Males are the other half of the story, so tiny and drab they’re often missed in oversized webs

Out in the open, female jorō spiders look eye-smacking obvious, but they’re sneaky hitchhikers. They can hide in wheel wells and under car hoods, tricks that might facilitate their spread.

By Susan Milius

Some thumbnail-sized, brown male spiders in Georgia could be miffed if they paid the least attention to humans and our news obsessions.

Recent stories have made much of “giant” jorō spiders invading North America from eastern Asia, some large enough to span your palm. Lemon yellow bands cross their backs. Bright red bits can add drama, and a softer cheesecake yellow highlights the many joints on long black legs.

The showy giants, however, are just the females of Trichonephila clavata. Males hardly get mentioned except for what they’re not: colorful or big. A he-spider hulk at 8 millimeters barely reaches half the length of small females. Even the species nickname ignores the guys. The word jorō, borrowed from Japanese, translates to such unmasculine terms as “courtesan,” “lady-in-waiting” and even “entangling or binding bride.”

Mismatched sexes are nothing new for spiders. The group shows the most extreme size differences between the sexes known among land animals, says evolutionary biologist Matjaž Kuntner of the Evolutionary Zoology Lab in Ljubljana, Slovenia. The most dramatic case Kuntner has heard of comes from Arachnura logio scorpion spiders in East Asia, with females 14.8 times the size of the males.

With such extreme size differences, mating conflicts in animals can get violent: females cannibalizing males and so on (SN: 11/13/99). As far as Kuntner knows, however, jorō spiders don’t engage in these “sexually conflicted” extremes. Males being merely half size or thereabouts might explain the relatively peaceful encounters.

When it comes to humans, these spiders don’t bother anybody who doesn’t bother them. But what a spectacle they make. “I’ve got dozens and dozens in my yard,” says ecologist Andy Davis at the University of Georgia in Athens. “One big web can be 3 or 4 feet in diameter.” Jorō spiders have lived in northeastern Georgia since at least 2014.

These new neighbors inspired Davis and undergraduate Benjamin Frick to see if the newcomers withstand chills better than an earlier invader, Trichonephila clavipes, their more tropical relative also known as the golden silk orb-weaver. (The jorō also can spin yellow-tinged silk.) The earlier arrival’s flashy females and drab males haven’t left the comfy Southeast they invaded at least 160 years ago.

Figuring out the jorō’s hardiness involves taking the spider’s pulse. But how do you do that with an arthropod with a hard exoskeleton? A spider’s heart isn’t a mammallike lump circulating blood through a closed system. The jorō sluices its bloodlike fluid through a long tube open at both ends. “Think of a garden hose,” says Davis. He has measured heart rates of monarch caterpillars, and he found a spot on a spider’s back where a keen-eyed observer can count throbs.

Female jorō spiders packed in ice to simulate chill stress kept their heart rates some 77 percent higher than the stay-put T. clavipes, tests showed. Checking jorō oxygen use showed females have about twice the metabolic rate. And about two minutes of freezing temperatures showed better female survival (74 percent versus 50 percent). Lab tests used only the conveniently big jorō females, though male ability to function in random cold snaps could matter too.

Plus jorō sightings in the Southeast so far suggest the newer arrival needs less time than its relative to make the next generation, an advantage for farther to the north. The adults don’t need to survive deep winter in any case. Mom and dad die off, in November in Georgia, and leave their hundreds of eggs packed in silk to weather the cold and storms.

Reports on the citizen-observer iNaturalist site suggest that in Georgia, jorō spiders already cover some 40,000 square kilometers, Davis and Frick report February 17 in Physiological Entomology. Sightings now stretch into Tennessee and the Carolinas. But how far the big moms and tiny dads will go and when, we’ll just have to wait and see.

CITATIONS

A.K. Davis and B.L. Frick. Physiological evaluation of newly invasive jorō spiders (Trichonephila clavata) in the southeastern USA compared to their naturalized cousin, Trichonephila clavipes. Physiological Entomology. Published online February 17, 2022. doi: 10.1111/phen.12385.I

E.R. Hoebeke et al. Nephila clavata L. Koch, the jorō spider of East Asia, newly recorded from North America (Araneae: Nephilidae). PeerJ. Published online February 5, 2015. doi: 10.7717/peerj.763

M. Kuntner and J.A. Coddington. Sexual size dimorphism: Evolution and perils of extreme phenotypes in spiders. Annual Review of Entomolog. Vol. 65, January 2020, p. 57. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011019-025032.

About Susan Milius

Susan Milius is the life sciences writer, covering organismal biology and evolution, and has a special passion for plants, fungi and invertebrates. She studied biology and English literature.

Everyone knows that humans and most other vertebrate species hear using eardrums that turn soundwave pressure into signals for our brains. But what about smaller animals like insects and arthropods? Can they detect sounds? And if so, how?

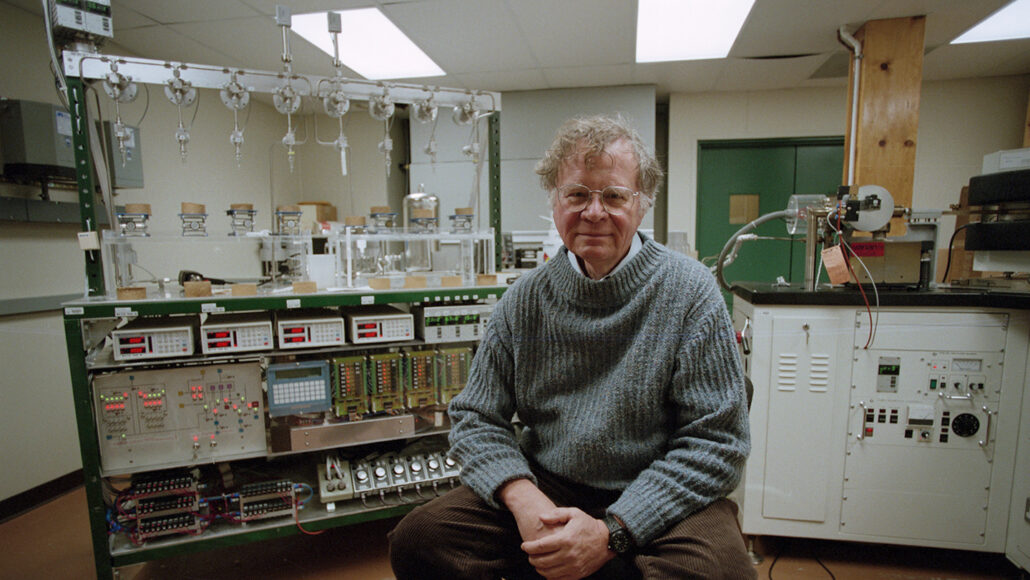

Distinguished Professor Ron Miles, a Department of Mechanical Engineering faculty member at Binghamton University's Thomas J. Watson College of Engineering and Applied Science, has been exploring that question for more than three decades, in a quest to revolutionize microphone technology.

A newly published study of orb-weaving spiders -- the species featured in the classic children's book "Charlotte's Web" -- has yielded some extraordinary results: The spiders are using their webs as extended auditory arrays to capture sounds, possibly giving spiders advanced warning of incoming prey or predators.

The paper, "Outsourced Hearing in an Orb-Weaving Spider that Uses its Web as an Auditory Sensor," published March 29 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides the first evidence that a spider can outsource hearing to its web.

It is well-known that spiders respond when something vibrates their webs, such as potential prey. In these new experiments, researchers for the first time show that spiders turned, crouched or flattened out in response to sounds in the air.

The study is the latest collaboration between Miles and Ron Hoy, a biology professor from Cornell, and it has implications for designing extremely sensitive bio-inspired microphones for use in hearing aids and cell phones.

Jian Zhou, who earned his PhD in Miles' lab and is doing postdoctoral research at the Argonne National Laboratory, and Junpeng Lai, a current PhD student in Miles' lab, are co-first authors. Miles, Hoy and Associate Professor Carol I. Miles from the Harpur College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Biological Sciences at Binghamton are also authors for this study. Grants from the National Institutes of Health to Ron Miles funded the research.

A single strand of spider silk is so thin and sensitive that it can detect the movement of vibrating air particles that make up a soundwave, which is different from how eardrums work. Ron Miles' previous research has led to the invention of novel microphone designs that are based on hearing in insects.

"The spider is really a natural demonstration that this is a viable way to sense sound using viscous forces in the air on thin fibers," he said. "If it works in nature, maybe we should have a closer look at it."

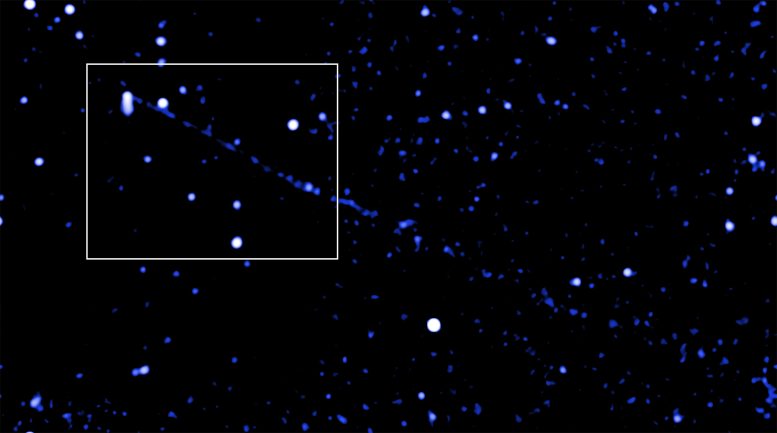

Spiders can detect miniscule movements and vibrations through sensory organs on their tarsal claws at the tips of their legs, which they use to grasp their webs. Orb-weaver spiders are known to make large webs, creating a kind of acoustic antennae with a sound-sensitive surface area that is up to 10,000 times greater than the spider itself.

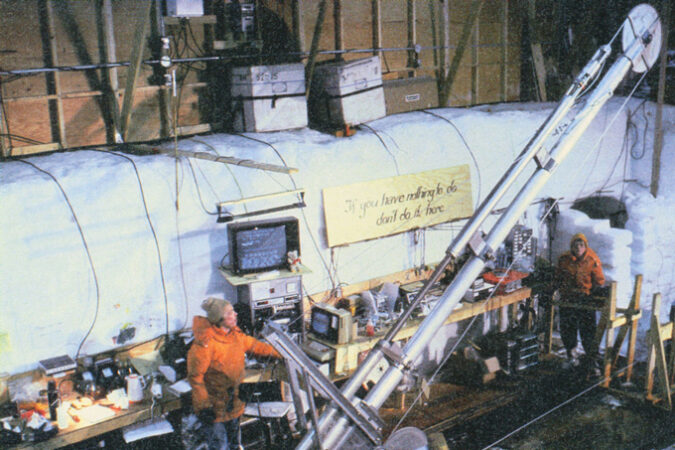

In the study, the researchers used Binghamton University's anechoic chamber, a completely soundproof room under the Innovative Technologies Complex. Collecting orb-weavers from windows around campus, they had the spiders spin a web inside a rectangular frame so they could position it where they wanted.

The team began by using pure tone sound 3 meters away at different sound levels to see if the spiders responded or not. Surprisingly, they found spiders can respond to sound levels as low as 68 decibels. For louder sound, they found even more types of behaviors.

They then placed the sound source at a 45-degree angle, to see if the spiders behaved differently. They found that not only are the spiders localizing the sound source, but they can tell the sound incoming direction with 100% accuracy.

To better understand the spider-hearing mechanism, the researchers used laser vibrometry and measured over one thousand locations on a natural spider web, with the spider sitting in the center under the sound field. The result showed that the web moves with sound almost at maximum physical efficiency across an ultra-wide frequency range.

"Of course, the real question is, if the web is moving like that, does the spider hear using it?" Miles said. "That's a hard question to answer."

Lai added: "There could even be a hidden ear within the spider body that we don't know about."

So the team placed a mini-speaker 5 centimeters away from the center of the web where the spider sits, and 2 millimeters away from the web plane -- close but not touching the web. This allows the sound to travel to the spider both through air and through the web. The researchers found that the soundwave from the mini-speaker died out significantly as it traveled through the air, but it propagated readily through the web with little attenuation. The sound level was still at around 68 decibels when it reached the spider. The behavior data showed that four out of 12 spiders responded to this web-borne signal.

Those reactions proved that the spiders could hear through the webs, and Lai was thrilled when that happened: "I've been working on this research for five years. That's a long time, and it's great to see all these efforts will become something that everybody can read."

The researchers also found that, by crouching and stretching, spiders may be changing the tension of the silk strands, thereby tuning them to pick up different frequencies. By using this external structure to hear, the spider could be able to customize it to hear different sorts of sounds.

Future experiments may investigate how spiders make use of the sound they can detect using their web. Additionally, the team would like to test whether other types of web-weaving spiders also use their silk to outsource their hearing.

"It's reasonable to guess that a similar spider on a similar web would respond in a similar way," Ron Miles said. "But we can't draw any conclusions about that, since we tested a certain kind of spider that happens to be pretty common."

Lai admitted he had no idea he would be working with spiders when he came to Binghamton as a mechanical engineering PhD student.

"I've been afraid of spiders all my life, because of their alien looks and hairy legs!" he said with a laugh. "But the more I worked with spiders, the more amazing I found them. I'm really starting to appreciate them."

Video: https://youtu.be/PIrotdSIxG4

Journal Reference:

Jian Zhou, Junpeng Lai, Gil Menda, Jay A. Stafstrom, Carol I. Miles, Ronald R. Hoy, Ronald N. Miles. Outsourced hearing in an orb-weaving spider that uses its web as an auditory sensor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2022; 119 (14) DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2122789119