Rethinking Marcuse, Rethinking Marxism

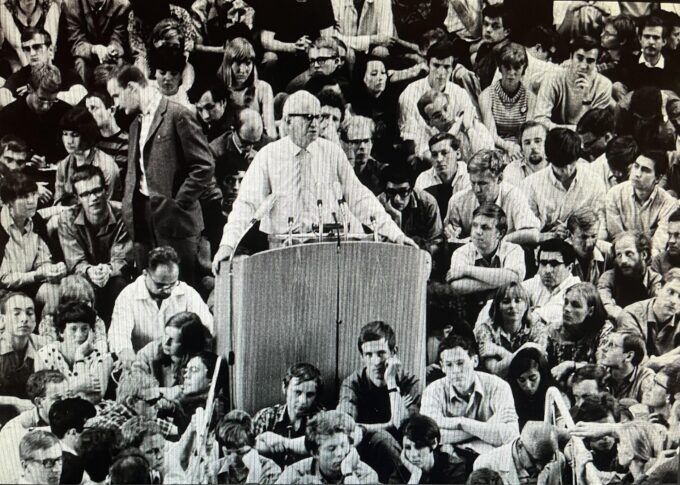

Marcuse giving a lecture in Berlin, 1967. Photograph Source: Isaactrius – CC BY-SA 4.0

CounterPunch recently republished two compelling articles about Herbert Marcuse.

Charles Reitz’s study, “When Marxist Intellectuals Collaborated With the CIA,” (December 12, 2025); and Michael Yates interview with Gabriel Rockhill, “An Insider Critique of the Imperial Theory Industry” (December 15, 2025).

The Yates interview with Rockhill originally appeared in Monthly Review and reads like a rejoinder to Reitz’s piece. The Rockhill interview is a provocative, if at times incoherent, discussion of what Rockhill calls the differences between “Western Marxism” and “Marxism Leninism.” In the interview, Rockhill argues:

A significant portion of my most recent book is dedicated to an analysis of the superstructures of the leading imperialist countries and the various ways in which they have fostered Western Marxist discourses as a weapon of ideological warfare against the version of Marxism defended by Lenin.

The book he is referring to is his, Who Paid the Pipers of Western Marxism? (Monthly Review Press, 2025). And the interview may not do full justice to Rockhill’s analysis.

Rockhill spends a goodly portion of the interview arguing that “Western Marxism” has been fully integrated into capitalist society, notably in reformist politics and academia. Other than a handful of passing references to Lenin, he never actually discusses Lenin’s works nor the “Marxism Leninist” movement that followed. In this way, he artfully avoids discussing how the Bolshevik party, the “party of the proletariat,” became the party oppressing the proletariat. Nor how Leninism – let alone “Western Marxism” — gave way to Stalinism and the Chinese Communist state.

Rockhill never defines “Marxism Leninism.” However, Reitz acknowledges, “Rockhill views Che’s legacy as consistent with other leading lights, such as Lenin, Mao, Ho Chi Minh, and Fidel Castro (338), who were at the helm of real socio-economic alternatives to capitalism in practice.” Thus, “Marxism Leninism” seems to be the spirit of the Lenin of 1917 and the revolutionary spirit of many others before taking power.

Sadly, this is not 1917 and an all-too-simplistic invocation of yesteryear doesn’t address today’s ever-mounting social and political crises. And too this, one can only recall that what the Situationists once identified as “the spectacle” reverberates through all forms of social life in postmodern capitalism, including academia and ideologies.

The most intriguing aspect of the Rockhill interview is his discussion of Herbert Marcuse. As he said, “I have to admit that I was a bit surprised myself when I first started to piece together the study that became, over the years, the last chapter of the book.” He then notes:

By reading some excellent scholarship in German, working through Marcuse’s long FBI file, consulting State Department and CIA records, and doing research at the Rockefeller Archive Center, it became crystal clear to me that Marcuse was being disingenuous in the interviews where he was asked about his work for the U.S. state.

Rockhill goes further, adding, “He actually did regularly collaborate with the CIA …” He then draws on the work of Tim Müller, director of research and administrative director of the Hamburg Institute for Social Research. Rockhill notes that Marcuse “was involved in the drafting of at least two National Security Estimates (the highest level of intelligence of the U.S. government).” He adds, “He was also the leading intellectual in the Rockefeller Foundation’s Marxism-Leninism Project, where he worked hand in glove with his close friend, Philip Mosely, who was a high-level, long-term CIA advisor.”

He then insists, “This extremely well-funded, transatlantic project had the explicit mission of internationally promoting Western Marxism over and against Marxism-Leninism.”

Sadly, Rockhill fails to note that Marcuse, a German-Jewish Marxist intellectual fleeing Nazi Germany, came to the United States in 1934. Stephen Gennaro and Douglas Kellner, in “Under Surveillance: Herbert Marcuse and the FBI,” point out that Marcuse worked – along with Theodore Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Franz Neumann and Leo Lowenthal — at the Institute branch at Columbia from 1934 to 1939.”

Between 1942 and 1944, he — along with Neumann and Otto Kirchheimer, among others Jewish intellectual émigrés who fled Germany for the U.S — were headhunted from posts in American universities by General William “Wild Bill” Donovan, the leader of the OSS, and reunited in the service of the U.S. government.

Going further, they point out, “Marcuse had worked as a researcher, translator, and informant at the Office of War Information (OWI), Bureau of Intelligence, beginning in December 1942 and then with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) from April 1943 until September 1945, before becoming the Chief of the Central European Branch of the Division of European Research for the State Department.” They also note that the feds “conducted routine FBI investigations of Marcuse between 1942 and 1952.”

Marcuse, in a discussion with Jürgen Habermas, reflected on this period:

Marcuse: At first I was in the political division of the OSS and then in the Division of Research and Intelligence of the State Department. My main task was to identify groups in Germany with which one could work toward reconstruction after the war, and to identify groups which were to be taken to task as Nazis. There was a major de-Nazification program at the time. Based on exact research, reports, newspaper reading, and whatever, lists were made up of those Nazis who were supposed to assume responsibility for their activity. . .

Habermas: Are you of the impression that what you did was of any consequence?

Marcuse: On the contrary. Those whom we had listed first as “economic war criminals” were very quickly back in the decisive positions of responsibility in the German economy. It would be very easy to name names here.

Reitz notes, Marcuse faced “a second wave of inquiries, with regard to his loyalty to the U.S. during his 1950s employment by the State Department, discloses that the FBI consulted with HUAC concerning his case.” Going further, he found, “During the 1960s he was also under surveillance in connection with his ties to the New Left and international student movements.”

Perhaps most disappointing in the Rockhill interview is any discussion of Marcuse’s more critical, anti-capitalist works. Reitz details some of them, including the 1947 essay, “33 Theses toward the Military Defeat of Hitler-Fascism.” Quoting Reitz:

It theorizes neofascism as the emergent political expression of totalitarian governance in the advanced industrial countries of the anti-Soviet post-war West. [T]he world is dividing into a neofascist and a Soviet camp. … [T]here is only one alternative for revolutionary theory: to ruthlessly and openly criticize both systems and to uphold without compromise orthodox Marxist theory against both.

Reitz argued, “In ‘33 Theses,’ in contrast to Rockhill’s main criterion of Marxist revisionism, does not draw social theory into a camp compatible with US imperialism, quite the contrary. Marcuse did not hesitate to the US as itself tending towards a neofascist future.”

Going further, Reitz insisted, “I do find Rockhill’s ‘deep dive’ (61) into Marcuse’s work to be astonishingly faulty in depicting his work as that of an archetypal pied piper paid to use Marxism in a defanged manner that also somehow defends the imperial world project of the US. Nothing in Marcuse is a defense of Western society in Marxist or any other terms.”

Read both articles. Radical Marxism is needed now more than ever.

No comments:

Post a Comment