Human Ancestors Invented Stone Tools Several Times

The excavation site, known as Bokol Dora 1 or BD 1, is close to the 2013 discovery of the oldest fossil attributed to our genus Homo discovered at Ledi-Geraru in the Afar region of northeastern Ethiopia. The fossil, a jaw bone, dates to about 2.78 million years ago, some 200,000 years before the then oldest flaked stone tools. The Ledi-Geraru team has been working for the last five years to find out if there is a connection between the origins of our genus and the origins of systematic stone tool manufacture. |

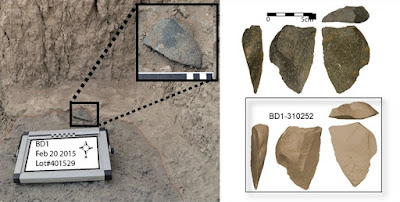

| A large green artefact found in situ at the Bokol Dora site. Right: Image of the same artefact and a three dimensional model of the same artefact [Credit: David R. Braun] |

Sediment layer with animal bones and stone chips

It took several years to excavate through meters of sediments by hand before exposing an archaeological layer of animal bones and hundreds of small pieces of chipped stone representing the earliest evidence of our direct ancestors making and using stone knives. The site records a wealth of information about how and when humans began to use stone tools.

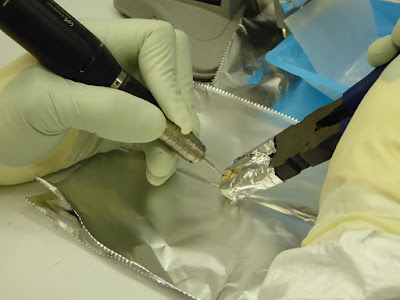

|

| Blade Engda of the University of Poitiers lifts an artefact from 2.6 million year old sediment exposing an imprint of the artefact on the ancient surface below [Credit: David R. Braun] |

Habitat change

Kaye Reed, who studies the site’s ecology, is director of the Ledi-Geraru Research Project and a research associate with Arizona State University’s Institute of Human Origins along with Campisano, notes that the animals found with these tools were similar to those found only a few kilometers away with the earliest Homo fossils.

"The early humans that made these stone tools lived in a totally different habitat than 'Lucy' did," says Reed. Lucy is the nickname for an older species of hominin known as Australopithecus afarensis, which was discovered at the site of Hadar, Ethiopia, about 45 kilometers southwest of the new BD 1 site. "The habitat changed from one of shrubland with occasional trees and riverine forests to open grasslands with few trees. Even the fossil giraffes were eating grass!"

In addition to dating a volcanic ash several meters below the site, project geologists analyzed the magnetic signature of the site’s sediments. Over the Earth’s history, its magnetic polarity has reversed at intervals that can be identified. Other earlier archaeological sites near the age of BD 1 are in "reversed" polarity sediments. The BD 1 site is in "normal" polarity sediments. Because the reversal from "normal" to "reversed" happened at about 2.58 million years ago, the geologists knew that BD 1 was older than all the previously known sites.

The recent discovery of older hammering or "percussive" stone tools in Kenya dated to 3.3 million years ago, described as "Lomekwian", and butchered bones in Ethiopia shows the deep history of our ancestors making and using tools. However, recent discoveries of tools made by chimpanzees and monkeys have challenged "technological ape" ideas of human origins.

Archaeologists working at the BD 1 site wondered how their new stone tool discovery fit into this increasingly complex picture of hominin behavioural evolution. What they found was that not only were these new tools the oldest artifacts yet ascribed to the "Oldowan", a technology originally named after finds from Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, but also were distinct from tools made by chimpanzees, monkeys or even earlier human ancestors.

Little in common with other tools

"We expected to see some indication of an evolution from the Lomekwian to these earliest Oldowan tools. Yet when we looked closely at the statistical patterns in the stone artefacts, there was very little connection to what has been described from older archaeological sites or to the stone tools modern primates are making," said Will Archer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig and the University of Cape Town, South Africa.

|

| An image of the Bokol Dora excavation during the 2015 excavation. Stones were placed on the contact surface during the excavation to preserve the fragile stratigraphic contacts [Credit: David Feary] |

Something changed by 2.6 million years ago, and our ancestors became more accurate and skilled at striking the edge of stones to make tools. The BD 1 artifacts captures this shift. It appears that this shift in tool making occurred around the same time that our ancestor’s teeth began to change. This can be seen in the Homo jaw from Ledi-Geraru. As our ancestors began to process food prior to eating using stone tools, we start to see a reduction in the size of their teeth. Our technology and biology were intimately intertwined even as early as 2.6 million years ago.

New ways of manufacturing tools

The lack of clear connections with earlier stone tool technology suggests that tool use was invented multiple times in the past. David Braun, an archaeologist with George Washington University and the lead author on the paper, noted, "Given that primate species throughout the world routinely use stone hammers to forage for new resources, it seems very possible that throughout Africa many different human ancestors found new ways of using stone artifacts to extract resources from their environment. If our hypothesis is correct then we would expect to find some type of continuity in artifact form after 2.6 million years ago, but not prior to this time period. We need to find more sites."

Aerial photography around the Bokol Dora site [Credit: David Feary]

The findings are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Source: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft [June 03, 2019]