Micron to cut 10% of workforce as demand for computer chips slumps

, Bloomberg News

Micron Technology Inc., the largest US maker of memory chips, gave a lackluster revenue outlook for the current period, indicating the slump in demand for computer components will drag on, and said it will reduce its workforce by about 10 per cent over the next year.

Sales will be about US$3.8 billion in the fiscal second quarter, Micron said Wednesday in a statement. That compares with analysts’ average estimate of US$3.88 billion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The company projected a loss of about 62 cents a share, excluding certain items, in the period ending in February, compared with a loss of 29 cents expected by analysts.

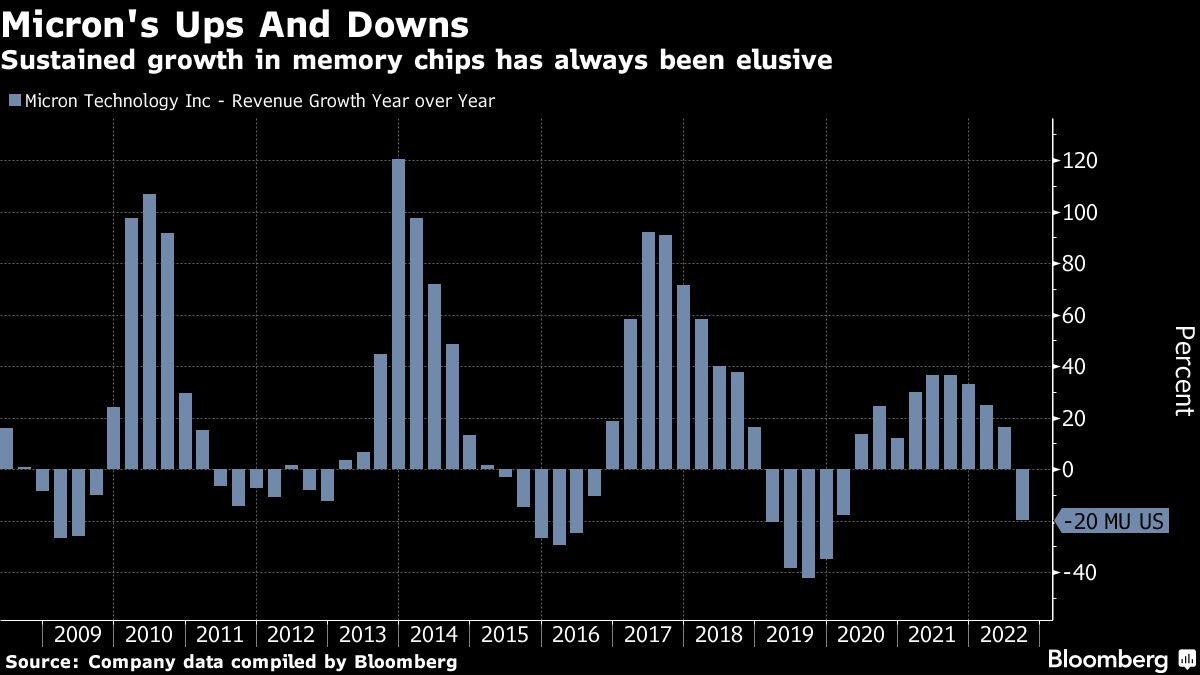

Semiconductor makers are suffering plummeting demand for their products less than a year after being unable to produce enough to meet orders. Consumers have shelved purchases of personal computers and smartphones amid rising inflation and an uncertain economy. Makers of those devices, the main users of memory chips, are now stuck with unused stockpiles of components and are slowing orders for new stock.

The industry is experiencing its worst imbalance between supply and demand in 13 years, according to Chief Executive Officer Sanjay Mehrotra. Inventory should peak in the current period, then decline the rest of the year, he said. Customers will move to more healthy inventory levels by about the middle of 2023, and the chipmaker’s revenue will improve in the second half of the year, Mehrotra said on a conference call after the results were released.

Micron is cutting its budget for new plants and equipment, and now expects to spend from US$7 billion to US$7.5 billion for the fiscal year, a reduction from an earlier target of as much as US$12 billion. The company is also slowing the introduction of more advanced manufacturing techniques. Micron predicts that overall industry spending on new production will also decline.

Unlike other parts of the chip sector, products from Micron are built to industry standards, meaning they can be swapped out for those of its competitors. Because memory can be traded like a commodity, its makers are exposed to more pronounced price swings.

Micron’s pledge to reduce output from its factories and slow expansion projects won’t ease the glut of chips available unless rivals, including Samsung Electronics Co. and SK Hynix Inc., follow suit. That step can help support prices but comes with the penalty of running expensive plants at less than full capacity, something that can weigh heavily on profitability.

It will be difficult to generate a profit in the memory chip industry in the coming year, Mehrotra said. In addition to its planned workforce reductions, the company has suspended share repurchases, is cutting executive salaries and will skip companywide bonus payments, executives said on the call.

In the three months ended Dec. 1, Micron’s sales declined 47 per cent to US$4.09 billion. The company had a loss of 4 cents a share, excluding certain items. That compares with an average estimate of a loss of 1 cent a share on revenue of US$4.13 billion.

Micron’s shares declined about 1.5 per cent in extended trading after closing at US$51.19 in New York. The stock has dropped 45 per cent this year, a worst decline than most chip-related equities. The Philadelphia Stock Exchange Semiconductor Index is down 33 per cent in 2022.

Last month the company warned it was cutting production by about 20 per cent “in response to market conditions.” Boise, Idaho-based Micron had 48,000 employees as of Sept. 1, according to filings.