In Shawnee National Forest, a debate swirls around how to best protect trees amid climate change and wildfires

Chicago Tribune

2023/09/28

John Wallace, with Shawnee Forest Defense, examines harvested trees at the Bullwinkle timber sale of the Lee Mine project near Karbers Ridge on the eastern end of the Shawnee National Forest, Aug. 31, 2023.

The Shawnee National Forest in southern Illinois is a mosaic of towering trees, lush wetlands and commanding rock formations that are the native habitat for a wealth of plants and animals, including 19 species of oaks.

The forest is also a microcosm of an emergent national debate about how North America should manage public lands as wildfires burn through Canada, Hawaii and Louisiana. Climate change is catalyzing extreme weather events and drying ecosystems, making forests increasingly vulnerable.

“It’s impossible to take our hands all the way off. We’ve caused this climate change. We’ve introduced invasive species. We’ve put out historic wildfires. We’ve carved up the forest with roads. So, our influence on our forests is inescapable now,” said Chris Evans, a forest research specialist at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

But the U.S. Forest Service and environmentalists have opposing philosophies about how to tend to the Shawnee and other forests in the face of the climate crisis.

The Forest Service wants to take a more active role in encouraging woodland health and mitigating wildfire risk while many environmentalists want to create preserves where nature can heal itself.

The federal agency’s primary goal is to regenerate native ecosystems and increase biodiversity lost to poor farming practices and fire suppression dating back to the mid-19th century.

“If we don’t actively reintroduce disturbances using tools such as fire and timber harvest in this ecosystem, we will lose a community that is disproportionately important for wildlife,” said Michael Chaveas, forest supervisor of the Shawnee and the Hoosier National Forest in Indiana.

To encourage new tree growth, the Forest Service has invited timber companies to log parcels of both forests, a practice environmentalists in Illinois have encountered before.

In 1990, John Wallace left his career as a public land manager in Carbondale and dedicated his life to stopping commercial activity in the Shawnee. As part of a 79-day occupation of a logging site, he tethered himself to a log skidder with a bike lock. Authorities had to forcefully removehim with a blowtorch and arrested him. His protests eventually helped lead to a 17-year injunction on logging that was lifted in 2013.

Today, Wallace once again sees timber lorries driving into Illinois’ only national forest, and he has revived the fight to keep them out, this time with climate change front and center.

The mature oaks in the 289,000-acre forest must be left alone so they can optimally sequester carbon and the forest can naturally heal from human disturbances, according to Wallace and his allies at the Shawnee Park and Climate Alliance.

These environmentalists are campaigning to transfer oversight of the Shawnee from the Forest Service to the National Park Service, whose mission to preserve natural ecosystems puts a near-total ban on for-profit resource extraction.

Under the proposal, popular destinations such as Garden of the Gods would become a national park with the strictest land use regulations. The rest of the Shawnee would become the nation’s first preserve created to mitigate climate change. Public hunting, backcountry camping and other noncommercial recreational uses would be permitted, but trees would be left intact.

“Climate change is happening fast and we need to take drastic action. … We need to really protect and encourage natural ecosystems for their ability to sequester and store carbon,” Wallace said.

A climate preserve

Healthy forests offset greenhouse gases, which are the main driver of climate change, by absorbing more carbon than they release. All U.S. forests combined absorb more than 10% of annual domestic greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Biden administration.

However, whether forests are carbon sinks or emit carbon depends on how they are managed. Large, mature trees sequester the most carbon, trees release carbon when they are cut down and fires emit carbon.

The Alliance, which is supported by the cities of Carbondale and Murphysboro and the Illinois Audubon Society, is part of a growing movement to leave forests alone.

In Indiana, local opposition has mounted against Forest Service plans to ramp up logging and prescribed burning in the Hoosier forest. Last month in Oregon, a federal judge found a Trump-era rule change allowing large trees in the Pacific Northwest to be harvested violates several laws. And, a week ago, a coalition of 28 environmental groups sent the Forest Service a letter opposing a logging project in Wisconsin’s Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest, citing concerns that it does not align with the Biden administration’s latest environmental recommendations.

The Biden administration has recognized mature and old-growth forests as “critical carbon sinks.” In April, the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management created an initial inventory of these forests, following an executive order to protect them from climate change threats and enhance carbon sequestration.

The Alliance’s campaign builds on this movement by pushing to establish the first national preserve explicitly intended to safeguard mature trees to tap into their carbon sequestration potential. First, Congress would have to pass legislation to transfer the forest to the Park Service.

However, there is no consensus about how much primacy should be given to protect mature trees.

Forests are complex ecosystems and a sole focus on preserving older trees to optimize carbon sequestration is shortsighted, according to Eric Holzmueller, a forestry professor at Southern Illinois University. Trees are simultaneously dying and growing at different rates, and these rates change over time, making it difficult to project sequestration levels.

“It is a challenging puzzle in that there’s not a real clear answer. (Carbon sequestration) can be complicated and no one has really looked at the details of how the proposed management actions would either help the forest accumulate carbon or not,” he said.

Before determining whether and where to allow old trees to grow without disturbances, Holzmueller says more research must be done to determine how much carbon the Shawnee is currently storing and if parts of the forest are sequestering more than others.

Holzmueller also expressed concern that the Alliance is prioritizing carbon sequestration at the expense of promoting biodiversity and resilience to unpredictable natural disasters like storms, floods, invasive insect outbreaks and fires that could result in massive tree loss.

‘Huge fire risk issue’

Climate change demands that wildfires of unprecedented intensity be confronted in new places.

“These fires and the way that they are behaving right now are not going to be as extreme as they are going to be in the next decade. We have yet to see the full fruition of climate change come to light and how it’s going to influence wildfire behavior,” said Kimiko Barrett, lead wildfire researcher and policy analyst at nonprofit research group Headwaters Economics.

Though it does not have a history of large wildfires, southern Illinois is not excluded from this increased threat.

“We have a huge fire risk issue here, and just because we’re in a humid part of the world, we think that would never happen to us, but it can happen. Look around the country,” said Charles Ruffner, another professor of forestry at Southern Illinois University.

The unprecedented and devastating fires experienced in Canada, Maui and Louisiana this year were perpetuated by excessive heat and dryness.

The Forest Service uses prescribed burns to reduce flammable vegetation in the Shawnee, but the Alliance say these fires, combined with logging, are actually making the Shawnee drier and more fire-prone.

The Shawnee’s forest floor is naturally very moist, which has historically made it less vulnerable to large fires like those seen in the West. But, logging trees inevitably leaves behind leaf litter and fallen branches. It also opens the canopy, allowing more sunlight to reach the forest floor. The sun then dries out the leaves and branches that would decompose under natural moist conditions, creating prime fuel for fire.

While prescribed burns do reduce the fuel load, the first thing to grow back after a fire is herbaceous growth, which dies in the winter and becomes more fuel for fires.

While Ruffner and other local forestry experts acknowledge the potential for prescribed fires and logging to dry the forest floor, they say that a more likely and dangerous scenario is that the Midwest will experience a large drought.

“If we had a serious drought that lasted two to three years and killed a lot of that midstory, we would have communities that would lie in parallel to the same thing that we saw in Maui and Gatlinburg, Tennessee, in 2016 around the Great Smoky Mountains,” said Ruffner.

During a severe drought in 2016, wildfires burned more than 10,000 acres in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which has similar forest conditions to the Shawnee. More than 14,000 residents and tourists were forced to evacuate and more than 2,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed. In the deadliest fire in the United States in more than a century, at least 97 people were killed and 2,000 structures destroyed in August in Maui, where exceptionally high winds and dry conditions had been reported.

Over the last 10 years, the Forest Service has burned an average of 9,233 acres per year in the Shawnee to reduce fuel loads, with many acres being burned multiple times over a span of several years.

Ruffner said more burning is needed in strategically selected locations to thin the forest and remove understory brush.

Creating a climate preserve where trees are left intact is going to be counterproductive to mitigating the Shawnee’s “huge fire risk issue,” according to Ruffner.

Further, he and Barrett stressed that communities must not only think about how they manage their forests but also how they prepare their residents.

“People, communities and neighborhoods need to be better prepared for wildfires, but to do so requires a fundamental and significant upfront investment in how, where and under what conditions homes are placed in harm’s way,” Barrett said.

Since wildfires are uncommon, few communities in southern Illinois have community wildfire protection plans to mitigate fire risk. These plans would include practical measures like using fire resistant building materials, developing communications plans and thinning brush along highways to prevent fires from spreading onto the road.

Commercial interests

Throughout the Shawnee, swaths of barren land break up dense forest. On the edge of these logging sites, piles of trunks wait to be loaded onto timber lorries and taken to mills in Kentucky and Missouri. These lorries have overtaken roads that used to be dominated by hikers and horseback riders, according to Wallace.

When the injunction was lifted in 2013, 17,200 cubic feet of timber were harvested, or the equivalent volume of just under one-fifth of an Olympic-sized swimming pool, according to the Forest Service. In 2022, that figure had increased to 712,100 cubic feet, or the equivalent of eight Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Nested under the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Forest Service’s mission is to ensure forest “health, diversity and productivity.” It must balance the many benefits of the forest, including providing natural resources like timber.

“Storing carbon is one of many goals for a healthy, resilient forest,” Chaveas said.

But this mandate to make the forest hardy and profitable is inherently conflicting and not in the best interest of residents, members of the Alliance say.

The Forest Service gives contracts to the highest-bidding logging companies, many of which come from out of state.

Communities would see more benefit from the Shawnee if it were managed by the Park Service because the agency’s mission to preserve the forest for “enjoyment, education, and inspiration” would boost tourism, according to Alliance.

The economy in southern Illinois has historically centered on coal. As the industry declines, Murphysboro Mayor Will Stephens believes the creation of a national park and preserve could spark renewed interest in the region and revive the economy.

“We have to have a bias toward action in rural America, to try to find ways to make our communities vibrant and multidimensional so that when we go to market them in a regional or national way, people will make a decision to come see us instead of seeing somebody else,” he said.

In rural West Virginia, where the economy also suffered from the fall of coal, the establishment of the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve in 2020 brought in $96 million in economic impact in 2022, including more than 1,000 new jobs.

The Forest Service does not have an economic analysis of commercial logging, but Chaveas said “Southern Illinois clearly sees economic benefits from the projects on the forest.”

Even if the timber companies are not from Illinois, they hire loggers, equipment operators and truck drivers who are local. A portion of the timber sales also goes into the Secure Rural Schools Program, a federal program to maintain local schools and roads in areas where the tax base is limited by federal land.

Nevertheless, “maximizing revenue or focus on commercial interests do not factor into our decisions or actions,” Chaveas said.

Each harvest site is selectively chosen in the best interest of the forest, he said.

Restoring biodiversity

Restoring the Shawnee to its conditions pre-westward expansion is a priority for the Forest Service, according to its latest Forest Management Plan published in 2006.

“Our forests are not prepared for the shocks of climate change largely due to the legacy of land use,” Chaveas said.

When settlers arrived in the mid-19th century, they cleared large sections of the forest to plant corn, potatoes, wheat and oats. Over time, poor farming practices and over-logging made the soil infertile and southern Illinois entered a period of extreme economic decline.

The federal government established the Shawnee National Forest in 1933 in an effort to restore the forest and spur the depressed economy. However, the subsequent reforestation process happened relatively quickly, resulting in further loss of the native landscape.

Pines, which were introduced to control erosion, overtook native oaks in many areas. At the same time, suppression had become the dominant fire management strategy. Small, naturally occurring wildfires were extinguished before they could serve their ecological function of clearing the understory so sunlight could hit the forest floor.

Oaks need sunlight to grow so, over time, young oaks were replaced by maple and beech trees that thrive in shady conditions. Wildlife that find habitats in oaks suffered alongside the declining oak population.

Combined, the legacy of American settlement resulted in a forest that lacks diversity in age and composition.

“If you just let a forest kind of drive into a low diversity system that’s dominated by just a few species, there’s less species to adjust. Maintaining diversity as much as possible allows for more adaptation and more adjustment to climate change,” said Evans, the forestry specialist at U. of I.

By logging pines and mature oaks to open up the canopy and burning to clear the understory, the Forest Service says it is encouraging the growth of young oaks, which Chaveas points out are more efficient than mature trees at sequestering carbon.

However, even if they can sequester carbon at a faster rate, young trees have significantly less capacity to store carbon than older ones. The trees that are cut in the process also release carbon back into the atmosphere.

“It takes a forest that’s been cleared 10 to 30 years to regrow and become a carbon sink again. So, it’s giving up more carbon than it’s sequestering for 10 to 30 years and that’s no good. We don’t have time for that,” Wallace said.

Recent studies of the Shawnee and nearby deciduous forests also found that forest-clearing has not resulted in successful regeneration of oaks.

“The best way to regenerate oaks is to keep mature, acorn-producing oaks standing and not to use heavy equipment where young oaks can be found,” said Wallace, citing concerns that the machinery could damage young oaks.

The road ahead

The intense wildfires this summer forced the country to confront the delicate relationship between forests and worsening climate change.

The Chicago area experienced it intimately as smoke from Canada’s wildfires obscured the skyline on multiple days in June and July. On June 27, Chicago had the worst air quality of any major city in the world because of the fires, according to air quality monitoring site IQAir.

And those fires were over a thousand miles away.

As the Forest Service continues logging and burning projects in the Shawnee, the Alliance is crafting legislation. Members hope to introduce a bill to create Shawnee National Park and Climate Preserve on Capitol Hill by April 8, the date of the next total solar eclipse.

Crowds gathered in the Shawnee six years ago when it was deemed one of the best places to watch the Great American Eclipse of 2017.

“Everybody told me — all these visitors — ‘We had no idea this place is here. What a hidden gem! Who knew that the Shawnee was so special?’” Wallace recalled.

The forest is expected to be a prime location again for the 2024 eclipse, and this time, when visitors marvel at its beauty, he hopes it will inspire them to join the campaign to preserve it.

Ultimately, Alliance members realize that protecting the Shawnee alone will not result in enough carbon sequestration to make a significant dent in greenhouse gas emissions. But, they hope their campaign will inspire others to pursue similar efforts.

“It isn’t going to solve our climate problem, but taking the first step is always the most difficult one when it comes to change and the Shawnee is the perfect candidate,” Wallace said.

A tree marked to be harvested at a timber sale on the Waterfall Trail on the western end of the Shawnee National Forest near Murphysboro, Illinois, Aug. 30, 2023.

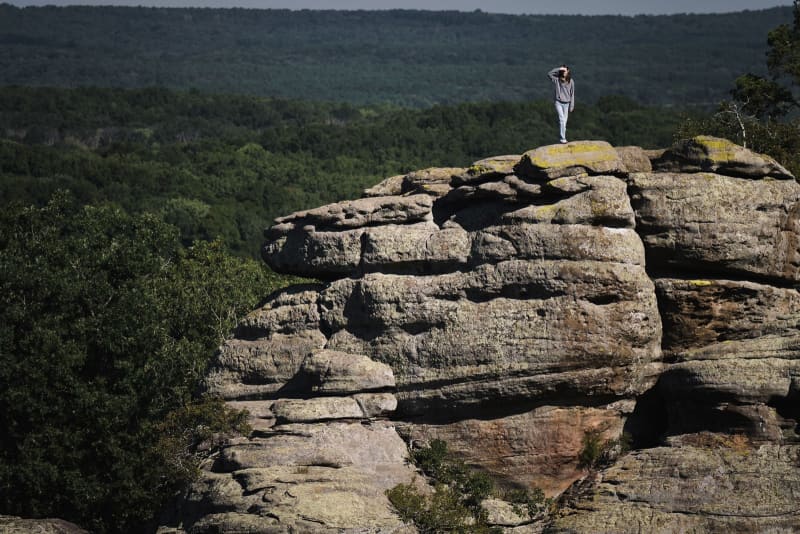

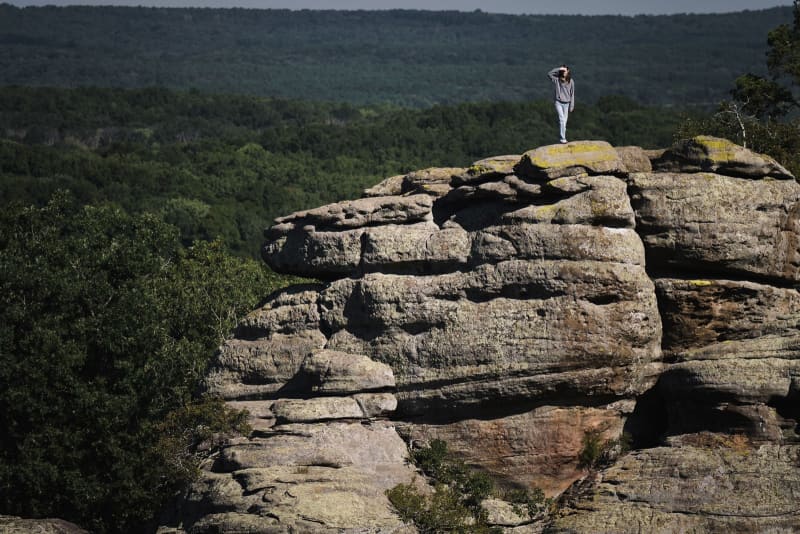

Garden of the Gods Wilderness area is framed by sandstone geologic structures on the eastern edge of the Shawnee National Forest, Aug. 31, 2023.

Visitors watch the sunset over the Mississippi River valley from LaRue Pine Hills Inspiration Point on the western edge of the Shawnee National Forest, Aug. 30, 2023

PHOTOS: E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune/TNS

© Chicago Tribune