The hatefulness and histrionics of Trump’s allies exemplify how the ill-formed and culturally biased so easily make fools of themselves.

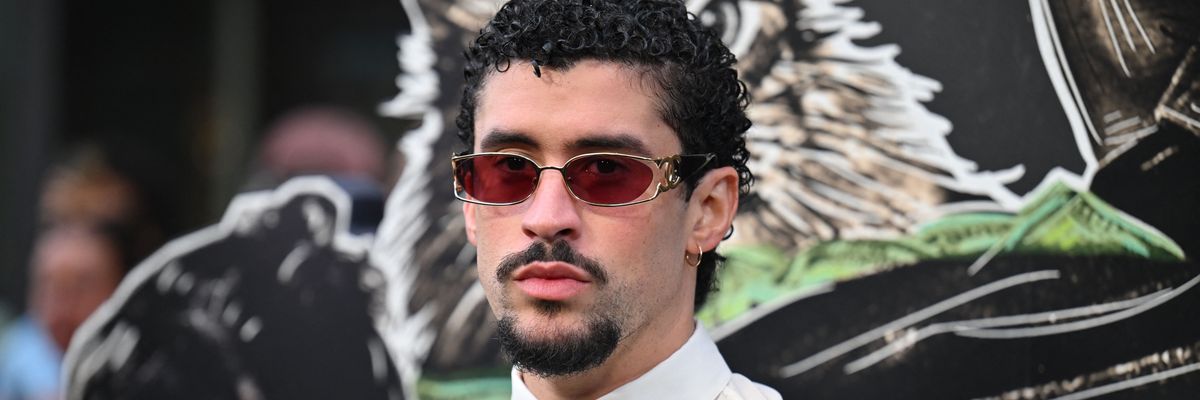

Puerto Rican singer Bad Bunny attends the premiere of "Caught Stealing" at the Regal Union Square in New York on August 26, 2025. (Photo by ANGELA WEISS/AFP via Getty Images)

Photo by ANGELA WEISS / AFP

Ernesto Sagás

Nov 08, 2025

Nov 08, 2025

Common Dreams

The selection of musical megastar Bad Bunny to headline the Super Bowl’s halftime show has ignited a storm of controversy among conservative circles. The ostensive reason is that Bad Bunny (born Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio) is a Puerto Rican who sings in Spanish, and thus according to his MAGA critics, he does not represent “America.”

For the new form of conservativism known as MAGA, the vision of America and Americans is narrow, and does not include the likes of Bad Bunny. Newsmax host Greg Kelly, for instance, claimed Bad Bunny “hates America, hates President Trump, hates ICE, [and] hates the English language!” Fox News host Tomi Lahren, meanwhile, claimed Bad Bunny is “Not an American artist.” Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson not only mislabeled Bad Bunny as “Bad Bunny Rabbit,” he argued Bad Bunny was not a role model, calling for replacing him with someone with “broader Appeal,” like 82-year-old Lee Greenwood.

The Bad Bunny controversy raises the question: what is America and how should it be represented?

The histrionics of MAGA leaders exemplify how the ill-formed and culturally biased so easily make fools of themselves. For instance, the trope that Bad Bunny is not American demonstrates profound ignorance. Bad Bunny was born in Bayamon, Puerto Rico. As such, he was a United States citizen at birth. Puerto Rico has been a US possession since its conquest in 1898, and its residents have been US citizens since the passage of the Jones Act in 1917.

As for Bad Bunny hating America, this claim is nothing short of odd. Though Bad Bunny did not support candidate Trump in 2024, and disagrees with ICE roundups, 75 million Americans did not vote for President Trump (something that residents of Puerto Rico cannot do), and we suspect millions of others, including the authors here, do not support mass ICE roundups. Such free speech stances, which are at the core of the First Amendment of the Constitution, in no way reflect any disdain for this country. As James Baldwin poignantly taught decades ago, and is the case for millions of others today, it is our love for this country that leads us to question it in order to push it towards our laudable goals of freedom and equality.

Further, Bad Bunny singing in Spanish in no way means he hates this country or its dominant language, English. Bad Bunny is fluent in English but prefers to sing in his native tongue of Spanish. While Trump proclaimed English as the country’s official language, such a declaration does not carry the weight of law. That edict also appears to run afoul of a host of US Supreme Court decisions embracing our multicultural and multilingual country, including Meyer v. Nebraska, which held invalid efforts to forbid teaching foreign languages, and Lau v. Nichols. holding that failure to provide non-English instruction violated students’ civil rights.

The United States of America is a multicultural, multiracial nation made up of the descendants of immigrants from all over the world, as well as Indigenous nations and other lands that were conquered during a period of US imperial expansion in the 19th century. Puerto Ricans have fought bravely and died valiantly in America’s wars since WWI, and they contribute in numerous ways to make America great. So, why being a Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican makes of Bad Bunny less of an American in MAGA cohorts?

For months now, we have been witnessing a whitewashing of the American experience spearheaded by the Trump administration. Museums, colleges and universities, and even our very diverse military have all been forced to scrub references to the valuable contributions made by women, people of color, and immigrants (except for white ones).

Puerto Ricans, a Spanish-speaking, Latin American people of color (who also happen to be US citizens), do not fit the MAGA mold, and Bad Bunny’s fame is a reminder that our nation, based on the principle of E pluribus unum (Out of many, one) can be proudly represented by many people in many ways.

Previous Super Bowl halftime performers, many of them foreign-born, have reflected our nation’s best (and diverse) talents, but suddenly, a Puerto Rican is not American enough? Turning Point USA’s “All American” alternative halftime show is quite revealing of MAGA’s cultural whitewashing attempts by promising “Anything in English.”

This piece was first published in the Miami Herald.

Our work is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). Feel free to republish and share widely.

Ediberto Roman

Ediberto Roman is professor of Law & Director of Immigration and Citizenship Initiatives at Florida International University.

Full Bio >

The selection of musical megastar Bad Bunny to headline the Super Bowl’s halftime show has ignited a storm of controversy among conservative circles. The ostensive reason is that Bad Bunny (born Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio) is a Puerto Rican who sings in Spanish, and thus according to his MAGA critics, he does not represent “America.”

For the new form of conservativism known as MAGA, the vision of America and Americans is narrow, and does not include the likes of Bad Bunny. Newsmax host Greg Kelly, for instance, claimed Bad Bunny “hates America, hates President Trump, hates ICE, [and] hates the English language!” Fox News host Tomi Lahren, meanwhile, claimed Bad Bunny is “Not an American artist.” Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson not only mislabeled Bad Bunny as “Bad Bunny Rabbit,” he argued Bad Bunny was not a role model, calling for replacing him with someone with “broader Appeal,” like 82-year-old Lee Greenwood.

The Bad Bunny controversy raises the question: what is America and how should it be represented?

The histrionics of MAGA leaders exemplify how the ill-formed and culturally biased so easily make fools of themselves. For instance, the trope that Bad Bunny is not American demonstrates profound ignorance. Bad Bunny was born in Bayamon, Puerto Rico. As such, he was a United States citizen at birth. Puerto Rico has been a US possession since its conquest in 1898, and its residents have been US citizens since the passage of the Jones Act in 1917.

As for Bad Bunny hating America, this claim is nothing short of odd. Though Bad Bunny did not support candidate Trump in 2024, and disagrees with ICE roundups, 75 million Americans did not vote for President Trump (something that residents of Puerto Rico cannot do), and we suspect millions of others, including the authors here, do not support mass ICE roundups. Such free speech stances, which are at the core of the First Amendment of the Constitution, in no way reflect any disdain for this country. As James Baldwin poignantly taught decades ago, and is the case for millions of others today, it is our love for this country that leads us to question it in order to push it towards our laudable goals of freedom and equality.

Further, Bad Bunny singing in Spanish in no way means he hates this country or its dominant language, English. Bad Bunny is fluent in English but prefers to sing in his native tongue of Spanish. While Trump proclaimed English as the country’s official language, such a declaration does not carry the weight of law. That edict also appears to run afoul of a host of US Supreme Court decisions embracing our multicultural and multilingual country, including Meyer v. Nebraska, which held invalid efforts to forbid teaching foreign languages, and Lau v. Nichols. holding that failure to provide non-English instruction violated students’ civil rights.

The United States of America is a multicultural, multiracial nation made up of the descendants of immigrants from all over the world, as well as Indigenous nations and other lands that were conquered during a period of US imperial expansion in the 19th century. Puerto Ricans have fought bravely and died valiantly in America’s wars since WWI, and they contribute in numerous ways to make America great. So, why being a Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican makes of Bad Bunny less of an American in MAGA cohorts?

For months now, we have been witnessing a whitewashing of the American experience spearheaded by the Trump administration. Museums, colleges and universities, and even our very diverse military have all been forced to scrub references to the valuable contributions made by women, people of color, and immigrants (except for white ones).

Puerto Ricans, a Spanish-speaking, Latin American people of color (who also happen to be US citizens), do not fit the MAGA mold, and Bad Bunny’s fame is a reminder that our nation, based on the principle of E pluribus unum (Out of many, one) can be proudly represented by many people in many ways.

Previous Super Bowl halftime performers, many of them foreign-born, have reflected our nation’s best (and diverse) talents, but suddenly, a Puerto Rican is not American enough? Turning Point USA’s “All American” alternative halftime show is quite revealing of MAGA’s cultural whitewashing attempts by promising “Anything in English.”

This piece was first published in the Miami Herald.

Our work is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). Feel free to republish and share widely.

Ediberto Roman

Ediberto Roman is professor of Law & Director of Immigration and Citizenship Initiatives at Florida International University.

Full Bio >

Ernesto Sagás

Ernesto Sagás is Professor of Ethnic Studies at Colorado State University. He has a Ph.D. in political science from the University of Florida with a concentration in Latin American studies.

Full Bio >

Bad Bunny and Puerto Rican Muslims: How both remix what it means to be Boricua

(The Conversation) — Like Bad Bunny’s music, Puerto Rican Muslims’ lives challenge ideas about race, religion and belonging in the Americas.

The Mezquita Al-Madinah in Hatillo, Puerto Rico, about an hour west of San Juan, is one of several mosques and Islamic centers on the island.

Ken Chitwood

November 6, 2025

(The Conversation) — Bad Bunny, born Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, is more than a global music phenomenon; he’s a bona fide symbol of Puerto Rico.

The church choir boy turned “King of Latin Trap” has songs, style and swagger that reflect the island’s mix of pride, pain and creative resilience. His music mixes reggaetón beats with the sounds of Puerto Rican history and everyday life, where devotion and defiance often live side by side.

Bad Bunny has been called one of Puerto Rico’s “loudest and proudest voices.” Songs like “El Apagón” – “The Blackout” – celebrate joy and protest together, honoring everyday acts of resistance to colonial rule and injustice in Puerto Rican life. Others, like “NUEVAYoL,” celebrate the sounds and vibrancy of its diaspora – especially in New York City. Some songs, like “RLNDT,” mention spiritual searching – featuring allusions to his own Catholic upbringing, sacred and secular divides, New Age astrology and Spiritism.

As a scholar of religion who recently wrote a book about Puerto Rican Muslims, I find echoes of that same strength and artistry in their stories. Although marginalized among Muslims, Puerto Ricans and other U.S. citizens, they find fresh ways to express their cultural heritage and practice their faith, creating new communities and connections along the way. Similar to Bad Bunny’s music, Puerto Rican Muslims’ lives challenge how we think about race, religion and belonging in the Americas.

Bad Bunny performs during his ‘No Me Quiero Ir De Aqui’ residency on July 11, 2025, in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Kevin Mazur/Getty Images

Stories of struggle

There are no exact numbers, but before recent crises, Puerto Rico – an archipelago of 3.2. million people – had about 3,500 to 5,000 Muslims, many of them Palestinian. Economic hardship, natural disasters such as hurricanes Irma and Maria, and government neglect have since forced many to leave, however.

As of 2017, there were also an estimated 11,000 to 15,400 Puerto Rican Muslims among the nearly 6 million Puerto Ricans and nearly 4 million Muslims in the United States.

Like any Puerto Rican, these Muslims know the struggles of colonialism’s ongoing impact, from blackouts and economic inequality to racism. For example, in the viral 23-minute video for “El Apagón,” journalist Bianca Graulau outlines how tax incentives for external investors are displacing locals – a theme reinforced in Bad Bunny’s later song, “Lo Que Le Pasó a Hawaii.”

The video for “El Apagón” includes a short documentary about gentrification on the archipelago.

Converts to Islam also face unique challenges – and not just Islamophobia. Many are told they are “not real Puerto Ricans” because of their newfound faith. Some are treated as foreigners in their own families and friend groups, often asked whether they are abandoning their culture to “become Arab.”

To be a Puerto Rican Muslim, then, is to negotiate being and belonging at numerous intersections of diversity and difference.

Still, some connect their Muslim identity to moments in Puerto Rican history. In interviews, they told me how they identify with Muslims who came with Spanish conquistadors during colonial times. Others draw inspiration from enslaved Africans brought to the Caribbean. Many of them were Muslim and resisted their condition in ways large and small: fleeing to the forest to pray, for example, or living as “maroons” – people who escaped and formed their own communities.

Many ways to be Puerto Rican

Puerto Rican culture cannot be neatly mapped onto a single tradition. The archipelago’s religion, music and art blend together influences from Indigenous Taíno, African, Spanish and American cultures. Religious processions pass by cars blasting reggaetón. Shrines to Our Lady of Divine Providence stand beside U.S. chain restaurants and murals demanding independence.

Bad Bunny embodies this fusion. He is rebellious yet rooted, irreverent yet deeply Puerto Rican. His music blends contemporary sounds from reggaetón and Latin trap with traditional “bomba y plena.” It all adds up to something distinctly “Boricua,” a term for Puerto Ricans drawn from the Indigenous Taíno name for the island, “Borikén.”

A mural in San Juan, Puerto Rico, photographed in 2017, says, ‘We don’t understand this democracy.’

Mark Ralston/AFP via Getty Images

Puerto Rican Muslims wrestle with what it means to be authentically Boricua, though. In particular, their lives reveal how religion is both a boundary and a bridge: defining belonging while creating new ways to imagine it.

Since Spanish colonization in the 1500s, most Puerto Ricans have been Roman Catholic. But over the past two centuries, many other Christian groups have arrived, including Seventh-day Adventists, Lutherans and Pentecostals. Today, more than half of Puerto Ricans identify as Catholic and about one-third as Protestant.

Alongside these traditions, Afro-Caribbean traditions such as Santería, Espiritismo and Santerismo – a mix of the two – remain active. There are also small communities of Jews, Rastafari and Muslims.

Even with this diversity, converts to Islam are sometimes accused of betraying their culture. One young man told me that when he became Muslim, his mother said he had not only betrayed Christ but also “our culture.”

Yet Puerto Rican Muslims point to Arabic influences in Spanish words. They celebrate traces of Islamic design in colonial and revival architecture that reflects Muslims’ multicentury presence in Spain, from the 700s until the fall of the last Muslim kingdom in Granada in 1492. They also cook up halal versions of classic Puerto Rican dishes.

Like Bad Bunny, these converts remix what it means to be Puerto Rican, showing how Puerto Rico’s sense of identity – or “puertorriqueñidad” – is not exclusively Christian, but complex and constantly evolving.

A member of the Council in Defense of the Indigenous Rights of Boriken, dressed in Taino traditional clothing, sounds a conch during a march through San Juan, Puerto Rico, on July 11, 2020.

Ricardo Arduengo/AFP via Getty Images

In solidarity

Many Puerto Rican converts frame their faith as a counternarrative, rejecting the Christianity imposed by Spanish colonizers. They also resist Islamophobia, racism and foreign domination, with some converts drawn to the religion as a way to oppose these forces. Similar to Bad Bunny’s music, which often critiques colonialism and social constraints, they push back against systems that try to define who they can be.

To that end, Puerto Rican Muslims also build connections with other groups facing injustice. In reggaetón terms, they form their own “corillos” – groups of friends – united by shared struggles.

They demonstrate on behalf of Palestinians, seeing them as another colonized people without a nation. The first Latino Muslim organization, Alianza Islámica – founded by Puerto Rican converts in 1987 – emerged out of the era’s push for minorities’ rights around the New York City metro area. And after the 2016 Pulse Nightclub shooting, where about half of the 49 victims killed were Puerto Rican, and the mosque attended by the shooter was intentionally set on fire, Boricua Muslims joined with LGBTQ+, Muslim and Latino communities to grieve and demand justice.

Pro-Palestine supporters attend a rally to end the war on Nov. 12, 2023, in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Miguel J. Rodríguez Carrillo/VIEWpress via Getty Images

In these ways, Puerto Rican Muslims remind me that notions of community, identity or justice do not stand on their own. For many people, they are linked – parts of the same fight for dignity and freedom.

That is why, when I listen to songs like “NUEVAYoL” or “El Apagón,” I think of the Puerto Rican Muslims I know in places such as Puerto Rico, Florida, New Jersey, Texas and New York. Their stories, like Bad Bunny’s music, show how being Puerto Rican today means constantly negotiating who you are and where you belong. And that religion, like music, can carry the sound of struggle – but also the hope of one day overcoming the injustices and inequalities of everyday life.

(Ken Chitwood, Affiliate Researcher, Religion and Civic Culture Center, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences; Bayreuth University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

The Conversation religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The Conversation is solely responsible for this content.

(The Conversation) — Like Bad Bunny’s music, Puerto Rican Muslims’ lives challenge ideas about race, religion and belonging in the Americas.

The Mezquita Al-Madinah in Hatillo, Puerto Rico, about an hour west of San Juan, is one of several mosques and Islamic centers on the island.

Ken Chitwood

November 6, 2025

(The Conversation) — Bad Bunny, born Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, is more than a global music phenomenon; he’s a bona fide symbol of Puerto Rico.

The church choir boy turned “King of Latin Trap” has songs, style and swagger that reflect the island’s mix of pride, pain and creative resilience. His music mixes reggaetón beats with the sounds of Puerto Rican history and everyday life, where devotion and defiance often live side by side.

Bad Bunny has been called one of Puerto Rico’s “loudest and proudest voices.” Songs like “El Apagón” – “The Blackout” – celebrate joy and protest together, honoring everyday acts of resistance to colonial rule and injustice in Puerto Rican life. Others, like “NUEVAYoL,” celebrate the sounds and vibrancy of its diaspora – especially in New York City. Some songs, like “RLNDT,” mention spiritual searching – featuring allusions to his own Catholic upbringing, sacred and secular divides, New Age astrology and Spiritism.

As a scholar of religion who recently wrote a book about Puerto Rican Muslims, I find echoes of that same strength and artistry in their stories. Although marginalized among Muslims, Puerto Ricans and other U.S. citizens, they find fresh ways to express their cultural heritage and practice their faith, creating new communities and connections along the way. Similar to Bad Bunny’s music, Puerto Rican Muslims’ lives challenge how we think about race, religion and belonging in the Americas.

Bad Bunny performs during his ‘No Me Quiero Ir De Aqui’ residency on July 11, 2025, in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Kevin Mazur/Getty Images

Stories of struggle

There are no exact numbers, but before recent crises, Puerto Rico – an archipelago of 3.2. million people – had about 3,500 to 5,000 Muslims, many of them Palestinian. Economic hardship, natural disasters such as hurricanes Irma and Maria, and government neglect have since forced many to leave, however.

As of 2017, there were also an estimated 11,000 to 15,400 Puerto Rican Muslims among the nearly 6 million Puerto Ricans and nearly 4 million Muslims in the United States.

Like any Puerto Rican, these Muslims know the struggles of colonialism’s ongoing impact, from blackouts and economic inequality to racism. For example, in the viral 23-minute video for “El Apagón,” journalist Bianca Graulau outlines how tax incentives for external investors are displacing locals – a theme reinforced in Bad Bunny’s later song, “Lo Que Le Pasó a Hawaii.”

The video for “El Apagón” includes a short documentary about gentrification on the archipelago.

Converts to Islam also face unique challenges – and not just Islamophobia. Many are told they are “not real Puerto Ricans” because of their newfound faith. Some are treated as foreigners in their own families and friend groups, often asked whether they are abandoning their culture to “become Arab.”

To be a Puerto Rican Muslim, then, is to negotiate being and belonging at numerous intersections of diversity and difference.

Still, some connect their Muslim identity to moments in Puerto Rican history. In interviews, they told me how they identify with Muslims who came with Spanish conquistadors during colonial times. Others draw inspiration from enslaved Africans brought to the Caribbean. Many of them were Muslim and resisted their condition in ways large and small: fleeing to the forest to pray, for example, or living as “maroons” – people who escaped and formed their own communities.

Many ways to be Puerto Rican

Puerto Rican culture cannot be neatly mapped onto a single tradition. The archipelago’s religion, music and art blend together influences from Indigenous Taíno, African, Spanish and American cultures. Religious processions pass by cars blasting reggaetón. Shrines to Our Lady of Divine Providence stand beside U.S. chain restaurants and murals demanding independence.

Bad Bunny embodies this fusion. He is rebellious yet rooted, irreverent yet deeply Puerto Rican. His music blends contemporary sounds from reggaetón and Latin trap with traditional “bomba y plena.” It all adds up to something distinctly “Boricua,” a term for Puerto Ricans drawn from the Indigenous Taíno name for the island, “Borikén.”

A mural in San Juan, Puerto Rico, photographed in 2017, says, ‘We don’t understand this democracy.’

Mark Ralston/AFP via Getty Images

Puerto Rican Muslims wrestle with what it means to be authentically Boricua, though. In particular, their lives reveal how religion is both a boundary and a bridge: defining belonging while creating new ways to imagine it.

Since Spanish colonization in the 1500s, most Puerto Ricans have been Roman Catholic. But over the past two centuries, many other Christian groups have arrived, including Seventh-day Adventists, Lutherans and Pentecostals. Today, more than half of Puerto Ricans identify as Catholic and about one-third as Protestant.

Alongside these traditions, Afro-Caribbean traditions such as Santería, Espiritismo and Santerismo – a mix of the two – remain active. There are also small communities of Jews, Rastafari and Muslims.

Even with this diversity, converts to Islam are sometimes accused of betraying their culture. One young man told me that when he became Muslim, his mother said he had not only betrayed Christ but also “our culture.”

Yet Puerto Rican Muslims point to Arabic influences in Spanish words. They celebrate traces of Islamic design in colonial and revival architecture that reflects Muslims’ multicentury presence in Spain, from the 700s until the fall of the last Muslim kingdom in Granada in 1492. They also cook up halal versions of classic Puerto Rican dishes.

Like Bad Bunny, these converts remix what it means to be Puerto Rican, showing how Puerto Rico’s sense of identity – or “puertorriqueñidad” – is not exclusively Christian, but complex and constantly evolving.

A member of the Council in Defense of the Indigenous Rights of Boriken, dressed in Taino traditional clothing, sounds a conch during a march through San Juan, Puerto Rico, on July 11, 2020.

Ricardo Arduengo/AFP via Getty Images

In solidarity

Many Puerto Rican converts frame their faith as a counternarrative, rejecting the Christianity imposed by Spanish colonizers. They also resist Islamophobia, racism and foreign domination, with some converts drawn to the religion as a way to oppose these forces. Similar to Bad Bunny’s music, which often critiques colonialism and social constraints, they push back against systems that try to define who they can be.

To that end, Puerto Rican Muslims also build connections with other groups facing injustice. In reggaetón terms, they form their own “corillos” – groups of friends – united by shared struggles.

They demonstrate on behalf of Palestinians, seeing them as another colonized people without a nation. The first Latino Muslim organization, Alianza Islámica – founded by Puerto Rican converts in 1987 – emerged out of the era’s push for minorities’ rights around the New York City metro area. And after the 2016 Pulse Nightclub shooting, where about half of the 49 victims killed were Puerto Rican, and the mosque attended by the shooter was intentionally set on fire, Boricua Muslims joined with LGBTQ+, Muslim and Latino communities to grieve and demand justice.

Pro-Palestine supporters attend a rally to end the war on Nov. 12, 2023, in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Miguel J. Rodríguez Carrillo/VIEWpress via Getty Images

In these ways, Puerto Rican Muslims remind me that notions of community, identity or justice do not stand on their own. For many people, they are linked – parts of the same fight for dignity and freedom.

That is why, when I listen to songs like “NUEVAYoL” or “El Apagón,” I think of the Puerto Rican Muslims I know in places such as Puerto Rico, Florida, New Jersey, Texas and New York. Their stories, like Bad Bunny’s music, show how being Puerto Rican today means constantly negotiating who you are and where you belong. And that religion, like music, can carry the sound of struggle – but also the hope of one day overcoming the injustices and inequalities of everyday life.

(Ken Chitwood, Affiliate Researcher, Religion and Civic Culture Center, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences; Bayreuth University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

The Conversation religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The Conversation is solely responsible for this content.

No comments:

Post a Comment