Groundwater levels are sinking ever faster around the world

IMAGE:

GROUNDWATER-FED IRRIGATION BY AN ELECTRICITY-OPERATED PUMP IN SOUTHWESTERN BANGLADESH.

view moreCREDIT: PHOTOGRAPH: AHMED ZIAUR RAHMAN

At the beginning of November, The New York Times ran the headline, “America is using up its groundwater like there’s no tomorrow.” The journalists from the renowned media outlet had published an investigation into the state of groundwater reserves in the United States. They came to the conclusion that the United States is pumping out too much groundwater.

But the US isn’t an isolated case. “The rest of the world is also squandering groundwater like there’s no tomorrow,” says Hansjörg Seybold, Senior Scientist in the Department of Environmental Systems Science at ETH Zurich. He is coauthor of a study that has just been published in the journal Nature.

Scientific evidence of rapidly depleting water resources

Together with researchers from the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), he has corroborated the journalists’ worrying findings. It is not only in North America that far too much groundwater is being pumped out, but also in other parts of the world where humans have settled.

In an unprecedented feat of painstaking effort, the researchers have compiled and analysed data from over 170,000 groundwater monitoring wells and 1,700 groundwater systems over the past 40 years.

This measurement data shows that in recent decades, humans have massively expanded groundwater extraction worldwide. The water level in most groundwater-bearing rock layers, known as aquifers, has fallen drastically almost everywhere in the world since 1980. And since 2000, this decline in groundwater reserves has accelerated. The effects are most pronounced in aquifers in the world’s arid regions, including California and the High Plains in the US, along with Spain, Iran, and Australia.

“We weren’t surprised that groundwater levels have fallen sharply worldwide, but we were shocked at how the pace has picked up in the past two decades,” Seybold says.

One of the reasons Seybold cites for the accelerated drop in groundwater levels in arid regions is that people use these areas intensively for agriculture and are pumping (too) much of the groundwater to the surface to irrigate crops, for example in California’s Central Valley.

Food cultivation and climate change exacerbate the problem

Moreover, the world’s population is growing, which means more food needs to be produced, for example in the arid regions of Iran. This is one of the countries where groundwater reserves have fallen the most.

But climate change is also exacerbating the groundwater crisis: some areas have become drier and hotter in recent decades, meaning agricultural crops need to be irrigated more heavily. Where climate change is driving a decline in precipitation, groundwater resources recover more slowly, if at all.

Heavy rainfall, which is occurring more frequently in some places as a result of climate change, is also not of any help. If the water comes in huge quantities, the soil often cannot absorb it. Instead, the water drains off at the surface without seeping into the groundwater. This problem is particularly acute in places with a high level of soil sealing, such as large cities.

Trend can be reversed

“The study also reveals good news,” says co-author Debra Perrone. “Aquifers in some areas have recovered in places where there have been policy changes or where alternative sources of water are available for direct use or for recharging the aquifer.”

One of the positive examples is the Genevese aquifer, which supplies drinking water to around 700,000 people in the canton of Geneva and the neighbouring French department of Haute-Savoie. Between 1960 and 1970, its level fell drastically because both Switzerland and France were pumping out water in an uncoordinated manner. Some wells even dried up and had to be closed.

To preserve the shared water resource, politicians and authorities in both countries agreed to replenish the aquifer artificially with water from the Arve River. The intention was first to stabilise the groundwater level and later to raise it – and the intervention was a success. “While the water level in this aquifer may not have returned to its original level, the example shows that groundwater levels don’t always have to go only one way: down,” Seybold says.

Other countries are reacting, too

The authorities have also had to take action in other countries: In Spain, a large pipeline has been built to carry water from the Pyrenees to central Spain, where it feeds the Los Arenales aquifer. In Arizona, water is diverted from the Colorado River into other bodies of water to replenish the groundwater reservoirs – although this does cause the delta of the Colorado River to dry up at times.

“Such examples are a ray of hope,” says UCSB researcher and lead author Scott Jasechko. Nevertheless, he and his colleagues are urgently calling for more measures to combat the depletion of groundwater supplies. “Once heavily depleted, aquifers in semi-deserts and deserts may require hundreds of years to recover because there’s simply not enough rainfall to swiftly replenish these aquifers,” Jasechko says.

There is an additional danger on the coasts: if the groundwater level falls below a certain level, seawater can invade the aquifer. This salinises the wells, leaving the water that is pumped up unusable neither for drinking water nor for irrigating fields; trees whose roots reach into the flow of groundwater die. On the east coast of the US, there are already extensive ghost forests with not a single living tree.

“That’s why we can’t put the problem on the back burner,” Seybold says. “The world must take urgent action.”

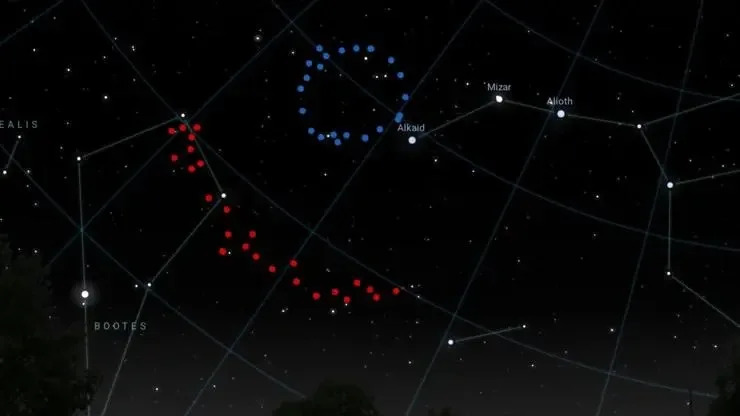

The world has a problem: On all inhabited continents, groundwater resources whose levels have fallen to various degrees are marked by light to dark red zones.

CREDIT

(Illustrations: Scott Jasechko, UCSB)

JOURNAL

Nature

ARTICLE TITLE

Rapid groundwater declines in many aquifers globally but cases of recovery

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

24-Jan-2024

Global groundwater depletion is accelerating, but is not inevitable

Aquifers are declining worldwide, put success stories highlight that proactive management can reverse these trends

IMAGE:

THIS PAPER PROVIDES THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE ACCOUNT YET OF TRENDS IN GROUNDWATER LEVELS AROUND THE WORLD. DARKER COLORS INDICATE CHANGES OF 10 CM/YEAR OR MORE.

view moreCREDIT: JASECHKO ET AL.

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — Groundwater is rapidly declining across the globe, often at accelerating rates. Writing in the journal Nature, UC Santa Barbara researchers present the largest assessment of groundwater levels around the world, spanning nearly 1,700 aquifers. In addition to raising the alarm over declining water resources, the work offers instructive examples of where things are going well, and how groundwater depletion can be solved. The study is a boon for scientists, policy makers and resource managers working to understand global groundwater dynamics.

“This study was driven by curiosity. We wanted to better understand the state of global groundwater by wrangling millions of groundwater level measurements,” said lead author Debra Perrone, an associate professor in UC Santa Barbara’s Environmental Studies Program.

The team compiled data from national and subnational records and the work of other agencies. The study took three years, two of which were spent just cleaning and sorting data. That’s what it takes to make sense of 300 million water level measurements from 1.5 million wells over the past 100 years.

Next came the task of translating the deluge of data into actual insights about global groundwater trends. The researchers then scoured over 1,200 publications to reconstruct aquifer boundaries in the regions of inquiry and evaluate groundwater level trends in 1,693 aquifers.

Their findings provide the most comprehensive analysis of global groundwater levels to date, and demonstrate the prevalence of groundwater depletion. The work revealed that groundwater is dropping in 71% of the aquifers. And this depletion is accelerating in many places: the rates of groundwater decline in the 1980s and ’90s sped up from 2000 to the present, highlighting how a bad problem became even worse. The accelerating declines are occurring in nearly three times as many places as they would expect by chance.

Groundwater deepening is more common in drier climates, with accelerated decline especially prevalent in arid and semi-arid lands under cultivation — “an intuitive finding,” said co-lead author Scott Jasechko, an associate professor in the university’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. “But it’s one thing for something to be intuitive. It’s quite another to show that it’s happening with real-world data.”

On the other hand, there are places where levels have stabilized or recovered. Groundwater declines of the 1980s and ’90s reversed in 16% of the aquifer systems the authors had historical data for. However, these cases are only half as common as would be expected by chance.

“This study shows that humans can turn things around with deliberate, concentrated efforts,” Jasechko said.

Take Tucson, Arizona for instance. Water allotted from the Colorado River is used to replenish the aquifer in the nearby Avra Valley. The project stores water for future use. “Groundwater is often viewed as a bank account for water,” Jasechko explained. “Intentionally refilling aquifers allows us to store that water until a time of need.”

Communities can spend a lot of money building infrastructure to hold water above ground. But if you have the right geology, you can store vast quantities of water underground, which is much cheaper, less disruptive and less dangerous. The stored groundwater can also benefit the region’s ecology. In fact, while preparing a research brief in 2014, Perrone found that aquifer recharge can store six times more water per dollar than surface reservoirs.

Tucson’s groundwater recharge is a boon for the local aquifer; however, withdrawals have caused the mighty river to dwindle above ground. The Colorado rarely reaches its delta in the California Gulf anymore. “These groundwater interventions can have tradeoffs,” Jasechko acknowledged.

Another option is to focus on reducing demand. Often this involves regulations, permitting and fees for groundwater use, Perrone explained. To this end, she is currently examining water law in the western U.S. to understand these diverse interventions. Regardless of whether it comes from supply or demand, aquifer recovery seemed to require intervention, the study revealed.

The authors complemented measurements from monitoring wells with data from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE). The GRACE mission consists of twin satellites that precisely measure the distance between them as they orbit the Earth. In this way, the crafts detect small fluctuations in the planet’s gravity, which can reveal the dynamics of aquifers at large scales.

“The beauty of GRACE is that it allows us to explore groundwater conditions where we don’t have in-situ data,” Perrone said. “Our assessment complements GRACE. Where we do have in-situ data, we can explore groundwater conditions locally, a crucial level of resolution when you’re managing depletion.” This local resolution is critical, as the authors found out, because adjacent aquifers can display different trends.

That said, groundwater level trends don’t present the whole picture. Even where aquifers remain stable, withdrawing groundwater can still affect nearby streams and surface water, causing them to leak into the subsurface, as Perrone and Jasechko detailed in another Nature paper in 2021.

The authors also analyzed precipitation variability over the past four decades for 542 aquifers. They found that 90% of aquifers where declines were accelerating are in places where conditions have gotten drier over the last 40 years. These trends have likely reduced groundwater recharge and increased demand. On the other hand, climate variability can also enable groundwater to rebound where conditions become wetter.

This study of monitoring wells complements a paper Perrone and Jasechko released in 2021. That study represented the largest assessment of global groundwater wells, and made the cover of the journal Science. “The monitoring wells are telling us information about supply. And the groundwater wells are telling us information about demand,” Perrone said.

“Taken together, they allow us to understand which wells have run dry already, or are most likely to run dry if groundwater-level declines occur,” Jasechko added.

Perrone and Jasechko are now examining how groundwater levels vary over time in the context of climate change. Connecting these rates of change to the depths of actual wells will provide better predictions of where groundwater access is at risk.

“Groundwater depletion is not inevitable,” Jasechko said. Fine resolution, global studies will enable scientists and officials to understand the dynamics of this hidden resource.

JOURNAL

Nature

ARTICLE TITLE

Rapid groundwater declines in many aquifers globally but cases of recovery

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

24-Jan-2024