020 — nor the sickening misery and despair that followed it just a week later when he lost South Carolina and then most of the states on Super Tuesday. Many of us had our existential foundation and hope for the future riding on his campaign, and everything we had poured our hearts and souls into all came crashing down so quickly. At the exact same time, public life began shutting down due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Millions of people were laid off practically overnight. DSA gatherings turned into Zoom calls. Suddenly, we were all alone, despondent, and scared.

COVID era (2020-2023)

We didn’t have long to mourn Bernie’s loss before a new wave of Black Lives Matter protests completely swept the country in response to the murder of George Floyd. Millions of people marched in the streets for weeks, comprising the largest mass mobilization in US history. This politicized and radicalized many working-class people, but in some DSA chapters it also brought on intense discussions about race and racism, the difficulty of which was exacerbated by anti-social behavior due to isolation and exclusively online interaction during the pandemic. The red skies of the unprecedentedly devastating 2020 wildfires — obviously brought on by accelerating climate change — added to our existing sense of overwhelm and disorientation about the future.

DSA membership continued to grow until it reached a high water mark of 93,000 in early 2021 after a big membership drive. The growth from this drive was difficult to sustain, as it was disconnected from a particular organizing project and lacked dedicated, political onboarding. And now without a high-profile democratic socialist agitating against the liberal establishment, and without the terror of Trump in office, DSA began a nearly four-year bleed of members.

Not long after the 2021 convention — held online-only due to COVID — an internal war was ignited when Representative Jamaal Bowman voted to increase funding for Israel’s Iron Dome. Because Bowman was a DSA member and DSA had endorsed his campaign, some members launched a petition to censure and expel him. Pouring fuel on the fire, the DSA BDS Working Group began to act like an independent external organization putting pressure on DSA, and the NPC disciplined them as a result. Although the NPC released a statement admonishing Bowman (and AOC, who voted “present” on the bill), this incident raised debates that are still ongoing about how to handle it when our politicians act at odds with our policies or principles, how to properly raise dissent within DSA, and how to handle sub-groups of DSA going rogue.

In contrast to those internal struggles, COVID brought on a labor shortage that led to an inspirational upsurge in worker militancy and a renewed interest in labor within DSA. In 2020, DSA and the United Electrical Workers founded the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOC), an independent project to provide resources and training to everyday people who decide they want to organize where they work. In 2021, YDSA began the “Rank-and-File Pipeline Project” to get young people to work in strategic industries. Dozens of DSA members got jobs at UPS to join the Teamsters and elected the reform slate led by Sean O’Brien against the conservative Hoffa legacy slate. Starbucks organizers and Amazon organizers won their first union elections in major triumphs over the corporate giants. The 2022 Labor Notes Conference was electric, with young energy and hope from thousands of first-time attendees. In 2023, reformers took the leadership of United Auto Workers in a massive upset victory, including Shawn Fain as President. DSA chapters also supported countless local strikes, and nationally we ran “Strike Ready” campaigns to support the anticipated strikes of UPS and the Big Three auto manufacturers. After the history-making Stand Up Strike, UAW President Fain called for unions to prepare for a general strike on May Day 2028.

But this period quickly encountered setbacks. The YDSA jobs pipeline came to a screeching halt after a convention decision failed by one vote. Teamsters within DSA became bitterly divided about the existing reform caucus, Teamsters for a Democratic Union, and its cautious orientation to the disappointing President O’Brien. Unite All Workers for Democracy, the UAW reform caucus that had elected President Fain, struggled to resolve deep internal differences and eventually dissolved in 2025.

A political shift (2023-2024)

At the 2023 DSA National Convention, delegates elected an NPC with more representation from “left” tendencies than ever before (including me, a member of the Bread and Roses Caucus) — enough that the more moderate caucuses could not form a governing majority on their own. This seriously disrupted the typical dynamic in which the National Director and other directors were in the driver’s seat, controlling the flow of meetings and the flow of information. Many of us were critical of directors’ more moderate politics and distrusting orientation to members, and we had enough votes to pursue a greater level of transparency and openness in the national office.

Maria Svart resigned as National Director in January 2024. At that time, the NPC was beginning to confront a steep budget shortfall, which raised a massive controversy over staff layoffs and the question of what employees should expect when their employer is a socialist organization (mirroring similar debates in the labor movement). In just one year, 18 out of over 30 staff quit or were laid off, including every single director who had served in their role under Svart, signaling staff-side solidarity between directors and unionized staff against the member-elected NPC. This turnover resulted in some operational dysfunction but also a noticeable culture shift.

This new NPC also bucked expectations of the past by deciding not to unconditionally endorse AOC in June 2024. Many DSA members had grown increasingly frustrated by her fair-weather attitude and proximity to the Democratic Party establishment, but the NYC-DSA chapter was committed to preserving their relationship with AOC. This disagreement ripped open a divide between the NYC chapter and the national organization (rooted primarily in that NYC is dominated by caucuses that are now a minority on the NPC), which led to the NYC-DSA leadership interfering with national DSA having a relationship with Zohran Mamdani in his campaign for mayor a year later.

Although the political divides within DSA remain deep, the NPC has matured into a multi-caucus parliament, and people are consciously aware of this dynamic and lean into it in a healthy way. Assembling a majority bloc is potentially within reach for all tendencies, which incentivizes people to try to meet in the middle and persuade others of their view. This negotiation process is essential because it reinforces the democratic legitimacy of the body, and it makes it difficult for either wing to act impulsively and arrogantly.

Throughout these changes was the seismic shift in popular consciousness about Palestine following the Hamas attacks on October 7, 2023. National DSA struggled to find its niche in a protest movement with an activist layer dominated by sectarian hard-left organizations and Palestinian solidarity groups that were unhappy with DSA for associating with politicians like Bowman. We had difficult debates about how to relate to these groups, how to talk publicly about political violence, and what should be done about DSA members who hold Zionist views. Despite these challenges, chapters were consistently present in the mobilizations against Israel’s genocide in Gaza, and YDSA was a major presence in protest encampments that sprung up on college campuses around the country, where our members fought hard for principles of democracy within the encampment groups.

Trump’s second term (2024-present)

Leading up to the 2024 presidential election, DSA members had intense debates about how to resolve the perennial “lesser evil” contradiction: a Trump presidency would surely bring terror on the world, but how could we in any way condone Biden, the perpetrator of a genocide and an enemy of the working class? The NPC eventually agreed on a statement that amounted to, “This choice sucks; join DSA so we can have a good option someday.”

When Trump won, popular frustration and dissatisfaction with the Democratic Party was palpable almost immediately. And for the first time since 2021, DSA had net positive membership growth – and it’s staying strong still. Down from a low of 64,000 in October 2024, we recently got back up above 80,000. Since November, new members have been filling chapter meetings like nothing we’ve seen since before COVID. Their political inclinations are also noticeably different than the new member waves in the past: on average, they are excited about the prospect of an alternative to the Democratic Party.

As of this writing, Zohran Mamdani has just won the Democratic primary for mayor of New York City. Much will be said elsewhere about what this accomplishment means for our movement, but it will undeniably be the defining event of this period in DSA’s history.

Beyond

For decades, it has been an almost unquestionable fact that the Democrats are the only alternative to the Republicans, but now we socialists are constantly having conversations with regular people who are fed up and hungry for something new. It’s no surprise that the ambition of building a new party for the working class is a central topic of debate right now in DSA.

However, the American working class will struggle to take advantage of the opportunities around us; we are tragically historically disorganized. Decades of red scare drove communists and socialists out of the labor movement, and professional activist non-profit businesses have replaced true grassroots political organizations. Most popular protest movements completely neglect to cohere working-class people into any kind of formation that can persist and grow beyond single-day mobilizations.

That is why, despite all our challenges and limitations, a vibrant, democratic, multi-tendency, and politically independent DSA is so desperately needed to chart a course for the next era of history for the working class.

This article is from the new book A User’s Guide to DSA: 5 Debates That Define the Democratic Socialists ($15, 460 pages, published by Labor Power Publications). A User’s Guide to DSA features original and often conflicting perspectives from the different tendencies on the front lines of building DSA — not as a social media flame war, but as a serious dialogue aimed at sharpening our strategy to build working-class power.

Laura Wadlin is an elected member of the DSA National Political Committee (2023-2025) and a member of the Bread and Roses caucus. She teaches English as a Second Language at Portland Community College and is a shop steward in AFT Local 2277.

United States: Lessons from the DSA Convention

In the following remarks by Paul Le Blanc, the author reflects on what he could learn from the current state of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and the possible way forward after having participated as an observer at the recently concluded DSA National Convention 2025, which was held in Chicago from August 8 to 10.

These remarks are now being published simultaneously on LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal and Communis with Paul Le Blanc’s authorization.

***

Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) currently has grown to more than 80,000 members, with many joining after Trump's second-term victory and Zohran Mamdani's win in the Democratic Party's New York City mayoral primary. According to one participant-observer (Stephan Kimmerle, a delegate from Seattle), “a wave of radicalization is bubbling up across the US reflecting a surge of resistance against Trump, the genocide in Palestine, and a new cycle of socialist electoral campaigns. The left-wing of these movements is finding an organized expression in DSA. All signs point to DSA being on track to make a new surge forward, likely surpassing 100,000 members in the coming months.”

It is important to understand that 100,000 represents the membership on paper, not an active membership. My native Pittsburgh illustrates the larger reality. In Pittsburgh, the paper membership has fluctuated around 700. Of these, between 400 and 500 have been members “in good standing,” that is, those who have paid their dues. Of those, roughly 10% could be considered active – in the sense that they attend monthly membership meetings (which are hybrid, in-person/on-line attendance) and/or are involved in one or another working group. I have begun to attend monthly meetings in-person, and I have generally seen between 50 and 80 participants at each.

This would translate into a national total of active DSA members in the range of 8000-to-10,000, which is still a substantial force and certainly makes DSA far larger than any other left-wing group in the United States today.

An invaluable source for those seeking a political understanding of DSA is a new collection edited by Stephan Kimmerle, Philip Locker, and Brandon Madsen, A User’s Guide to DSA: 5 Debates That Define the Democratic Socialists. This provides over 450 pages made up, primarily, of 38 articles representing a full range of opinion within DSA. A paperback can be acquired for $15, an e-book for $9.50.

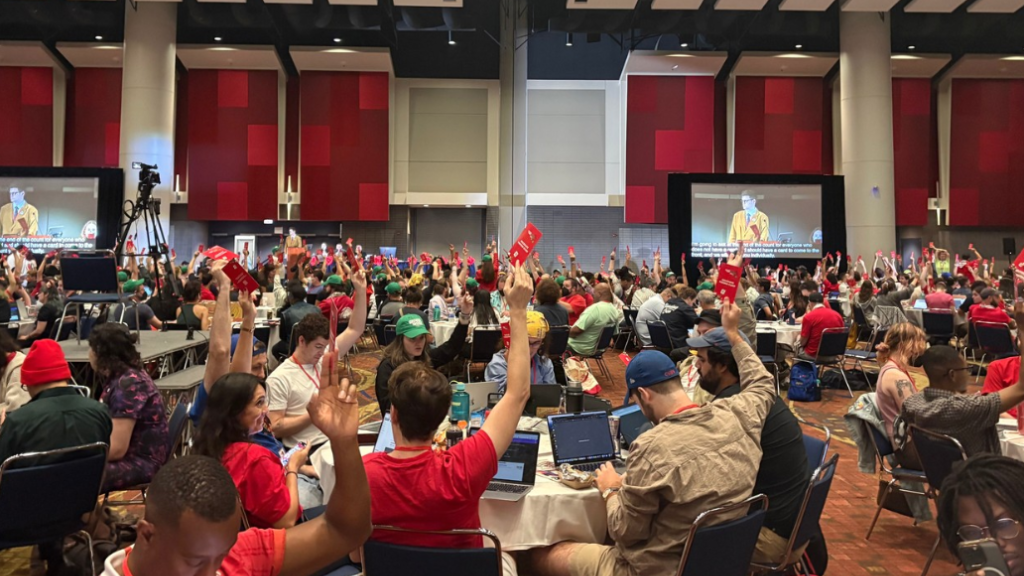

Who was at the Convention

The highest decision-making body within DSA is the delegated national convention, held every other year, which takes place after several months of written and oral pre-convention discussion. Conventions select a national leadership, make decisions on structure, policy, campaigns, etc. They are highly structured, heavy on procedure (some feel overly heavy), but on the other hand they are relatively democratic.

At the 2025 national convention in Chicago (August 8-10), there were approximately 1500 people in attendance — almost all of whom were members of DSA, and the overwhelming majority of whom were elected delegates. Looking at how many voted on the various resolutions and motions brought before the body, the number generally fluctuated between 1100 and 1200, with the high-point that I was able to find being 1229 — which would place the number formal observers (like me) and guests at around 271.

The age range was overwhelmingly on the young side — perhaps a few teenagers, but most in their 20s, 30s, and 40s. Those in their 50s and 60s were relatively fewer in number, with only a sprinkling in the 70s and 80s bracket.

While a majority of those present could be identified as “white,” there were significant numbers of Hispanic, African, South Asian, East Asian, and Middle Eastern extraction. The gender balance struck me as fairly even, including a significant percentage of those identifying as trans and “non-binary.” What especially stood out for me was that the vast majority of those present appeared to understand themselves to be part of an occupationally diverse working class. It was class identity that seemed to be central in the discussions at the convention.

This meant that topics common to many left-wing conferences (analyses of a variety of identities, modern-day abolitionism, race and anti-racism, feminism, gay rights, explanations of theory, the environmental crisis, etc.) were not the focus of discussion here. Some of these things were, in fact, already integrated into the perspectives of the participants, but the vocabulary and focus of their discussions had to do with the practical political application of a working-class oriented Marxism seeking to replace capitalism with socialism..

Political orientations at the Convention and within DSA

It seemed a fairly serious body of convention participants — most of those in attendance remained present during the sessions at which the various resolutions were presented, discussed and debated, and voted on. There was a numbing quantity of proposed amendments (some adopted, some not), procedural motions, points of order, challenges to decisions of the chair, etc., etc. — turning much of the convention into a fairly grim slog. But most of the comrades seemed to stay with it and were able to cast knowledgeable votes when the time came to vote.

While I have been inclined to be distrustful of the various caucuses in the organization — initially perceiving them as essentially parasitic, and unhelpfully artificial — my experience at the convention has now caused me to see them as having become a relatively organic component of DSA, helping foster a democratic culture in DSA and contributing to the organization’s growth and development. Although there was initially a tendency to group the various caucuses into a Left Bloc and a Right Bloc, the complexities of the actual situation suggest three blocs — while also requiring a recognition that the situation remains dynamic and fluid, and that on-the-ground complexities push against reducing the organization to any cut-and-dried schemas. But first, let us identify the three blocs. (This three-bloc schema is drawn from a convention report by Stephan Kimmerle, who belongs to the minority current within Reform and Revolution. I have felt a need, however, to modify the way he characterizes the three blocs, in order to align it more closely with my own perceptions.)

- A moderate wing that emphasizes mass work, aims for DSA to resonate with a broader working-class audience, and adopts an opportunistic approach toward DSA’s elected officials, and inclines toward “progressives” and liberals among Democratic Party politicians and among leaders in the labor movement. This wing reflects some continuity with such original founders of DSA as the late Michael Harrington. Until recently, their orientation tended to be predominant in DSA, but this has changed dramatically. Caucuses in DSA representing this orientation include Groundwork and the still-sizeable Socialist Majority Caucus. On the right fringe of this wing is North Star, quite small but more explicit in its adherence to the Harrington tradition.

- A far-left wing that is inclined to break decisively from liberal-reformist perspectives favored by the moderate wing. It generally reflects the sentiments of left activists within the Palestine movement and also contains advocates for a campist variation of “anti-imperialism” — which essentially means aligning with, and being more or less uncritical of, all forces who are in the “camp” that opposes the US empire. (Within that “camp” are authoritarian dictatorships — some claiming to be socialist, and others that are conservative and openly anti-socialist, in some cases ultra-religious.) Included in this wing of DSA are Red Star and Springs of Revolution.

- A Marxist center-left that seeks to merge an orientation towards the mass of working-class people with a strategy aimed at building an independent socialist party, while promoting class struggle and socialist ideas within labor and social movements. This includes Bread and Roses, Reform and Revolution, and Marxist Unity Group. Yet within each of these there is a spectrum of perspectives — with an explicit division opening up between minority (the former leadership) and majority within Reform and Revolution. Some elements of Bread and Roses are concerned to avoid a final rupture with the moderate wing. Some elements of Reform and Revolution and Marxist Unity Group are not inclined to separate themselves from perspectives of the far-left wing.

Related to the complexities just alluded to, there is a positive tendency within the various caucuses for comrades to listen and give serious consideration to what comrades outside of one’s own caucus have to say. There are, also, some serious-minded caucus members who end up shifting to a different caucus if they are persuaded of the merits of that caucus’ perspectives. We have seen that the organization as a whole has shifted from the moderate orientation to a more left-wing orientation. At the 2023 convention, and again in 2025, there have been further tilts leftward as a radicalization process continues to unfold within DSA — reflecting what is happening in the larger world outside of DSA.

Recently new caucuses have come into being. The Carnation Caucus has advanced a four-year program designed to place the organization in an orbit blending center-left Marxism with far-left perspectives, insisting that DSA itself should be considered a political party. Another newly formed caucus self-describes as “Liberation — A Marxist-Leninist-Maoist Caucus,” advancing positions that have yet to make sense to many DSAers.

There are also caucuses that do not fit neatly into the three blocs — in some cases tending to straddle two of the blocs, in other cases evolving in a manner inconsistent with placement in any of the blocs. In the former category there are two caucuses that have succinct descriptions in A User’s Guide to DSA. The Communist Caucus (with which I feel some affinity) is described this way: “A multi-tendency communist caucus. They focus mainly on labor and base-building, including tenant organizing.” Emerge is described similarly: “A multi-tendency communist caucus in NYC-DSA. They are active around questions of anti-imperialism and tenant organizing.” There is also the anarchist-influenced Libertarian Socialist Caucus, a serious formation with popular projects but which, as the editors of A User’s Guide to DSA comment, “makes it an outlier on the left of DSA — most other members of the organized left of DSA come from caucuses that claim Marxism as their foundation.”

I suspect that most of DSA nationally is similar to the DSA branch in Pittsburgh — a majority of members belong to no caucus. But they value the ideas, contributions, and commitment of various caucus members and are quite prepared to elect a high proportion of them to represent the Pittsburgh branch as delegates to the national convention. Still, they are unaligned and inclined to do their own thinking, under the dual impact of larger events and of their own experience.

Debates, decisions, discussions

The three days of the DSA convention were too tightly packed to allow for a thorough blow-by-blow account, which could be adequately presented, perhaps, in a book, but not a relatively brief account such as this. That is especially true of the more than 13 hours of Deliberation Blocks — thick with reports, resolutions, amendments, procedural motions, points of order, votes and more among 1100 to 1200 delegates.

These unavoidable monstrosities were distributed in the mornings and afternoons of the three days, interspersed with a keynote address here, a Programming Block or two there, acceptance speeches of some comrades who had been elected to internal DSA positions, and even some very nice singing, at a couple of points, from the “Sing in Solidarity” choir. Altogether there is simply too much to cover except through quick notes and relatively impressionistic sketches.

The debates at the convention tended to focus on several concerns.

- What structures and policies would ensure greater membership participation and control within DSA and also greater cohesion and effectiveness.

- How independence from Democratic Party establishment could best be accomplished — with attention especially focused on the 2028 Presidential election.

- What should be expected of candidates that DSA endorses. This also involves what should endorsement consist of? (Comrades working on the campaign? Ongoing consultation and collaboration between DSA and the candidate?) What should be expected of an endorsed candidate? Should they run as an open socialist, on a platform that has DSA input? If the candidate wins, how can accountability be ensured?

- How far to the left should DSA move in order to be true to its core socialist principles.

- How best to realize a genuine and meaningful internationalism (involving such issues as imperialism and anti-imperialism, relations with various organizations and coalitions, solidarity with Palestine and specifics of anti-Zionism, and the issue of “campism”).

Debate took place in conjunction with motivating, supporting, or opposing resolutions about to be voted on. Some sense of the direction in which the organization is moving is conveyed by one experienced Pittsburgh DSA delegate in this way:

- The eyes of our organization are set firmly towards 2028

- We will be building towards a May Day 2028 action, and have outlined a series of tasks that our organization must do to be ready in: R30: Fighting Back in the Class War: Preparing for May Day 2028, as amended by R30-A01: Tenants & Workers Together in 2028

- We will begin the process to plan to support a Labor-Left presidential candidate in 2028 through R33: Unite Labor & the Left to Run a Socialist For President and Build the Party (unamended)

- Fighting Fascism: We will be standing up to Trump by

- Standing up against deportations and making Abolish ICE a priority through R26: Fight Fascist State Repression & ICE

- Continuing the “Trump Administration Response Committee” (TARC) with work outlined in R05: Fight Fascism, Build Socialism

- Reaffirming Commitments to Palestine & Internationalism:

- Reaffirm our commitment to internationalism

- Reaffirmed our commitment to BDS work through passing R36: A Unified Democratic Socialist Strategy for Palestine Solidarity

- Passed the Anti-Zionist resolution unamended R22: For a Fighting Anti-Zionist DSA

- We will update our Program

- A commission will be established to update Workers Deserve More for the current political situation by passing R34: Workers Deserve More, Forever: For a Coherent and Continuous Program Befitting DSA’s Political Growth unamended.

- Participating in local elections at all levels remains a priority

- Participating in local elections at all levels will remain a major focus for our organization, convention decided to hire 2 more electoral staffers.

- Federal endorsements by National will now require thoughtful communication and for the NPC to meet with the chapter and the candidate. (NOTE: Chapters can still simply skip asking for national endorsements, which I expect to be the case with NYC DSA / AOC)

- Labor remains a priority

- Labor remains a major focus of our organization, we passed CR10: DSA National Labor Commission Consensus Resolution: Building A Worker-Led Labor Movement (as amended by CR10-A02, CR10-A03, and CR10-A04).

- Housing & Tenant Organizing remains a priority

- We passed CR06: 2025 DSA Housing Justice Commission Consensus Resolution which states we will fight for the 4 Principles of Social Housing, and the core of our housing work will be building strong militant tenant unions

While a strong anti-Zionist resolution on Palestine had failed to win at the 2023 Convention, it is highly significant that at the 2025 Convention such a resolution won 56% of the votes, with 44% against. One point of contention involved new standards that candidates would be required to meet to be eligible for DSA endorsement: full and public support for the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement and for the Palestinian struggle. This would seem to preclude DSA’s support for many candidates that it has endorsed up until now, including Bernie Sanders. “However,” notes Stephan Kimmerle, “it will be up to the new NPC [National Political Committee] to interpret this resolution and the emphasis even of the people moving the resolution was that DSA would remain flexible in its implementation of that resolution.”

A decision that many of us regret involves the fate of an amendment to the international resolution that explicitly challenged “campist” perspectives, which was defeated — with 43% of the votes in favor and 56% against.

Attention was given to how DSA-endorsed candidates will campaign and perform their duties in office. The consensus resolution presented by DSA’s National Electoral Committee, and passed, focused on running candidates who represent DSA and come from the ranks of DSA, not simply giving endorsements to “progressive Democrats” seeking support. The resolution demanded that DSA endorsed candidates “openly and proudly identify with DSA and Socialism, including by: Expressly encouraging people to join DSA” and “identifying publicly as a ‘Socialist’ or ‘Democratic Socialist.’” It urges chapters to demand from candidates “a commitment to building a socialist slate and political independence.” It remains to be seen, of course, how this policy is actually applied.

Many resolutions — for which there was no time to discuss and vote on — ended up being referred to the National Political Committee (NPC), which oversees the functioning of the organization between it bi-annual conventions.

Elections to the NPC which took place at the convention are another indication of the leftward shift taking place in the organization. Of 24 slots on the NPC, only 9 went to caucus members in the moderate wing, while 18 went to those associated with the left — as it turned out, evenly divided with 9 positions won by caucuses in the far-left wing, and 9 won by caucuses of the Marxist center-left bloc.

It is important, however, to not make more of this than may be merited. “Our new NPC is ‘further left,’” commented one savvy delegate from Pittsburgh, “but it remains to be seen what that will mean.” This is related to the desire of many (though hardly all) activists in various caucuses to avoid splits and fissures that could result in a diminished DSA. At the same time, there is an extreme fluidity within some of the caucuses, and in our volatile times it is impossible to predict with any certainty how the internal situation will evolve.

In addition, there were discussions at the convention — not connected to resolutions or voting — that gave a vibrant sense of the political perspectives prevalent in DSA today. These included: 1) a remarkably radical speech by Rashida Tlaib and the convention’s response to it; 2) panel presentations by key organizers of Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral campaign in NYC; 3) a dynamic three-hour “First Ever Cross-Organizational Political Exchange” (two minutes per speaker) involving guests from a variety of movements and struggles interspersed with contributions of DSA members active in struggles. Eloquent and meaningful comments were offered by members of the Chicago Teachers Union, Caucus of Rank-and-file Electrical Workers (CREW), Essential Workers for Democracy, a rank-and-file caucus in the National Association of Letter Carriers, and Railroad Workers United, the Arise Chicago Workers Center, the Debt Collective, the Sunrise Movement, BDS and the Palestinian Youth Movement, both PSOL and the PT from Brazil, Belgium’s Workers Party), La France Insoumise, Morena from Mexico, Puerto Rico’s Democracia Socialista, and Japan’s Democratic Socialists.

The speech by Rashida Tlaib generated roars of approval and a standing ovation. Stephan Kimmerle aptly describes it:

Keynote speaker Congressmember Rashida Tlaib addressed the Convention with a powerful and emotional message against the war on Palestine. She linked the votes in Congress that fund the genocide with the lack of funding for reforms such as Medicare for All and clean water. Tlaib condemned “the establishment of both parties” for their role in financing the genocide, pointing out that both the Republicans and Democrats are funded by billionaires.

In a clear contrast and apparent criticism of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Tlaib stated, “A weapon is a weapon.” AOC had voted in July in favor of US funding Israel’s Iron Dome, justifying it by saying there is a difference between supplying “defensive weapons” and “offensive weapons” to Israel. In contrast, Tlaib and Ilhan Omar correctly voted against this. (AOC later voted against the military funding bill as a whole.)

Tlaib spoke out against “capitalistic systems of exploitation” and emphasized, “the working masses are hungry for revolutionary change… That is why DSA is so important. We are able to honestly and truthfully diagnose the problems facing working-class Americans.” She urged DSA — referring to the organization as “we” — to use language that is understandable to working-class people, those who corporate Democrats and Republicans have abandoned, in order to explain “what democratic socialism can mean for their lives.” Tlaib urged DSA to orient our work toward the broad mass of the working class and bring more people of color into our organization by convincing them of democratic socialist ideas — very necessary tasks for DSA.

Does it make sense for revolutionary Marxists to be part of DSA?

The reality of DSA — as reflected by the convention — was qualitatively different from my preconceived notions. It was much further to the Left than I expected, far more critical of, and inclined to reject, both capitalist parties. I was expecting something within which the kind of politics represented by DSA moderate wing dominated — with some opportunities for left-wing discussion, educational work, and involvement in some good and practical social action. The fact that this was the largest socialist organization in the United States and had grown dramatically, containing a very large number of young socialist-minded activists who were essentially part of our occupationally diverse working class — all of these were primary factors in my decision, over the past several years, to become involved in it.

The DSA that I have experienced in Pittsburgh over the past twelve months persuaded me that (1) it made sense for me to become seriously involved in this organization on the local level, and (2) that I must go to the national convention — as an observer — to get a more adequate sense of the organization as a whole. And this experience was a revelation for me. In this account I have tried to give some sense of what I found in the course of the organization’s national convention of August 8-10, 2025. I found a far more open, vibrant, leftwardly radicalizing reality than I had anticipated — replete with frustrating limitations and imperfections, but also open and evolving, with opportunities to help create a more effective socialist organization. There are also opportunities to learn much from the experience. DSA has great problems but enormous potential. So, yes, for me as a revolutionary Marxist, it certainly makes sense to be part of DSA. Not to “intervene” in DSA, but to be a genuine part of it.

It also makes sense to me to be part of Solidarity and of the Tempest Collective. Figuring out how these pieces fit together is a challenge to be dealt with through being actively involved in these organizations, while helping to build an effective movement for socialism.

DSA’s 2025 National Convention: A New Chapter Opens Up for the Socialist Movement

Friday 15 August 2025, by Philip Locker, Stephan Kimmerle

Last weekend over 1,200 elected delegates gathered at the biannual DSA national Convention. The Democratic Socialists of America’s highest decision-making body represented more than 80,000 members – up from 64,000 in October of last year. Delegates were optimistic about the potential to grow DSA in both numbers and influence, and to build toward a mass working-class party. [1]

The size, energy, and confidence at the Convention were all indications of a new chapter opening up for DSA and the socialist movement in the US. A wave of radicalization is bubbling up across the country. This reflects a growing resistance against Trump and the genocide in Palestine, along with a surge forward in socialist electoral campaigns highlighted by the Zohran Mamdani breakthrough. This was also visible at the Convention with a shift to the left in DSA’s positions and the election of a more left-wing national leadership.

Crucially, the left-wing of these emerging struggles are finding an organized expression in DSA. This shows the strength of DSA as a broad based democratic membership organization that fights for socialism in the electoral arena and through grassroots campaigning.

The potential clearly exists for DSA to develop into a much more visible socialist force, surpassing 100,000 members in the coming months, and beginning to sink real roots in the working class. However, this is not automatic. To seize this opportunity will require deliberate efforts not only to align with the sentiments of activists but also to help them turn towards winning over labor, social movements, and broader segments of the working class to break with the Democratic Party, fight for Palestinian liberation, and connect our movements to the struggle against capitalism and imperialism.

To advance along these lines, the new left-wing leadership of DSA will need to look to create unifying national campaigns and take conscious steps towards political independence from the Democrats while building a mass base of support for a working class political alternative. Another essential step will be organizing educational and broad-based discussions to develop a new political platform for DSA that can be a tool to popularize key fighting demands while helping to move the membership toward a more developed understanding of socialism as a break with capitalism.

At the same time the dynamics of the Convention and the preceding months also point to the dangers of DSA being more rooted in an online radical sub-culture rather than in working-class communities or the realities of mass struggle. The new left-wing DSA leadership is at risk of bending DSA’s politics and profile to reflect the outlook and pressures of radical activists who often lack the necessary politics and orientation to successfully carry out mass work within the working class.

Unfortunately the convention agenda seemed to be stuck in a business-as-usual routine. Rather than a focus on the biggest issues and debates facing DSA and the working class, the resolutions and amendments on the agenda, especially on the first day, concentrated on the nitty-gritty aspects of DSA’s internal organizing and structures. There was also a notable lack of discussions on climate change, socialist feminism, and relatively limited exchange on strategies for fighting racism (beyond the issue of immigration).

Rashida Tlaib: “A Weapon Is a Weapon”

Palestine was the most dominant topic at the Convention.

Keynote speaker Congressmember Rashida Tlaib addressed the Convention with a powerful and emotional speech that highlighted the war on Palestine. She linked the votes in Congress that fund the genocide with the lack of funding for reforms such as Medicare for All and clean water. Tlaib condemned “the establishment of both parties” for their role in financing the genocide, pointing out that both the Republicans and Democrats are funded by billionaires.

In a clear contrast and apparent criticism of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC), Tlaib stated, “A weapon is a weapon.” AOC had voted in July in favor of US funding for Israel’s Iron Dome, justifying it by saying there is a difference between supplying “defensive weapons” and “offensive weapons” to Israel. In contrast, Tlaib and Ilhan Omar correctly voted against this. (AOC later voted against the military funding bill as a whole.)

Tlaib spoke out against “capitalistic systems of exploitation” and emphasized, “the working masses are hungry for revolutionary change… That’s why DSA is so important. We are able to honestly and truthfully diagnose the problems facing working-class Americans.” She urged DSA – referring to the organization as “we” – to use language that is understandable to working-class people, those who corporate Democrats and Republicans have abandoned, in order to explain “what democratic socialism can mean for their lives.” Tlaib urged DSA to orient our work toward the broad mass of the working class and bring more people of color into our organization by convincing them of democratic socialist ideas – very necessary tasks for DSA.

In an otherwise internally focused Convention with many bureaucratic-sounding resolutions and amendments, Tlaib’s comments inspired the delegates who roared with huge applause and loud chants of “Free Palestine!”

While Tlaib’s sharp criticism of corporate Democrats was very welcome, her votes to elect Hakeem Jeffries as leader of the House Democrats are not consistent with this message. Tlaib’s outstanding role in the opposition to the slaughter in Gaza unfortunately stands in contrast to her votes to expand NATO and fund the US involvement in the war in Ukraine.

Tlaib’s speech highlighted the role of Democratic Socialists as crucial in the struggle for a better world. This excellent point needs to be matched by her and other DSA candidates running for office with a prominent socialist profile and by actively using their campaigns to promote DSA and build independent political organizations of working people.

Internationalism

A big part of the discussion on Palestine was the deliberations on an anti-Zionist resolution (R22). This was a continuation of discussions at the 2023 Convention where a similar resolution had been narrowly defeated. This time the Convention passed the resolution, mandating that candidates are ineligible for an DSA endorsement – both nationally and locally – if they fail to meet certain standards for supporting BDS and the Palestinian struggle and establishes that DSA members can be expelled for certain actions or beliefs contrary to DSA’s positions on Palestine.

This would not have allowed DSA to endorse Bernie Sanders – and with that build an organization clearly criticizing Sanders for his short-comings on the question of Zionism. It will, if applied, not allow DSA to critically endorse for example a candidacy of left-wing UAW leader Shawn Fein for president in 2028, as he is almost as weak on international questions (as can been seen with his position on tariffs) as Bernie Sanders. This will not strengthen but weaken the anti-Zionist and socialist impact of DSA on the left-wing moving base of such politicians.

However, it will be up to the new National Political Committee (NPC, the national leadership elected by the Convention) to interpret this resolution and the emphasis even of the people moving the resolution was that DSA would remain flexible in its implementation.

An amendment to this resolution, which aimed to remove language about the expulsion of members who act in support of Zionism and automatic exclusion of endorsements of candidates failing to meet the defined standards, was unsuccessful but still garnered 46% support.

The unamended resolution passed with 56% to 44%.

The ongoing debate in DSA between supporters of a “campist” position and an anti-campist internationalism was expressed around an amendment to the International Committee’s consensus resolution (CR02-A02). “Campism” is the view that the enemies of Western imperialism are our allies, regardless of their politics or how they treat “their own” working class.

The summary of the anti-campist amendment read:

DSA should build relationships with a diverse array of left parties and movements in other countries, including those in and out of government. DSA should learn from and stand in solidarity with movements in the Global South fighting for democracy and socialism against all governments that engage in the repression of democratic rights and side with capital over workers. Finally, DSA should re-affirm that the NPC is the highest decision-making body of the organization between Conventions.

The clarification about the NPC being the highest decision-making body was added given previous conflicts between the elected leadership of DSA (the NPC) and the leadership of the International Committee. This amendment failed with 43% for and 56% against it.

Electoral Work

The motto of the Convention was “Rebirth and Beyond: Reflecting on a decade of DSA’s growth and preparing for a decade of party building.” However, the road ahead – how to build toward a mass workers’ party – is highly contested.

The Convention’s focus was less on the party question itself and more on how DSA-endorsed candidates will campaign and perform their duties in office. Given the frustration of many DSA members about the moderation of many DSA endorsed elected officials, this year’s consensus resolution presented by the National Electoral Committee focused on running candidates who represent DSA and come from the ranks of DSA. The Convention voted in favor of this resolution, demanding that endorsed candidates “openly and proudly identify with DSA and Socialism, including by: Expressly encouraging people to join DSA” and “identifying publicly as a ‘Socialist’ or ‘Democratic Socialist.’” It urges chapters to demand from candidates to show “a commitment to building a socialist slate and political independence.”

The wish to move away from endorsements that leave us without much influence on elected officials also was reflected in the resolution arguing against “paper endorsements” in general. The resolution also conflates endorsing non-DSA candidates with “paper endorsements.”

While the resolution correctly takes steps to build our strength to run politically stronger DSA candidates, the opposition to “paper endorsements” threatens to cut DSA off from engaging in campaigns where socialists can benefit by aligning themselves with radical left-wing candidates who are not part of DSA. DSA’s endorsement of Bernie Sanders for president in 2020 was the largest campaign in DSA history (far from a “paper endorsement”) yet Sanders was not a DSA member and did not represent the politics of DSA. DSA was absolutely correct to endorse Sanders, despite his political weaknesses, as his campaigns represented on the whole a major step forward and an opportunity to build support for socialism. DSA’s mistake was how it uncritically supported Sanders and failed to openly and clearly challenge his political weaknesses, not that it endorsed and helped to build the campaign.

Some movers of the motion still claimed that DSA would retain its flexibility to endorse such candidates.

With the 2028 presidential election coming up and the call by the UAW and other unions for a mass strike on May 1, 2028, an important resolution debated at the Convention was Resolution 33, which stated:

DSA should aspire to build a broad left-labor coalition, composed of labor unions and other mass organizations, which can draft a platform; recruit candidates for federal, state, and local office for the 2026 and 2028 elections; and draft a socialist candidate for the 2028 presidential election. In order to gain real traction and look more like Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaigns than past third-party campaigns, DSA should back a viable candidate in the Democratic presidential primary, such as a nationally known elected official, labor leader, or public figure, who will primarily publicly identify with and promote DSA, socialism, and/or a left-labor coalition rather than the Democratic Party. DSA will advocate for such a coalition to endorse independent and nonpartisan down-ballot candidates as well as candidates running in Democratic primaries.

It passed by 59% to 41%.

Labor

Despite the importance of DSA’s work in labor, there was limited discussion on this topic. An amendment (CR10-A01) to the main resolution on labor presented by the National Labor Commission (CR10), aimed to clarify the political role of socialists in the labor movement, directing the National Labor Commission to “lead and coordinate DSA members in the labor movement to organize against the Democratic Party, against the Republican Party and the authoritarian right wing, and for socialist politics.” This amendment also aimed to raise the bar for democratic bargaining processes from just demanding a “right of members to vote on all collective bargaining agreements” to the “right of members to have democratic control of collective bargaining and the strategy around it.” The amendment lost narrowly with 48% in favor, 52% against.

One Member, One Vote?

The Groundwork caucus proposed a resolution (CB02) to elect the national leadership through an online vote by all members, a position supported by the Socialist Majority Caucus. The proposal sparked a lot of debate leading up to the Convention. While it was presented as a means to enhance democracy, opponents argued that it would result in less deliberation among elected delegates, who come together to debate, persuade comrades of their positions, and facilitate a more informed decision-making process.

Behind the technicalities of this question – of which system would be better for making decisions – lies the unacknowledged reality that the activists (and therefore the delegates) in DSA are clearly to the left of the vast majority of members. Groundwork and Socialist Majority, the two moderate caucuses supporting “1M1V,” aimed to leverage this to push the organization, relatively speaking, to the right. Unfortunately, the left did not use their majority on the NPC for the last two years to take significant initiatives to activate and educate the broad membership (through dynamic campaigns and meaningful debate that engages the broad membership on key questions).

1M1V was rejected by 60% (736 votes) of the delegates, while 40% (487) voted for it.

Leadership Elections

DSA is a big tent, multi-tendency organization which has a lively internal culture with a wide range of political caucuses. Broadly speaking DSA is divided into three wings:

1. A moderate wing that emphasizes mass work, aims for DSA to connect with a broader working-class audience, and adopts an opportunistic approach toward DSA’s elected officials, the Democratic Party (accepting a dirty stay), and labor leaders. This includes Groundwork and Socialist Majority Caucus (SMC).

2. A far-left wing that reflects the sentiments of left activists within the Palestine movement and advocates for a campist “anti-imperialism,” willing to align even with ultra-religious and conservative forces like Hamas and the Houthis as long as they are opposing the US empire. This includes Red Star and Springs of Revolution. (The danger of self-marginalizing approaches of the far-left were visible in the last term of the NPC, especially on international questions.) [2]

3. A Marxist center that seeks to merge an orientation towards the mass of working-class people with a strategy aimed at building an independent socialist party, while promoting class struggle and socialist politics within labor and social movements. This includes Bread & Roses.

Examining these categories, Marxist Unity Group (MUG) has frequently aligned with Red Star over the past two years. The majority of Reform & Revolution (R&R) has also shifted over the past two years more in that direction and away from the earlier politics of the caucus (although R&R also broke with others on the left on certain Convention votes). In the lead-up to the Convention, R&R expressed a reluctance to collaborate with the moderate forces within DSA, which could present significant challenges for the future of the organization.

Conversely, MUG and R&R have also been emphasizing, at least in rhetoric, the importance of principled socialist mass work. If this approach from MUG and R&R prevails, we could see:

• A more engaging and dynamic leadership within DSA, moving toward holding elected officials accountable through robust public engagement that seeks to educate DSA members and the left-wing base of electeds about the need for principled socialist politics.

• Significant progress toward DSA functioning like a party, promoting the need for a mass workers party, and actively working to lay the basis for a break with the Democratic Party (what is known in DSA as a “dirty break”).

• A revival of a more vigorous rank-and-file strategy focused on building labor from the bottom up, employing a class-struggle approach, and engaging in union reform caucuses with a socialist strategy.

• National outward facing campaigns by DSA that honor the big-tent nature of the organization while uniting activists in a collective effort to fight for our shared goals.

• An inclusive process to develop a new program for DSA that facilitates a full and democratic discussion on key issues, such as our stance toward the capitalist state (e.g., how should Mayor Mamdani interact with the police? How does this align with our overarching goals?).

The Convention saw a shift away from the moderate wing and towards the left-wing. The elections of the co-chairs saw the two previous chairs re-elected. Megan Romer from the Red Star caucus (part of the far-left wing) came in first with 483 votes. She was followed closely by Ashik Siddique from Groundwork caucus (part of the moderate wing), with 458 votes. Alex Pellitteri of the Bread & Roses caucus came third (295 votes), thereby failing to win a co-chair position.

The political composition of the newly elected NPC shifted to the left. In a simplified presentation, the main groupings on the new NPC are:

• 10 moderate members (four from SMC, five from Groundwork, and one from Carnation),

• Eight from the center (three from B&R, two from R&R, and three from MUG), and

• Nine from its far-left wing (one independent politically sympathetic to Red Star, three from Red Star, four from SoR, and one from the Libertarian Socialist Caucus)

On the 2023-25 NPC, Bread & Roses members were the swing vote between the moderate and left wings. With the shift to the left on the new NPC it appears that the Reform & Revolution NPC members may now find themselves in that role.

The challenge for revolutionary Marxists is to build a Marxist center of DSA that can lead in the direction of principled mass work and national visibility of DSA in broader movements against Trump, in labor, and in social movements. Comrades in B&R, MUG, and R&R should urge their three caucuses to politically lead this fight, charting a path independent of opportunism and sectarianism.

14 August 2025

If you like this article or have found it useful, please consider donating towards the work of International Viewpoint. Simply follow this link: Donate then enter an amount of your choice. One-off donations are very welcome. But regular donations by standing order are also vital to our continuing functioning. See the last paragraph of this article for our bank account details and take out a standing order. Thanks.

Attached documents

dsa-s-2025-national-convention-a-new-chapter-opens-up-for_a9126-2.pdf (PDF - 935.8 KiB)

Extraction PDF [->article9126]

dsa-s-2025-national-convention-a-new-chapter-opens-up-for_a9126-3.pdf (PDF - 938.6 KiB)

Extraction PDF [->article9126]

dsa-s-2025-national-convention-a-new-chapter-opens-up-for_a9126.pdf (PDF - 938.6 KiB)

Extraction PDF [->article9126]

Footnotes

[1] We are publishing the following report on the recent DSA convention for informational purposes. Signed articles do not indicate International Viewpoint’s endorsement of the political positions expressed.

[2] The new book, A User’s Guide to DSA, gives a relevant example. The new DSA Maoist caucus, Liberation, “controversially signed on to a statement in support of a left-wing activist who carried out a terrorist shooting of two Israeli embassy staffers in protest against the war on Gaza. This was quickly taken up by opponents of DSA, including Andrew Cuomo (former New York governor and the main establishment-backed candidate for New York City mayor in the 2025 Democratic Party primary), which led to the NPC publicly stating that DSA opposes vigilante violence and condemns the shooting of the two Israeli embassy staffers. This statement was opposed by Red Star and MUG NPC members, representing the views of the far-left in DSA. Red Star and MUG members argued that while they were against vigilante violence they thought a public position from DSA would further fuel the right-wing frenzy and therefore it was best to say nothing.” (page 23).

Learning from the DSA convention

Stephan Kimmerle is a an activist in the Reform and Revolution caucus.

Philip Locker

Philip Locker is an activist in the Reform and Revolution caucus.

International Viewpoint is published under the responsibility of the Bureau of the Fourth International. Signed articles do not necessarily reflect editorial policy. Articles can be reprinted with acknowledgement, and a live link if possible.

No comments:

Post a Comment