Women working as lab technicians in a factory in northern Afghanistan support their families as the country's economic crisis deepens [Kern Hendricks/Al Jazeera]

By Kern HendricksPublished On 19 Aug 2022Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan – Arzoo Noori holds two glass vials, carefully pouring a clear liquid from one to the other. As she holds one beaker up to the light of the window, swirling it slowly, the solution begins to turn a shade of translucent pink.In the high-ceilinged room behind her, Noori and six of her colleagues – all women clad in spotless white laboratory coats and latex gloves – make notes on clipboards, adjust bunsen burners, and handle antiquated-looking measuring devices. Amidst the delicate clinking of glassware and the scribble of pencils, the room has an air of calm, quiet productivity.Noori, aged 30, is a lab technician at Afghanistan’s largest chemical plant, located outside the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif in Balkh province. Slight of build and softly spoken, she exudes an air of confident professionalism as she moves between workbenches, deftly measuring out chemicals from bottles with peeling Russian labels.The factory, which produces urea fertiliser for Afghanistan’s agricultural sector, is a vestige of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989. Today the fertiliser comes packaged in freshly designed bags marked: Product of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. Towering above lush green fields, the factory smokestacks, cooling towers, and rusting industrial facades are a stark contrast to the simple, single-story mudbrick homes that dot the surrounding landscape.

The factory on the outskirts of Mazar-i-Sharif in Afghanistan’s north dates back to the Soviet occupation starting in the late 1970s [Kern Hendricks/Al Jazeera]

Noori began working at the factory when she was 23 years old after graduating with a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from Balkh University. She started as a lab assistant and quickly worked her way up to become manager of the entire urea production laboratory. It was a position that she studied hard for and was proud to earn.

Yet soon after the Taliban retook control of the country last August, Noori was stripped of her role and the female staff were separated from their male colleagues.

On an afternoon in March, Noori, engrossed in her work, is for the moment less interested in talking about these changes than in explaining the test that she and her colleagues are conducting.

“This is a test to assess the pH balance of the water we use here at the factory,” she says without looking up from the beaker in front of her. “It’s a simple task – we only have to add a few chemicals to the water – but if we don’t monitor the pH balance, other processes in the factory will be affected.” Noori – one of nearly 200 women working in the factory – takes immense pride in her work. She knows she is a vital part of the factory.

But now, working under the supervision of a man far less qualified than herself, Noori and many of her female colleagues wonder what the future holds for them – and for their careers – in the Taliban’s Afghanistan.

Settling ponds are used as part of the factory’s water purification process

[Kern Hendricks/Al Jazeera]

Changes to women’s jobsOne year since the Taliban regained full control of Afghanistan, the country remains in a fragile and impoverished state despite significant improvements to security.Climate change is wreaking havoc across the country – Afghanistan faces its worst drought in 27 years, and now has the highest level of emergency food insecurity of any nation on earth. A recent World Food Programme report projected that 22.8 million Afghans – roughly half of the country – faces severe food insecurity in 2022. Hundreds of thousands of families are now entirely reliant on the food provided by NGOs and the United Nations.Battered by the lasting effects of conflict, climate change, and international sanctions, Afghans also struggle to find any means of consistent income. Women have been hardest hit, with female employment expected to fall by 28 percent this year, according to the United Nations International Labour Organization.Against the backdrop of a humanitarian and economic crisis, the rights of Afghan women have also begun to erode. Many girls’ high schools around the country remain closed, locking thousands out of an education that seemed within their grasp only 12 months ago.Across the country, many women, particularly those working outside the healthcare and education sectors, have lost their jobs, and now find themselves unable to secure any form of employment. Some remain at home simply out of fear of interacting with the Taliban. Others continue to attend their jobs but find their workplaces are now gender-segregated. Demonstrations in support of women’s rights have, on several occasions, been violently repressed, and many women remain fearful that advocating for their rights will result in harassment, arrest, or worse.Noori and her colleagues at the factory live in one of Afghanistan’s least socially conservative cities and many of the women of Noori’s generation had some access to education and families who encouraged them to pursue their own careers as independent women. But when the Taliban returned to power in 2021, several of Noori’s older female colleagues worried that they might be barred from working at the state-owned plant.

Zia Omar has worked at the plant for 35 years. When the Taliban were previously in power, she was forced to stop working [Kern Hendricks/Al Jazeera]

Previous Taliban rule

Zia Omar, 50, has worked as a lab technician at the factory for 35 years. Like many women of her generation at the factory, she was hired and trained by the Soviets during their decade-long occupation. A gentle woman with a ready laugh, Omar wears a pink hijab draped loosely over her hair and shoulders. With decades of experience, she can easily hold a conversation as she carries out her tasks.

Omar says that she was forced to stop working under the previous Taliban government from 1996 to 2001. “They didn’t allow any women to work in the factory,” she says. “For almost six years I was stuck at home with no job.”

When her husband’s wage as an engineer at the factory proved too small to support the whole family, Omar decided she could contribute from home. She bought a sewing machine and spent the rest of the Taliban’s first rule tailoring clothes which her husband would then sell in the local bazaar.

After living and working through multiple upheavals and authorities, one thing is clear to Omar.

“I am tired of war,” she says, with a mix of sadness and anger. “I just want peace and stability for my country, I don’t think that’s too much to ask.”

Under the new Taliban government, the plant’s workplace at first stayed the same and men and women kept working alongside one another. “My male colleagues treated me like a sister or a daughter and everyone was very professional and respectful,” says Noori.

Bags of urea are filled at the urea plant in Balkh province.

The fertiliser is made from ammonia and carbon dioxide

[Kern Hendricks/Al Jazeera]

Then about three months after the Taliban retook the country, representatives from the Ministry for Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice came to the factory, Noori recalls.

At the mention of this infamous ministry – known for administering brutal punishments including lashings and beatings for playing music, watching films, and other “morality” infractions under the previous Taliban government – her colleagues in the lab exchange nervous glances, but Noori does not miss a beat.

“They said that it was not appropriate for a woman to be in charge of the lab, to be managing other staff,” says Noori softly. “So they removed me from my position as lab manager and installed a man instead. Technically he doesn’t have the same job title that I did, but practically he’s in charge now.”

Gender segregation was implemented across the offices and laboratories, preventing women from accessing some parts of the factory.

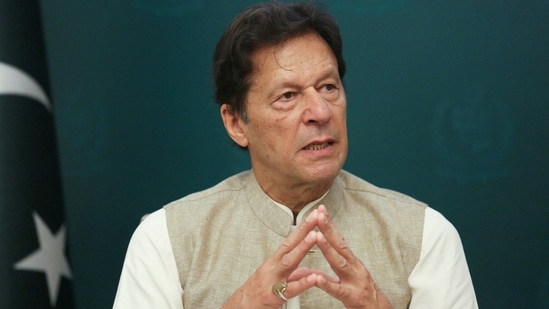

Arzoo Noori, aged 30, conducts a water-quality test in the lab where she was formerly a manager [Kern Hendricks/Al Jazeera]

‘That job is my right’

Although Noori’s work has remained largely the same – she still manages the day-to-day logistics of the lab – she no longer receives the pay or recognition she worked so hard to earn.

While Noori is frustrated by her downgraded role, it is her replacement’s qualifications – rather than his gender – that bothers her the most. “He’s a civil engineer, not a chemical engineer,” she says, throwing up her hands. “This is a chemical laboratory – he doesn’t have the right credentials. I have a degree in chemical engineering, and I sat special exams just to get that job. I earned it through hard work – that job is my right.” Working at their benches, the other women nod in agreement.

Earning less money also has serious repercussions in a country gripped by an economic crisis. Noori gestures out the window towards the city in the distance. “I’m responsible for all four members of my family,” she says. “My mother is dead, my father is retired, and my sister studies political science at university, so I’m the only one earning money for all of us.”

Under a programme implemented by the government headed by former President Ashraf Ghani, some skilled professionals and government employees were offered subsidised boosts to their monthly salary based on their level of higher education.

Noori says that when the Taliban took control of wage distribution for the factory workers, her bonuses disappeared. “Under the previous government, I used to receive a monthly bonus of 2,000 afghanis (about $22) because I graduated high school and also hold a bachelor’s degree,” she says.

Noori also worries that cuts to these bonuses remove incentives for the next generation of women to seek higher education. “If someone with no education earns the same as someone with a bachelor’s degree, why would anyone bother?”

Even though her wage is higher than most Afghans, things are still tight. “I used to earn 11,000 afghanis (about $124) per month, but now I only receive 9,000 afghanis ($100).” She turns her palms towards the sky. “That doesn’t go very far between five people. Food, clothing; we have to count every afghani now. And basic items are getting more expensive all the time.”

Shayma Momin been working at the factory for more than 35 years.

‘I’m proud to support my family with what I do,’ she says

[Kern Hendricks/Al Jazeera]

‘Focus on food and water’

Lab technician Shayma Momin, 52, furrows her brow as she delicately adjusts the dial on a Soviet-era pH meter, following the machine’s wavering indicator needle with concentration. As she spins the dial further, a few gold bracelets jangle at her wrist.

Momin has worked at the factory for more than 35 years, and, like Zia Omar was trained in her work by chemical engineers from the former USSR. She says that keeping her family afloat is an increasingly difficult task. Momin lives with her husband – a retired electrical engineer – along with two of her sons, her stepdaughter, and several grandchildren.

Momin is, like many of the other women at the factory, the sole earner for her household.

“My husband is retired, my daughters are married, and there is no one else to work except me,” she says. “My sons are graduated from university but they are jobless. One of my sons is married and has children but he is jobless too. It’s hard, but we survive.”

She says they do not buy new clothes, shoes or any “needless things”, adding that “we just focus on food and water.”

Momin’s husband, who used to work at the factory, used to receive a pension because of his decades of service. But now, under the new government, that is gone too, victim to cost-cutting measures.

Still, she remains optimistic. “People in Afghanistan are jobless right now,” she says, shaking her head. “I feel lucky to have my work here at the factory. It’s not easy, but I’m proud to support my family with what I do.”

Momin’s colleague Omar, is relieved about one change in particular.

“There was fighting between the previous government forces and the Taliban all around the factory, and our homes, for a long time,” she says.

“Even before the Taliban took control of the province, they had already taken control of this area. When they came, they took the area without violence,” she says, referring to the outskirts of the city where the factory is located. “I’m glad that the fighting is over now.”

Much of the lab equipment is a holdover from the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan

LONG PAST ITS BEST BEFORE DATE

[Kern Hendricks/Al Jazeera]

‘Many women have stopped’The women in the lab count themselves lucky to be able to continue working. But elsewhere in Afghanistan, others have not been so fortunate.Before last August, Razia Omar, 30, worked as a social activist promoting women’s rights and access to education in Qalat, the capital of Zabul province in Afghanistan’s southeast. She says once the Taliban entered the provincial government, the changes to women’s lives came swiftly.Razia says that because of Zabul’s inherent cultural conservatism, women were already more restricted than in other provinces. But when the Taliban arrived, public places became even more gender-segregated and new countrywide rules such as women only being able to travel with a male guardian were more strictly enforced in Zabul.She says she was scared by the new provincial government. “Mostly because of the uncertainty. We really didn’t know how they would act towards us, especially towards women,” says the mother of three young children in a soft voice.“Many women have stopped going to their offices here in Zabul,” she says, “Including me.” Razia stopped working last August, fearing that publicly advocating for women’s education would bring negative attention to her and her family.Those fears of a backlash have come to pass for other female activists. In January, following protests in Kabul, some activists had their homes raided. On August 13, a women’s rights march in Kabul was suppressed when Taliban fighters beat female protesters and began firing over their heads.But Razia says she still holds out hope for positive change. “Girls are still allowed to go to university here, so I’m hopeful that the government will also allow the girls to return to high school classes too. Luckily, I have already finished high school, but now I feel much more nervous about what the future holds for me, and especially my children,” she says. “I’m still hopeful that the government has the best interests of the Afghan people at heart, but I feel like I have been deprived of some of my rights and hopes for the future.”For Razia, jobs and educational opportunities are critical. “My family is in a bad economic situation now,” she says. “If they [the Taliban] could provide more jobs for women in government offices, it would help many families. We all need more work opportunities … the Taliban have made lots of promises about building this country up again, so I hope they will not let us down.”

Noori says believes in a brighter future and sees her field of chemical engineering as one that can help her country grow

[Kern Hendricks/Al Jazeera]

‘I want to help my country’

Back in the lab, Noori says that the situation for women at the factory is far from black and white.

“It’s true that some things in my life remained the same since the Taliban took power,” she says, adjusting the fabric around her face. “I’m still working now. I wore my chador in the same way as I do now. My sister still attends her university classes, although they’ve now been gender segregated.”

Noori says that she still believes in a brighter future.

“I want to complete my master’s and PhD and then come back to continue working in this factory,” she says, looking towards the city and the distant horizon. She points to the importance of manufacturing fertiliser for Afghanistan’s agricultural sector amidst the country’s widespread food insecurity. “Chemical engineering is an important field, and I want to help my country develop and grow,” she says.

“For now, my goal is to regain my old position and continue my work here.”

Noori looks up at the ageing wall clock on the laboratory wall. The afternoon is passing, and there is work to do. She begins to turn back to her tests but pauses for a moment.

“Things aren’t easy for women in Afghanistan – they have never been. I do what I can in my own life to follow my ambitions; that’s all I can do. I’d never marry a man who told me to stop my career, and I won’t let anyone else stop me either. I try to stay optimistic.”

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA