REST IN POWERbell hooks obituary

Trailblazing writer, activist and cultural theorist who made a pivotal contribution to Black feminist thought

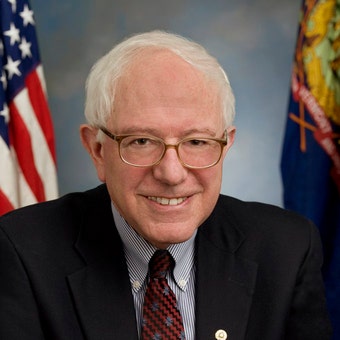

bell hooks in 2018. She wrote 40 books in a career spanning more than four decades. Photograph: Holler Home/The Orchard/Kobal/Shutterstock

Margaret Busby

Fri 17 Dec 2021 14.57 GMT

A trailblazing cultural theorist and activist, public intellectual, teacher and feminist writer, bell hooks, who has died of kidney failure aged 69, authored around 40 books in a career spanning more than four decades. Exploring the intersecting oppressions of gender, race and class, her writings additionally reflected her concerns with issues related to art, history, sexuality, psychology and spirituality, ultimately with love at the heart of community healing.

Using storytelling as effectively as social theory, she was creatively agile in a range of genres, including poetry, essays, memoir, self-help and children’s books, as well as appearing in documentary films and working in academia. However, her outstanding legacy may be her pivotal contribution to Black feminist thought, first articulated in her 1981 book Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, which examined both historical racism and sexism, going back to the treatment of Black women from enslavement to give context to continuing racial and sexual injustice.

Advertisement

The daughter of Veodis Watkins, a postal worker, and his wife, Rosa Bell (nee Oldham), she was born Gloria Jean Watkins in the small rural town of Hopkinsville, Kentucky, and her upbringing was affected by being part of a working-class African-American family in the US south, initially educated at racially segregated schools. A gifted child, she enjoyed the poetry of William Wordsworth, Langston Hughes, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Gwendolyn Brooks, and was encouraged to write verse of her own well before she reached her teens. Scholarships enabled her to study at Stanford University, in California, where she earned a BA in English in 1973, and she took an MA in English from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1976.

That year she began teaching at the University of Southern California, and during her time there her first publication, the poetry chapbook And There We Wept (1978), appeared under the pseudonym bell hooks – a name she adopted in tribute to her maternal great-grandmother, styling it in lowercase so as to keep the focus on her work rather than on her own persona.

She had begun writing her major work, Ain’t I a Woman – its title referencing a celebrated speech by the 19th-century Black abolitionist Sojourner Truth – as an undergraduate. Harshly criticised from some quarters, the book eventually achieved influential status as a classic that centres Black womanhood. Another key title, Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (1984), is a critique of mainstream feminist theory in which Black women exist only on the margins, with the women’s liberation movement being primarily structured around issues relevant to white women with class privilege.

The journalist and media consultant Joan Harris recalled the historical context, when “it was almost considered anathema, almost traitorous, if you were Black also to be a ‘feminist’” and joining a white women’s group was not an option, given the differing concerns at the time. Harris said: “Bell’s work clarified things … Her work, her presence, made me, and so many others, feel validated during a truly fraught time.”

During the 1980s and 1990s, hooks taught at a number of educational institutions, among them Yale University, Oberlin College and the City College of New York. In 2004 she joined the faculty of Berea College in her native Kentucky, where in 2014 the bell hooks Institute was established. She received the American Book awards/Before Columbus Foundation award for Yearning: Race, Gender and Cultural Politics (1990) and was nominated for an NAACP Image award for her 1999 children’s book Happy to Be Nappy.

An advocate of anti-racist, anti-sexist and anti-capitalist politics, she produced radical writings that shaped popular and academic discourse. Her books illuminated a wide range of topics, evidenced by just a selection of the titles: Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black (1989); Breaking Bread: Insurgent Black Intellectual Life (with Cornel West, 1991); Black Looks: Race and Representation (1992); Reel to Real: Race, Sex and Class at the Movies (1996); We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity (2004); and Soul Sister: Women, Friendship, and Fulfillment (2005).

Her writing resonated far beyond the US, and her work was translated into 15 languages. Invited to London for the International Book Fair of Radical Black and Third World Books in 1991, she spoke and took part in debates and readings, engaging with local activists. In my 1992 anthology Daughters of Africa I included the title essay from her collection Talking Back, which in many ways encapsulates the origins, motivation and inspiration that propelled her forward from early in life.

“In the world of the southern black community I grew up in, ‘back talk’ and ‘talking back’ meant speaking as an equal to an authority figure. It meant daring to disagree and sometimes it meant just having an opinion,” she explained. For a child, to speak when not spoken to was to invite punishment, so was a courageous act, an act of risk and daring. It was in that world that the craving was born in her “to have a voice, and not just any voice, but one that could be identified as belonging to me … Certainly for black women, our struggle has not been to emerge from silence into speech but to change the nature and direction of our speech, to make a speech that compels listeners, one that is heard.”

Her spirit refused to be crushed by the somewhat harsh reception her first work received and, tellingly, she wrote: “Now when I ponder the silences, the voices that are not heard, the voices of those wounded and/or oppressed individuals who do not speak or write, I contemplate the acts of persecution, torture – the terrorism that breaks spirits, that makes creativity impossible. I write these words to bear witness to the primacy of resistance struggle in any situation of domination (even within family life); to the strength and power that emerges from sustained resistance and the profound conviction that these forces can be healing, can protect us from dehumanisation and despair.”

For hooks, it was “that act of speech, of ‘talking back’, that is no mere gesture of empty words, that is the expression of our movement from object to subject – the liberated voice”.

She is survived by four sisters, Sarah, Valeria, Angela and Gwenda, and a brother, Kenneth.

bell hooks (Gloria Jean Watkins), writer, born 25 September 1952; died 15 December 2021

bell hooks’ writing told Black women and girls to trust themselves

Deborah Douglas

The feminist writer created a vocabulary that helped us to learn, grow, and forgive – and above all to understand

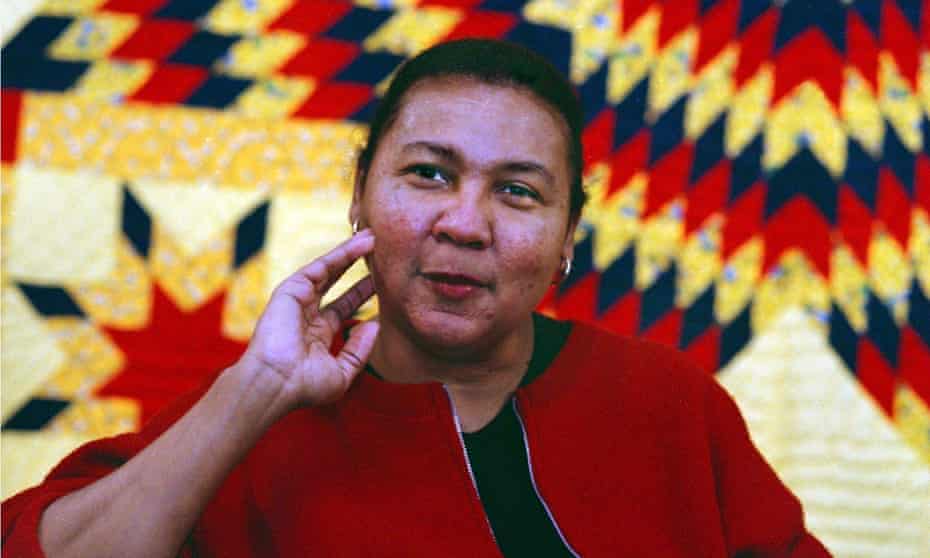

‘The beauty of hooks was her ability to bring philosophy to the people.’

Photograph: Holler Home/The Orchard/Kobal/Shutterstock

Fri 17 Dec 2021

Having just the right words to explain what’s happening keeps you from feeling, well, crazy.

When the world learned of the passing of bell hooks, the renowned feminist, public intellectual, author, and professor on Wednesday, at her home in Berea, Kentucky, it was the value and accessibility of her words that resonated with Black women, whose understanding of themselves and their own work was transformed by hooks.

One day in her 20s, the right words came to Natalie Bullock Brown

Her then boyfriend gave her copy of Sisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-Recovery (1993), which made her feel seen and loved. Through tears and hard swallows, Bullock Brown, now a documentary film-maker and interdisciplinary studies professor at North Carolina State University, revealed how the world broke open when she first inhaled those pages.

hooks “inspired and motivated me to want to understand what I was experiencing,” said Bullock Brown, describing the ways she had come crashing into sexism and racism as a girl, then a woman. “I felt pricked. I felt like, ‘Oh my, God, she’s talking to me.’ I wanted to heal. That’s really what Sisters of the Yam is about.”

For so many, the beauty of hooks, known for such titles as Ain’t I A Woman? (1981), All About Love (1999), and Teaching to Transgress (1994), was her ability to bring philosophy to the people, said Saida Grundy, a feminist sociologist of race and ethnicity and a professor at Boston University.

Hers was a language that radically changed how Black women process their lives

“There is this idea that of all the humanities, philosophy is sort of the most erudite, the most prestigious or the most inaccessible, and what she’s doing is inviting Black people in particular but really marginalized people [in general] into this space of thinking about their own experience in ways of critical thinking or esoteric exercise,” Grundy said.

In empowering people “to have some command over how you think about yourself”, hers was a language that radically changed how Black women process their lives, Grundy said. “There is nothing that should be inaccessible about marginalized people being able to make thought of their own lives. That’s powerful.”

kihana miraya ross, a professor of African American studies at Northwestern University, said hooks’ writing had gripped her as a graduate student. “Her writing is so powerful and so important, but it’s also so clear. She has always been a role model for me in that way: no shade to people who don’t write like that, but I think that when you can say things clearly it means you understand what you’re saying.”

The accessibility of hooks’ words was exactly what Bullock Brown said she needed at a time when she felt all over the place.

“I didn’t really realize my value,” she said. “I didn’t recognize the issues that are specific to Black women and the ways that I was experiencing them. It was like a beautiful, really loving way to just kind of help me to begin to be centered and grounded in some reality and truth that may have taken me longer to really reconcile.”

Like me, Bullock Brown grew up in what I describe as “the remnant aura” of the civil rights movement in my book US Civil Rights Trail: A Traveler’s Guide to the People, Places, and Events that Made the Movement (2021). Surrounded by Black striving and excellence, there was a palpable energy that suggested to Black girls that it was up to us to make good on the opportunities won by that movement.

bell hooks remembered: ‘She embodied everything I wanted to be’

Read more

I’ve realized I grew up bound up in a sense of duty to excel but also a requirement to know my place. This surfaced in big and small ways, like on Sundays when my teen cousin, Reginald, would stop by for dinner, and my grandmother would order me to set a plate at the head of the table for him. I didn’t mind feeding him, but resisted the social programming to promote him to a place of honor simply because he was born male.

Similarly, Bullock Brown said she spent years unpacking the social messages to conform to specific, and limiting, ideas of what a woman is supposed to be – married with children – messages imparted in particular by her father.

“Part of the reason why I needed language is because there was a way my potential, my ability, even my own brilliance, to whatever extent that might exist, was muted because I’m a woman, because I was a girl,” she said. “A part of that experience was also not being encouraged to trust my own thoughts.”

A bespoke language created by hooks helped Bullock Brown learn, grow, and forgive. hooks matters because she helped so many of us Black women and girls to trust ourselves and articulate why.

“Our experiences as Black women and femmes is not going to be universal in the sense that we all go through the same thing; we’re not a monolith,” Bullock Brown said. “And yet, there’s a way that I think bell describes our experience that is both universal and specific.”

Deborah Douglas is the co-editor in chief of The Emancipator, a collaboration between Boston University and the Boston Globe, set to begin publishing original commentary in 2022

As we grieve bell hooks, let’s remember all that she taught us

Shanita Hubbard

The many of us whose writing is informed by her work will continue to use our words to fearlessly contend with white supremacy while never letting patriarchy off the hook

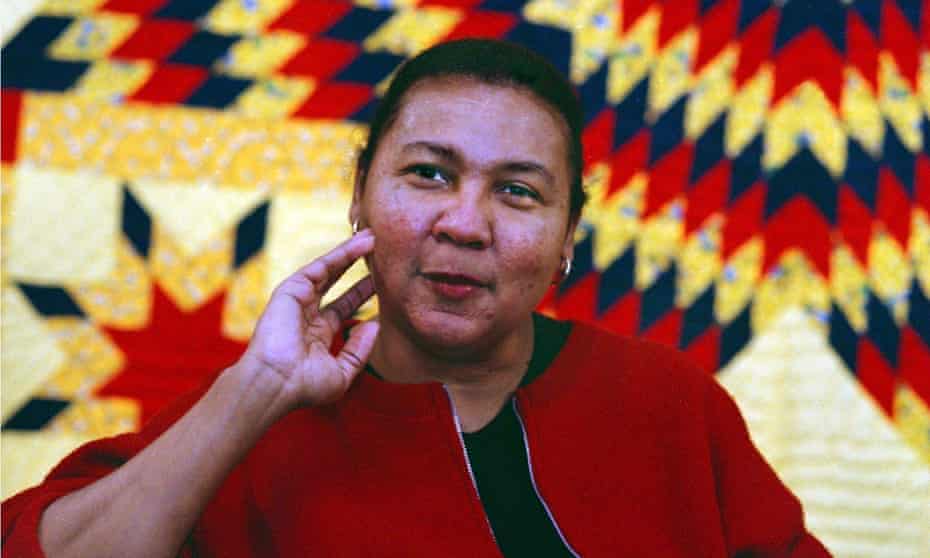

‘Even without meeting her, bell was our instructor.’

Photograph: The Washington Post/Getty Images

Thu 16 Dec 2021

On Wednesday, 15 December 2021 the world became a dimmer place. bell hooks, the brilliant, trailblazing author, cultural critic, feminist, poet and professor, died of an undisclosed illness. The news was first announced by her niece. I learned of it while scrolling social media. Before I could even digest what I had read, my phone exploded with texts from other Black women. I didn’t need to read them to know what they would state – I knew my sisters were hurting. We lost someone who transformed our thinking and gave us the language to challenge systems of oppression and the unique ways they harm Black women.

In her book Ain’t I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism, bell hooks brilliantly explores racism, feminism, class and patriarchy – or institutionalized sexism, as she called it. The book opens with a chapter tracing contemporary imagery of Black women in America back to the brutality of slavery. The book holds no punches; bell hooks explains how the suffrage movement excluded Black women and the ways that the civil rights movement didn’t always address the distinct needs of Black women. Like bell hooks herself, the work is complex and thought-provoking.

Aint I a Woman? was the first bell hooks book I read. I was in my final semester of graduate school at the time. At 23, I considered myself to be socially conscious. Prior to engaging with her work, I would wax poetic about injustice and the ways that systemic racism effectively launched weapons of mass destruction in my community. I would tell you that the “war on drugs” was nothing short of a war on Black men, and how the prison-industrial complex was another form of slavery. While the data indicates that there is a disproportionate number of Black men incarcerated, I failed to consider how these same systems of oppression also harmed Black women specifically. I did not have the range or language to even consider the ways in which race, class, and gender intersect and how this should frame my work and thinking around criminal justice reform. The more I studied her work the more I realized how much of my formal education left me with gaping holes in my thinking.

It was bell hooks who helped me understand that even when we talk about our collective freedom from racism this must also include fighting against sexism. Any fight against oppression that doesn’t include contending with sexism is not freedom at all – for Black women it’s merely an unspoken agreement to devalue an entire aspect of our personhood. This revelation started a radical transformation in me. I began to love my community differently. I developed a love for my community that wasn’t afraid to interrogate any narrative or practice that failed Black women. Because, as hooks’s work demonstrates, love without analysis is merely appreciation. She planted a seed that I’m still watering with her work.

bell hooks’s work shaped generations of Black women. Candice Marie Benbow, an essayist and the author of the forthcoming book Red Lip Theology, shared how bell hooks impacted her life. “bell hooks taught me that there is powerful specificity in my Black womanhood,” she told me. “That our lives require critical engagement and generous care. She loved us. When few loved Black women, she loved us well. She laid the blueprint so many of us are trying to follow. She was my teacher. I never met her but she taught me as well as she loved me. And, whenever I read her or listened to her, I felt it.”

Even without meeting her, bell was our instructor. She brilliantly theorized about radical love, healing and community in a way that caused us to consider unimaginable possibilities. Rhonda Nicole Tankerson, a singer-songwriter and digital marketing consultant, told me that she met bell through words. “bell hooks came later (in my 20s), as I began to explore Black feminists thought and scholarship. Her writings on love have been especially important in challenging my own understandings and expectations when it comes to seeking and experiencing it, romantically and otherwise. She made me dream of possibilities that I never knew could exist.”

bell hooks’s legacy consists of possibilities and reimagining love. This is especially true for Dr Jenn M Jackson, a writer and professor. “Her legacy, amongst other things, shows us that our work must be rooted in a deep love for our people and an unwavering commitment to holding grace for ourselves as we struggle,” they told me.

There is no single Black woman, cultural critic, feminist, poet, or professor among us that can carry bell hooks’s legacy alone. Nor can we heal from this loss alone. Fortunately, we don’t have to. She has already given us the blueprint for both. When we hurt over her death we will heal together as she taught us: “Rarely, if ever, are any of us healed in isolation. Healing is an act of communion.”

For the great many of us whose writing is informed by her work, we will continue to use our words to fearlessly contend with white supremacy while never letting patriarchy off the hook. This is a collective action and we are all needed. Because as bell hooks taught us, “No Black woman writer in this culture can write ‘too much’. Indeed, no woman writer can write ‘too much’ … No woman has ever written enough.”

Shanita Hubbard is an adjunct professor of sociology and the author of the forthcoming book Ride or Die: A Feminist Manifesto For The Well-Being of Black Women

thank you, bell hooks

The feminist icon, who has died aged 69, leaves behind a rich, powerful legacy

Anita Mureithi

16 December 2021, 4.57pm

bell hooks gave us the language and the courage to speak boldly about Blackness in an imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy |

Kevin Andre Elliott. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

There’s a quiet stillness that lingers in the air when you learn that someone you looked up to for years has passed, even if you never got to meet them. Yesterday, it felt like time stopped for a moment as the collective mind grappled with the sorrow of knowing that our time on earth with a legend had come to an end. bell hooks, or Gloria Jean Watkins was an inspiration. She always will be. A bestselling writer, feminist, poet and activist, who challenged us to think critically and look at the world through an intersectional lens. She changed people’s lives. She changed mine. There are generations of feminists who do not know who or what we would be without her teachings. She has guided us to live courageously and speak loudly.

I came across bell hooks’s ‘All About Love: New Visions’ during a tumultuous time. “When love is present the desire to dominate and exercise power cannot rule the day.” ‘All About Love’ invites us to define love beyond our ideas of what it is and what we think it looks like. It teaches us to challenge the prevailing cis normative, patriarchal notion that the nuclear family and romantic love are the most important expressions of love. It helps us think about love in a wider context, in terms of social justice, community and self-love. hooks said that “there can be no love without justice” and she emphasised that love is part of the journey to freedom; that truly living by a love ethic could bring about societal change.

On race, gender, politics and radical self-love, bell hooks shaped me into the woman and feminist that I am today, a sentiment that has been shared broadly by so many in the outpouring of love and gratitude on social media.

In ‘Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics’, hooks argued that “true resistance begins with people confronting pain… and wanting to do something to change it”. Her analysis of the importance of acknowledging and confronting the pain that we have experienced in order to move beyond it was powerful and still rings true today. The premise of theory as a place for deep transformation and healing on a personal and societal level led to a profound paradigm shift for me.

When I read her nuanced critique of white feminism in ‘Ain’t I a woman?: Black Women and Feminism’, I was entranced. “It is obvious that many women have appropriated feminism to serve their own ends, especially those white women who have been at the forefront of the movement; but rather than resigning myself to this appropriation I choose to re-appropriate the term ‘feminism’ to focus on the fact that to be a ‘feminist’ in any authentic sense of the term is to want for all people, female and male, liberation from sexist role patterns, domination, and oppression.” In the book, which is titled after a line in American abolitionist and activist Sojourner Truth’s 1851 speech in favour of women’s rights, hooks addressed the effects of the intersection of racism and sexism on Black women in ways that to this day, still resonate for so many of us. bell hooks was one of the leading intersectional feminists who made the critical connection between race, other marginalised identities, class, political history and feminism. She made feminist theory more inclusive and accessible for millions of people, including me.

She explained political theory in a way that made sense and found the words to describe the complex emotions that many of us often feel. For young, Black women trying to navigate hostile societies and find our place in the world, this was everything. She gave us the language and the courage to speak boldly about Blackness in an imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy. She had the ability to take a collective experience and articulate it in a way that made her work feel deeply personal. In ‘Remembered Rapture: The Writer At Work’, she said: “No Black woman writer in this culture can write ‘too much’. Indeed, no woman writer can write ‘too much’... No woman has ever written enough.” I have carried these words with me ever since I first read them.

No Black woman writer in this culture can write ‘too much’. Indeed, no woman writer can write ‘too much’... No woman has ever written enoughbell hooks

The beauty of hooks’s commentary was that while her analyses showed a fervent love for Black women, it was also universal in that everyone could learn from her literature, regardless of race, gender or sexual orientation. There are lessons in her teachings for each and every person.

Her work shows that there is a place for radical feminism in our everyday lives. From engagement within our communities to our personal relationships. In ‘Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics’, hooks says that: “To be truly visionary we have to root our imagination in our concrete reality while simultaneously imagining possibilities beyond that reality.”

What consoles us, as she takes her place with the ancestors, is the lifetime of work and wisdom that she has left behind. Even if, like every other woman, she didn’t write enough.

Feminism wouldn’t be what it is without the contributions of revolutionaries like bell hooks. May her teachings live on in our actions and in our words.

May she rest in love.

Thu 16 Dec 2021

Reni Eddo-Lodge. Photograph: Suki Dhanda/The Observer

Reni Eddo-Lodge: ‘When I tried to develop my own writing, I read hers’

British journalist and author of the bestselling Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race

It was bell hooks who planted the seed of a book in my brain. In a 2013 in-conversation event with Melissa Harris-Perry, she said she didn’t trust the internet, that a plug could be pulled at any time and that everything we put there could one day be lost. I was writing for the internet at the time – ephemeral articles that often got swept away on busy timelines. Hearing her musings persuaded me to slow down on putting my work online, and instead seek to put my political energy towards writing something physical that could be held and referred to, handed to someone, used as a tool.

But long before being influenced by her conversation with Melissa Harris-Perry, I had read her work voraciously. I first discovered it in my early 20s when I was navigating the whiteness of British feminism. Her writing wasn’t in print in Britain at the time, so PDFs of her work, such as Ain’t I a Woman, would circulate among activist groups. It served as a balm to those of us seeking refuge from white feminist hostility.

bell hooks in New York City, 1996.

Photograph: Karjean Levine/Getty Images

But her writing wasn’t only on feminist fractures. She was prolific, writing dozens of books across subjects – race, feminism, class, capitalism, masculinity, academia, children’s rights, spirituality and love. Her writing on love, in particular, served as a guiding light for me and so many others. Hers was an expansive analysis, with an intelligent feminist practice shining through, mooring those of us who had lost our way. Her first book was written when she was an undergraduate, but her entire body of work held an ancestral wisdom. She reminded feminist dissidents of the better world we were working towards.

When I tried to develop my own writing, I read hers. She embodied everything I wanted to be, writing with a compassion, care and clarity that I aspire to emulate in my own work.

Upon the news of her passing, I cried under my mask on a London bus, the gravity of her influence on me hitting like a gut punch. I wish I’d credited her more. But after the initial shock has subsided, I felt gratitude: for the work she’d given all of us and for it reaching me at the right time. For both of our times on this planet overlapping in such a way that I got to watch her holding court on a stage in New York from a box room in London. For the seed that was planted.

David Olusoga. Photograph: Karen Robinson/The Observer

David Olusoga: ‘She urged me to broaden my horizons’

British historian, broadcaster and author of Black and British: A Forgotten History

I met bell hooks just once. It was the early 2000s and I was producing a television documentary about how African Americans had, since civil rights, created a unique intellectual culture that had generated a great pantheon of black public intellectuals. hooks, one of the stars of that phenomenon, was inevitably one of the key interviewees. I can remember very little about my interview with her, carried out in a Manhattan brownstone belonging to one of her friends. But I remember a great deal about what happened next. After the interview we all went for drinks and the real questioning began. hooks interrogated me about my background, my education and above all my ambitions. She suggested books I should read, people I should meet and over a couple of hours was ceaselessly encouraging – as well as clever and funny.

She urged me, a young black TV producer she had only just met, to broaden my horizons and not limit my ideas of who I might become. Her urging was inflected with that sense of drive that highly educated African Americans so often possess and that Black Britons are so often in awe of. At a time in my life when the TV industry seemed so determined to assign me a pigeonhole and place limits on my expectations, her warmth and generosity was almost overwhelming. We finished our drinks, she smiled, wished me luck and was whisked away in an oversized American car, heading off to her next appointment. I always hoped I would see her again, but never did. To my shame I never got the chance to let her know how much our meeting had meant to me.

Jay Bernard.

Photograph: Alicia Canter/The Guardian

Jay Bernard: ‘She passed on the deceptively simple idea that to love is to think, and to think is to love’

Writer, artist and activist from London whose poetry about the New Cross Fire has won them the Ted Hughes Award and the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award

I first read bell hooks after I graduated from university, a very lost and depleted person. I moved to the other side of the world and found Teaching to Transgress and Teaching Community, which helped me begin to unlearn the problematic, and frankly racist, liberalism I had picked up during my degree. For me, bell hooks’ influence can be felt in that she passed on the deceptively simple idea that to love is to think, and to think is to love.

bell hooks during an interview for her book Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work in 1999. Photograph: The Washington Post/Getty Images

It is very difficult to put this into practice and her books hold nothing back in telling us to try. She is now done speaking. Whether we do it is entirely down to us.

Johny Pitts. Photograph: Antonio Olmos/The Observer

Johny Pitts: ‘She taught an entire generation that we weren’t there simply to be commodified’

British presenter, photographer and author of Jhalak prize-winning Afropean: Notes from Black Europe. He is the curator of The Eyes issue 12: The B-Side, which features black photographers and quotes from bell hooks

As well as focused rage, true activism involves innovation. bell hooks had it all, but it was particularly her outstanding interventions around the notion of the “oppositional gaze” that powered me up as a black writer and photographer. The idea that not only did I have the right to exist as a documentarian, but the very fact of my looking back was an act of resistance. She taught an entire generation that we weren’t there simply to be gawped at and commodified, but could – should – participate in the production of images.

Jeffrey Boakye. Photograph: Jeffrey Boakye

Jeffrey Boakye: ‘Her words will remain vital, stirring and rooted in compassion’

Author of Black, Listed: Black British Culture Explored and Hold Tight: Black Masculinity, Millennials and the Meaning of Grime

In times of such division and ideological polarisation, it feels like we need, more than ever before, the clarity of thought and passionate integrity that bell hooks so completely embodied in her work. Generations of thinkers owe a debt to her legacy of thought in areas of racism, feminism, marginality and their various intersections. Her words will remain vital, stirring and ultimately rooted in the soil of compassion. A salute to a towering figure of criticality, whose (lowercase) name is now synonymous with the most serious and incisive interrogations of who we are.

Margaret Atwood. Photograph: Jeremy Chan/Getty Images

Margaret Atwood: ‘Her dedication to the cause of ending “sexism, sexist exploitation and oppression” was exemplary’

Twice Booker-winning author of more than 50 books, including The Handmaid’s Tale, The Blind Assassin and The Testaments

bell hooks embodied amazing courage and deeply felt intelligence. In finding her own words and power, she inspired countless others to do the same. Her dedication to the cause of ending ‘sexism, sexist exploitation and oppression’ was exemplary.

Her impact extended far beyond the United States: many women from all over the world owe her a great debt.

Candice Carty-Williams. Photograph: Suki Dhanda/The Observer

Candice Carty-Williams: ‘The legacy she leaves behind is monumental and enduring’

British author of the bestselling novel Queenie. She won the book of the year the 2020 British Book Awards, becoming the first black woman to do so

bell hooks was a writer whose scope of sensibilities taught me, nourished me, engaged me. But it was her writing on love that changed my life after a friend forced me to read All About Love, a book that I knew would contain so much power and truth that I was afraid of its contents. bell hooks will be missed, but the legacy she leaves behind is monumental and enduring, much like the ideals of love she put to the page.

Aminatta Forna. Photograph: PR

Aminatta Forna: ‘She took care to put me at my ease’

Scottish and Sierra Leonean writer of the memoir The Devil That Danced on the Water and four novels: Ancestor Stones, The Memory of Love, The Hired Man and Happiness

I met bell hooks as a young reporter when I was sent to interview her for the BBC’s Late Show. This was back in the early 90s. She took care to put me at my ease, played music, made tea for us and complained about not being able to find anyone to braid her hair where she lived in Greenwich Village. In the ensuing interview she predicted the so-called “culture wars”, which I guess now, looking back, had already begun in the US. She said that one day the centre would have to shift. And she was right.

Photograph: Dominic Lipinski/PA

Afua Hirsch: ‘She exploded the false binary between the personal and the academic’

British journalist, former barrister and bestselling author of Brit(ish): On Race, Identity and Belonging

Reading bell hooks was an experience of profound relief. She had powerfully identified and articulated, with characteristic intellectual rigour, phenomena which I instinctively perceived but had never seen vocalised. Her writings on the crushing of black women’s sexual integrity, on the foundational racism of the “women’s movement”, and on the narratives that continue to divide and conquer black gender norms are searingly contemporary, in spite of the fact she began writing them decades ago.

And yet as a young black woman, it was bell’s generosity in sharing her own experience of love, sexuality and gender that provided the conduit for her work to reach me in such a personal and direct way. She exploded the false binary between the personal and the academic through her truth-telling, and it continues to inspire me to this day.