Framing the climate crisis as a terrorism issue could galvanize action

In many vulnerable regions of the world, the climate crisis has exacerbated loss of farmable land and increased water scarcity, fueling rural-urban migration, civil unrest, and violence. As a result, worsening geopolitical instability has aided the rise of terrorism and violence in the Middle East, Guatemala, and the Lake Chad Basin of Africa. Yet when people hear the words, "global warming," they typically don't think of terrorism. If they did, politicians would be far more likely to undertake drastic action to address the climate crisis.

Syria after 2011 is one example of how the climate crisis multiplied existing threats. Water scarcity, which had been worsening over the years, contributed significantly to the outbreak of conflict. The increased death of livestock, reduced arable land, and rise in food insecurity made it significantly easier for the terror organization calling itself the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) to locally recruit over two thirds of its fighters. Extreme weather phenomena offered ripe opportunities for ISIS to increase support among locals. When a vicious drought swept through Iraq in 2010, ISIS distributed food baskets to local inhabitants. When high winds destroyed vegetation in 2012, ISIS handed out cash to affected farmers. By offering a source of income and opportunity for people when their livelihoods were destroyed by droughts and other extreme weather, ISIS was able to cultivate support and draw members from local populations. In other words, the climate crisis increased geopolitical instability and aided the growth of terrorism.

The US is vehemently opposed to terrorism as a matter of national security. According to the Pew Research Center, in early 2018, over three-quarters of American adults believed terrorism should be a top policy priority for the government, the highest of any given option. Over 46 percent of American adults favored increasing spending on anti-terrorism defenses, though the US military budget is already larger than the next seven highest-spending countries combined. The same survey showed that less than half of American adults believed climate change should be a top policy priority, ranking the second lowest of given issues.

Most Americans see "global warming" as an environmental, scientific, and political issue. Over half of Americans do not see it as a national security issue. While it is informative to present the climate crisis primarily through scientific data on global temperatures, atmospheric carbon concentration, and emissions levels, it does not galvanize people to action nearly as much as characterizing it as a matter of immediate national security. Doing the latter would make it a much higher priority for people in power.

The U.S. military already quietly recognizes climate change as a matter of national security, in part because it sparks conflict and unrest in other countries. In order to conceptually link the climate crisis to national security for the broader public, climate activists should expand and increase rhetorical focus on how the climate crisis worsens migration, foments geopolitical instability, and thereby aids terrorist organizations. Presenting the climate crisis in security-centric concerns and consequences ensures that all Americans—including right-leaning voters and people who would not be swayed by conventional appeals to ecological conservation or species preservation—become aware of how consequential it is. Security-centric framing would also help to shift the tone of climate activism toward addressing immediate threats, rather than simply encouraging global cooperation for the sake of future generations.

Reorienting climate rhetoric around national security also brings the action to a level that feels more achievable—at the national rather than global level. Whereas preserving the planet for future generations sounds aspirational and spiritually uplifting, it is an intrinsically international goal that calls upon many countries to work together for success. Framing plans to deal with the climate crisis in a way that requires concerted goodwill tends to encourage cynicism and blame-shifting when countries fail to meet carbon emission reduction targets. The vast majority of countries are failing to lower emissions to levels that would keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius, as the 2015 Paris Agreement aspires to do. This collective failure dissipates blame and often disincentivizes countries from shouldering the burdens of emission reduction. Furthermore, focusing overtly on country-level climate reduction targets conceals the fact that emissions are largely generated by a handful of international corporations—over a third of all carbon and methane emissions since 1965 have been produced by 20 companies, including Saudi Aramco, Chevron, Exxon Mobil, and Royal Dutch Shell.

Holding corporations accountable for emissions requires immense political momentum, which is more easily galvanized by framing climate action as a necessary defense against immediate danger than as a voluntary restriction of certain economic activities for global well-being. While global cooperation to reduce emissions is what the international community should strive for, using nation-centered rhetoric that focuses on security threats can be an effective conduit to achieving this broader goal. Furthermore, linking the climate crisis to terrorism could increase the motivation and capital for countries to press hard in climate negotiations; in the face of immediate danger, the inertia of other countries or companies seems a paltry excuse for inaction.

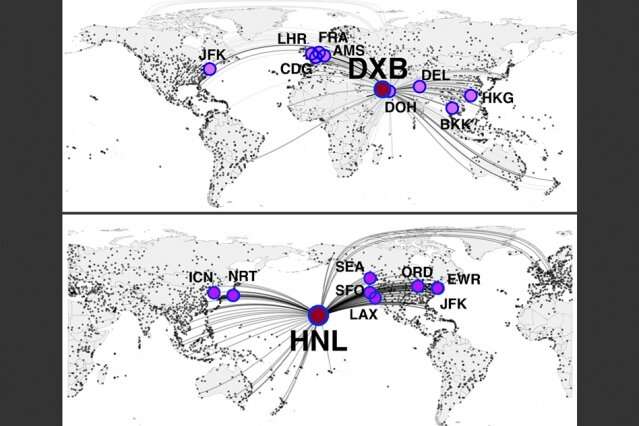

Based on their study, the authors found that focusing efforts to increase handwashing rates at just 10 airports chosen based on the location of the outbreak could significantly reduce disease spread. In these maps, they show the airports that would be targeted for outbreaks originating near Honolulu, Hawaii, or Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Credit: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Based on their study, the authors found that focusing efforts to increase handwashing rates at just 10 airports chosen based on the location of the outbreak could significantly reduce disease spread. In these maps, they show the airports that would be targeted for outbreaks originating near Honolulu, Hawaii, or Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Credit: Massachusetts Institute of Technology