No to the Russian-US plan to annex Ukraine!

Wednesday 21 May 2025, by Elias Vola, Gin Vola

The axe fell last week: the US announced its final proposal to ‘resolve’ Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. If rejected, it will withdraw from negotiations — meaning it will stop military support to Ukraine.

Unsurprisingly, the proposal echoes Moscow’s views and war aims. These include: US recognition of Crimea; maintaining the occupied territories under Russian control (i.e. 18.5% of Ukraine); lifting the sanctions imposed on Russia since 2014; US management of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant to supply electricity to Ukrainians and Russians; and strengthening economic cooperation between the US and... Russia.

As for Ukraine, summoned to comply with imperialist dictates, it would be forced to accept a colonial deal for the exploitation of its minerals, while no source of funding for its reconstruction has been proposed and security guarantees have been left to the Europeans.“”

Pressure on Ukraine at its peak

Zelensky took offence at this peace proposal, which is nothing more than a major violation of international law and an incitement to invade “small” countries around the world. Ukraine, supported by the Europeans, made a counter-proposal, rejecting the demilitarization of the country and any territorial concessions prior to discussions, and asking for details on security guarantees in the event of further aggression: the easing of sanctions should come after a genuine peace agreement.

In response, Trump lashed out at Zelensky, stating in particular that he “can have peace or fight for three more years and lose the whole country”. With the bombing of homes and civilian facilities in Ukrainian cities continuing unabated since the start of the negotiation process, pressure on Ukraine is at its peak. Last Sunday, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced that the withdrawal of the United States or the signing of an agreement would be finalized within the week.

The US withdrawal: what next?

While the signing of an agreement cannot be ruled out, it remains highly hypothetical. The Russian government’s lack of a clear position in the current situation suggests that it will continue to press its advantage by betting on a US military disengagement. On the Ukrainian side, everything will depend on its ability to continue to resist and therefore to rely on the support of European states that stand in solidarity with Ukraine.

If we want to avoid the worst-case scenario, namely Ukraine’s defeat and the strengthening of Russian neo-fascism, international solidarity must be stronger than ever.

For our part, together with our comrades on the ground and the Ukrainian resistance, we will continue to defend: ”The withdrawal of Russian troops. No annexations. The freedom to determine our future without external pressure. The right of return. Negotiations under democratic control. These are not magic formulas. They will not materialise by themselves,” as Oleksandr Kyselov, member of Sotsialnyi Rukh in Ukraine, declared at the February 2025 congress of the Fourth International.

5 May 2025

Translated by International Viewpoint from l’Anticapitaliste.

Attached documentsno-to-the-russian-us-plan-to-annex-ukraine_a9005.pdf (PDF - 905.1 KiB)

Extraction PDF [->article9005]

Elias Vola

Gin Vola

Gin Vola is a member of the NPA-A in France.

International Viewpoint is published under the responsibility of the Bureau of the Fourth International. Signed articles do not necessarily reflect editorial policy. Articles can be reprinted with acknowledgement, and a live link if possible.

‘Drill, baby, drill’: How the extraction and export of critical raw materials can exacerbate Ukraine’s resource trap

First published at Commons.

Interest in Ukraine’s mineral wealth has surged against the backdrop of global competition for critical raw materials needed for the transition to green energy and new technologies. This transition, presented as a path to sustainable development and the fight against climate change, is increasingly masking a fierce geopolitical struggle over resources, with various players striving to secure control over supply chains. Global attention is now particularly focused on the “mineral deal” between Ukraine and the United States, in which initial proposals by Donald Trump to exchange U.S. military aid for access to a significant portion of Ukraine’s mineral wealth exposed the cynical nature of this global race. The deal, framed as “minerals in exchange for weapons,” sparked heated debates about whether Ukraine truly possesses the quantity and quality of strategic minerals capable of justifying such astronomical expectations and the colonial ambitions of the new U.S. administration.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, the Ukrainian government intensified efforts to position resources such as lithium, titanium, graphite, and rare earth elements as strategic assets aimed at attracting foreign investors. The main goal is to channel these investments into post-war reconstruction, with a particular emphasis on a “private sector-led recovery,” which is to be coordinated by BlackRock — the world’s largest asset management company.

At the same time, it is well known that agreements based on the exploitation of natural resources rarely benefit the countries where these resources are located. This is demonstrated by the experience of many countries in Africa and Latin America.

The example of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is particularly revealing. In February 2024, the European Union and Rwanda signed a minerals agreement aimed at establishing a strategic partnership on critical raw materials such as tantalum, tin, tungsten, gold, and niobium. At the same time, it is well documented that the Rwanda-backed M23 rebel groups control mining areas in eastern DRC and smuggle minerals into Rwanda, which then enter global supply chains. These rebels are accused of serious human rights violations, including systematic sexual violence and war crimes. This spiral of violence has repeatedly sparked calls for the EU to end its raw materials agreement with Rwanda to avoid contributing to the further escalation of the conflict.

The global race for critical raw materials can provoke foreign interference and endanger the countries and communities that become targets of predatory extractivism. Bolivia, for example, has long been at the center of the global struggle for strategic mineral resources. Bolivian President Evo Morales nationalized the country’s vast natural resource reserves, including lithium, shortly after taking office in 2006. As part of plans to industrialize the lithium production chain, agreements were signed with China and Russia, providing for partnerships with the state-owned lithium company YLB, investments in local infrastructure, and technology transfer. Morales’s ousting from office in 2019 has been directly linked to his policy of lithium nationalization, which restricted access for Western foreign companies, including Tesla, and fostered closer ties with China and Russia. This predatory extractivism in the race for raw materials is epitomized by Elon Musk’s reaction to accusations that Tesla was involved in the coup in Bolivia: “We will coup whoever we want! Deal with it.”

Mining and the use of mineral resources are linked to about half of Ukraine’s industrial capacity and up to 20% of its labor force. In 2024, revenues from mineral exports accounted for only 8.1% of total exports. Compared to 2021, these figures have decreased by almost 60%. At the same time, Ukraine's experience with its own mineral resources — from coal, which powered Soviet industrialisation, to modern lithium, which is critical for the energy transition — shows a familiar pattern: both external and internal actors have historically sought to profit from this wealth, often undermining the country’s sovereignty and sustainable economic development.

This cycle of exploitation is sometimes viewed within the broader global dynamic associated with the so-called “resource curse” or “Dutch disease” — the paradox in which countries rich in natural resources often face economic instability, rising corruption, and abuse by foreign interests. “Dutch disease” typically arises when large inflows of foreign currency, mostly from raw material exports, lead to the strengthening of the national currency, making other export sectors less competitive and resulting in the decline of manufacturing or high value-added exports. At the same time, this perspective, which employs notions of “curse” and “nature,” tends to essentialize the colonial dynamic of systematically extracting resources from the periphery for the development of the center. The narrative of the “curse” of resource-rich countries portrays issues of dependency and inequality as inevitable, stemming from the mere fact of possessing resources. In doing so, it often overlooks the persistence of colonial power structures.

In the context of Ukraine’s integration into the EU, critical raw materials have become one of the topics of negotiations, especially as the EU seeks to ensure the continuity of supply chains for the energy transition and reduce its dependence on China. In 2021, within the framework of the Strategic Partnership between Ukraine and the EU on raw materials, Ukraine’s reserves of 22 out of 34 minerals critical to the EU were identified. Since then, cooperation has deepened: the European Union is offering a “win-win deal” aimed at promoting sustainable development and strategic partnership.

Resource trap: Ukraine’s economy and raw material exports

Ukraine is among the world’s leaders in reserves and production of key minerals, including iron ore, coal, manganese, titanium, graphite, and rare earth elements. This mineral wealth played a crucial role in the development of both the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. The exploitation of Ukraine’s deposits of coal, iron ore, manganese, and uranium was central to the industrialization and military strength of the USSR. Ukraine also historically played a key role in the production of titanium concentrates, providing 90% of total output in the former Soviet Union. Titanium concentrates are used as raw materials for producing titanium alloys and pigments, which are widely used in the aerospace, military, medical, and chemical industries. Interestingly, under martial law, Ukraine sold the state-owned United Mining and Chemical Company (UMCC), the country’s largest titanium ore producer. The company was established in 2014, when the state regained control of two key titanium enterprises previously owned by oligarch Dmytro Firtash. UMCC’s strategic goal was to shift from exporting raw materials to producing more technologically advanced products. However, despite its potential, the company did not modernize its production and remained a raw material exporter. The state ultimately failed to realize UMCC’s potential and lost control over this strategic asset: as a result of a privatization auction in October 2024, in which only one company participated, Azerbaijani businessman Nasib Hasanov became the new owner.

During the Soviet era, Ukraine produced a wide range of industrial goods and was a leading supplier of coal, cast iron, iron ore, and steel. However, it remained dependent on imports of high-precision components and technologies from other Soviet republics. Most Ukrainian manufacturers lacked complete production cycles, making cooperation with factories across the USSR costly. Instead of processing its own raw materials, Ukraine exported them to other republics for further production, reinforcing economic dependence and structural imbalances shaped by all-Union priorities rather than aligned with its own industrial development.

Since gaining independence in 1991, Ukraine’s export structure has remained predominantly oriented toward raw materials. Ukrainian industry continued to depend on inexpensive inputs, primarily energy from Russia, while exporting low-value-added products at higher world prices. However, instead of using the favorable terms of trade to diversify and modernize the economy, the additional profits were distributed among a narrow circle of elites, leading to the concentration of significant assets in the hands of a small group of oligarchs. By 2000, metals and mineral products accounted for half of Ukraine’s exports, and together with agri-food and chemical products, these sectors made up just over 70% of the country’s total exports.

Some studies point to Ukraine as an under-studied example of “Dutch disease” caused by excessive resource dependence. According to researchers, Ukraine’s over-reliance on steel and ferrous metals exports — accounting for nearly 30% of total exports — has led to a distorted economic structure characterized by deindustrialization, vulnerability to global commodity price fluctuations, and stagnation in high-tech production. They argue that Ukraine suffers from a variant of Dutch disease driven not by energy exports but by a commodity-based model that channels resources into rent-seeking and low-productivity sectors rather than innovation and manufacturing. When global prices for steel and ferrous metals rose, export revenues from the sector increased significantly, boosting demand for the hryvnia on foreign exchange markets and consequently strengthening the currency. This made Ukrainian goods more expensive for foreign buyers — a development that benefited steel exporters during the commodity markets boom but harmed other sectors, such as machine building and technology, whose products became less competitive abroad. At the same time, although Ukraine exhibits symptoms similar to Dutch disease — such as deindustrialization, the dominance of raw material exports, and weakness in high-tech sectors — it is worth noting that the decline of high-tech industries began earlier, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, when they were unable to compete globally. The severance of cooperative ties within the post-Soviet space, lack of investment, and loss of markets — especially after the 1998 financial crisis in Asia and Russia — accelerated the decline of Ukrainian producers. Ukraine’s commodity orientation thus became a forced adaptation rather than the result of crowding out caused by currency appreciation driven by raw material exports.

The global economic crisis of 2008 dealt a severe blow to the Ukrainian economy. The financial sector collapsed, exposing Ukraine’s critical dependence on raw materials, which had fueled growth in the early 2000s. The crisis also triggered a rapid decline in the remaining value-added industries that had failed to modernize: for example, the production of cars, buses, and tractors declined by 98%, 90%, and 77%, respectively, between 2007 and 2021. Ultimately, reliance on raw material exports created a vicious cycle in which economic growth remained tied to volatile global commodity markets, hindering the modernization of other sectors.

Today, Ukraine’s export structure continues to be dominated by raw materials and minimally processed products. However, while in 2008 metallurgical products accounted for 43.2% of Ukraine’s total export earnings, by the end of 2017 their share had decreased to 24.9%. This decline was primarily due to falling global steel prices, reduced competitiveness of Ukrainian steel on international markets, a significant drop in investment in the steel sector, and ultimately, the war. Today, the agricultural sector generates about half of Ukraine’s export revenues. In 2024, commodities made up more than 66% of Ukraine’s total exports, with agricultural raw materials, iron ore, and steel remaining the main sources of export income. The share of manufacturing in GDP is currently around 10%, just half the OECD benchmark.

Since independence, the Ukrainian economy has remained dependent on the export of raw materials with low levels of processing. This reliance has made Ukraine vulnerable to price fluctuations in global commodity markets, contributing to further deindustrialization and hindering the development of high-tech industries.

The geopolitics of Ukraine’s critical raw materials

Critical raw materials such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, rare earth elements, copper and silicon are indispensable for the manufacture of semiconductors, batteries and a wide range of high-tech devices. Their important role is particularly evident in the renewable energy sector. Rare earths are key to the production of permanent magnets, which are critical components of wind turbines and electric vehicle motors. At the same time, power grids require significant amounts of copper and aluminum, with copper being the base material for almost all electricity-related technologies.

The aggressive seizure of Ukraine’s natural resources constitutes a key element of Russia’s military strategy. The occupation of Ukrainian territories has enabled the Kremlin to establish control over vast reserves of critical minerals, energy resources, and agricultural land. It is not surprising that Russia has recently set a goal of completely eliminating its dependence on imports of critical raw materials by 2030. According to the head of Rosnedra, Evgeny Petrov, “As a result of a set of measures taken, by 2030 we expect to eliminate dependence on imports of 12 scarce raw materials, including lithium, niobium, tantalum, rare earth metals, zirconium, manganese, tungsten, molybdenum, rhenium, vanadium, fluorspar, and graphite. As for such a high-tech resource as lithium, we expect to achieve this by 2028.” Since 2014, and especially after the full-scale invasion in 2022, Russia has been systematically targeting lithium, titanium, rare earth elements, coal, oil, and gas deposits. Russia is already actively preparing for geological exploration of critical minerals in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine, particularly in the Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson regions. Russian media have paid special attention to the Shevchenkivske lithium deposit in Donetsk oblast and the Kruta Balka lithium deposit in Zaporizhzhia oblast. Ultimately, Russia’s control over Ukraine’s reserves will accelerate its expansion in global supply chains and significantly increase its pressure on the EU and other countries by consolidating control over critical raw materials. Russia’s ambitions are further bolstered by its deepening partnership with China. Russian commentators have discussed coordinating strategies on rare earth metals between Russia and China as a “common weapon” against Western influence and to control supply chains essential to advanced technologies. At the same time, Russia is actively developing cooperation with the countries of the Global South in the field of critical raw materials. For example, at the end of 2023, Bolivia and Russia announced a $450 million investment in a pilot project to produce lithium in Bolivia’s Uyuni salt flats. In turn, Rosatom is building a nuclear research and technology center in Bolivia.

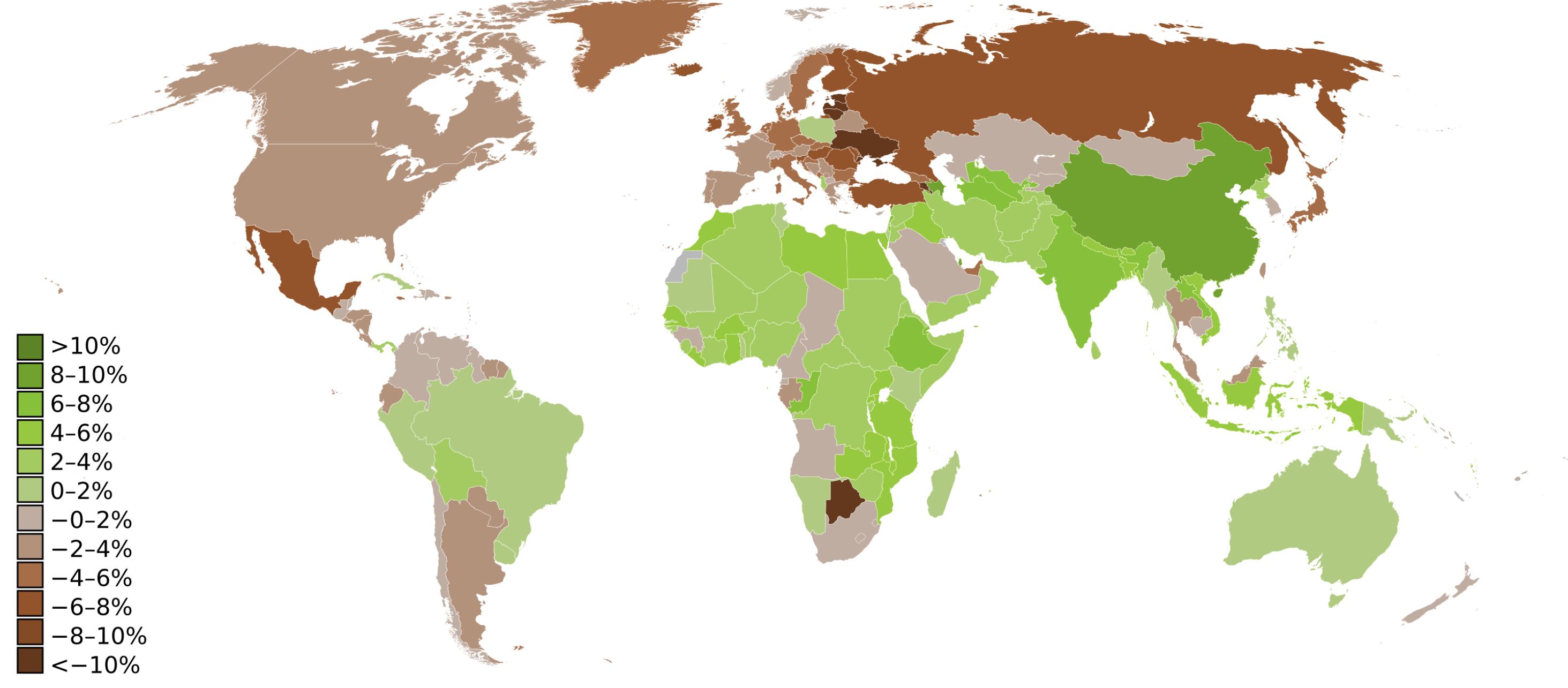

China holds a dominant position in the global supply chain for critical raw materials, including both their extraction and processing, such as copper, cobalt, lithium, graphite, and rare earths. For example, China accounts for almost 100% of the world’s spherical graphite processing, about 80% of gallium, approximately 60% of the refining of both lithium and germanium, and more than 60% of cobalt processing.

In light of China’s global dominance and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Ukrainian government has stepped up efforts to promote the country’s critical raw materials as a strategic asset to attract Western investment and support reconstruction after the war. Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal has stated that one of the government’s key priorities is developing a new economic model for Ukraine, with the goal of turning the country into a resource center for Europe. According to the Investment Guide of Ukraine, produced by the Kyiv School of Economics and the Ministry of Economy, Ukraine possesses 117 of the 120 most common types of minerals. The government also emphasizes that Ukraine is among the world’s top ten producers of several strategic minerals, including titanium, manganese, iron ore, zirconium, graphite, and uranium.

At the same time, the United States is pressuring Ukraine to accelerate the extraction and export of critical raw materials as part of its strategy to reduce US dependence on China. Since China accounts for over 70% of US imports of rare earths and has recently imposed export restrictions, any further restrictions could have serious consequences. In 2023 and 2024, China imposed export restrictions on gallium, germanium, graphite, and antimony, and in December 2024, it completely banned the supply of gallium, germanium, and antimony to the United States, citing national security. These measures were a response to restrictions imposed by the United States on the Chinese semiconductor sector. In response, Washington began to view Ukraine’s vast mineral reserves as an alternative to bolster national security. China’s export restrictions on cutting-edge processing technologies directly undermine the US and EU’s efforts to expand their industrial capacity in this area, as both sides actively seek advanced equipment and expertise. However, most of these high-tech solutions are concentrated in China, which is unsurprising given the four decades of investment. During this period, the US and EU not only reduced their production capacity but also significantly cut funding for research and development in the industry, putting them at a disadvantage. In recent years, the United States has been working to restore its role in the rare earths sector. The only rare earth mine in Mountain Pass, California, which had been out of operation for a long time, resumed production in 2017. However, until recently, the extracted raw materials were sent to China for processing.

Ukraine’s cooperation with the United States has become increasingly transactional since Donald Trump’s presidency, who framed access to Ukrainian resources as compensation for the billions of dollars in aid the United States provided during the war. Current negotiations are tense: Ukraine is seeking security guarantees, but the US approach mirrors Trump’s logic of seeking direct benefits from foreign investment while limiting China’s influence over critical supply chains. This strategy mirrors China’s “resources for infrastructure” model, including the 2007 Sicomines agreement in the Democratic Republic of Congo, under which China was to invest $3 billion in infrastructure in exchange for mining rights valued at $93 billion. While this provided the DRC with much-needed capital, the country later sought to renegotiate the deal, expressing concerns about not receiving a fair share of the benefits. Part of the promised infrastructure was not fully implemented or was constructed with poor quality. Meanwhile, profits from mining activities have mostly gone to Chinese companies, while the DRC has received a relatively small share of the actual income. The minerals agreement between the US and Ukraine risks perpetuating patterns of external control and unequal profit distribution, to the detriment of the resource-rich country. Such agreements may lead to higher project costs, as they often obligate governments to cooperate with specific companies without competitive tenders. Quality and control issues may arise, as contractors typically control project financing and implementation, limiting the government’s oversight ability. The complex, non-transparent structure increases the risk of mismanagement, and the lack of competition and the long-term nature of such agreements can create financial imbalances that benefit the investor over time. The agreement signed by Ukraine and the United States on April 30, 2025, grants the US near-exclusive access to new licenses for the extraction of minerals and critical raw materials — just as President Trump had sought. While the agreement does not require Ukraine to repay previous US assistance or transfer full ownership of resources, it also does not provide security guarantees from the United States.

The European Union is 100% dependent on China for all heavy rare earth elements — including dysprosium (magnets in electric vehicles and wind turbines), erbium (fiber-optic devices, lasers), lutetium (detectors, medical imaging), terbium (phosphors for displays), thulium (lasers, portable X-ray devices), and others — and 85% dependent on light rare earth elements, such as cerium (polishing materials), lanthanum (batteries, optical glass), neodymium (magnets, lasers, glass), praseodymium (alloys, magnets, glass), and samarium (magnets, nuclear reactors, glass). Although the EU’s reliance on China for other critical raw materials is slightly less severe, it remains significant. For example, China supplies 71% of the EU’s gallium imports, 97% of its magnesium, 40% of its natural graphite, and 62% of its vanadium. As a result of this dependence, the EU has increasingly set its sights on Ukraine in recent years as a potential supplier of critical raw materials.

Ukraine’s critical raw materials in the context of European integration

In July 2021, before the Russian invasion, the European Union and Ukraine signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) aimed at closer integration of value chains in the critical raw materials and battery sectors. Following the signing of the MoU, a roadmap was developed, outlining specific measures agreed upon by both parties to establish a strategic partnership. Notably, the instrument did not establish an independent body to monitor activities in this area. Public participation is not envisaged, while representatives from the economic and industrial sectors are prioritized. Overall, the wording of these documents remains rather vague. Although the EU expresses its intention to integrate Ukraine into the raw materials and battery value chain, the signed documents do not explicitly mention the production of final products directly in Ukraine.

In March 2023, the Ukrainian Government adopted the Law “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Improving Legislation in the Field of Subsoil Use,” aimed at deregulating the industry. Notably, it eliminates the need for approvals from local governments, the State Service of Geology and Mineral Resources, the State Labor Service, and other agencies for accessing subsoil, field development, water intake, and mining facility design. These changes, intended to attract investment and reduce administrative burdens on businesses, have effectively excluded communities from the decision-making process. The law also permits the issuance of special subsoil use permits without auction to companies that have conducted geological studies at their own expense. While this practice exists in other countries to stimulate investment, it often carries corruption risks: companies may conduct minimal research and subsequently acquire valuable assets without competition. The lack of independent verification of geological research results creates further opportunities for abuse. Additionally, as part of ongoing deregulation efforts, the Cabinet of Ministers adopted Resolution No. 749 on July 4, 2023, which removed the requirement to coordinate with the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources the sale of permits for sites where geological exploration has already been conducted. This issue is clearly exemplified by the case of the Makove Boloto (“Poppy Bog”) primeval forest natural monument in Rivne oblast, where a peat extraction permit was granted. The permit covered the entire area of the monument, which was officially established at the end of 2021, and effectively paved the way for its destruction, as peat extraction entails the complete removal of vegetation and topsoil. Similar cases have occurred in the Starovyzhivskyi nature reserve and near the Busha historical and cultural reserve.

Critical raw materials have become a dedicated section within the €50 billion Ukraine Facility instrument for the period from 2024 to 2027. According to Ukraine’s Plan under this instrument, the partnership with the EU aims to deepen the integration of value chains in the critical raw materials and battery sectors by developing Ukraine’s mineral resources based on a sustainable and socially responsible approach. At the same time, the sector is expected to be regulated according to EU standards, taking into account environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria, as well as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. However, the specific standards referenced by the government are not clarified. These international documents are voluntary and provide guidance for ethical business practices but do not carry the force of law unless they are incorporated into national legislation. Similarly, while the government refers to adherence to ESG principles, it does not specify which standards, metrics, or verification mechanisms will be applied. The ESG standards landscape itself is fragmented, with varying levels of ambition and enforcement. One of the reforms outlined in the Plan is the development of a study to assess the current legislation on environmental, social, and governance reporting in the mining sector. The fact that the government plans to “approve and publish the study” despite already implementing extensive deregulation measures in the sector clearly shows that ESG considerations were not systematically integrated into the initial reforms. Phrasing such as “gradual introduction of mandatory ESG reporting” and adherence to the “do no significant harm” principle — as far as possible under wartime or postwar reconstruction conditions — rather underscores a formal, EU-oriented approach to these commitments.

The adoption of the EU Critical Raw Materials Regulation in March 2024 will further strengthen the already established cooperation. In December 2024, the Ukrainian Parliament approved an updated National Program for the Development of the Mineral and Raw Materials Base of Ukraine for the Period Until 2030, which serves as one of the indicators of Ukraine’s implementation of the Ukraine Facility. The updated program defines the criteria for classifying mineral resources as strategically important. Overall, this law is oriented toward the broad expansion of large-scale extraction projects. Notably, in the section on peat, the law highlights that developing new peat deposits, requiring drainage,results in the loss of biospheric functions, increased environmental risks in the region, and the transformation of peatlands from carbon sinks into significant sources of greenhouse gas emissions. Although the document acknowledges the need to align peat extraction with the state’s climate and environmental policy, it does not outline practical mechanisms or guarantees to ensure such alignment. The law also provides for continued investment in hard coal deposits and the expansion of lignite (brown coal) extraction. At present, the National Program appears to contradict Ukraine’s National Energy and Climate Plan, which envisions a gradual phase-out of coal use in the electricity sector by 2035 in line with the goals of the European Green Deal.

The risks of the resource trap: Lessons we should have learned

The Ukrainian government’s proposal to use mineral resources as a tool for attracting international aid carries the risk of reproducing exploitative models typical of other resource-dependent countries. A focus on exporting critical raw materials to secure external support may deepen long-term dependence on foreign actors, undermining efforts to rebuild a self-sufficient, diversified economy. Excessive reliance on the export of critical raw materials could give foreign states leverage over Ukraine’s economic policy. A telling example is Ukraine’s dependence on Russian energy resources and their impact on Ukraine’s political and economic processes, especially when Russia used gas supplies as a tool of political pressure and economic blackmail, repeatedly attempting to take control of strategic infrastructure, including Ukraine’s gas transmission system.

The history of oligarchic control in Ukraine, particularly in sectors such as metallurgy and titanium production, where raw materials were exported instead of being processed domestically, shows how elite capture of resources and weak governance can divert mineral revenues from national reconstruction into private hands. This risks entrenching Ukraine’s role as a raw material supplier rather than transforming it into a producer of high value-added goods. Exporting raw materials also means missing opportunities to develop domestic manufacturing sectors — and with them, potential income and jobs.

At the same time, the exploration and extraction of critical raw materials are high-risk and capital-intensive projects, typically accessible only to a limited number of large corporations. Such mining initiatives require substantial upfront investments — ranging from 500,000 to 15 million euros per project — and involve lengthy and complex stages: geological exploration, feasibility studies, and obtaining operational permits. Bringing a mineral deposit into industrial production can take years and cost anywhere from 1 million to over 1 billion U.S. dollars, depending on the type of mine. Research indicates that, on average, it takes up to 16.5 years from the exploration phase to the start of production. Large Ukrainian business groups with access to capital are capable of participating in large-scale mining projects. However, their involvement raises serious concerns about transparency, the fair distribution of benefits, and the risk that profits from Ukraine’s critical resources may once again end up concentrated in the hands of a narrow group of individuals, rather than contributing to broad-based economic development and integration with the European Union.

Volatility in global raw material prices can also destabilize the Ukrainian economy. Ukraine’s experience as an exporter of ferrous metals clearly illustrates this risk. Over the past decade, Ukrainian iron and steel enterprises have been highly vulnerable to unpredictable fluctuations in global prices, directly affecting export volumes, company revenues, and the country’s balance of payments. Currently, supply chain disruptions caused by the war, stagnation of the domestic market, and increasingly unfavorable export conditions, including tariffs, are constraining the operations of Ukraine’s steel sector. According to industry representatives, steel production is expected to decline by 9% in 2025, with exports falling by 16%. Such dependence on raw material exports means that external market shocks can swiftly destabilize the economy, disrupt state budget revenues, and put jobs at risk.

Moreover, the extraction of critical raw materials poses significant environmental risks, such as substantial greenhouse gas emissions, water scarcity and pollution, land degradation, and loss of biodiversity. Water use poses an additional challenge, as many mines are located in regions already facing shortages, and extraction and processing activities often contaminate local water resources with toxic substances and heavy metals. The extraction of copper and lithium is particularly water-intensive, placing additional strain on already scarce water supplies. The physical expansion of mining areas leads to deforestation, soil erosion, and the destruction of natural habitats, threatening local biodiversity. Additionally, in the extraction of rare earth elements — even under the most favorable conditions — only about 2% of the extracted mass contains valuable materials, though concentrations can reach up to 20% in some deposits. These ores often also contain harmful impurities such as arsenic, thorium, fluorine, and uranium. For decades, significant amounts of these toxic byproducts have been released into the environment, spreading through air and water. As a result, pollutants have entered the food chain, and large-scale studies have linked exposure to serious long-term health effects, including developmental disorders in children, increased incidence of bone diseases, and other chronic illnesses.

Ultimately, while the government is focused entirely on involving the private sector in Ukraine’s reconstruction — prioritizing long-term critical raw material extraction projects — the country risks once again being trapped in the vicious cycle of serving as a raw material supplier for other economies.

Maryna Larina is a Graduate of the Free University of Berlin, and a researcher on climate and energy topics. Translation from Ukrainian: Pavlo Shopin.