Australia says US price floor backdown won’t derail its critical minerals strategy

Australia on Friday said it would support its critical mineral supply chains after the US stepped back from plans to guarantee a minimum price for such projects.

Shares of Australia’s rare earth miners fell sharply on Thursday after Reuters reported on the Trump administration’s retreat.

The sector was still in the red on Friday. Lynas, the world’s biggest producer of rare earths outside China, was down by more than 4%.

The backdown was communicated to US mining executives by Trump administration officials and indicated a lack of congressional funding for price floors and the complexity of setting market pricing, Reuters reported.

That “won’t stop Australia (from) pursuing our critical minerals strategic reserve program to make sure Australia has access to the resources it needs to build a future made in Australia,” Resources Minister Madeleine King told Sky News on Friday.

“We know from what we’ve seen in reports and we will let that play out … the US has introduced a price floor for one particular project and that’s the only one it has done it for, and that was a game-changer.”

Australia has been positioning itself as a critical minerals alternative to China, the world’s biggest producer, for use in the automotive and defence sectors.

It has said it would establish a A$1.2 billion ($840 million) strategic reserve of minerals that it believes is vulnerable to supply disruption.

The stockpile, which will prioritize antimony, gallium and rare earth elements, is expected to be ready by the second half of 2026.

The government is also considering setting a price floor to support local critical minerals projects as part of its strategy.

“We’ll have a number of mechanisms, a floor price will be one through offtake agreements,” King said. “We are determined to make sure there is value for taxpayer money in the reserve and in any floor price.”

($1 = 1.4278 Australian dollars)

(By Christine Chen; Editing by Thomas Derpinghaus)

Mozambique’s president opens Chinese-owned graphite processing plant

Mozambique’s President Daniel Chapo opened a 200,000 metric ton per year graphite processing plant at a Chinese-owned mine on Friday, as the south-east African country boosts output of the battery mineral.

Annual global mined graphite production is 1.6 million metric tons, the United State Geological Survey estimates and Mozambique is one of the world’s top producers of the mineral, which is an excellent conductor of heat and electricity and is used in batteries for electric vehicles and mobile phones.

China has the world’s largest graphite reserves and dominates its mining and processing as well.

Chapo said Mozambique, where French oil major TotalEnergies is resuming construction of a $20 billion liquefied natural gas project, was working to make the most of its natural resources.

“Today we are entering the world’s industrial map,” he said, adding: “We are no longer a supplier of raw materials, but a producer, processor and exporter of materials”.

Chinese company DH Mining, which started work on the graphite mine in Nipepe in 2014, said it had invested $200 million on mining and processing facilities.

DH Mining director Sang Shong said the venture, in Mozambique’s northern province of Niassa, currently employs 890 workers and this is set to rise to 2,000 in its second phase.

Australia’s Syrah Resources and Dutch metals firm AMG have graphite mining operations in neighbouring Cabo Delgado province. Another Australian group, Triton Minerals, is also advancing its Ancuabe project in Cabo Delgado.

(By Custodio Cossa and Nelson Banya; Editing by Alexander Smith)

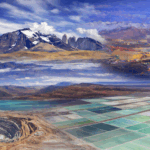

From copper to selenium: Chile maps critical minerals

Chile has published its National Critical Minerals Strategy, a plan to position the country as a reliable supplier amid surging global demand driven by artificial intelligence, new technologies and the energy transition.

Unveiled in the final weeks of President Gabriel Boric’s term, the strategy signals a shift beyond the country’s traditional reliance on copper toward a broader mix of resources aligned with a decarbonizing global economy.

The framework identifies 14 critical minerals: copper, lithium, molybdenum, rhenium, cobalt, rare earth elements, antimony, selenium, tellurium, gold, silver, iron ore, boron and iodine.

Chile has grouped these minerals based on its current position in global markets. Copper, lithium, molybdenum and rhenium form the first group, where Chile already holds strong shares of global supply at 23%, 20.4%, 14.6% and 46.8%, respectively, and where other major economies also classify the minerals as critical.

A second group covers minerals with no current production or only potential participation, including cobalt, rare earth elements, antimony, selenium and tellurium.

A third group includes minerals already extracted domestically that offer opportunities to deepen Chile’s role in global value chains, such as gold, silver, iron ore, boron and iodine.

Industry verdict

Juan Ignacio Guzmán, head of Santiago-based mineral consulting firm GEM, said the way the strategy defines critical minerals reflects a balance between economic priorities and broader social expectations.

“Overall, the strategy reflects a good balance between Chile’s economic interests and legitimate environmental and social concerns, precisely in how it defines which minerals should be considered critical,” he said, adding that the challenges will vary sharply by category.

According to Guzmán, category A minerals, where Chile is already a major producer, are largely associated with brownfield developments.

“These are mines that are already established, and where there is a well-structured social and environmental framework that has developed over time,” he said. “That part is more straightforward.” The more complex test, he said, will come from category B minerals, where Chile has little or no production today. “In those cases, it basically requires breaking new ground socially and environmentally, and that is where the role of the State is most critical.”

Other analysts were more sceptical about the strategy’s practical impact. José Cabello, director of Mineralium Consulting Group, said the document does little to signal a near-term increase in production.

“There is nothing new in the wording of the strategy that would imply a definitive boost to Chile’s production of critical minerals,” he told MINING.COM.

Cabello said that while the strategy outlines ambitions, it stops short of committing to concrete action. “Although it is not explicitly stated in the text, the strategy lacks a decision to bring new critical mineral projects into production at an early stage in Chile, such as cobalt, tungsten or rare earths,” he said. “Practical short-term production proposals are notably absent.”

He attributed that gap to institutional weaknesses rather than geology. “This major shortcoming in a mining country is due to the fact that the current authorities of the state mining agencies lack direct experience in the mining industry,” Cabello said, adding that this “reflects an inability to resolve basic, concrete problems.”

He said the issue is visible in the document itself, “where commonplaces prevail and there are even several unnecessary repetitions.”

Daniel Weinstein, partner and head of the mining practice at Morales & Besa and president of the advisory council at the Ministry of Mining, told MINING.COM the strategy could still influence Chile’s mining outlook if it is followed by concrete action.

“It can, mainly because it gives Chile a clearer way to prioritize what ‘critical’ means for the country and it sets up an implementation framework that can be tracked,” he said.

“This is still a strategy, not a law, so it won’t change investment conditions by itself.” The impact, he added, will depend on whether the forthcoming action plan delivers clearer ownership, timelines and funding, and leads to faster, more predictable project execution.

Weinstein also noted that copper and lithium are likely to remain the main focus for investment over the next five years, given Chile’s scale and pipeline.

“Where the strategy adds an interesting angle is the attach-rate opportunity,” he said, pointing to minerals that can be developed through existing operations and processing streams, including molybdenum and rhenium, as well as selective by-product recovery such as selenium, tellurium and, in some cases, antimony.

“Cobalt and rare earths could also gain momentum, but that will be more project-specific and partner-dependent.”

On regulation, Weinstein said the strategy provides direction but not certainty. “Investors will still focus on permitting performance in practice,” he said. “The remaining uncertainty is execution: institutional capacity, consistency across agencies and regions, and whether timelines actually improve on real projects.”

Mirco Hilgers, partner in energy, mining and infrastructure and head of the environmental practice at Baker & McKenzie, in Santiago, said the strategy marks a new phase in Chile’s mining history by expanding its ambition beyond copper. He said it elevates resources such as lithium, cobalt and rare earth elements into the country’s official policy framework, positioning Chile as a key player in the global energy transition.

The document defines critical minerals as those essential to priorities including the energy transition, food security, defence and resilient supply chains. For mining countries like Chile, it also ties the designation to economic growth, local value creation, diversification and research and development.

Reliable partner

The strategy seeks to reinforce Chile’s image as a diversified and responsible supplier by promoting value-added industries and strengthening international partnerships. Hilgers said the approach rests on both political and legal foundations, pointing to laws on citizen participation and public administration that embed transparency and inclusion. He added that the 30-day public consultation is central to the strategy’s credibility and designed to build public trust into resource policy.

Mining Minister Aurora Williams, Economy and Energy Minister Álvaro García, Corfo Vice President José Miguel Benavente and industry representatives attended the presentation of the plan. Boric said it sets out coordinated and gradual public action to boost competitiveness, develop value chains and build resilience across the mining sector.

Guzmán said the most difficult challenge will not be technical but political and social. “The main difficulty will be generating the conditions for companies to regain trust in the system and for real changes to occur,” he said. “This will require managing the political capital that exists to effectively convince society of the need to implement this strategy.” He added that, even with broad stakeholder agreement, the next step is public persuasion. “It is extremely important to convince society of the role Chile must play in the world’s critical minerals, as well as of the challenges and requirements we will face.”

Hilgers described the strategy as a geopolitical signal at a time when the United States, Europe and Asia have elevated critical mineral supply security to matters of national strategy. By articulating its own vision, he said, Chile places itself at the centre of the debate and could unlock access to financing, technology transfer and new industrial ecosystems. He cautioned that success will depend on execution, with water stress, community expectations and permitting delays remaining structural challenges.

Years in the making

The strategy emerged from a multi-year participatory process combining technical analysis and stakeholder engagement, including studies by the state copper commission, Cochilco, and mining regulator, Sernageomin. It also includes work funded by the Inter-American Development Bank between 2024 and 2025. A high-level advisory committee of 16 representatives, a technical committee of 120 specialists from 56 institutions, regional workshops and public consultation all fed into the final document.

Despite the hurdles, Hilgers said the potential upside is significant. Copper will remain the backbone of the sector, he said, but developing a wider set of critical minerals could redraw Chile’s industrial map and mark the start of a broader industrial reinvention.

Latin America is heading into 2026 with resources at the centre of a growing global power struggle, as governments and investors focus on who controls critical minerals and the supply chains behind them. If the region matters to you, don’t miss MINING.COM’s new series tracking the geopolitical forces reshaping it and why markets are increasingly

No comments:

Post a Comment