Idaho is top pick for Energy Department nuclear test reactor

by Keith Ridler

The U.S. government said Thursday that Idaho is its preferred choice ahead of Tennessee for a test reactor to be built as part of an effort to revamp the nation's fading nuclear power industry by developing safer fuel and power plants.

The U.S. Department of Energy said in an email to The Associated Press that the site that includes Idaho National Laboratory will be listed as its preferred alternative in a draft environmental impact statement planned for release in December.

The Versatile Test Reactor, or VTR, would be the first new test reactor built in the U.S. in decades and give the nation a dedicated "fast-neutron-spectrum" testing capability. Some scientists decry the plan, saying fast reactors are less safe than current reactors.

A news release by the Energy Department earlier Thursday listed both Idaho and Tennessee as possible locations without selecting one as being favored.

However, Republican U.S. Sen. Jim Risch of Idaho shared a tweet by the Energy Department's Office of Nuclear Energy identifying Idaho as its top choice for the reactor.

"Having the VTR at (the Idaho National Laboratory) will allow American companies to perform nuclear testing here in the U.S.—another step toward energy independence," Risch commented with his retweet.

The Energy Department, after some initial confusion when contacted by the AP, confirmed Idaho was its preferred choice for the project.

The test reactor, if it advances and Idaho remains the top choice, would be built at the department's 890-square-mile (2305-square-kilometer) site in eastern Idaho that includes a nuclear research lab.

"The Versatile Test Reactor continues to be a high-priority project for DOE to ensure nuclear energy plays a role in our country's energy portfolio," Secretary of Energy Dan Brouillette said. "Examination of the environmental impacts reflects DOE's commitment to clean energy sources and will serve as an example for others looking to deploy advanced reactor technologies."

The final environmental impact statement is due in 2021, followed by what's called a record of decision finalizing the selection of the site. Plans call for building the reactor by the end of 2025.

The Department of Energy's draft environmental impact statement also examines building the test reactor at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee as an alternative.

The department had a fast reactor, the Experimental Breeder Reactor II, operating in eastern Idaho until it was shut down in 1994 as the nation turned away from nuclear power.

Most nuclear reactors in use now are "light-water" reactors fueled by uranium and cooled with water.

Some scientists are wary of fast reactors, noting they're cooled with harder to control liquid sodium and likely fueled by plutonium, increasing potential nuclear terrorism risks because plutonium can be used to make nuclear weapons.

Revamping the nation's nuclear power is part of a strategy to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by generating carbon-free electricity with nuclear power initiated under the Obama administration and continuing under the Trump administration, despite Trump's downplaying of global warming.

Explore further Energy Department wants to build nuclear test 'fast' reactor

© 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Tuesday, November 24, 2020

Invention lets rotting veggies make a greener world

by Peter Grad , Tech Xplore

Credit: James Dyson Award

For generations, kids have been coaxed into finishing their vegetables after their parents sternly advised them that it is not nice to waste food when people are starving elsewhere in the world. But someday soon, kids may have a comeback: "If we eat those vegetables, we can't help fight climate change, reduce the carbon footprint or help provide power to underserved regions of our world."

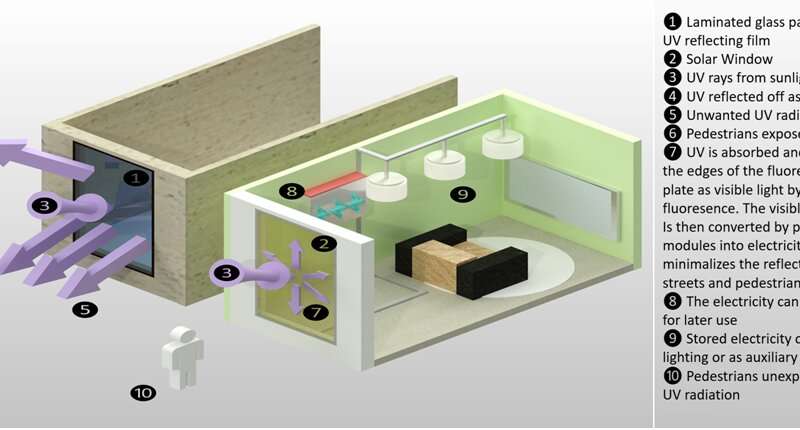

Those kids—and the rest of us—will have Carvey Ehren Maigue to thank. The engineering student has designed a material composed of fruit and vegetables that collects light and converts it into electricity. Where it differs from solar panels, which trap mainly visible and infrared light, is that it utilizes ultraviolet waves.

The 27-year-old student at the Philippines Mapua University in Manila extracted organic luminescent compounds from rotting fruits and vegetables and suspended them in a resin compound. Ultraviolet light passing thought the resin is converted into visible light. And unlike solar panels, Maigue's device, called Aureus, does not need to face the sun since it can effectively use ultraviolet light that is dispersed and scattered off of surfaces.

Aureus uses solar panels to convert the visible light it generates into electricity.

For generations, kids have been coaxed into finishing their vegetables after their parents sternly advised them that it is not nice to waste food when people are starving elsewhere in the world. But someday soon, kids may have a comeback: "If we eat those vegetables, we can't help fight climate change, reduce the carbon footprint or help provide power to underserved regions of our world."

Those kids—and the rest of us—will have Carvey Ehren Maigue to thank. The engineering student has designed a material composed of fruit and vegetables that collects light and converts it into electricity. Where it differs from solar panels, which trap mainly visible and infrared light, is that it utilizes ultraviolet waves.

The 27-year-old student at the Philippines Mapua University in Manila extracted organic luminescent compounds from rotting fruits and vegetables and suspended them in a resin compound. Ultraviolet light passing thought the resin is converted into visible light. And unlike solar panels, Maigue's device, called Aureus, does not need to face the sun since it can effectively use ultraviolet light that is dispersed and scattered off of surfaces.

Aureus uses solar panels to convert the visible light it generates into electricity.

Maigue's creation was the winning entry in this year's James Dyson Award in the category of sustainability. The Dyson award was established by inventor James Dyson, a billionaire and Britain's richest man, and is open to college students worldwide. Some 1,800 entries were submitted in the category this year.

"We need to utilize our resources more and create systems that don't deplete our current resources," Maigue said. "With Aureus, we upcycle the crops of the farmers that were hit by natural disasters such as typhoons, which also happen to be an effect of climate change. By doing this, we can be both future-looking and solve problems that we are currently experiencing now."

He noted that the principles behind Aureus are the same as those behind the aurora borealis, more commonly known as the Northern lights (or Southern lights if you are in Australia). Charged atomic particles emitted by the sun entering the Earth's atmosphere interact with other atoms and release photons, or particles of light. Brightly colored neon lights also demonstrate the same principle.

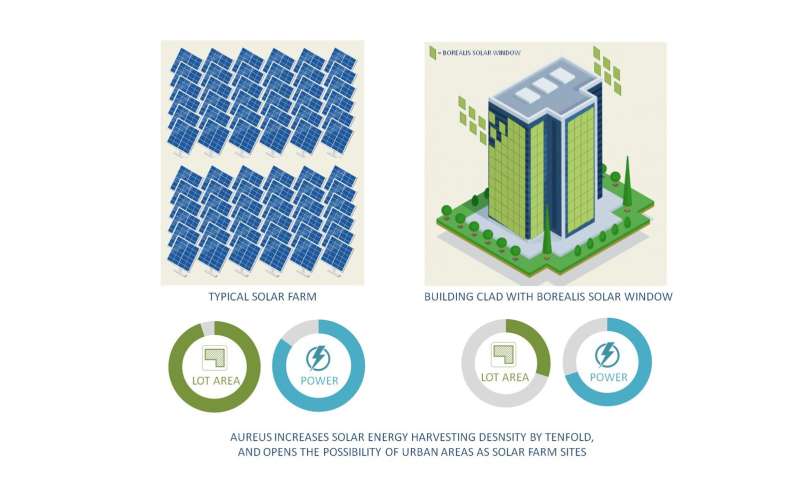

Aureus would be applied to skyscraper windows to essentially create vertical solar energy farms. Maigue explained that modern buildings use window coatings that deflect ultraviolet light and often redirect it towards passersby below. Aureus could capture that light and put it to good use.

"I want to create a better form of renewable energy that uses the world's natural resources, is close to people's lives, forging achievable paths and rallying towards a sustainable and regenerative future," Maigue said.

Credit: James Dyson Award

Aureus is not yet ready for mass production. Maigue said he is undertaking further research in efforts to boost the useful portion of useful luminescent particles derived from fruits and vegetables from 80 percent to 100 percent.

So for now, traditional solar panels and windows will lead the growing movement toward renewable energy resources. And kids will still have to finish their vegetables.

Explore further Sunny prospects for start-up's clear solar energy windows

Aureus is not yet ready for mass production. Maigue said he is undertaking further research in efforts to boost the useful portion of useful luminescent particles derived from fruits and vegetables from 80 percent to 100 percent.

So for now, traditional solar panels and windows will lead the growing movement toward renewable energy resources. And kids will still have to finish their vegetables.

Explore further Sunny prospects for start-up's clear solar energy windows

More information: www.jamesdysonaward.org/en-US/ … gy-uv-sequestration/

© 2020 Science X Network

The motivation for sustainable aviation fuels

by Susan Bauer, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

More information: Sustainable Aviation Fuel: Review of Technical Pathways Report. www.energy.gov/eere/bioenergy/ … ical-pathways-report

Provided by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

by Susan Bauer, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

PNNL developed a proprietary catalyst to convert ethanol, produced from waste carbon, to a jet fuel approved for use in commercial aviation.

Credit: Andrea Starr | Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Global air travel consumes more than 100 billion gallons of jet fuel annually. That's expected to more than double by 2025 to 230 billion gallons. Despite the current pandemic, these projections reflect future anticipated passenger demand. Airlines want to meet market demands while simultaneously reducing their carbon emissions.

In fact, airlines around the world have committed to carbon-neutral growth beginning in 2021. As part of that commitment, U.S. airlines have set a goal to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 50 percent by 2050 compared to 2005 levels.

Reaching that goal will not be easy. Electric planes won't make much of a dent because the batteries can only power the smallest of light planes. The only way to achieve emission reduction goals is with liquid fuels that have a lower carbon footprint: Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF).

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory's John Holladay co-authored a recent report that presents a pathway to low-cost, clean-burning, and low-soot-producing jet fuel.

"Today, there are seven approved SAF pathways, but their use is limited. Airlines really want to use SAF but it needs to be cost-competitive with petroleum-based fuels, since fuel makes up about 30 percent of the operating cost of an airline," said Holladay, the transportation sector manager at PNNL who helped develop a waste-carbon-based fuel used in a Virgin Atlantic flight.

The report, Sustainable Aviation Fuel: Review of Technical Pathways, was authored by PNNL, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, and University of Dayton for the Bioenergy Technologies Office (BETO) in the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. It outlines research needs for producing more jet fuel from renewable and wasted resources.

The report presents new insights resulting from a study of the aviation industry, commercial jet fuel, its composition, specifications and certification process, and the challenges and successes with approved chemical pathways that convert biomass to jet fuel. The report also assesses process improvements, technoeconomic analysis, and supply chain issues.

Solving another problem

============================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================

As detailed in the report, the cost of sustainable raw materials can likely be reduced by looking at non-traditional biomass. The classic idea of corn or specific crops grown to produce fuels is giving way to using non-traditional waste materials. Environmental problems like municipal solid waste, sewage, waste gasses like carbon monoxide, and even deconstructed plastics are rich sources of carbon that can be converted into jet fuel.

Fats and agricultural waste or forest residues are other types of discarded material, which can be treated with existing biological or thermal processes to produce high-quality intermediates.

"It costs cities and companies money to manage and treat these wastes, but when we can convert these liabilities into a high-value product, the value proposition changes altogether," said Holladay. "When we include these low-cost feedstocks, there becomes enough biomass to scale to industrial levels of production. Some feedstocks are even free, and that reduces the cost of SAF significantly."

Optimizing jet fuel properties

In the near-term, expanding production capacity of existing approved fuels is critical. But eventually, providing a fuel that has improved properties, within the bounds of specifications, further improves the possibility for market pull, according to the report.

"We don't have to just mimic petroleum-based fuel," said Holladay. "If we're going to make a new fuel, we might as well make a fuel that's better. And with the additional research and development suggested in this report, we can."

The report calls for a deeper understanding of the critical fuel properties of the four hydrocarbon families that make up jet fuel. These families are described in chemical terms as aromatics, n-alkanes, iso-alkanes, and cycloalkanes. The latter two families of molecules provide all the properties needed in jet fuel. The first two, aromatics and n-alkanes will often be coproduced; however, their primary production is not an optimal research area for SAF.

SAF must first and foremost must be safe for use in air travel. This includes producing a clean fuel that doesn't harm the jet engines, that doesn't freeze at high altitudes, and has a low flashpoint for safely refueling on the ground. With safety in mind, there are new opportunities for reducing soot formation by reducing the amount of aromatics in the fuel.

"In the end, we need SAF that are safe, inexpensive, and have high energy content," said Holladay." The report recommends that research focus on ways to make low-cost iso-alkanes and cycloalkanes that can enable better SAF performance."

Blending the two can give fuel higher energy content than jet fuel while meeting the density specification required, so planes can fly farther on less fuel. They also can burn cleaner by diluting the aromatics in fuel. Aromatics create soot and the tell-tale contrails that contribute to atmospheric warming.

There are many types of iso-alkanes and cycoalkanes that could be used in jet fuel, but they are expensive and some cycloalkanes may freeze in extreme cold temperatures experienced at cruising altitudes. Recommended research goals include better understanding combustion and molecular properties of cycloalkanes and how they could be produced inexpensively and approved for use in jet fuel.

It's the fuel… and a lot more

The report also notes the critical fuel properties required for certification processes. Jet fuel certification is time consuming and expensive and can only be accomplished by understanding the critical fuel properties required and their impact.

The authors also note that biorefineries, which will convert low-cost biomass and wastes, must be versatile and produce a variety of jet and other fuels. Technology must enable these refineries to be cost- competitive when operated at a much smaller scale than petroleum refineries. Supply chains—from feedstocks and infrastructure to storage and delivery—must also be accounted for when considering the full cost of the fuel. Those topics need to be addressed in research and in analysis of technical and economic benefits to the SAF industry.

The report encourages U.S. researchers to engage with partners in Canada and Mexico to take advantage of synergies across North America. Canada is home to a third of the world's certified sustainable forests, and Mexico has a warm climate that facilitates growth of sustainable feedstocks. Both countries can contribute to biomass feedstocks and offer unique opportunities for collaboration.

Explore furtherMicrosoft, Alaska Airlines team up for alternative jet fuel

Global air travel consumes more than 100 billion gallons of jet fuel annually. That's expected to more than double by 2025 to 230 billion gallons. Despite the current pandemic, these projections reflect future anticipated passenger demand. Airlines want to meet market demands while simultaneously reducing their carbon emissions.

In fact, airlines around the world have committed to carbon-neutral growth beginning in 2021. As part of that commitment, U.S. airlines have set a goal to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 50 percent by 2050 compared to 2005 levels.

Reaching that goal will not be easy. Electric planes won't make much of a dent because the batteries can only power the smallest of light planes. The only way to achieve emission reduction goals is with liquid fuels that have a lower carbon footprint: Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF).

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory's John Holladay co-authored a recent report that presents a pathway to low-cost, clean-burning, and low-soot-producing jet fuel.

"Today, there are seven approved SAF pathways, but their use is limited. Airlines really want to use SAF but it needs to be cost-competitive with petroleum-based fuels, since fuel makes up about 30 percent of the operating cost of an airline," said Holladay, the transportation sector manager at PNNL who helped develop a waste-carbon-based fuel used in a Virgin Atlantic flight.

The report, Sustainable Aviation Fuel: Review of Technical Pathways, was authored by PNNL, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, and University of Dayton for the Bioenergy Technologies Office (BETO) in the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. It outlines research needs for producing more jet fuel from renewable and wasted resources.

The report presents new insights resulting from a study of the aviation industry, commercial jet fuel, its composition, specifications and certification process, and the challenges and successes with approved chemical pathways that convert biomass to jet fuel. The report also assesses process improvements, technoeconomic analysis, and supply chain issues.

Solving another problem

============================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================

As detailed in the report, the cost of sustainable raw materials can likely be reduced by looking at non-traditional biomass. The classic idea of corn or specific crops grown to produce fuels is giving way to using non-traditional waste materials. Environmental problems like municipal solid waste, sewage, waste gasses like carbon monoxide, and even deconstructed plastics are rich sources of carbon that can be converted into jet fuel.

Fats and agricultural waste or forest residues are other types of discarded material, which can be treated with existing biological or thermal processes to produce high-quality intermediates.

"It costs cities and companies money to manage and treat these wastes, but when we can convert these liabilities into a high-value product, the value proposition changes altogether," said Holladay. "When we include these low-cost feedstocks, there becomes enough biomass to scale to industrial levels of production. Some feedstocks are even free, and that reduces the cost of SAF significantly."

Optimizing jet fuel properties

In the near-term, expanding production capacity of existing approved fuels is critical. But eventually, providing a fuel that has improved properties, within the bounds of specifications, further improves the possibility for market pull, according to the report.

"We don't have to just mimic petroleum-based fuel," said Holladay. "If we're going to make a new fuel, we might as well make a fuel that's better. And with the additional research and development suggested in this report, we can."

The report calls for a deeper understanding of the critical fuel properties of the four hydrocarbon families that make up jet fuel. These families are described in chemical terms as aromatics, n-alkanes, iso-alkanes, and cycloalkanes. The latter two families of molecules provide all the properties needed in jet fuel. The first two, aromatics and n-alkanes will often be coproduced; however, their primary production is not an optimal research area for SAF.

SAF must first and foremost must be safe for use in air travel. This includes producing a clean fuel that doesn't harm the jet engines, that doesn't freeze at high altitudes, and has a low flashpoint for safely refueling on the ground. With safety in mind, there are new opportunities for reducing soot formation by reducing the amount of aromatics in the fuel.

"In the end, we need SAF that are safe, inexpensive, and have high energy content," said Holladay." The report recommends that research focus on ways to make low-cost iso-alkanes and cycloalkanes that can enable better SAF performance."

Blending the two can give fuel higher energy content than jet fuel while meeting the density specification required, so planes can fly farther on less fuel. They also can burn cleaner by diluting the aromatics in fuel. Aromatics create soot and the tell-tale contrails that contribute to atmospheric warming.

There are many types of iso-alkanes and cycoalkanes that could be used in jet fuel, but they are expensive and some cycloalkanes may freeze in extreme cold temperatures experienced at cruising altitudes. Recommended research goals include better understanding combustion and molecular properties of cycloalkanes and how they could be produced inexpensively and approved for use in jet fuel.

It's the fuel… and a lot more

The report also notes the critical fuel properties required for certification processes. Jet fuel certification is time consuming and expensive and can only be accomplished by understanding the critical fuel properties required and their impact.

The authors also note that biorefineries, which will convert low-cost biomass and wastes, must be versatile and produce a variety of jet and other fuels. Technology must enable these refineries to be cost- competitive when operated at a much smaller scale than petroleum refineries. Supply chains—from feedstocks and infrastructure to storage and delivery—must also be accounted for when considering the full cost of the fuel. Those topics need to be addressed in research and in analysis of technical and economic benefits to the SAF industry.

The report encourages U.S. researchers to engage with partners in Canada and Mexico to take advantage of synergies across North America. Canada is home to a third of the world's certified sustainable forests, and Mexico has a warm climate that facilitates growth of sustainable feedstocks. Both countries can contribute to biomass feedstocks and offer unique opportunities for collaboration.

Explore furtherMicrosoft, Alaska Airlines team up for alternative jet fuel

More information: Sustainable Aviation Fuel: Review of Technical Pathways Report. www.energy.gov/eere/bioenergy/ … ical-pathways-report

Provided by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Researchers develop more efficient method to recover heavy oil

by Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology

More information: Yuichiro Nagatsu et al, Chemical Flooding for Enhanced Heavy Oil Recovery via Chemical-Reaction-Producing Viscoelastic Material, Energy & Fuels (2020).

Provided by Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology

by Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology

Novel chemical flooding method. Credit: Yuichiro Nagatsu/ TUAT

The current global supply of crude oil is expected to meet demand through 2050, but there may be a few more drops to squeeze out. By making use of a previously undesired side effect in oil recovery, researchers have developed a method that yields up to 20% more heavy oil than traditional methods.

Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (TUAT) team published their results on August 24 in Energy & Fuels, a journal of the American Chemical Society.

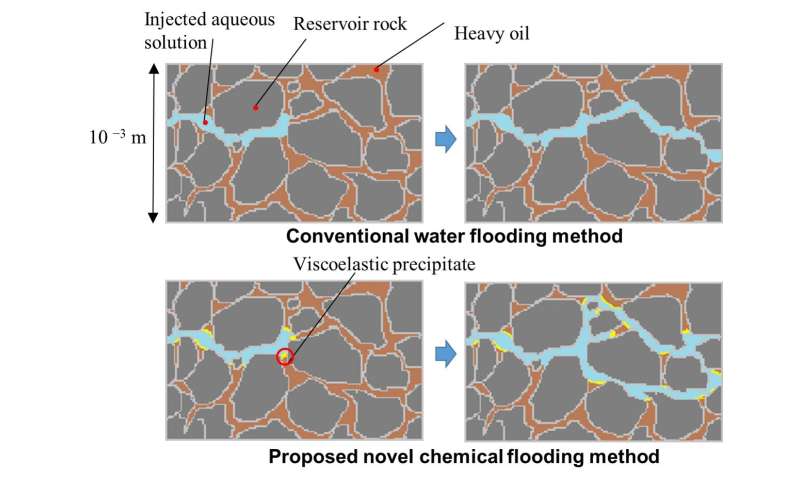

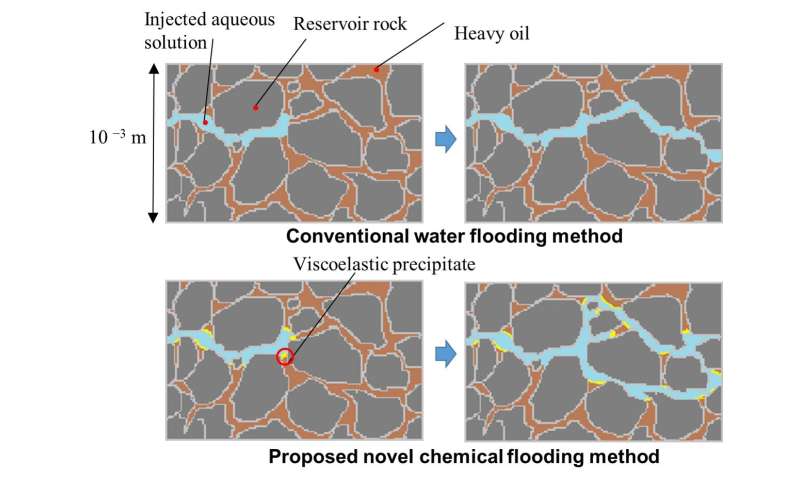

The researchers focused on heavy oil recovery, which involves extracting highly viscous oil stuck in porous rocks.

"The total estimated volume of recoverable heavy oil is almost the same as the remaining light reserves in the world," said paper author Yuichiro Nagatsu, associate professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering at TUAT. "With the depletion of light oil resources and rising energy demands, the successful recovery of heavy oil is becoming increasingly important."

Generally, less than 10% of heavy oil may be produced from the reservoirs by natural flow after drilling the well. To yield more oil, water may be injected into the reservoir to maintain pressure in order to keep the flow moving. Engineers may also make the water more alkaline by adding sodium hydroxide or sodium carbonate to help the oil flow better. Called chemical flooding, this process often fails to yield much heavy oil, as it is too thick for even the enriched water to sweep up. Heavy oil can also be made to flow more easily through heat, but that's not a tangible solution for deep or thin reservoirs, according to Nagatsu.

"It is important to develop non-thermal chemical flooding for the recovery of heavy oil," Nagatsu said. "The key problem of chemical flooding in heavy oil reservoirs is an inefficient sweep as a result of the low mobility of the oil."

Because the viscosity of water and heavy oil differ so greatly, Nagatsu said, contemporary sweep methods are inefficient for heavy oil recovery.

To correct this inefficiency in chemical recovery, Nagatsu and his team injected calcium hydroxide into their model reservoir. The compound helps oil to flow more smoothly but is considered undesirable because it reacts with the oil to produce a metallic soap where the water and oil interface.

"The metallic soap behaves as a viscoelastic material in the pore and blocks the preferentially swept region and improves the sweep efficiency," Nagatsu said.

The metallic soap stops the sweeping flow from moving into already swept areas, forcing the forward recovery of heavy oils locked deep in rocks and crevices. In experimental testing, the method yielded 55% of oil in the reservoir, compared to a 35% recovery using alkaline water and a 33% recovery using regular water. Nagatsu noted that this method is inexpensive, can be used in a range of temperatures and it does not require energy-consuming techniques to perform.

The researchers plan to study the effectiveness of this method across crude oil viscosity ranges and in different ranges of oil reservoir permeability in laboratory experiments before moving to field tests. They would also like to engage with industry to further develop the technology for practical application, Nagatsu said.

Explore further

The current global supply of crude oil is expected to meet demand through 2050, but there may be a few more drops to squeeze out. By making use of a previously undesired side effect in oil recovery, researchers have developed a method that yields up to 20% more heavy oil than traditional methods.

Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (TUAT) team published their results on August 24 in Energy & Fuels, a journal of the American Chemical Society.

The researchers focused on heavy oil recovery, which involves extracting highly viscous oil stuck in porous rocks.

"The total estimated volume of recoverable heavy oil is almost the same as the remaining light reserves in the world," said paper author Yuichiro Nagatsu, associate professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering at TUAT. "With the depletion of light oil resources and rising energy demands, the successful recovery of heavy oil is becoming increasingly important."

Generally, less than 10% of heavy oil may be produced from the reservoirs by natural flow after drilling the well. To yield more oil, water may be injected into the reservoir to maintain pressure in order to keep the flow moving. Engineers may also make the water more alkaline by adding sodium hydroxide or sodium carbonate to help the oil flow better. Called chemical flooding, this process often fails to yield much heavy oil, as it is too thick for even the enriched water to sweep up. Heavy oil can also be made to flow more easily through heat, but that's not a tangible solution for deep or thin reservoirs, according to Nagatsu.

"It is important to develop non-thermal chemical flooding for the recovery of heavy oil," Nagatsu said. "The key problem of chemical flooding in heavy oil reservoirs is an inefficient sweep as a result of the low mobility of the oil."

Because the viscosity of water and heavy oil differ so greatly, Nagatsu said, contemporary sweep methods are inefficient for heavy oil recovery.

To correct this inefficiency in chemical recovery, Nagatsu and his team injected calcium hydroxide into their model reservoir. The compound helps oil to flow more smoothly but is considered undesirable because it reacts with the oil to produce a metallic soap where the water and oil interface.

"The metallic soap behaves as a viscoelastic material in the pore and blocks the preferentially swept region and improves the sweep efficiency," Nagatsu said.

The metallic soap stops the sweeping flow from moving into already swept areas, forcing the forward recovery of heavy oils locked deep in rocks and crevices. In experimental testing, the method yielded 55% of oil in the reservoir, compared to a 35% recovery using alkaline water and a 33% recovery using regular water. Nagatsu noted that this method is inexpensive, can be used in a range of temperatures and it does not require energy-consuming techniques to perform.

The researchers plan to study the effectiveness of this method across crude oil viscosity ranges and in different ranges of oil reservoir permeability in laboratory experiments before moving to field tests. They would also like to engage with industry to further develop the technology for practical application, Nagatsu said.

Explore further

More information: Yuichiro Nagatsu et al, Chemical Flooding for Enhanced Heavy Oil Recovery via Chemical-Reaction-Producing Viscoelastic Material, Energy & Fuels (2020).

Provided by Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology

General Motors Aligns With Biden, Pulls Out of Lawsuit Supporting Trump

BY KATHERINE FUNG ON 11/23/20

General Motors announced Monday that it will no longer support the Trump administration in its legal efforts against California's clean-air standards and will instead work with President-elect Joe Biden.

In a letter to the nation's largest environmental groups, CEO Mary Barra said GM will pull out of the lawsuit seeking to strip California of its right to set its own clean-air standards and urged other automakers to do the same.

Barra said the company agrees with Biden's plan to expand electric vehicle use and to reduce climate-warming emissions from vehicles.

"We believe the ambitious electrification goals of the President-elect, California, and General Motors are aligned, to address climate change by drastically reducing automobile emissions," Barra wrote.

"We are confident that the Biden Administration, California, and the U.S. auto industry, which supports 10.3 million jobs, can collaboratively find the pathway that will deliver an all-electric future," she continued. "To better foster the necessary dialogue, we are immediately withdrawing from the pre-emption litigation and inviting other automakers to join us."

BY KATHERINE FUNG ON 11/23/20

General Motors announced Monday that it will no longer support the Trump administration in its legal efforts against California's clean-air standards and will instead work with President-elect Joe Biden.

In a letter to the nation's largest environmental groups, CEO Mary Barra said GM will pull out of the lawsuit seeking to strip California of its right to set its own clean-air standards and urged other automakers to do the same.

Barra said the company agrees with Biden's plan to expand electric vehicle use and to reduce climate-warming emissions from vehicles.

"We believe the ambitious electrification goals of the President-elect, California, and General Motors are aligned, to address climate change by drastically reducing automobile emissions," Barra wrote.

"We are confident that the Biden Administration, California, and the U.S. auto industry, which supports 10.3 million jobs, can collaboratively find the pathway that will deliver an all-electric future," she continued. "To better foster the necessary dialogue, we are immediately withdrawing from the pre-emption litigation and inviting other automakers to join us."

A GM worker is shown on the assembly line at the General Motors Lansing Delta Township Assembly Plant in Lansing, Michigan, on February 21. GM announced on Monday it was withdrawing support for a Trump administration lawsuit challenging California's right to set its own clean-air standards.BILL PUGLIANO/STRINGER

The announcement is a shift from GM's previous relationship with the Trump administration. Barra met with Donald Trump during his first weeks in office to urge him to loosen Obama-era standards on emissions and fuel economy standards.

Last year, automakers such as General Motors, Fiat Chrysler, Toyota, Nissan, Hyundai, Kia, Subaru, Isuzu, Suzuki, Maserati, McLaren, Aston-Martin and Ferrari intervened in a lawsuit filed by the Environmental Defense Fund against the Trump administration for climate action rollbacks, siding with the president after he revoked California's authority to set tighter restrictions.

Five other companies—BMW, Ford, Volkswagen, Volvo and Honda—backed California instead and advocated for stricter standards.

After BMW, Ford, Honda and Volkswagen signed a deal with the state's air pollution regulator, the California Air Resources Board, Trump said his administration would revoke California's ability to set clean-air standards stricter than the ones issued by federal regulators.

In response to GM's decision, the head of the Air Resources Board, Mary Nichols, called it "good news," telling the Associated Press that it had "been a while" since she last spoke with Barra, who called Nichols Monday morning.

Nichols is also a leading candidate to head the Environmental Protection Agency in the Biden administration.

"Now, the other automakers must follow GM and withdraw support for Trump's attack on clean cars," Dan Becker of the Center for Biological Diversity, one of the environmental groups Barra addressed in the letter, told the AP.

Newsweek reached out to the White House for comment but did not hear back before publication.

The announcement is a shift from GM's previous relationship with the Trump administration. Barra met with Donald Trump during his first weeks in office to urge him to loosen Obama-era standards on emissions and fuel economy standards.

Last year, automakers such as General Motors, Fiat Chrysler, Toyota, Nissan, Hyundai, Kia, Subaru, Isuzu, Suzuki, Maserati, McLaren, Aston-Martin and Ferrari intervened in a lawsuit filed by the Environmental Defense Fund against the Trump administration for climate action rollbacks, siding with the president after he revoked California's authority to set tighter restrictions.

Five other companies—BMW, Ford, Volkswagen, Volvo and Honda—backed California instead and advocated for stricter standards.

After BMW, Ford, Honda and Volkswagen signed a deal with the state's air pollution regulator, the California Air Resources Board, Trump said his administration would revoke California's ability to set clean-air standards stricter than the ones issued by federal regulators.

In response to GM's decision, the head of the Air Resources Board, Mary Nichols, called it "good news," telling the Associated Press that it had "been a while" since she last spoke with Barra, who called Nichols Monday morning.

Nichols is also a leading candidate to head the Environmental Protection Agency in the Biden administration.

"Now, the other automakers must follow GM and withdraw support for Trump's attack on clean cars," Dan Becker of the Center for Biological Diversity, one of the environmental groups Barra addressed in the letter, told the AP.

Newsweek reached out to the White House for comment but did not hear back before publication.

Growing interest in Moon resources could cause tension, scientists find

by Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

by Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

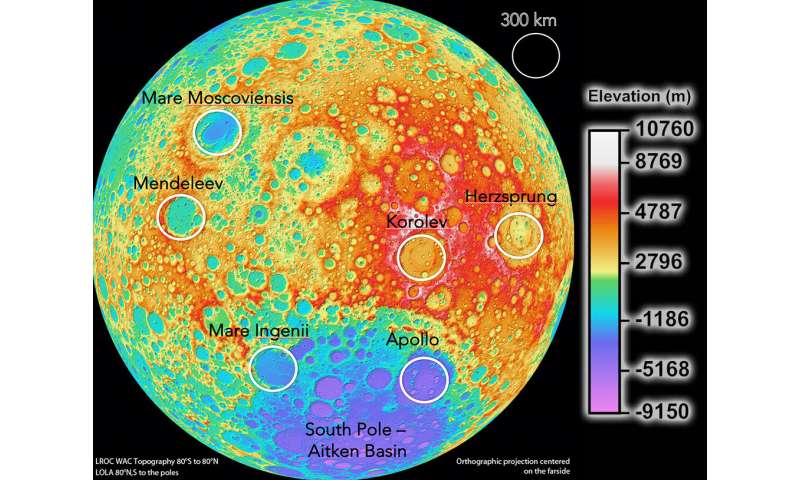

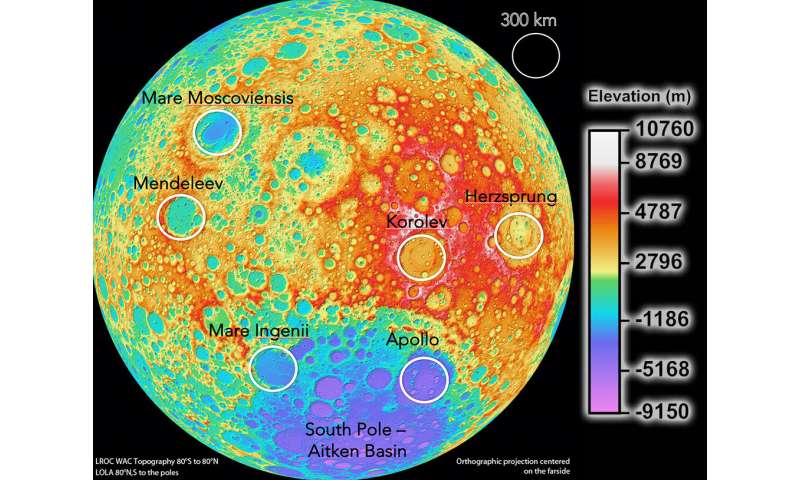

Taken by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, this image of the moon is part of the collection of the highest resolution, near-global topographic maps of the moon ever created. Overlaid on this image are some of the hotspots identified for cosmology telescopes on the moon; few ideal locations for these telescopes exist on the moon, as others conflict with the radio quiet zone.

Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center/DLR/ASU; Overlay: M. Elvis, A. Krosilowski, T. Milligan

An international team of scientists led by the Center for Astrophysics / Harvard & Smithsonian, has identified a problem with the growing interest in extractable resources on the moon: there aren't enough of them to go around. With no international policies or agreements to decide "who gets what from where," scientists believe tensions, overcrowding, and quick exhaustion of resources to be one possible future for moon mining projects. The paper published today in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A.

"A lot of people think of space as a place of peace and harmony between nations. The problem is there's no law to regulate who gets to use the resources, and there are a significant number of space agencies and others in the private sector that aim to land on the moon within the next five years," said Martin Elvis, astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian and the lead author on the paper. "We looked at all the maps of the Moon we could find and found that not very many places had resources of interest, and those that did were very small. That creates a lot of room for conflict over certain resources."

Resources like water and iron are important because they will enable future research to be conducted on, and launched from, the moon. "You don't want to bring resources for mission support from Earth, you'd much rather get them from the Moon. Iron is important if you want to build anything on the moon; it would be absurdly expensive to transport iron to the moon," said Elvis. "You need water to survive; you need it to grow food—you don't bring your salad with you from Earth—and to split into oxygen to breathe and hydrogen for fuel."

An international team of scientists led by the Center for Astrophysics / Harvard & Smithsonian, has identified a problem with the growing interest in extractable resources on the moon: there aren't enough of them to go around. With no international policies or agreements to decide "who gets what from where," scientists believe tensions, overcrowding, and quick exhaustion of resources to be one possible future for moon mining projects. The paper published today in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A.

"A lot of people think of space as a place of peace and harmony between nations. The problem is there's no law to regulate who gets to use the resources, and there are a significant number of space agencies and others in the private sector that aim to land on the moon within the next five years," said Martin Elvis, astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian and the lead author on the paper. "We looked at all the maps of the Moon we could find and found that not very many places had resources of interest, and those that did were very small. That creates a lot of room for conflict over certain resources."

Resources like water and iron are important because they will enable future research to be conducted on, and launched from, the moon. "You don't want to bring resources for mission support from Earth, you'd much rather get them from the Moon. Iron is important if you want to build anything on the moon; it would be absurdly expensive to transport iron to the moon," said Elvis. "You need water to survive; you need it to grow food—you don't bring your salad with you from Earth—and to split into oxygen to breathe and hydrogen for fuel."

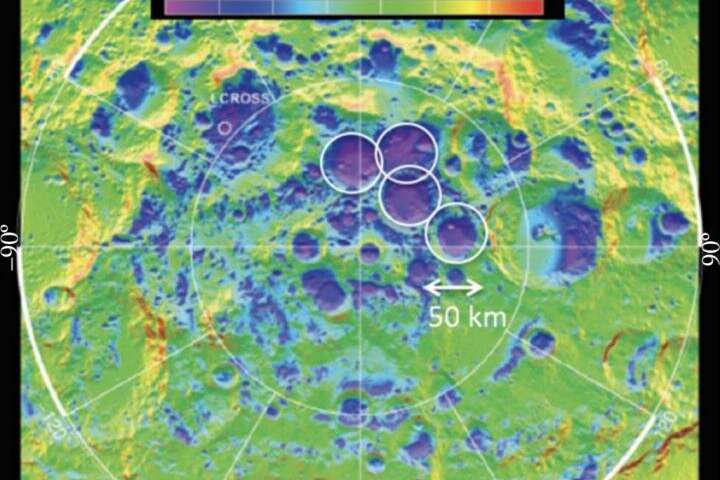

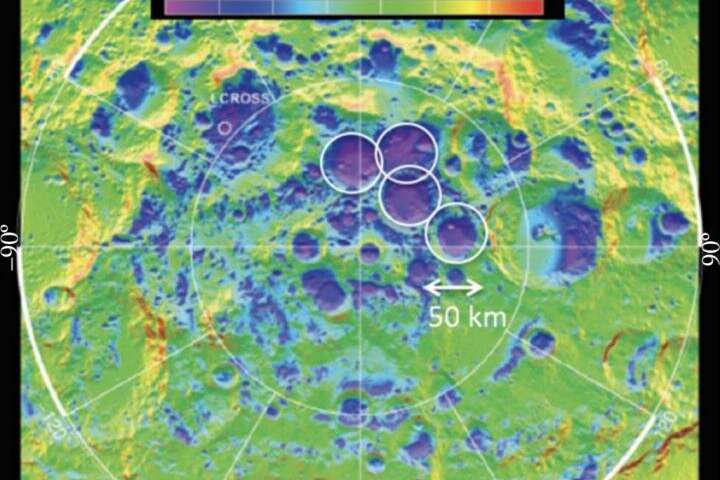

Lunar cold traps located at the South Pole of the moon, are critical to all moon-based operations because they contain frozen water molecules. Water is required for all moon-based operations because it is needed to grow food, and to break down into oxygen for breathing and hydrogen for fuel. The four white-circled regions in this image contain the coldest terrain with average annual near-surface temperatures of 25-50 K. They are about 50 km across.

Credit: David Paige, reproduced with permission.

Interest in the moon as a location for extracting resources isn't new. An extensive body of research dating back to the Apollo program has explored the availability of resources such as helium, water, and iron, with more recent research focusing on continuous access to solar power, cold traps and frozen water deposits, and even volatiles that may exist in shaded areas on the surface of the moon. Tony Milligan, a Senior Researcher with the Cosmological Visionaries project at King's College London, and a co-author on the paper said, "Since lunar rock samples returned by the Apollo program indicated the presence of Helium-3, the moon has been one of several strategic resources which have been targeted."

Although some treaties do exist, like the 1967 Outer Space Treaty—prohibiting national appropriation—and the 2020 Artemis Accords—reaffirming the duty to coordinate and notify—neither is meant for robust protection. Much of the discussion surrounding the moon, and including current and potential policy for governing missions to the satellite, have centered on scientific versus commercial activity, and who should be allowed to tap into the resources locked away in, and on, the moon. According to Milligan, it's a very 20th century debate, and doesn't tackle the actual problem. "The biggest problem is that everyone is targeting the same sites and resources: states, private companies, everyone. But they are limited sites and resources. We don't have a second moon to move on to. This is all we have to work with." Alanna Krolikowski, assistant professor of science and technology policy at Missouri University of Science and Technology (Missouri S&T) and a co-author on the paper, added that a framework for success already exists and, paired with good old-fashioned business sense, may set policy on the right path. "While a comprehensive international legal regime to manage space resources remains a distant prospect, important conceptual foundations already exist and we can start implementing, or at least deliberating, concrete, local measures to address anticipated problems at specific sites today," said Krolikowski. "The likely first step will be convening a community of prospective users, made up of those who will be active at a given site within the next decade or so. Their first order of business should be identifying worst-case outcomes, the most pernicious forms of crowding and interference, that they seek to avoid at each site. Loss aversion tends to motivate actors."

There is still a risk that resource locations will turn out to be more scant than currently believed, and scientists want to go back and get a clearer picture of resource availability before anyone starts digging, drilling, or collecting. "We need to go back and map resource hot spots in better resolution. Right now, we only have a few miles at best. If the resources are all contained in a smaller area, the problem will only get worse," said Elvis. "If we can map the smallest spaces, that will inform policymaking, allow for info-sharing and help everyone to play nice together so we can avoid conflict."

While more research on these lunar hot spots is needed to inform policy, the framework for possible solutions to potential crowding are already in view. "Examples of analogs on Earth point to mechanisms for managing these challenges. Common-pool resources on Earth, resources over which no single actor can claim jurisdiction or ownership, offer insights to glean. Some of these are global in scale, like the high seas, while other are local like fish stocks or lakes to which several small communities share access," said Krolikowski, adding that one of the first challenges for policymakers will be to characterize the resources at stake at each individual site. "Are these resources, say, areas of real estate at the high-value Peaks of Eternal Light, where the sun shines almost continuously, or are they units of energy to be generated from solar panels installed there? At what level can they can realistically be exploited? How should the benefits from those activities be distributed? Developing agreement on those questions is a likely precondition to the successful coordination of activities at these uniquely attractive lunar sites."

Explore further Cool discovery: New studies confirm moon has ice on the sunlit surface

Interest in the moon as a location for extracting resources isn't new. An extensive body of research dating back to the Apollo program has explored the availability of resources such as helium, water, and iron, with more recent research focusing on continuous access to solar power, cold traps and frozen water deposits, and even volatiles that may exist in shaded areas on the surface of the moon. Tony Milligan, a Senior Researcher with the Cosmological Visionaries project at King's College London, and a co-author on the paper said, "Since lunar rock samples returned by the Apollo program indicated the presence of Helium-3, the moon has been one of several strategic resources which have been targeted."

Although some treaties do exist, like the 1967 Outer Space Treaty—prohibiting national appropriation—and the 2020 Artemis Accords—reaffirming the duty to coordinate and notify—neither is meant for robust protection. Much of the discussion surrounding the moon, and including current and potential policy for governing missions to the satellite, have centered on scientific versus commercial activity, and who should be allowed to tap into the resources locked away in, and on, the moon. According to Milligan, it's a very 20th century debate, and doesn't tackle the actual problem. "The biggest problem is that everyone is targeting the same sites and resources: states, private companies, everyone. But they are limited sites and resources. We don't have a second moon to move on to. This is all we have to work with." Alanna Krolikowski, assistant professor of science and technology policy at Missouri University of Science and Technology (Missouri S&T) and a co-author on the paper, added that a framework for success already exists and, paired with good old-fashioned business sense, may set policy on the right path. "While a comprehensive international legal regime to manage space resources remains a distant prospect, important conceptual foundations already exist and we can start implementing, or at least deliberating, concrete, local measures to address anticipated problems at specific sites today," said Krolikowski. "The likely first step will be convening a community of prospective users, made up of those who will be active at a given site within the next decade or so. Their first order of business should be identifying worst-case outcomes, the most pernicious forms of crowding and interference, that they seek to avoid at each site. Loss aversion tends to motivate actors."

There is still a risk that resource locations will turn out to be more scant than currently believed, and scientists want to go back and get a clearer picture of resource availability before anyone starts digging, drilling, or collecting. "We need to go back and map resource hot spots in better resolution. Right now, we only have a few miles at best. If the resources are all contained in a smaller area, the problem will only get worse," said Elvis. "If we can map the smallest spaces, that will inform policymaking, allow for info-sharing and help everyone to play nice together so we can avoid conflict."

While more research on these lunar hot spots is needed to inform policy, the framework for possible solutions to potential crowding are already in view. "Examples of analogs on Earth point to mechanisms for managing these challenges. Common-pool resources on Earth, resources over which no single actor can claim jurisdiction or ownership, offer insights to glean. Some of these are global in scale, like the high seas, while other are local like fish stocks or lakes to which several small communities share access," said Krolikowski, adding that one of the first challenges for policymakers will be to characterize the resources at stake at each individual site. "Are these resources, say, areas of real estate at the high-value Peaks of Eternal Light, where the sun shines almost continuously, or are they units of energy to be generated from solar panels installed there? At what level can they can realistically be exploited? How should the benefits from those activities be distributed? Developing agreement on those questions is a likely precondition to the successful coordination of activities at these uniquely attractive lunar sites."

Explore further Cool discovery: New studies confirm moon has ice on the sunlit surface

More information: Martin Elvis et al, Concentrated lunar resources: imminent implications for governance and justice, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences (2020). DOI: 10.1098/rsta.2019.0563

Journal information: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A

Provided by Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

Provided by Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

Darwin's handwritten pages from 'On the Origin of Species' go online for the first time

by National University of Singapore

More information: Darwin online: darwin-online.org.uk/whatsnew.html

Provided by National University of Singapore

by National University of Singapore

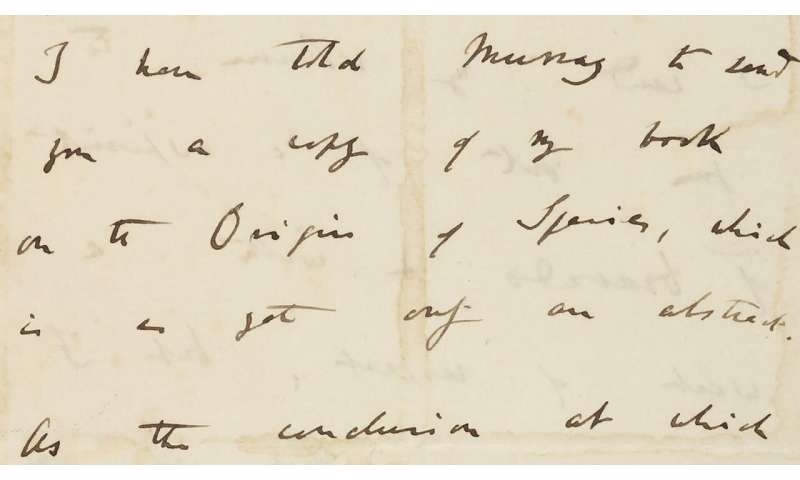

Darwin's handwritten letter to his former geology professor at Cambridge where he first mentioned his radical new book, On the Origin of Species Credit: Reproduced with the kind permission of a private collection, USA, and William Huxley Darwin

An extraordinary collection of priceless manuscripts of naturalist Charles Darwin goes online today, including two rare pages from the original draft of On the Origin of Species.

These documents will be added to Darwin Online, a website which contains not only the complete works of Darwin, but is possibly the most comprehensive scholarly portal on any historical individual in the world. The website is helmed by Dr. John van Wyhe, an eminent historian of science. He is a Senior Lecturer at the National University of Singapore's (NUS) Department of Biological Sciences, and Tembusu College.

"Darwin wrote the first draft of On the Origin of Species by hand. But the historical significance of this work was not yet known and almost all the manuscript was lost—with his children even using the pages as drawing paper! As such, these two pages are extremely rare survivors, and give unprecedented insight into the making of the book that changed the world," explained Dr. van Wyhe.

Access to these rare artifacts comes exactly 161 years after the initial publication of On the Origin of Species on 24 November 1859, and coincides with Evolution Day, which commemorates the anniversary of this revolutionary book.

An unbelievably rare collection

Despite being one of the most important scientific works of all time, only a few portions of the original handwritten On the Origin of Species manuscript survive. Those which are being added to the Darwin Online project are two of only nine pages in private hands.

Other important manuscripts going online today include a draft page from Darwin's other most revolutionary work The Descent of Man, and even the receipt for the book from Darwin's publisher, "for the Sum of Six Hundred and thirty pounds for the first edition, consisting of 2,500 copies, of my work on the 'Descent of Man'."

There are also two draft pages from Darwin's seminal The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

Unprecedented insights into Darwin's work

A page that has never been made public before is some reading notes on ants that Darwin made during his research for On the Origin of Species. The notes informed his examination of slave-making ants which became one of the most widely talked about parts of his famous book.

In addition, there are three very important letters by Darwin. One 1859 letter was written to his former geology professor at Cambridge, Adam Sedgwick, as Darwin nervously sends his radical new On the Origin of Species. Two other important letters are to his colleagues, the biologist T. H. Huxley and the botanist Asa Gray.

Darwin's handwriting is notoriously difficult to read. As such, the documents have been transcribed, and can be viewed side-by-side with the original manuscript. The newly released documents can be viewed at Darwin Online.

"Instead of being locked away out of public view, by adding these documents to Darwin Online they became freely available to anyone in the world", shared Dr. van Wyhe.

Explore furtherHistorian re-constructs Charles Darwin's Beagle library online

An extraordinary collection of priceless manuscripts of naturalist Charles Darwin goes online today, including two rare pages from the original draft of On the Origin of Species.

These documents will be added to Darwin Online, a website which contains not only the complete works of Darwin, but is possibly the most comprehensive scholarly portal on any historical individual in the world. The website is helmed by Dr. John van Wyhe, an eminent historian of science. He is a Senior Lecturer at the National University of Singapore's (NUS) Department of Biological Sciences, and Tembusu College.

"Darwin wrote the first draft of On the Origin of Species by hand. But the historical significance of this work was not yet known and almost all the manuscript was lost—with his children even using the pages as drawing paper! As such, these two pages are extremely rare survivors, and give unprecedented insight into the making of the book that changed the world," explained Dr. van Wyhe.

Access to these rare artifacts comes exactly 161 years after the initial publication of On the Origin of Species on 24 November 1859, and coincides with Evolution Day, which commemorates the anniversary of this revolutionary book.

An unbelievably rare collection

Despite being one of the most important scientific works of all time, only a few portions of the original handwritten On the Origin of Species manuscript survive. Those which are being added to the Darwin Online project are two of only nine pages in private hands.

Other important manuscripts going online today include a draft page from Darwin's other most revolutionary work The Descent of Man, and even the receipt for the book from Darwin's publisher, "for the Sum of Six Hundred and thirty pounds for the first edition, consisting of 2,500 copies, of my work on the 'Descent of Man'."

There are also two draft pages from Darwin's seminal The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

Unprecedented insights into Darwin's work

A page that has never been made public before is some reading notes on ants that Darwin made during his research for On the Origin of Species. The notes informed his examination of slave-making ants which became one of the most widely talked about parts of his famous book.

In addition, there are three very important letters by Darwin. One 1859 letter was written to his former geology professor at Cambridge, Adam Sedgwick, as Darwin nervously sends his radical new On the Origin of Species. Two other important letters are to his colleagues, the biologist T. H. Huxley and the botanist Asa Gray.

Darwin's handwriting is notoriously difficult to read. As such, the documents have been transcribed, and can be viewed side-by-side with the original manuscript. The newly released documents can be viewed at Darwin Online.

"Instead of being locked away out of public view, by adding these documents to Darwin Online they became freely available to anyone in the world", shared Dr. van Wyhe.

Explore furtherHistorian re-constructs Charles Darwin's Beagle library online

More information: Darwin online: darwin-online.org.uk/whatsnew.html

Provided by National University of Singapore

Not just lizards—alligators can regrow their tails too

by Arizona State University

American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis)

Credit: Ruth Elsey and the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

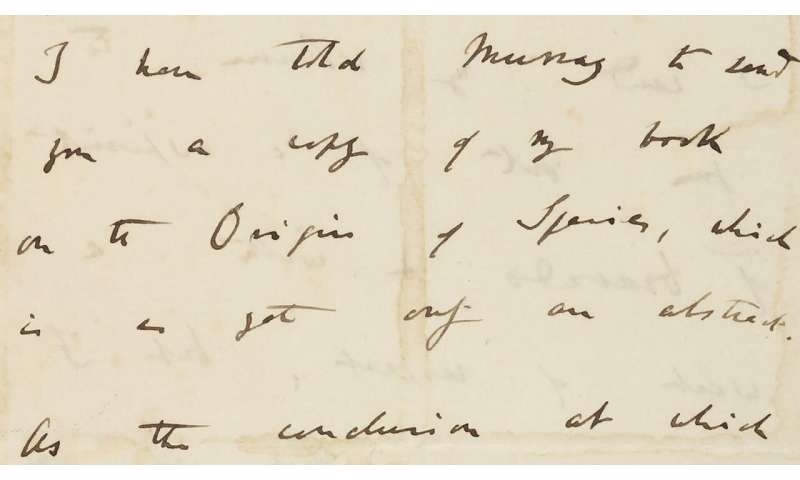

American alligators are about as close to dinosaurs as you can get in modern times, and can grow up to 14 feet in length. While much smaller reptiles such as lizards are able to regenerate their tails, the question of whether the much larger alligator is able to regrow their massive tails has not been well studied. A team of researchers from Arizona State University and the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries have uncovered that young alligators have the ability to regrow their tails up to three-quarters of a foot, or 18% of their total body length.=

An interdisciplinary team of scientists used advanced imaging techniques combined with demonstrated methods of studying anatomy and tissue organization to examine the structure of these regrown tails. They found that these new tails were complex structures with a central skeleton composed of cartilage surrounded by connective tissue that was interlaced with blood vessels and nerves. They speculate that regrowing their tails gives the alligators a functional advantage in their murky aquatic habitats.

The findings are published in the journal Scientific Reports.

"What makes the alligator interesting, apart from its size, is that the regrown tail exhibits signs of both regeneration and wound healing within the same structure," said Cindy Xu, a recent Ph.D. graduate from ASU's molecular and cellular biology program and lead author of the paper. " Regrowth of cartilage, blood vessels, nerves, and scales were consistent with previous studies of lizard tail regeneration from our lab and others. However, we were surprised to discover scar-like connective tissue in place of skeletal muscle in the regrown alligator tail. Future comparative studies will be important to understand why regenerative capacity is variable among different reptile and animal groups."

https://phys.org/news/2020-11-lizardsalligators-regrow-tails.html

American alligators are about as close to dinosaurs as you can get in modern times, and can grow up to 14 feet in length. While much smaller reptiles such as lizards are able to regenerate their tails, the question of whether the much larger alligator is able to regrow their massive tails has not been well studied. A team of researchers from Arizona State University and the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries have uncovered that young alligators have the ability to regrow their tails up to three-quarters of a foot, or 18% of their total body length.=

An interdisciplinary team of scientists used advanced imaging techniques combined with demonstrated methods of studying anatomy and tissue organization to examine the structure of these regrown tails. They found that these new tails were complex structures with a central skeleton composed of cartilage surrounded by connective tissue that was interlaced with blood vessels and nerves. They speculate that regrowing their tails gives the alligators a functional advantage in their murky aquatic habitats.

The findings are published in the journal Scientific Reports.

"What makes the alligator interesting, apart from its size, is that the regrown tail exhibits signs of both regeneration and wound healing within the same structure," said Cindy Xu, a recent Ph.D. graduate from ASU's molecular and cellular biology program and lead author of the paper. " Regrowth of cartilage, blood vessels, nerves, and scales were consistent with previous studies of lizard tail regeneration from our lab and others. However, we were surprised to discover scar-like connective tissue in place of skeletal muscle in the regrown alligator tail. Future comparative studies will be important to understand why regenerative capacity is variable among different reptile and animal groups."

https://phys.org/news/2020-11-lizardsalligators-regrow-tails.html

Play3-D reconstruction video of the cartilage tube found in the regrown alligator tail. This structure extends the length of the regrown tail and features randomly distributed pores. Credit: Arizona State University

"The spectrum of regenerative ability across species is fascinating, clearly there is a high cost to producing new muscle," said Jeanne Wilson-Rawls, co-senior author and associate professor with ASU's School of Life Sciences. "

"Staff biologists in our Alligator Research and Management Program have been pleased to partner with Dr. Kusumi at Arizona State University for many years," said Ruth M. Elsey, a Biologist Manager with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. "We see alligators in the field with some indication of possible regrowth of tail tissue, but their expertise led to the current study detailing the histological changes associated with the capacity for possible partial tail regrowth or wound re

Alligators, lizards, and humans all belong to a group of animals with backbones called amniotes. While the interdisciplinary team has previous studied the ability of lizards to regenerate their tails, this finding of regrowth of complex new tails in the alligator gives further information about the process in amniotes.

"The spectrum of regenerative ability across species is fascinating, clearly there is a high cost to producing new muscle," said Jeanne Wilson-Rawls, co-senior author and associate professor with ASU's School of Life Sciences. "

"Staff biologists in our Alligator Research and Management Program have been pleased to partner with Dr. Kusumi at Arizona State University for many years," said Ruth M. Elsey, a Biologist Manager with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. "We see alligators in the field with some indication of possible regrowth of tail tissue, but their expertise led to the current study detailing the histological changes associated with the capacity for possible partial tail regrowth or wound re

Alligators, lizards, and humans all belong to a group of animals with backbones called amniotes. While the interdisciplinary team has previous studied the ability of lizards to regenerate their tails, this finding of regrowth of complex new tails in the alligator gives further information about the process in amniotes.

The regrown alligator tail is different from the original tail. Regrown scales are densely arranged and lack dorsal scutes (top right). An unsegmented tube of cartilage (yellow) replaces bone (tan) in the regrown tail. Moreover, the regrown tail lacks skeletal muscle (red) and instead, there is an abundance of fibrous connective tissue (pink). Credit: Arizona State University

"The ancestors of alligators and dinosaurs and birds split off around 250 million years ago," said co-senior author Kenro Kusumi, professor and director of ASU's School of Life Sciences and associate dean in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. "Our finding that alligators have retained the cellular machinery to regrow complex tails while birds have lost that ability raises the question of when during evolution this ability was lost. Are there fossils out there of dinosaurs, whose lineage led to modern birds, with regrown tails? We haven't found any evidence of that so far in the published literature."

"If we understand how different animals are able to repair and regenerate tissues, this knowledge can then be leveraged to develop medical therapies," said Rebecca Fisher, co-author and professor with the University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix and ASU's School of Life Sciences. The researchers hope their findings will help lead to discoveries of new therapeutic approaches to repairing injuries and treating diseases such as arthritis.

Explore further

"The ancestors of alligators and dinosaurs and birds split off around 250 million years ago," said co-senior author Kenro Kusumi, professor and director of ASU's School of Life Sciences and associate dean in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. "Our finding that alligators have retained the cellular machinery to regrow complex tails while birds have lost that ability raises the question of when during evolution this ability was lost. Are there fossils out there of dinosaurs, whose lineage led to modern birds, with regrown tails? We haven't found any evidence of that so far in the published literature."

"If we understand how different animals are able to repair and regenerate tissues, this knowledge can then be leveraged to develop medical therapies," said Rebecca Fisher, co-author and professor with the University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix and ASU's School of Life Sciences. The researchers hope their findings will help lead to discoveries of new therapeutic approaches to repairing injuries and treating diseases such as arthritis.

Explore further

How lizards regenerate their tails: Researchers discover genetic 'recipe'

More information: Cindy Xu et al, Anatomical and histological analyses reveal that tail repair is coupled with regrowth in wild-caught, juvenile American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis), Scientific Reports (2020).

More information: Cindy Xu et al, Anatomical and histological analyses reveal that tail repair is coupled with regrowth in wild-caught, juvenile American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis), Scientific Reports (2020).

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-77052-8

Journal information: Scientific Reports

Provided by Arizona State University

Journal information: Scientific Reports

Provided by Arizona State University

Secrets of the 'lost crops' revealed where bison roam

by Talia Ogliore, Washington University in St. Louis

More information: Natalie G Mueller et al. Bison, anthropogenic fire, and the origins of agriculture in eastern North America, The Anthropocene Review (2020).

Provided by Washington University in St. Louis

by Talia Ogliore, Washington University in St. Louis

American bison at the Joseph H. Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in Oklahoma.

Credit: Natalie Mueller

Blame it on the bison.

If not for the wooly, boulder-sized beasts that once roamed North America in vast herds, ancient people might have looked past the little barley that grew under those thundering hooves. But the people soon came to rely on little barley and other small-seeded native plants as staple food.

New research from Washington University in St. Louis helps flesh out the origin story for the so-called "lost crops." These plants may have fed as many Indigenous people as maize, but until the 1930s had been lost to history.

As early as 6,000 years ago, people in the American Northeast and Midwest were using fire to maintain the prairies where bison thrived. When Europeans slaughtered the bison to near-extinction, the plants that relied on these animals to disperse their seeds began to diminish as well.

"Prairies have been ignored as possible sites for plant domestication, largely because the disturbed, biodiverse tallgrass prairies created by bison have only been recreated in the past three decades after a century of extinction," said Natalie Mueller, assistant professor of archaeology in Arts & Sciences.

Following the bison

In a new publication in The Anthropocene Review, Mueller reports on four field visits during 2019 to the Joseph H. Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in eastern Oklahoma, the largest protected remnant of tallgrass prairie left on Earth. The roughly 40,000-acre preserve is home to about 2,500 bison today.

Mueller waded into the bison wallows after years of attempting to grow the lost crops from wild-collected seed in her own experimental gardens.

"One of the great unsolved mysteries about the origins of agriculture is why people chose to spend so much time and energy cultivating plants with tiny, unappetizing seeds in a world full of juicy fruits, savory nuts and plump roots," Mueller said.

They may have gotten their ideas from following bison.

Anthropologists have struggled to understand why ancient foragers chose to harvest plants that seemingly offer such a low return on labor.

"Before any mutualistic relationship could begin, people had to encounter stands of seed-bearing annual plants dense and homogeneous enough to spark the idea of harvesting seed for food," Mueller said.

Recent reintroductions of bison to tallgrass prairies offer some clues.

For the first time, scientists like Mueller are able to study the effects of grazing on prairie ecosystems. Turns out that munching bison create the kind of disturbance that opens up ideal habitats for annual forbs and grasses—including the crop progenitors that Mueller studies.

Credit: Washington University in St. Louis

Harvesting at the wallow's edge

At the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve, Mueller and her team members got some tips from local expert Mike Palmer.

"Mike let us know roughly where on the prairie to look for the bison," Mueller said. "His occurrence data were at the resolution of roughly a square mile, but that helps when you're on a 60-square-mile grassland.

"I thought it would be hard to find trails to follow before I went out there, but it's not," she said. "They are super easy to find and easy to follow, so much so that I can't imagine humans moving through a prairie any other way!"

Telltale signs of grazing and trampling marked the "traces" that bison make through shoulder-high grasses. By following recently trodden paths through the prairie, the scientists were able to harvest seeds from continuous stands of little barley and maygrass during their June visit, and sumpweed in October.

"While much more limited in distribution, we also observed a species of Polygonum closely related to the crop progenitor and wild sunflowers in bison wallows and did not encounter either of these species in the ungrazed areas," Mueller said.

It was easier to move through the prairie on the bison paths than to venture off them.

"The ungrazed prairie felt treacherous because of the risk of stepping into burrows or onto snakes," she said.

With few landscape features for miles in any direction, the parts of the prairie that were not touched by bison could seem disorienting.

"These observations support a scenario in which ancient people would have moved through the prairie along traces, where they existed," Mueller said. "If they did so, they certainly would have encountered dense stands of the same plant species they eventually domesticated."

Diverse landscapes

Mueller encourages others to consider the role of bison as 'co-creators'—along with Indigenous peoples—of landscapes of disturbance that gave rise to greater diversity and more agricultural opportunities.

"Indigenous people in the Midcontinent created resilient and biodiverse landscapes rich in foods for people," she said. "They managed floodplain ecosystems rather than using levees and dams to convert them to monocultures. They used fire and multispecies interactions to create mosaic prairie-savanna-woodland landscapes that provided a variety of resources on a local scale."

Mueller is now growing seeds that she harvested from plants at the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve and also seeds that she separated from bison dung from the preserve. In future years, Mueller plans to return to the preserve and also to visit other prairies in order to quantify the distribution and abundance of crop progenitors under different management regimes.

"These huge prairies would not have existed if the native Americans were not maintaining them," using fire and other means, Mueller said. But to what end? Archaeologists have not found caches of bones or other evidence to indicate that Indigenous people were eating lots of prairie animals. Perhaps the ecosystems created by bison and anthropogenic fire benefited the lost crops.

"We don't think of the plants they were eating as prairie plants," she said. "However, this research suggests that they actually are prairie plants—but they only occur on prairies if there are bison.

"I think we're just beginning to understand what the botanical record was telling us," Mueller said. "People were getting a lot more food from the prairie than we thought."

Explore further

Five facts about bison, the new US national mammal

Blame it on the bison.

If not for the wooly, boulder-sized beasts that once roamed North America in vast herds, ancient people might have looked past the little barley that grew under those thundering hooves. But the people soon came to rely on little barley and other small-seeded native plants as staple food.

New research from Washington University in St. Louis helps flesh out the origin story for the so-called "lost crops." These plants may have fed as many Indigenous people as maize, but until the 1930s had been lost to history.

As early as 6,000 years ago, people in the American Northeast and Midwest were using fire to maintain the prairies where bison thrived. When Europeans slaughtered the bison to near-extinction, the plants that relied on these animals to disperse their seeds began to diminish as well.

"Prairies have been ignored as possible sites for plant domestication, largely because the disturbed, biodiverse tallgrass prairies created by bison have only been recreated in the past three decades after a century of extinction," said Natalie Mueller, assistant professor of archaeology in Arts & Sciences.

Following the bison

In a new publication in The Anthropocene Review, Mueller reports on four field visits during 2019 to the Joseph H. Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in eastern Oklahoma, the largest protected remnant of tallgrass prairie left on Earth. The roughly 40,000-acre preserve is home to about 2,500 bison today.

Mueller waded into the bison wallows after years of attempting to grow the lost crops from wild-collected seed in her own experimental gardens.

"One of the great unsolved mysteries about the origins of agriculture is why people chose to spend so much time and energy cultivating plants with tiny, unappetizing seeds in a world full of juicy fruits, savory nuts and plump roots," Mueller said.

They may have gotten their ideas from following bison.

Anthropologists have struggled to understand why ancient foragers chose to harvest plants that seemingly offer such a low return on labor.