China’s power crisis: Outrage over power outages may affect Xi’s green initiatives

If China continues to undergo a major energy crunch, its green policy might be under jeopardy

The recent restrictions on power consumption in China disrupted manufacturing activities, and a cloud hangs over technology supply chains. In addition to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) efforts to rein in the real estate sector, electricity woes pose a new challenge to the country’s fledgling economic growth and CCP’s ambitions in the field of global climate governance.

In addition to 20 provinces, China’s showcase cities—Beijing and Shanghai—that are home to nearly 22 million and 26 million inhabitants respectively, have experienced power outages. On average, mercury dips till -6°C in the capital, this increases demand for heating, and worries are abound about whether the power crunch will extend into winter.

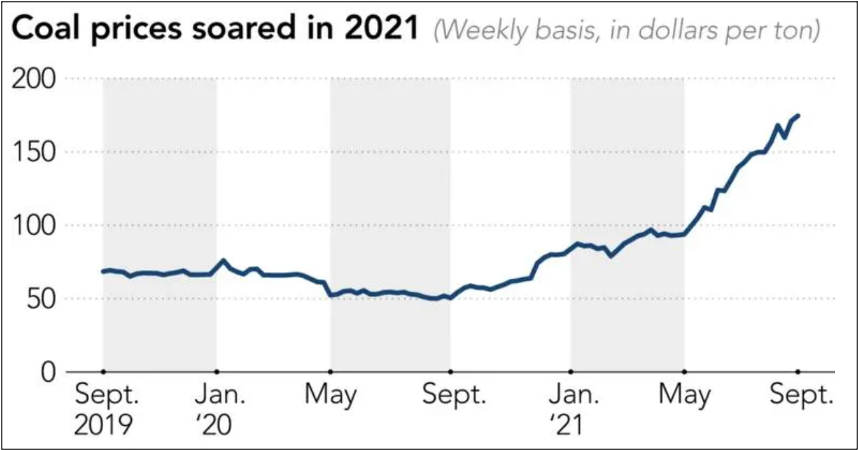

A part of the problem stems from the steadily climbing coal prices. Around September 2020, coal prices hovered around US $50 per tonne, but it soared to US $177.5 last month—the highest it has climbed to in more than a decade (see graphic).

Coal imports have also been hampered by geopolitical tussles. China uses more than 3 billion tonnes of thermal coal each year; nearly 2 percent of China’s total consumed thermal coal came from Australia due to its reasonable price and superior quality. But the People’s Republic prohibited import of coal from Australia after it sought for an international inquiry into the origins of the coronavirus.

Usually, power generation groups fill their coal stocks in September ahead of the winter months. However, according to Sinolink Securities, this year’s September stockpile of thermal coal by six major power-generation groups was only enough to meet a fortnight’s requirement. With the price of coal rising, power generation firms are reluctant to produce sufficient electricity to meet demand; since tariffs are capped, the revenue accrued is not enough to cover costs. In China, more than half of all power is generated from coal. Coal is the single biggest contributor to climate change. The burning of coal accounts for 46 percent of carbon dioxide emissions globally, and over 70 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions are from the electricity sector. China tops the chart of polluters accounting for nearly 27 percent of global emissions. Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, a landmark international treaty on cutting greenhouse gas emissions, China agreed to achieve the peaking of carbon dioxide emissions around 2030, and to increase the proportion of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 20 percent.

How nations fare on pollution

RANK NATION GLOBAL EMISSIONS (% in ’17)

1 China 27.2 %

2 US 14.6%

3 India 6.8%

4 Russia 4.7%

5 Japan 3.3%

Source: World Economic Forum

Climate change has been influenced not just by the vagaries of rising emissions, but also partisan politics. The Paris deal, which was seen as then US President Barack Obama’s political legacy, was reviewed by his successor. Within months of Donald Trump’s inauguration as US President in 2017, his administration rolled back the previous ban on mining coal in the nation. He later announced that the US was pulling out of the covenant, citing that permitting China and India to use fossil fuels under the treaty while America had to curb its carbon was unfair. Coincidentally, the withdrawal came into effect amidst the counting of votes in the contentious 2020 Presidential election, which Trump lost. Under incumbent President Joe Biden, climate governance is a top priority. In February, America re-joined the Paris Agreement. The appointment of a heavyweight like former Secretary of State, John Kerry, as special envoy on climate change signals the new American administration’s aim of reasserting its lead in the fight to combat global warming.

The significance of the US walking out of the Paris deal has not been lost on China. The Trump interlude gave China a good opening to pose as a responsible stakeholder in the effort to tackle climate change and pollution. At the United Nations Summit on Biodiversity in September 2020, Xi announced his ‘green’ plan for China to become carbon neutral by 2060.

The significance of the US walking out of the Paris deal has not been lost on China. The Trump interlude gave China a good opening to pose as a responsible stakeholder in the effort to tackle climate change and pollution. At the United Nations Summit on Biodiversity in September 2020, Xi announced his ‘green’ plan for China to become carbon neutral by 2060.

In April, Biden called the heads of nations responsible for nearly 80 percent of global emissions to a virtual summit, seeking pledges to lowering emissions. State-run media in China portrayed this move as an effort to establish a climate-cooperation clique centred around the US to boost its leadership on international issues. In turn, China invited Kerry to discuss climate issues, around the same time it began vociferously opposing Japan’s plan to release radioactive water from the wrecked Fukushima nuclear plant into the Pacific Ocean. It slammed the US for supporting Japan and accused it of double standards on the issue of environmental protection. Through this episode, China demonstrated its ambition to steer international climate governance, and not be an adjunct to an American-led initiative.

With America back in the game, China increased its stakes in this one-upmanship. Due to Xi’s focus to claim the green mantle, the National Energy Administration (NEA) sought to cut coal use to 56 percent of total energy consumption in 2021, down from 57 percent. In line with Xi’s commitment to reach a peak in carbon dioxide emissions by 2030, the guidelines issued in April laid emphasis on meeting nearly 11 percent of the country’s electricity consumption through wind and solar power. Xi was betting big on e-vehicles, but charging stations for new energy vehicles suspended operations in parts of China in the wake of the outages. These developments may in future put the brakes on the decisions of some buyers to switch to new energy vehicles.

China is feeling the pinch with factory activity contracting in September due to curbs on electricity use and increased input prices. The manufacturing Purchasing Manager’s Index—an indicator of business activity—plummeted to 49.6 in September from 50.1 in the previous month. While the crisis was unfolding, Xi visited a ‘green’ industrial unit in Shaanxi that uses coal to produce chemical products like methanol to polyolefins without generating much waste water. In his address there, he highlighted the need for environmental protection. Grandstanding notwithstanding, he faces tough choices. First, loosening controls on electricity tariffs may have a bearing on production costs that will ultimately hit Chinese buyers and affect national competitiveness. Second, lifting the ban on Australian coal may cause Xi to lose face ahead of the key 2022 National Congress. The bumpy ride to clean energy may thus force Xi to put his green policy on the backburner.