"Racism and Science Fiction"

by Samuel R. Delany

From NYRSF Issue 120, August 1998. "Racism in SF" first appeared in volume form

in Darkmatter, edited by Sheree R. Thomas, Warner Books: New York, 2000.

Posted by Permission of Samuel R. Delany. Copyright © 1998 by Samuel R. Delany.

Racism for me has always appeared to be first and foremost a system, largely supported by material and economic conditions at work in a field of social traditions. Thus, though racism is always made manifest through individuals’ decisions, actions, words, and feelings, when we have the luxury of looking at it with the longer view (and we don’t, always), usually I don’t see much point in blaming people personally, white or black, for their feelings or even for their specific actions—as long as they remain this side of the criminal. These are not what stabilize the system. These are not what promote and reproduce the system. These are not the points where the most lasting changes can be introduced to alter the system.

For better or for worse, I am often spoken of as the first African-American science fiction writer. But I wear that originary label as uneasily as any writer has worn the label of science fiction itself. Among the ranks of what is often referred to as proto-science fiction, there are a number of black writers. M. P. Shiel, whose Purple Cloud and Lord of the Sea are still read, was a Creole with some African ancestry. Black leader Martin Delany (1812–1885—alas, no relation) wrote his single and highly imaginative novel, still to be found on the shelves of Barnes & Noble today, Blake, or The Huts of America (1857), about an imagined successful slave revolt in Cuba and the American South—which is about as close to an sf-style alternate history novel as you can get. Other black writers whose work certainly borders on science fiction include Sutton E. Griggs and his novel Imperio Imperium (1899) in which an African-American secret society conspires to found a separate black state by taking over Texas, and Edward Johnson, who, following Bellamy’s example in Looking Backward (1888), wrote Light Ahead for the Negro (1904), telling of a black man transported into a socialist United States in the far future. I believe I first heard Harlan Ellison make the point that we know of dozens upon dozens of early pulp writers only as names: They conducted their careers entirely by mail—in a field and during an era when pen-names were the rule rather than the exception. Among the “Remmington C. Scotts” and the “Frank P. Joneses” who litter the contents pages of the early pulps, we simply have no way of knowing if one, three, or seven or them—or even many more—were not blacks, Hispanics, women, native Americans, Asians, or whatever. Writing is like that.

Toward the end of the Harlem Renaissance, the black social critic George Schuyler (1895–1977) published an acidic satire Black No More: Being an Account of the Strange and Wonderful Workings of Science in the Land of the Free, A. D. 1933–1940 (The Macaulay Company, New York, 1931), which hinges on a three-day treatment costing fifty dollars through which black people can turn themselves white. The treatment involves “a formidable apparatus of sparkling nickel. It resembled a cross between a dentist chair and an electric chair.” The confusion this causes throughout racist America (as well as among black folks themselves) gives Schuyler a chance to satirize both white leaders and black. (Though W. E. B. Du Bois was himself lampooned by Schuyler as the aloof, money-hungry hypocrite Dr. Shakespeare Agamemnon Beard, Du Bois, in his column “The Browsing Reader” [in The Crisis, March ’31] called the novel “an extremely significant work” and “a rollicking, keen, good-natured criticism of the Negro problem in the United States” that was bound to be “abundantly misunderstood” because such was the fate of all satire.) The story follows the adventures of the dashing black Max Dasher and his sidekick Bunny, who become white and make their way through a world rendered topsy-turvy by the spreading racial ambiguity and deception. Toward the climax, the two white perpetrators of the system who have made themselves rich on the scheme are lynched by a group of whites (at a place called Happy Hill) who believe the two men are blacks in disguise. Though the term did not exist, here the “humor” becomes so “black” as to take on elements of inchoate American horror. For his scene, Schuyler simply used accounts of actual lynchings of black men at the time, with a few changes in wording:

The two men . . . were stripped naked, held down by husky and willing farm hands and their ears and genitals cut off with jackknives . . . Some wag sewed their ears to their backs and they were released to run . . . [but were immediately brought down with revolvers by the crowd] amidst the uproarious laughter of the congregation . . . [Still living, the two were bound together at a stake while] little boys and girls gaily gathered excelsior, scrap paper, twigs and small branches, while their proud parents fetched logs, boxes, kerosene . . . [Reverend McPhule said a prayer, the flames were lit, the victims screamed, and the] crowd whooped with glee and Reverend McPhule beamed with satisfaction . . . The odor of cooking meat permeated the clear, country air and many a nostril was guiltily distended . . . When the roasting was over, the more adventurous members of Rev. McPhule’s flock rushed to the stake and groped in the two bodies for skeletal souvenirs such as forefingers, toes and teeth. Proudly their pastor looked on (217–218).

Might this have been too much for the readers of Amazing and Astounding? As it does for many black folk today, such a tale, despite the ’30s pulp diction, has a special place for me. Among the family stories I grew up with, one was an account of a similar lynching of a cousin of mine from only a decade or so before the year Schuyler’s story is set. Even the racial ambiguity of Schuyler’s victims speaks to the story. A woman who looked white, my cousin was several months pregnant and traveling with her much darker husband when they were set upon by white men (because they believed the marriage was miscegenous) and lynched in a manner equally gruesome: Her husband’s body was similarly mutilated. And her child was no longer in her body when their corpses, as my father recounted the incident to me in the ’40s, were returned in a wagon to the campus of the black episcopal college where my grandparents were administrators. Hundreds on hundreds of such social murders were recorded in detail by witnesses and participants between the Civil War and the Second World War. Thousands on thousands more went unrecorded. (Billy the Kid claimed to have taken active part in a more than half a dozen such murders of “Mexicans, niggers, and injuns,” which were not even counted among his famous twenty-one adolescent killings.) But this is (just one of) the horrors from which racism arises—and where it can still all too easily go.

In 1936 and 1938, under the pen name “Samuel I. Brooks,” Schuyler had two long stories published in some 63 weekly installments in The Pittsburgh Courier, a black Pennsylvania newspaper, about a black organization, lead by a black Dr. Belsidus, who plots to take over the world—work that Schuyler considered “hokum and hack work of the purest vein.” Schuyler was known as an extreme political conservative, though the trajectory to that conservatism was very similar to Heinlein’s. (Unlike Heinlein’s, though, Schuyler’s view of science fiction was as conservative as anything about him.) Schuyler’s early socialist period was followed by a later conservatism that Schuyler himself, at least, felt in no way harbored any contradiction with his former principles, even though he joined the John Birch Society toward the start of the ’60s and wrote for its news organ American Opinion. His second Dr. Belsidus story remained unfinished, and the two were not collected in book form until 1991 (Black Empire, by George S. Schuyler, ed. by Robert A. Hill and Kent Rasmussen, Northeastern University Press, Boston), fourteen years after his death.

Since I began to publish in 1962, I have often been asked, by people of all colors, what my experience of racial prejudice in the science fiction field has been. Has it been nonexistent? By no means: It was definitely there. A child of the political protests of the ’50s and ’60s, I’ve frequently said to people who asked that question: As long as there are only one, two, or a handful of us, however, I presume in a field such as science fiction, where many of its writers come out of the liberal-Jewish tradition, prejudice will most likely remain a slight force—until, say, black writers start to number thirteen, fifteen, twenty percent of the total. At that point, where the competition might be perceived as having some economic heft, chances are we will have as much racism and prejudice here as in any other field.

We are still a long way away from such statistics.

But we are certainly moving closer.

After—briefly—being my student at the Clarion Science Fiction Writers’ Workshop, Octavia Butler entered the field with her first story, “Crossover,” in 1971 and her first novel, Patternmaster, in 1976—fourteen years after my own first novel appeared in winter of ’62. But she recounts her story with brio and insight. Everyone was very glad to see her! After several short story sales, Steven Barnes first came to general attention in 1981 with Dreampark and other collaborations with Larry Niven. Charles Saunders published his Imaro novels with DAW Books in the early ’80s. Even more recently in the collateral field of horror, Tannanarive Due has published The Between (1996) and My Soul to Keep (1997). Last year all of us except Charles were present at the first African-American Science Fiction Writers Conference sponsored by Clarke-Atlanta University. This year Toronto-based writer Nalo Hopkinson (another Clarion student whom I have the pleasure of being able to boast of as having also taught at Clarion) published her award-winning sf novel Brown Girl in the Ring (Warner, New York, 1998). Another black North American writer is Haitian-born Claude-Michel Prévost, a francophone writer who publishes out of Vancouver, British Columbia. Since people ask me regularly what examples of prejudice have I experienced in the science fiction field, I thought this might be the time to answer, then—with a tale.

With five days to go in my twenty-fourth year, on March 25, 1967, my sixth science fiction novel, Babel-17, won a Nebula Award (a tie, actually) from the Science Fiction Writers of America. That same day the first copies of my eighth, The Einstein Intersection, became available at my publishers’ office. (Because of publishing schedules, my seventh, Empire Star, had preceded the sixth into print the previous spring.) At home on my desk at the back of an apartment I shared on St. Mark’s Place, my ninth, Nova, was a little more than three months from completion.

On February 10, a month and a half before the March awards, in its partially completed state Nova had been purchased by Doubleday & Co. Three months after the awards banquet, in June, when it was done, with that first Nebula under my belt, I submitted Nova for serialization to the famous sf editor of Analog Magazine, John W. Campbell, Jr. Campbell rejected it, with a note and phone call to my agent explaining that he didn’t feel his readership would be able to relate to a black main character. That was one of my first direct encounters, as a professional writer, with the slippery and always commercialized form of liberal American prejudice: Campbell had nothing against my being black, you understand. (There reputedly exists a letter from him to horror writer Dean Koontz, from only a year or two later, in which Campbell argues in all seriousness that a technologically advanced black civilization is a social and a biological impossibility. . . .). No, perish the thought! Surely there was not a prejudiced bone in his body! It’s just that I had, by pure happenstance, chosen to write about someone whose mother was from Senegal (and whose father was from Norway), and it was the poor benighted readers, out there in America’s heartland, who, in 1967, would be too upset. . . .

It was all handled as though I’d just happened to have dressed my main character in a purple brocade dinner jacket. (In the phone call Campbell made it fairly clear that this was his only reason for rejecting the book. Otherwise, he rather liked it. . . .) Purple brocade just wasn’t big with the buyers that season. Sorry. . . .

Today if something like that happened, I would probably give the information to those people who feel it their job to make such things as widely known as possible. At the time, however, I swallowed it—a mark of both how the times, and I, have changed. I told myself I was too busy writing. The most profitable trajectory for a successful science fiction novel in those days was for an sf book to start life as a magazine serial, move on to hardcover publication, and finally be reprinted as a mass market paperback. If you were writing a novel a year (or, say, three novels every two years, which was then almost what I was averaging), that was the only way to push your annual income up, at the time, from four to five figures—and the low five figures at that. That was the point I began to realize I probably was not going to be able to make the kind of living (modest enough!) that, only a few months before, at the Awards Banquet, I’d let myself envision. The things I saw myself writing in the future, I already knew, were going to be more rather than less controversial. The percentage of purple brocade was only going to go up.

The second installment of my story here concerns the first time the word “Negro” was said to me, as a direct reference to my racial origins, by someone in the science-fiction community. Understand that, since the late ’30s, that community, that world had been largely Jewish, highly liberal, and with notable exceptions leaned well to the left. Even its right-wing mavens, Robert Heinlein or Poul Anderson (or, indeed, Campbell), would have far preferred to go to a leftist party and have a friendly argument with some smart socialists than actually to hang out with the right-wing and libertarian organizations which they may well have supported in principal and, in Heinlein’s case, with donations. April 14, 1968, a year and—perhaps—three weeks later, was the evening of the next Nebula Awards Banquet. A fortnight before, I had turned twenty-six. That year my eighth novel The Einstein Intersection (which had materialized as an object on the day of the previous year’s) and my short story, “Aye, and Gomorrah . . .” were both nominated.

In those days the Nebula banquet was a black tie affair with upwards of a hundred guests at a midtown hotel-restaurant. Quite incidentally, it was a time of upheaval and uncertainty in my personal life (which, I suspect, is tantamount to saying I was a twenty-six-year-old writer). But that evening my mother and sister and a friend, as well as my wife, were at my table. My novel won—and the presentation of the glittering Lucite trophy was followed by a discomforting speech from an eminent member of SFWA.

Perhaps you’ve heard such disgruntled talks: They begin, as did this one, “What I have to say tonight, many of you are not going to like . . .” and went on to castigate the organization for letting itself be taken in by (the phrase was, or was something very like) “pretentious literary nonsense,” unto granting it awards, and abandoning the old values of good, solid, craftsmanlike story-telling. My name was not mentioned, but it was evident I was (along with Roger Zelazny, not present) the prime target of this fusillade. It’s an odd experience, I must tell you, to accept an award from a hall full of people in tuxedos and evening gowns and then, from the same podium at which you accepted it, hear a half-hour jeremiad from an eminence gris declaring that award to be worthless and the people who voted it to you duped fools. It’s not paranoia: By count I caught more than a dozen sets of eyes sweeping between me and the speaker going on about the triviality of work such as mine and the foolishness of the hundred-plus writers who had voted for it.

As you might imagine, the applause was slight, uncomfortable, and scattered. There was more coughing and chair scraping than clapping. By the end of the speech, I was drenched with the tricklings of mortification and wondering what I’d done to deserve them. The master of ceremonies, Robert Silverberg, took the podium and said, “Well, I guess we’ve all been put in our place.” There was a bitter chuckle. And the next award was announced.

It again went to me—for my short story, “Aye, and Gomorrah . . .”. I had, by that time, forgotten it was in the running. For the second time that evening I got up and went to the podium to accept my trophy (it sits on a shelf above my desk about two feet away from me as I write), but, in dazzled embarrassment, it occurred to me as I was walking to the front of the hall that I must say something in my defense, though mistily I perceived it had best be as indirect as the attack. With my sweat soaked undershirt beneath my formal turtle-neck peeling and unpeeling from my back at each step, I took the podium and my second trophy of the evening. Into the microphone I said, as calmly as I could manage: “I write the novels and stories that I do and work on them as hard as I can to make them the best I can. That you’ve chosen to honor them—and twice in one night—is warming. Thank you.”

I received a standing ovation—though I was aware it was as much in reaction to the upbraiding of the nay-sayer as it was in support of anything I had done. I walked back down toward my seat, but as I passed one of the tables, a woman agent (not my own) who had several times written me and been supportive of my work, took my arm as I went by and pulled me down to say, “That was elegant, Chip . . . !” while the applause continued. At the same time, I felt a hand on my other sleeve—in the arm that held the Lucite block of the Nebula itself—and I turned to Isaac Asimov (whom I’d met for the first time at the banquet the year before), sitting on the other side and now pulling me toward him. With a large smile, wholly saturated with evident self-irony, he leaned toward me to say: “You know, Chip, we only voted you those awards because you’re Negro . . . !” (This was 1968; the term ‘black’ was not yet common parlance.) I smiled back (there was no possibility he had intended the remark in any way seriously—as anything other than an attempt to cut through the evening’s many tensions. . . . Still, part of me rolled my eyes silently to heaven and said: Do I really need to hear this right at this moment?) and returned to my table.

The way I read his statement then, and the way I read it today; indeed, anything else would be a historical misreading, is that Ike was trying to use a self-evidently tasteless absurdity (he was famous for them) to defuse some of the considerable anxiety in the hall that night; it is a standard male trope, needless to say. I think he was trying to say that race probably took little or no part in his or any other of the writer’s minds who had voted for me.

But such ironies cut in several directions. I don’t know whether Asimov realized he was saying this as well, but as an old historical materialist, if only as an afterthought, he must have realized that he was saying too: No one here will ever look at you, read a word your write, or consider you in any situation, no matter whether the roof is falling in or the money is pouring in, without saying to him- or herself (whether in an attempt to count it or to discount it), “Negro . . .” The racial situation, permeable as it might sometimes seem (and it is, yes, highly permeable), is nevertheless your total surround. Don’t you ever forget it . . . ! And I never have.

The fact that this particular “joke” emerged just then, at that most anxiety-torn moment, when the only-three-year-old, volatile organization of feisty science fiction writers saw itself under a virulent battering from internal conflicts over shifting aesthetic values, meant that, though the word had not yet been said to me or written about me till then (and, from then on, it was, interestingly, written regularly, though I did not in any way change my own self presentation: Judy Merril had already referred to me in print as “a handsome Negro.” James Blish would soon write of me as “a merry Negro.” I mean, can you imagine anyone at the same time writing of “a merry Jew”?), it had clearly inhered in every step and stage of my then just-six years as a professional writer.

Here the story takes a sanguine turn.

The man who’d made the speech had apparently not yet actually read my nominated novel when he wrote his talk. He had merely had it described to him by a friend, a notoriously eccentric reader, who had fulminated that the work was clearly and obviously beneath consideration as a serious science fiction novel: Each chapter began with a set of quotes from literary texts that had nothing to do with science at all! Our naysayer had gone along with this evaluation, at least as far as putting together his rubarbative speech.

When, a week or two later, he decided to read the book for himself (in case he was challenged on specifics), he found, to his surprise, he liked it—and, from what embarrassment I can only guess, became one of my staunchest and most articulate supporters, as an editor and a critic. (A lesson about reading here: Do your share, and you can save yourself and others a lot of embarrassment.) And Nova, after its Doubleday appearance in ’68 and some pretty stunning reviews, garnered what was then a record advance for an sf novel paid to date by Bantam Books (a record broken shortly thereafter), ushering in the twenty years when I could actually support myself (almost) by writing alone.

(Algis Budrys, who also had been there that evening, wrote in his January ’69 review in Galaxy, “Samuel R. Delany, right now, as of this book, Nova, not as of some future book or some accumulated body of work, is the best science fiction writer in the world, at a time when competition for that status is intense. I don’t see how a science fiction writer can do more than wring your heart while telling you how it works. No writer can. . . .” Even then I knew enough not to take such hyperbole seriously. I mention it to suggest the pressures around against which one had to keep one’s head straight—and, yes, to brag just a little. But it’s that desire to have it both ways—to realize it’s meaningless, but to take some straited pleasure nevertheless from the fact that, at least, somebody was inspired to say it—that defines the field in which the dangerous slippages in your reality picture start, slippages that lead to that monstrous and insufferable egotism so ugly in so many much-praised artists.)

But what Asimov’s quip also tells us is that, for any black artist (and you’ll forgive me if I stick to the nomenclature of my young manhood, that my friends and contemporaries, appropriating it from Dr. Du Bois, fought to set in place, breaking into libraries through the summer of ’68 and taking down the signs saying Negro Literature and replacing them with signs saying “black literature”—the small “b” on “black” is a very significant letter, an attempt to ironize and de-transcendentalize the whole concept of race, to render it provisional and contingent, a significance that many young people today, white and black, who lackadaisically capitalize it, have lost track of), the concept of race informed everything about me, so that it could surface—and did surface—precisely at those moments of highest anxiety, a manifesting brought about precisely by the white gaze, if you will, whenever it turned, discommoded for whatever reason, in my direction. Some have asked if I perceived my entrance into science fiction as a transgression.

Certainly not at the entrance point, in any way. But it’s clear from my story, I hope (and I have told many others about that fraught evening), transgression inheres, however unarticulated, in every aspect of the black writer’s career in America. That it emerged in such a charged moment is, if anything, only to be expected in such a society as ours. How could it be otherwise?

A question that I am asked nowhere near as frequently—and the recounting of tales such as the above tends to obviate and, as it were, put to sleep—is the question: If that was the first time you were aware of direct racism, when is the last time?

To live in the United States as a black man or woman, the fact is the answer to that question is rarely other than: A few hours ago, a few days, a few weeks . . . So, my hypothetical interlocutor persists, when is the last time you were aware of racism in the science fiction field per se. Well, I would have to say, last weekend I just spent attending Readercon 10, a fine and rich convention of concerned and alert people, a wonderful and stimulating convocation of high level panels and quality programming, with, this year, almost a hundred professionals, some dozen of whom were editors and the rest of whom were writers.

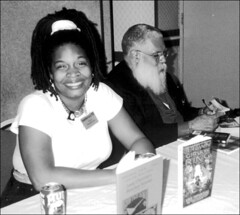

In the Dealers’ room was an Autograph Table where, throughout the convention, pairs of writers were assigned an hour each to make themselves available for book signing. The hours the writers would be at the table was part of the program. At 12:30 on Saturday I came to sit down just as Nalo Hopkinson came to join me.

In the Dealers’ room was an Autograph Table where, throughout the convention, pairs of writers were assigned an hour each to make themselves available for book signing. The hours the writers would be at the table was part of the program. At 12:30 on Saturday I came to sit down just as Nalo Hopkinson came to join me.

Understand, on a personal level, I could not be more delighted to be signing with Nalo. She is charming, talented, and I think of her as a friend. We both enjoyed our hour together. That is not in question. After our hour was up, however, and we went and had some lunch together with her friend David, we both found ourselves more amused than not that the two black American sf writers at Readercon, out of nearly eighty professionals, had ended up at the autograph table in the same hour. Let me repeat: I don’t think you can have racism as a positive system until you have that socio-economic support suggested by that (rather arbitrary) twenty percent/eighty percent proportion. But what racism as a system does is isolate and segregate the people of one race, or group, or ethnos from another. As a system it can be fueled by chance as much as by hostility or by the best of intentions. (“I thought they would be more comfortable together. I thought they would want to be with each other . . .”) And certainly one of its strongest manifestations is as a socio-visual system in which people become used to always seeing blacks with other blacks and so—because people are used to it—being uncomfortable whenever they see blacks mixed in, at whatever proportion, with whites.

My friend of a decade’s standing, Eric Van, had charge at this year’s Readercon of the programming the coffee klatches, readings, and autograph sessions. One of the goals—facilitated by computer—was not only to assign the visiting writers to the panels they wanted to be on, but to try, when possible, not to schedule those panels when other panels the same writers wanted to hear were also scheduled. This made some tight windows. I called Eric after the con, who kindly pulled up grids and schedule sheets on his computer. “Well,” he said, “lots of writers, of course, asked to sign together. But certainly neither you nor Nalo did that. As I recall, Nalo had a particularly tight schedule. She wasn’t arriving until late Friday night. Saturday at 12:30 was pretty much the only time she could sign—so, of the two of you, she was scheduled first. When I consulted the grid, the first two names that came up who were free at the same time were you and Jonathan Lethem. You came first in the alphabet—and so I put you down. I remember looking at the two of you, you and Nalo, and saying: Well, certainly there’s nothing wrong with that pairing. But the point is, I wasn’t thinking along racial lines. I probably should have been more sensitive to the possible racial implications—”

Let me reiterate: Racism is a system. As such, it is fueled as much by chance as by hostile intentions and equally the best intentions as well. It is whatever systematically acclimates people, of all colors, to become comfortable with the isolation and segregation of the races, on a visual, social, or economic level—which in turn supports and is supported by socio-economic discrimination. Because it is a system, however, I believe personal guilt is almost never the proper response in such a situation. Certainly, personal guilt will never replace a bit of well-founded systems analysis. And one does not have to be a particularly inventive science fiction writer to see a time, when we are much closer to that 20 percent division, where we black writers all hang out together, sign our books together, have our separate tracks of programming, if we don’t have our own segregated conventions, till we just never bother to show up at yours because we make you uncomfortable and you don’t really want us; and you make us feel the same way . . .

One fact that adds its own shadowing to the discussion is the attention that has devolved on Octavia Butler since her most deserved 1995 receipt of a MacArthur “genius” award. But the interest has largely been articulated in terms of interest in “African-American Science Fiction,” whether it be among the halls of MIT, where Butler and I appeared last, or the University of Chicago, where we are scheduled to appear together in a few months. Now Butler is a gracious, intelligent, and wonderfully impressive writer. But if she were a jot less great-hearted than she is, she might very well wonder: “Why, when you invite me, do you always invite that guy, Delany?”

The fact is, while it is always a personal pleasure to appear with her, Butler and I are very different writers, interested in very different things. And because I am the one who benefits by this highly artificial generalization of the literary interest in Butler’s work into this in-many-ways-artificial interest in African-American science fiction (I’m not the one who won the MacArthur, after all), I think it’s incumbent upon me to be the one publicly to question it. And while it provides generous honoraria for us both, I think that the nature of the generalization (since we have an extraordinarily talented black woman sf writer, why don’t we generalize that interest to all black sf writers, male and female) has elements of both racism and sexism about it.

One other thing allows me to question it in this manner. When, last year, there was an African-American Science Fiction Conference at Clark-Atlanta University, where, with Steve Barnes and Tanananarive Due, Butler and I met with each other, talked and exchanged conversation and ideas, spoke and interacted with the university students and teachers and the other writers in that historic black university, all of us present had the kind of rich and lively experience that was much more likely to forge common interests and that, indeed, at a later date could easily leave shared themes in our subsequent work. This aware and vital meeting to respond specifically to black youth in Atlanta is not, however, what usually occurs at an academic presentation in a largely white University doing an evening on African-American sf. Butler and I, born and raised on opposite sides of the country, half a dozen years apart, share many of the experiences of racial exclusion and the familial and social responses to that exclusion which constitute a race. But as long a racism functions as a system, it is still fueled from aspects of the perfectly laudable desires of interested whites to observe this thing, however dubious its reality, that exists largely by means of its having been named: African-American science fiction.

To pose a comparison of some heft:

In the days of cyberpunk, I was often cited by both the writers involved and the critics writing about them as an influence. As a critic, several times I wrote about the cyberpunk writers. And Bill Gibson wrote a gracious and appreciative introduction to the 1996 reprint of my novel Dhalgren. Thus you might think that there were a fair number of reasons for me to appear on panels with those writers or to be involved in programs with them. With all the attention that has come on her in the last years, Butler has been careful (and accurate) in not claiming that I am any sort of influence on her. I have never written specifically about her work. Nor, as far as I know, has she ever mentioned me in print.

Nevertheless: Throughout all of cyberpunk’s active history, I only recall being asked to sit on one cyberpunk panel with Bill, and that was largely a media-focused event at the Kennedy Center. In the last ten years, however, I have been invited to appear with Octavia at least six times, with another appearance scheduled in a few months and a joint interview with the both of us scheduled for a national magazine. All the comparison points out is the pure and unmitigated strength of the discourse of race in our country vis-à-vis any other. In a society such as ours, the discourse of race is so involved and embraided with the discourse of racism that I would defy anyone ultimately and authoritatively to distinguish them in any absolute manner once and for all.

Well, then, how does one combat racism in science fiction, even in such a nascent form as it might be fibrillating, here and there. The best way is to build a certain social vigilance into the system—and that means into conventions such as Readercon: Certainly racism in its current and sometimes difficult form becomes a good topic for panels. Because race is a touchy subject, in situations such as the above mentioned Readercon autographing session where chance and propinquity alone threw blacks together, you simply ask: Is this all right, or are there other people that, in this case, you would rather be paired with for whatever reason—even if that reason is only for breaking up the appearance of possible racism; since the appearance of possible racism can be just as much a factor in reproducing and promoting racism as anything else: Racism is as much about accustoming people to becoming used to certain racial configurations so that they are specifically not used to others, as it is about anything else. Indeed, we have to remember that what we are combatting is called prejudice: prejudice is pre-judgment—in this case, the prejudgment that the way things just happen to fall out are “all right,” when there well may be reasons for setting them up otherwise. Editors and writers need to be alerted to the socio-economic pressure on such gathering social groups to reproduce inside a new system by the virtue of “outside pressures.” Because we still live in a racist society, the only way to combat it in any systematic way is to establish—and repeatedly revamp—anti-racist institutions and traditions. That means actively encouraging the attendance of nonwhite readers and writers at conventions. It means actively presenting nonwhite writers with a forum to discuss precisely these problems in the con programming. (It seems absurd to have to point out that racism is by no means exhausted simply by black/white differences: indeed, one might argue that it is only touched on here.) And it means encouraging dialogue among, and encouraging intermixing with, the many sorts of writers who make up the sf community.

It means supporting those traditions.

I’ve already started discussing this with Eric. I will be going on to speak about it with the next year’s programmers.

Readercon is certainly as good a place as any, not to start but to continue.