Why the West is an Unreliable Partner for the Global South

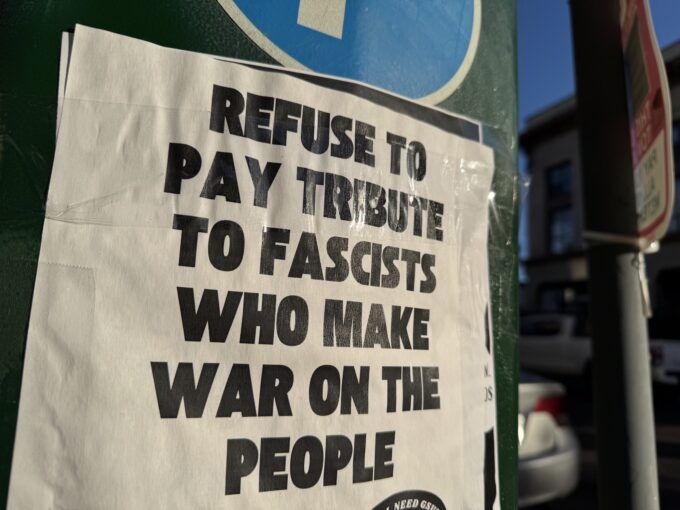

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

“I’m a revolutionary,” says Vijay Prashad midway through the conversation, “but not the kind who, from a soapbox, decrees what must happen. That’s revolutionary arrogance. What you do need to do is carefully analyze what the world really looks like and how it’s evolving. Only then can you try to exert as much influence as possible within that reality.”

Vijay Prashad is a leading voice in the global debate on decolonization and just international relations. He has written forty books, runs the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research, publishes on the news platform Globetrotter, and is the publisher of LeftWord Books. Tricontinental is headquartered in Chile with offices in India, Brazil, South Africa, and Argentina. LeftWord publishes from New Delhi, while Vijay himself lives in Santiago.

In early December, Vijay Prashad was in Belgium, where he spoke at five universities. The talk at the VUB was titled “From Bandung to Gaza.” In April 1955, a historic meeting of liberation movements and newly independent countries from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia took place in the Indonesian city of Bandung. Bandung marked a historical turning point, writes David Van Reybrouck in Revolusi, his monumental work on the Indonesian struggle for independence: “Here, no borders were drawn or territorial agreements made, but new dynamics were unleashed, across national borders.” These dynamics gave Egypt the courage to challenge Britain and nationalize the Suez Canal. Bandung convinced German and French leaders that European states must unite, “if Europe were not to be crushed in the near future by the peoples of Asia and Africa.”

Bandung also fueled Pan-African thinking and the independence ambitions of people like Patrice Lumumba, and in the United States inspired both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. in their struggle for equal civil rights. Vijay Prashad puts it this way: “Bandung is more than that 1955 conference. Saying ‘Bandung’ is essentially saying: ‘The South has its own ideas.’ Even seventy years later, the West still sees itself as the source of ideas and the South as a hotbed of rebels. Yet leaders from Asia, Africa, and Latin America were also thinkers. Who today reads Che Guevara’s 1965 speech in Algiers about the global economy? Who knows Ho Chi Minh’s work on the importance of following a good (patriotic) example and on moral responsibility toward others?”.

In fact, says Prashad, Simón Bolívar articulated the essence two hundred years earlier: we need a new global balance. “That was the driving force behind generations of anti-colonial struggles. It was what animated Lumumba and the Congolese independence movement: the demand to establish a new balance in the international order, one in which peoples from the Global South could also govern their own nations. Moreover, conferences like the one in Bandung created a space where these leaders and thinkers could engage in dialogue.” Bandung took place against the dual backdrop of the collapse of European colonial rule and the new global order brought about by the Cold War. The so-called Non-Aligned Countries, mostly from the Global South, refused to align themselves with the US and the then-Soviet Union. They did not want to be mere playthings of major powers but rather to position themselves as a third force on the international stage.

Did the Non-Aligned Project survive after the Cold War?

Vijay Prashad: “The struggle for their own ideas and solutions is still just as relevant seventy years after Bandung. Look at Gaza. The Palestinians are really not interested in Western ideas for the future. Whether we believe in a two-state solution or not is less relevant than what they themselves want. What we can do is help create the conditions for them to realize their own solutions. That means fighting for the release of political prisoners like Marwan Barghouti, who has been imprisoned for 23 and a half years, or Ahmad Saadat. They can take the lead in political negotiations.”

The “spirit of Bandung” suffered a blow with the collapse of the Soviet Union, but the real defeat of the Third World had already occurred almost a decade earlier, with the debt crisis that erupted in Mexico in 1982. The enormous threat of loans and debt was not entirely unexpected. In 1965, Kwame Nkrumah, one of the pioneers of the Pan-African cause and then president of Ghana, wrote Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. His basic thesis was that Europeans first exploited and plundered Africa’s wealth, then granted independence to impoverished nations, and then offered development loans, creating a new dependency.

What that truly meant became clear after 1982, when the International Monetary Fund brought one country after another from the Global South to its knees. Worse still, the Global South’s self-confidence vanished. Leaders once again looked to Washington for solutions instead of to their own strengths and to each other.

Perhaps the debt crisis and the structural adjustment programs imposed at the time were even worse for the development prospects of the Global South than the colonial legacy they had shaken off during the Bandung period?

Vijay Prashad: “Indeed. But the defeat of the South wasn’t definitive. Namibia is a good example. When that country in southern Africa was a German colony, the Germans committed their first genocide against the Herero and the Nama, thirty years before the Holocaust. After a long struggle for independence against the South African apartheid regime, Namibia became independent, but in the 1990s, the SWAPO liberation movement also had to submit to the dictates of the IMF. Pride was left behind, the national project shattered.”

In 2022, that self-awareness returned. At the Munich Security Conference, the Namibian Prime Minister was confronted by a German attendee because Namibia did not condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila replied that it was “not her war” and recalled that her liberation struggle had received support from the Soviet Union at the time, while Europe supported South Africa.

Where did she find the confidence to so decisively put Germany, Europe, and the West in their place? Namibia wasn’t suddenly debt-free, but it was freed from its one-sided dependence on institutions controlled by the West.

Today, African countries can also turn to institutions like the New Development Bank and other Chinese-funded institutions in the Global South. If the US Federal Reserve makes a fuss, they simply go to Beijing and talk to the People’s Bank of China. This proves that the spirit of Bandung isn’t dead, but was merely stored away, waiting for better times.

The New Development Bank isn’t just a Chinese project, but was established within the BRICS framework. Is this partnership of several emerging economies the Global South’s response to what it sees as neocolonial dominance by the West?

Vijay Prashad: “It’s not about a single platform, but about a deeper shift. The turning point for the Global South was the 2008 financial crisis. It became painfully clear then that their growing exports couldn’t rely solely on the sputtering and stagnant European markets. This explains the almost desperate U-turn within BRICS in 2009, when all sorts of initiatives were launched to facilitate, stimulate, and accelerate South-South trade. Since then, we’ve seen, among other things, the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (better known as the New Silk Roads), the revival of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the RCEP free trade area with fifteen countries in the Asia-Pacific region, and so on.”

It is striking that Russia is often considered part of the Global South today, despite its long history of colonial expansion in Central Asia and occupation in Eastern Europe, and the fact that it continues to pursue a form of imperialist policy even after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Vijay Prashad: “That certainly has to do with the historical experience with the Soviet Union. The Indian freedom fighter and later prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru traveled to Russia in 1927 and wrote an influential book about it, in which he advocated a similar revolution in India. Even historians are mistaken when they think that Woodrow Wilson’s 14-point speech in 1918 was the starting signal for national liberation movements, while Lenin’s writings on the self-determination of peoples were far more influential. Lenin viewed the Tsarist regime as an imperial power, which was why large parts of the Russian Empire were granted the status of autonomous republics after the 1917 revolution.”

Moreover, many countries in the South view Russia as an Asian rather than a European nation, even though Russians consider themselves European. Russia has indeed attempted to join the existing imperialist world order, including through its participation in the G8. Since its expulsion, it has increasingly presented itself as part of the developing world: as an emerging nation rather than as a member of the dominant world.

Not only was Russia expelled from the G8, but since its aggressive war against Ukraine, Western sanctions have also been pouring in.

Vijay Prashad: “The West made a huge mistake by increasingly resorting to economic sanctions. The 2012 decision to ban Iranian banks from the Swift system of international payments, in particular, came as a stark warning throughout the Global South. Suddenly, the realization dawned that the Global South had to build its own systems, otherwise it would forever remain dependent on European political approval. The West is unreliable: in conflict situations, it appears willing to freeze the assets of other states or cut countries off from the global market.”

The West has politicized the economy and global trade. This is a mistake, and even the Chinese Communist Party realizes it. Global trade and development should not depend on Western political preferences.

Speaking of the Global South suggests a cohesive bloc, a shared vision, and common interests. But when we look at Gaza, it’s striking that Arab countries, for example, enthusiastically cooperate with Trump’s “peace proposals” but do little to stop Israel.

Vijay Prashad: “The attitude of countries like Jordan and Egypt is simply shameful. The Jordanian queen, who is of Palestinian descent, gave good interviews, but the king did nothing. He didn’t threaten to terminate the 1948 agreement between Israel and Jordan if the bombings continued. The Egyptian army, with all its F-16s, refused to act.”

In the Arab world, you see how pan-Arab nationalism has been overshadowed by the conservative influence of the Saudi royal family. You see the same thing in Palestine. The pan-Arabists are behind Israeli bars, and the Muslim Brotherhood is present on the ground. This is no coincidence, and it plays into the hands of Israel and Western powers in the Middle East.

Tensions also exist within the BRICS, for example, between China and India. Can the alliance develop into a genuine alternative that also benefits the least developed countries?

Vijay Prashad: “The question of inequality within the Global South is crucial. In 1990, the South Commission—a group of 28 prominent individuals from the Global South chaired by Julius Nyerere—released the report “The Challenge to the South.” This was partly a response to the 1980 Brandt Report, in which the Commission on International Development identified the North-South divide as the central problem.

The South Commission argued that the issue was not just about wealth disparities, but also about an uneven distribution of power. To address this dual problem, the report advocated that the strongest economies in the South should function as locomotives, to which other countries could connect their economies and thus gain momentum.

Metaphors are seductive, but also misleading. Neoliberal globalization was sold with the image of rising waters that would lift boats both large and small. In reality, that rising water turned out to be a storm: small fishing boats capsized, while war and merchant fleets grew even more powerful. Why should we believe that the locomotives from the Global South will actually pull the poorest countries along with them?

Vijay Prashad: “The Chinese president’s first foreign visit of the year always takes place in an African country. This has been a tradition since the 1960s. The fact that it receives little coverage in the Western news does not diminish its importance. Moreover, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation was established in 2000, bringing together China, the African Union, and 53 African countries. This forum also traditionally meets at the beginning of the year.”

In recent years, China has made it clear at that Forum that the way trade is conducted is causing excessive trade surpluses and thus increasing instability, including in China. This benefits no one. That’s why China wants to co-invest in strengthening the processing industry in Africa, so that African countries no longer have to simply export raw materials, but can also realize some of the added value domestically.

Yet it will take a long time before that train really gets moving. National development plans are needed for that, and that presupposes that states must be rebuilt, with all the relevant capacity required. Everything that disappeared under the IMF’s wrecking ball must be rebuilt: the financial infrastructure, ministries, national banks, and even a kind of African Central Bank. That takes time. In the meantime, China is willing to transfer knowledge and technology, much like Japan did for China in the early days of the reforms. These are real processes, in the material world. We have to work with them.

The Palestinian pan-Arabists are behind Israeli bars, and the Muslim Brotherhood is present on the ground. This is no coincidence, and it plays into the hands of Israel and Western powers in the Middle East.

Also real and increasingly material is Make America Great Again. Do you see Trump and his MAGA movement as a restoration of the United States as the dominant superpower, or rather as the chaotic and tragic end of the long American century?

Vijay Prashad: “It’s certainly not the latter. Every ‘end’ is a new beginning, and so American power won’t disappear anytime soon—it will rather take on new forms. Even after the defeat of Nazi Germany, we saw former Nazis in Germany, but also in countries like Chile, gain new positions and opportunities.”

MAGA itself is a consequence of policies that preceded it. We have to go back to the 1980s, when the government and social security were dismantled, while tax havens flourished. Social democrats then used austerity policies to shoot themselves in the head. Entire societies were brutalized, and what we’re seeing now is the reaction to that.

MAGA relies on the brutalized masses who reject the elite. It’s not a project for the future, but political violence in response to societal violence. You can only undo that by rebuilding a society that functions not only for the elite, but also for working people. It’s therefore tragic that social democrats aren’t working on this.

Why do you use the population-elite dichotomy, when that’s precisely the language of the far right and MAGA? From a Marxist, I’d expect you to at least speak of rich and poor, or workers and capitalists?

Vijay Prashad: “It’s true that our vocabulary must stem from reality, from the struggles people face. In that sense, it’s indeed better to speak of rich and poor. Yet, I also find ‘elite’ useful because it contains ‘elitist.’ Many people who are rich or powerful do indeed live in a different universe and look down on the rest of humanity.”

Just as the West looks down on the peoples of the Global South, Western support for Israel has meanwhile undermined the credibility of the values and world order that Europe has always championed. Are we losing universal human rights precisely at a time when they are needed more than ever?

Vijay Prashad: “I don’t think Western support for Israel undermines universal human rights themselves. This isn’t new, by the way. After Guantanamo, the illegal invasion of Iraq, Abu Ghraib, and American torture chambers in Poland and elsewhere, the United Nations was mobilized and the Responsibility to Protect agreement (also known as R2P, the responsibility to protect the population against its own rulers, ed.) was established. Human rights and internationalism didn’t disappear; they were actually strengthened.”

Even when the US and NATO exploited R2P for regime change in Libya, international cooperation and multilateralism were revived. The real problem is that the collective West still dominates and controls the global information system. When the major Anglo-Saxon media outlets write that human rights are outdated, the whole world repeats it. Still.

Koenraad Boogaert of Ghent University argues that the credibility of universal human rights is fundamental, because social movements use that language to conduct and justify their struggles.

Vijay Prashad: “Of course, you must embrace and defend the universality of human rights with both hands. It starts with the treaty obligations that all UN member states have to recognize and safeguard human rights. It’s sometimes a bit complicated, because some countries in the Global South rightly stand up for their sovereignty, but not necessarily for the universal and equal rights and dignity of all their citizens. Iran is an example of this. Russia too.”

Anyone who abandons the language of human rights also abandons the pursuit of socialism. Because the right to development is also part of human rights discourse—and attempts are still being made to translate that right into binding treaty law. The US continually blocks this, but the fight is not over. We must continue to stand up for good and universal health care, decent housing for all, and decent work. These are human rights.

In the debate on anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism, much attention is paid to political and economic sovereignty, but surprisingly little to the ecological concerns of the Global South or the climate responsibility of the North.

Vijay Prashad: “It’s not that it’s not being discussed or written about at all. For example, the Brazilian Tricontinental team published an excellent analysis of the climate crisis as a crisis of capitalism before the COP in Belém, with a particular focus on the energy issue and its connections to development. If you ignore these connections, it becomes a desperate debate about species extinction, destroyed biodiversity, and out-of-control warming.”

Incidentally, while everyone was watching the Climate Summit in Brazil, another international meeting was taking place in Nairobi that received little attention, but which may have greater implications for the climate and climate justice. At that meeting of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on the UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation, proposals were discussed to combat tax evasion and avoidance and to give countries in the Global South more control over the profits generated within their territories.

The proposal to impose an additional tax on CO2 polluters was rejected by the EU and the US. Meanwhile, the EU did have a voice in Belem. This contradiction between these two simultaneous yet conflicting positions is an ecological debate that could make a real difference.

Yet, the necessary development and increased prosperity in the Global South in 2026 can no longer be viewed separately from the ecological impact and the limits of our planet.

Vijay Prashad: “I completely agree. But we also can’t lose sight of the primary responsibility of the Global North. A Brown University study showed that the US military is the world’s largest institutional CO2 polluter. And now the European NATO member states have pledged to spend 5 percent of their GDP on defense.”

According to Scientists for Global Responsibility, a $100 billion increase in military spending results in an average of 32 million tons of additional CO2 emissions. If you take the raw numbers, you get an idea of what the promised increase in defense budgets by 2035 means in terms of CO2 emissions.

Last year, NATO member states collectively spent approximately $1.15 trillion on defense. If all member states achieve the promised 5 percent, that figure will rise to $2.54 trillion. Calculated linearly, that means an additional 365 million tons of CO2 — almost as much as the entire annual emissions of countries like Italy or the United Kingdom. The problem, in other words, isn’t your individual footprint, but your defense emissions!

No comments:

Post a Comment