MSM

Analysis

Since returning to office, US President Donald Trump has signed executive orders stripping more than a million federal workers of their right to collective bargaining – a move that unions warn likely heralds a similar assault on workers employed in the private sector.

Issued on: 04/09/2025 -

FRANCE24

By: Paul MILLAR

People participate in the Labor Day Workers Over Billionaires rally in solidarity with unions and advocacy groups on September 1, 2025 in Chicago, Illinois.

© Audrey Richardson, Getty Images via AFP

The chainsaw is back up and roaring. In August alone, more than 445,000 federal employees were stripped of their collective bargaining rights as government agencies followed twin executive orders from US President Donald Trump removing union protections from more than a million public-sector workers. The second order was signed on August 28, just days before US workers took to the streets to march in the country’s annual Labor Day parades.

For many of the hundreds of thousands of federal workers targeted by the move, their unions will no longer be able to fight back against contract violations committed by the agencies, and the employees themselves could lose hard-won benefits around parental leave and rest periods. While the orders are still before the courts, nine federal agencies, including the Department of Veterans' Affairs, have already terminated union contracts covering just shy of half a million workers.

The executive orders, which mark the largest removal of union protections in US history, draw upon decades-old presidential powers to deny federal workers the right to collective bargaining on national security grounds.

In the past, this power has been used sparingly to restrict collective bargaining rights among certain employees working for US intelligence agencies such as the CIA or the National Security Agency.

The new orders extend this logic to employees at more than two dozen government agencies, including the departments of Veterans’ Affairs, Agriculture, Health and Human Services, the Patent Office and the Environmental Protection Agency. Law enforcement services such as the police were explicitly left out of the orders.

The chainsaw is back up and roaring. In August alone, more than 445,000 federal employees were stripped of their collective bargaining rights as government agencies followed twin executive orders from US President Donald Trump removing union protections from more than a million public-sector workers. The second order was signed on August 28, just days before US workers took to the streets to march in the country’s annual Labor Day parades.

For many of the hundreds of thousands of federal workers targeted by the move, their unions will no longer be able to fight back against contract violations committed by the agencies, and the employees themselves could lose hard-won benefits around parental leave and rest periods. While the orders are still before the courts, nine federal agencies, including the Department of Veterans' Affairs, have already terminated union contracts covering just shy of half a million workers.

The executive orders, which mark the largest removal of union protections in US history, draw upon decades-old presidential powers to deny federal workers the right to collective bargaining on national security grounds.

In the past, this power has been used sparingly to restrict collective bargaining rights among certain employees working for US intelligence agencies such as the CIA or the National Security Agency.

The new orders extend this logic to employees at more than two dozen government agencies, including the departments of Veterans’ Affairs, Agriculture, Health and Human Services, the Patent Office and the Environmental Protection Agency. Law enforcement services such as the police were explicitly left out of the orders.

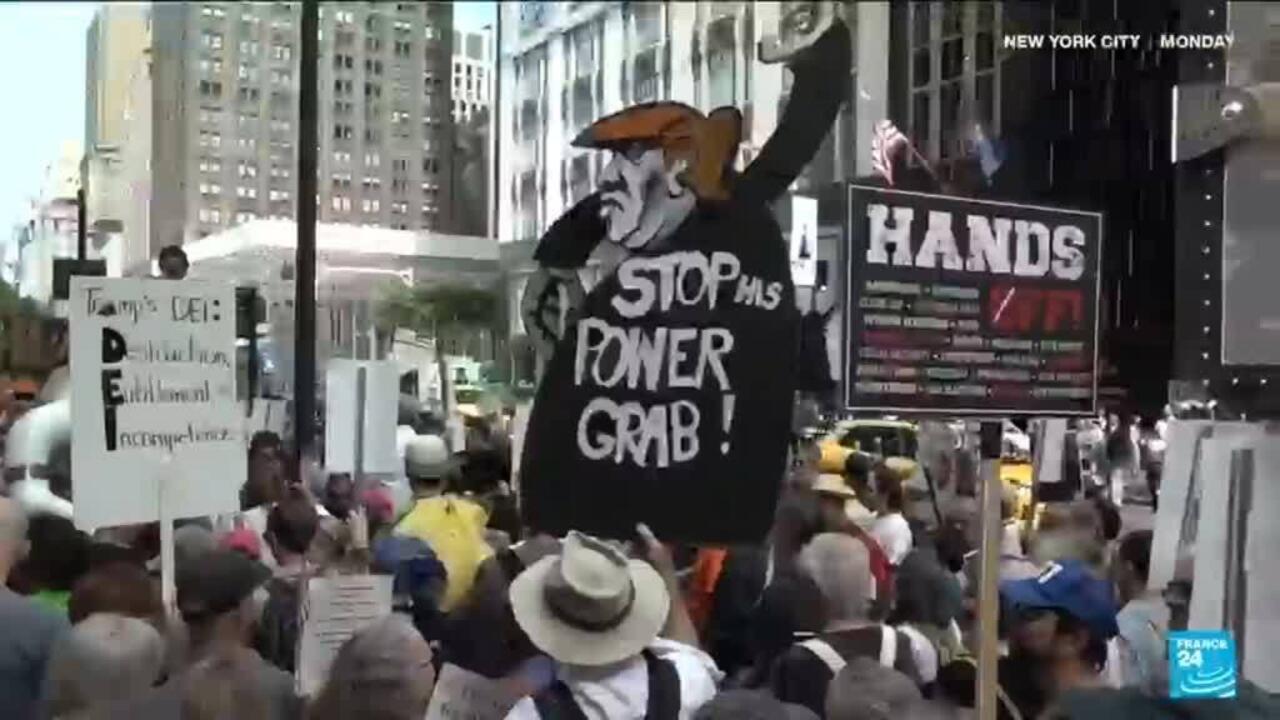

Labor Day protests against Trump and billionaires amid growing inequality

© France 24

02:08

02:08

Although framed as a national security push, “fact sheets” published by the White House make outright reference to union pushback against Trump’s efforts to radically downsize the federal workforce, accusing “certain Federal unions” of having “declared war” on the president’s agenda.

Unions representing workers at several of the agencies named in the executive orders have sued the Trump administration over what they maintain are violations of their members’ contracts, including the attempted mass firing of thousands of probationary workers.

Unions representing workers at several of the agencies named in the executive orders have sued the Trump administration over what they maintain are violations of their members’ contracts, including the attempted mass firing of thousands of probationary workers.

The backbone of the labour movement

Eunice Han, associate professor at the University of Utah’s Department of Economics, said that the federal workforce stood out as a stronghold of collective action in the US.

“Public sector unions really are the backbone of the labour movement in America,” she said. “While private-sector union membership has steadily declined since its peak during the 1960s, public sector unions have held relatively steady – today, only about 6 percent of private-sector workers are unionised, compared with over 30 percent in the public sector.”

Han said that Trump’s executive orders had to be understood in part as a response to a reawakening labour movement across the US.

“Historically, unions have leaned toward the Democratic Party, which has often resisted Trump’s agenda for various reasons,” she said. “At the same time, we’ve seen a national surge in unionisation during the 2020s – many industries experienced a new wave of organising, and public approval ratings for unions hit record highs. In that environment, Trump’s executive orders look less like a response to national security and more like part of a broader pushback against the resurgence of organised labour.”

According to a September 2024 Gallup poll, 70 percent of Americans approve of labour unions, marking the highest support since the 1950s. Petitions for union elections at the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) doubled between 2021 and 2024, with as many as 60 million workers reportedly saying they would vote to unionise if they could. Despite this, the percentage of workers represented by unions continues to stagnate.

White nationalist agenda? Minorities in front line of Trump policy targets

FRANCE 24

40:04

40:04

Lynn Rhinehart, a senior fellow at the Economic Policy Institute and former general counsel at the AFL-CIO, the country’s largest labour union federation, said that Trump’s executive orders marked the beginning of a longer campaign against organised labour.

“Trump's real motivation is clear – the executive order is a retaliatory action against federal employee unions who are standing in the way of Trump's union-busting agenda,” she said.

That agenda doesn’t stop with executive orders. Trump fired NLRB chair Gwynne Wilcox in January, saying that her opinions had “unduly disfavoured” employers. The decision – which Wilcox continues to fight in the courts – leaves the country’s top labour watchdog without the quorum it needs to hear cases and issue decisions.

Trump in July nominated two new board members, including Boeing’s chief labour counsel Scott Mayer, to restore a quorum. If confirmed by the Senate, the appointments will leave the five-member board with a Republican majority.

Spillover

While the scale of Trump’s efforts to strip federal workers of collective bargaining rights has no equal in US history, labour historians have drawn comparisons with then-president Ronald Reagan’s decision to fire and permanently replace some 11,500 striking air traffic controllers in 1981, breaking the back of a growing movement of public sector worker mobilisation.

“Both of these actions showed a president telling the world – and more particularly, telling employers – that it was open season on workers' collective bargaining rights,” Rhinehart said. “After Reagan fired the air traffic controllers, employers in the private sector were emboldened to replace strikers, hire union busters, and engage in other tactics to defeat union organising drives.”

The US labour movement has still not recovered from the blow. Fewer than one in 10 workers now belongs to a union – a number that’s fallen by half since 1983.

Han said that Trump’s assault on public-sector unions would likely also set off shockwaves across their counterparts in the private sector.

“Unlike private-sector unions … public-sector unions operate under different state-level rules – some states allow bargaining and strikes, while others ban them entirely,” she said.

“If the federal government starts weakening public sector bargaining rights, it sets a precedent that makes it easier for states to follow suit. And if public sector unions lose their standing, it will almost certainly spill over into the private sector, either through changes in federal labour law or through broader adoption of right-to-work legislation.”

Bridging the divide

But whether federal employees fighting to keep their hard-won union protections are able to draw support from the wider working public remains an open question. With private-sector union membership in freefall as employers fought tooth and nail to stop their workers organising, public servants found themselves more and more isolated within a labour movement now dominated by federal employees.

And as the Great Recession triggered by the 2008 financial crisis deepened the country’s yawning gulf between rich and poor, highly skilled professionals found themselves less hard-hit by the widespread job losses that fell heaviest on middle-skilled blue- and white-collar workers.

It is this reserve of potential resentment that conservative and libertarian groups have attempted to draw on to paint federal workers not as underpaid civil servants working for the common good, but an elite caste of privileged white-collar workers shielded from the ravages of the worsening economy by taxpayer dollars. At its heart, though, Han said the picture bore little likeness to the lives of most federal workers.

“That’s been a common talking point from anti-union groups, but the reality is more complicated,” she said. “Take teachers’ unions – the largest public-sector unions in the country. Our public-school teachers are underpaid, and teacher shortages are a serious issue in most major cities. In fact, about 40 percent of teachers can’t even bargain collectively despite being union members. During the wave of teacher strikes in 2018 and 2019, the public showed overwhelming support. I think that could happen again under the right conditions.”

Researchers maintain that more highly educated public sector workers tend to be underpaid compared to those working for private employers. Federal workers with a high-school education or less – such as groundskeepers, janitors and other custodial staff – are by contrast better paid than their private-sector counterparts.

But Han said that Trump’s re-election had exposed some of the cracks within the labour movement.

“I do think there’s a divide,” she said. “Traditionally, the private-sector industries with the highest union membership – manufacturing and construction – have been hit hard by globalisation and outsourcing. Trump’s promise to ‘bring jobs back’ resonated strongly with those workers.”

While much of the US’s labour union leadership backed Democratic candidate Kamala Harris during the 2024 presidential race, the base showed itself to be more divided on polling day. One CNN exit survey on the night of the election suggested that as many as 45 percent of union households may have cast their vote for Trump and his programme of economic protectionism.

“Public sector unions, on the other hand, tend to be more highly educated and remain strongly aligned with the Democratic Party,” Han said. “For Democrats to bridge that divide, they need to speak more directly to economic concerns – investing in infrastructure and R&D, helping workers transition into new technologies and addressing inequality at the top.”

Despite Trump’s efforts to brand himself as a pro-worker president, Rhinehart said, the Republican’s “existential” war on federal workers’ collective bargaining rights told a very different story.

“Trump's attacks on labour are detrimental to all workers, because unionisation raises wages and improves benefits for all workers, both union and non-union,” she said. “Unions are an important check on corporate power. Without unions, Trump and his corporate billionaire allies can run roughshod over workers and their rights.”